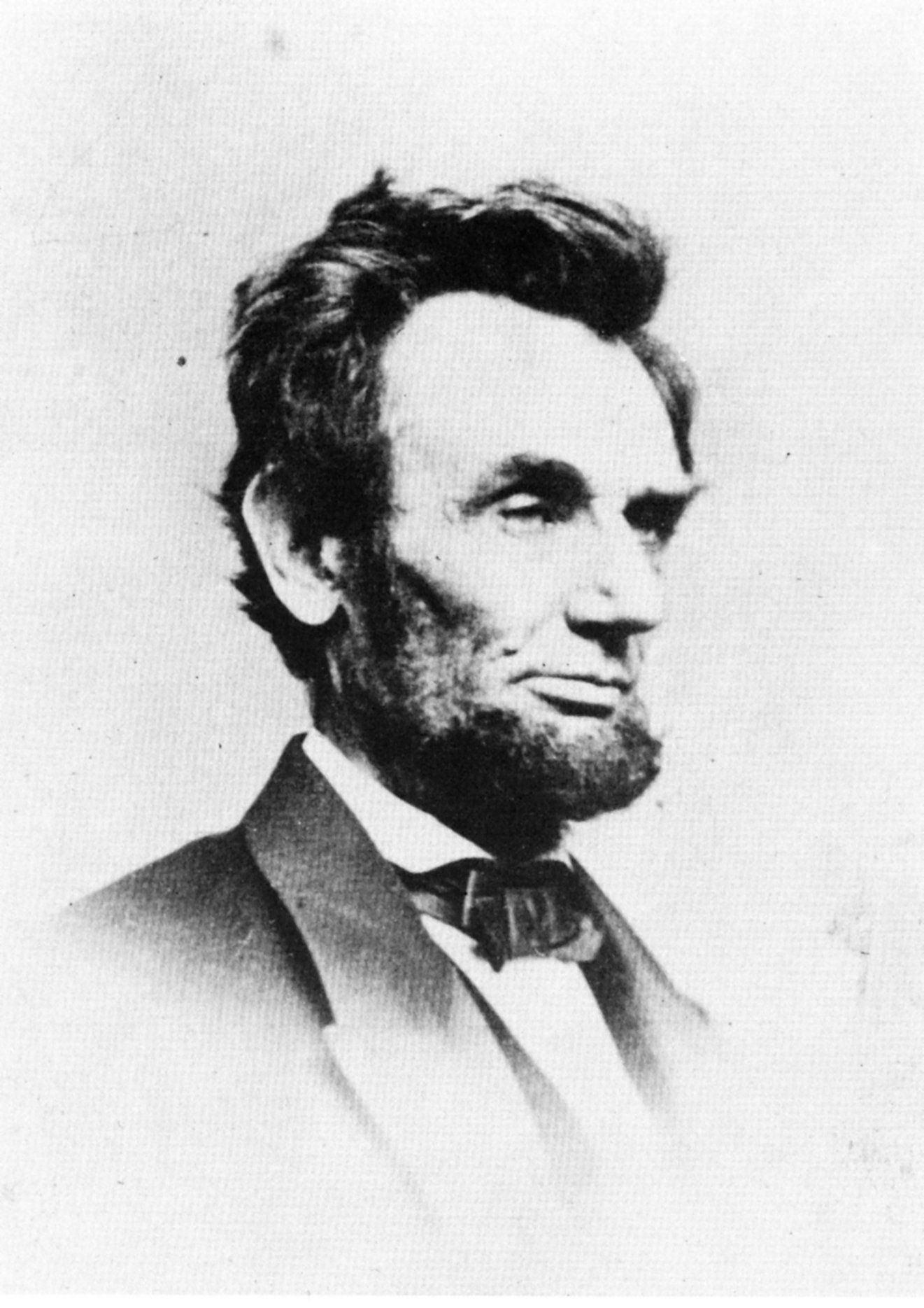

Abe Lincoln

(Library of Congress)

From sunset on a mild Wednesday evening through a sunny and temperate Thursday, on November 19, 1863, Gettysburg was a place of epic significance. Those scant hours, it could be said, changed the history of the world. During that day, a President came to Gettysburg for the simple reason that he had been invited there. His “few, appropriate remarks” that were given to dedicated the nation’s first national cemetery are still inspiring today. It could also be argued that, while the costly Battle of Gettysburg was the fight that saved the nation, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address cemented its salvation by galvanizing the citizen resolve to keep that nation, and that for which it stood, extant.1

Just two weeks and three days earlier, on November 2, Lincoln received a letter from Judge David Wills, a friend of Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin. Wills had determined that something permanent and dignified needed to be done for the thousands of Union slain from the Battle of Gettysburg earlier that summer. With the exorbitant cost of transferring thousands of mutilated bodies hundreds, even thousands, of miles away, most families could not afford to bring home their loved ones. Wills had seen to it that unused land adjacent to Evergreen Cemetery on Cemetery Hill was set aside to inter the dead heroes of the battle.

