A Vast Boneyard

by Diana Loski

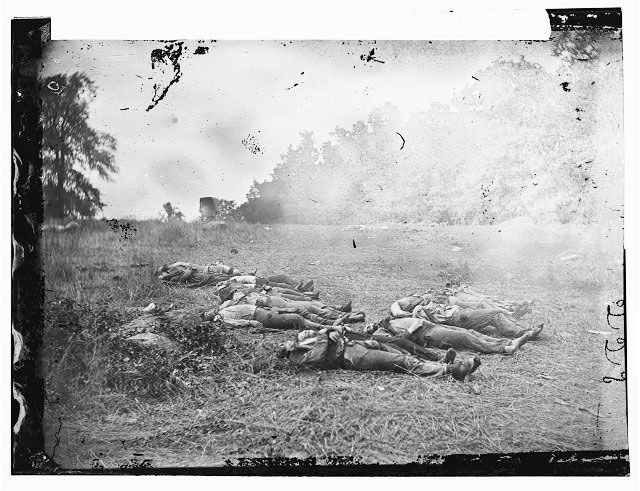

Some of the Confederate slain at Gettysburg

(Library of Congress)

In a letter to his parents on July 5, 1863, Henry M. Howells of the 124th New York wrote: “To-day there was a detail of two men from each company to bury the dead. I went, but I hope I may never have an opportunity to do so again.”1

So began the task of burying the dead and caring for the wounded – and many of the latter would not survive for long. While Lee’s army left on July 4 and the Union followed soon afterward, doctors, nurses, and civilian aid were desperately needed. Civilians rushed to Gettysburg, many to find their loved ones, many to lend their aid, and some out of curiosity. Their many descriptions paint a grisly picture of the vestiges of battle.

In a letter to his cousin, Edward Simmons from the First Maryland Eastern Shore Regiment remarked, “You have seen nothing of soldiering, nothing of the horrors of war….The horrid sights that meet the eye almost freeze the blood in one’s veins.”2

For many weeks, throughout the summer of 1863, Gettysburg was awash in the dead and the dying. The work of burying the myriad slain was the most compelling task at Gettysburg during the summer of 1863: “The enemy are whiped [sic] badly and are retreating, leaving their dead and wounded on the field for us to take care of. The field is filled with their dead. Whole crowds of men are at work burying them.”3

“It is heart-rending to pass through the streets and hear the cries and agony that burdens the air,” wrote a non-combatant Union soldier named Frank M. Stoke, who was ordered to remain as a guard for the Camp Letterman field hospital. “I have heard them when I was away from the hospital a half-mile.” He described a typical day at the camp hospital: “Those who die in the hospital are buried in the field south of [it]; there is a large graveyard there already. The dead are laid in rows with a rough board laced at the head of each man (nearly all are Confederates); the name of each man is written on the board…The amputated limbs are put into barrels and buried and left in the ground until they are decomposed, then lifted and sent to the Medical College at Washington. A great many bodies are embalmed here…Close to the graveyard is a tent called the dead house.”4

A Pennsylvania nurse, Emily Souder, arrived at Gettysburg on July 14th and described the scenes that shocked her: “The sights and the sounds are beyond description. There are hundreds of men who will never leave the battle-field alive and hundreds more who have ‘fought their last battle’. Dead men are being carried out to be buried every hour of the day.”5

“O, such piles of dead men and horses,” lamented a civilian who visited the battlefield with a journalist named George Washburn on the same day. “The whole plain beyond their battle line is one vast grave. ‘My God!’ says Washburn – ‘Lee must have sacrificed half his army here!’” 6

An Ohio clergyman who came to Gettysburg in mid-July observed: “Fences were gone, trees which had braved successive storms lifted their broken arms towards heaven to show what war can do. Crops were destroyed…wounded horses [were] wandering about, uncared for….On every hand were guns, canteens, shells, balls, and all the implements and accoutrements of the men who fought there so desperately a few days before. Crowds of people were driving and walking across that bloody plain, no fences to obstruct them…Indeed the whole field was horribly oppressive…Clots of blood, pieces of limbs of the poor men, and other horrible sights met the eye at every turn. Some of the rebel dead yet lie unburied.”7

The bloody plain was where much of the battle had transpired during July 2 and 3, 1863. It included the Pickett’s Charge field, as well as the areas west of the Round Tops: the Sherfy Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, the Slaughter Pen and the Valley of Death. It was over these fields that the majority of arrivals made their rounds.

Days after the battle, though, there were still wounded and dead on the fields of the First Day’s Battle, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, and as far south as East Cavalry Field. Many weeks passed before the dead could be buried and the wounded could be transported from all areas of the battlefield.

Since countless civilians continued to come to Gettysburg to search for their loved ones, many Gettysburg men offered to help in attempts to locate those who were buried, so that their families could retrieve the bodies. By late August, the exhumations were halted for a time, in order to keep the horrid stench of death at bay for the healing of the sick, and to devote time to the wounded who were still at the Camp Letterman field hospital. By early October, the exhumations were permitted to continue.8

In October, 1863, Private Frank M. Stoke had also returned. He wrote of aiding in the removal of bodies in late July into August: “When I was last here, the fields had the appearance of a vast boneyard. A few weeks ago the bodies became so decomposed that the heads would drop off the men – would drop from the slightest touch. Since then the heads have been kicked like footballs over the field.” He added that “the blankets that have been left on the fields are used to bear off the [dead] and are clotted with blood; many of the hats and caps are besmeared with brains.”9

At the time of the Soldiers National Cemetery dedication, on November 19, 1863 – a full month after Private Stoke’s last written description – the animal carcasses were still being burned and the stench of death still pervaded the town.

Nathaniel Lightner, whose farm was located near Culp’s Hill on the Baltimore Pike, had to move his family away from Gettysburg for nine years, as “such smells as came from the festering wounds, from the blood and medicine, stained floors and from the chloroform…became sickening…it made us all sick.”10

Sarah Broadhead, who lived near the Square on Chambersburg Street, lamented, “The atmosphere is loaded with the horrid smell of decaying horses and remains of slaughtered animals, and it is said, from the bodies of men imperfectly buried…every breath we draw is made ugly by the stench.”11

The hastily buried, shallow graves were later exhumed, but some who were buried more deeply remain on the ield. We will likely never know how many are still beneath the battlefield sod.

One who buried many of them remembered the grisly task for the remainder of his life: “As long as reason holds her sway, until all else is forgotten, I shall remember that day and its ghastly dead. We took them from perfect lines of battle as they had fallen; we dragged them out from behind rocks; we found them behind logs or lying over them, with eyes and mouths distended, and faces blackened with mortification. We found them everywhere in our front, from within a few feet of our fortifications to the foot of the hill.” 12

It is a ghastly remembrance indeed, and one we must never forget.

Sources: Baumgartner, Richard A. Buckeye Blood: Ohio at Gettysburg. Huntington, WVA: Blue Acorn Press, 2003. Broadhead, Sarah. Diary of a Lady. Copy, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Conklin, E.F. Women at Gettysburg 1863. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1993. Letter, Henry M. Howells to his Mother, 5 July, 1863, 124th New York File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Letter, Edw. Simmons, 1st MD Eastern Shore Reg’t to Dear Cousin Willie, 4 July 1863. Copy, GNMP. Lightner, Nathaniel. Civilian Account File, ACHS. Stoke, Frank M. “General Hospital” at Gettysburg, 26 Oct. 1863. Copy, Hospital File, GNMP.

End Notes:

1. Letter, Howells to his Mother, 5 July, 1863.

2. Letter, Simmons to Dear Cousin, 4 July, 1863.

3. Letter, Simmons to Dear Cousin, 4 July, 1863.

4. Stoke, 26 Oct. 1863. Private Stoke was a musician in Company F of the 1st PA Militia. He joined the army just before Gettysburg, in June 1863.

5. Conklin, p. 309.

6. Baumgartner, p. 184.

7. Ibid., p. 183.

8. Stoke, 26 Oct. 1863.

9. Ibid. Civilian laborers were hired to do the grisly work, as most Union soldiers were back to the front.

10. Lightner, Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

11. Broadhead, Diary of a Lad , ACHS.

12. Baumgartner, p. 174. The hill spoken of is Culp’s Hill.

Gettysburg, PA