President Lincoln, realizing that he was not the keynote speaker – Edward Everett had already been secured long before Lincoln was invited – immediately accepted. For the next two weeks, he mused and wrote some of his thoughts on paper. When he boarded the train for Gettysburg on Wednesday, November 18, his remarks were not yet finished, but nevertheless had been ruminated and partially written.

Mary Lincoln had implored that her husband remain in Washington. Their youngest son, Tad, was ill with smallpox. After losing their beloved son, Willie, nineteen months earlier, Mary was understandably concerned. Lincoln, however, insisted upon his visit to Gettysburg. It was too important a request to ignore.

The train ride was long and tedious, and Lincoln did not arrive at the Gettysburg depot until about 7 p.m. Darkness had fallen, and large crowds had gathered around the station and the square, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Commander-in-Chief. David Wills had believed the widely circulated news reports that Lincoln was disliked and an embarrassment. The people who flocked to Gettysburg by the thousands proved him wrong. “The very mention of his name brings forth shouts and applause,” one Gettysburg resident claimed. “Such homage I never saw or imagined could be shown to any one person.”2

Judge Wills greeted the President and his sizable entourage, including members of his Cabinet and various dignitaries, at the station on Carlisle Street. He led them to his home in the center square – a handsome edifice that remains today. Lincoln, Everett, and Governor Curtin all stayed with David Wills and his wife, Jennie. Secretary of State William Henry Seward was housed next door. Because the town was overflowing with humanity, there were no spare rooms at any inns for the night. The judge encouraged Gettysburg residents to open their doors, and many did. One family housed the entire Baltimore Glee Club. Still, thousands roamed the town all night, unable to find a place to rest. Benjamin French, one of the contributors to the program for the dedication, lamented that the crowd continued cheering and singing late into the night, keeping him and many others from a night’s rest.3

Lincoln had barely settled into his room at the Wills house before the crowd clamored for him to appear. Not wishing to disappoint the people, Lincoln opened the York Street entrance door and stepped out. “Never did [a] mortal have a more enthusiastic greeting,” explained resident J. Howard Wert. “My eagerness to see and hear the President – whom I regarded above all other men, and second only to the Almighty – centered all my attention on Mr. Lincoln,” said Gettysburg youth and future photographer William Tipton, and “no word or movement of his escaped my attention.” He had expected a homely man, as Lincoln had so scurrilously been described by journalists and politicians of the day. Tipton thought otherwise. “When my eyes beheld that sad but kindly countenance,” he said, “those strong, rugged features seemed handsome to me.”4

Lincoln demurred from giving a speech, explaining that he preferred to save his words for tomorrow. He greeted the public until about 10 p.m., then withdrew to polish his speech.

A girl who lived a block away on York Street arrived at the Wills residence too late to see the President. In the dark, she stood outside in the square with her sisters. Liberty Hollinger finally caught a glimpse of Lincoln through the upstairs window. “We could distinctly see him pacing back and forth, in his room on the second story,” she said. “Twice he came to the window facing us as he looked out on the street, and each time he held in his hand a piece of yellow paper about the size of an ordinary envelope.”5

Eight-year-old Will Storrick had also not seen the President. As the darkness deepened in the center of town, he stood outside the Wills house listening to the bands. “I was delighted,” he remembered. “The music…was the best I had ever heard.”6

After working on the rest of his speech, Lincoln decided to consult his Secretary of State, William Seward, to review it. Although Judge Wills offered to fetch the Secretary, Lincoln insisted that he would go to Seward next door. When Lincoln and his bodyguard stepped into the street, the Storrick boy gazed up at him in amazement. “I was surprised, and I might say awed by his great height,” he remembered, “his black hair and beard, his dark complexion, his head covered in a stovepipe hat. I thought he was the tallest man I had ever seen.”7

After consulting with Seward, Lincoln returned to the Wills house and for much of the night remained awake, pacing the room and practicing his address for the following day. He received a telegram that his son, Tad, was improving, news that he was glad to receive. When Lincoln’s door closed for the remainder of the night, his bodyguard, Sergeant Hugh Paxton Bigham, took his place at the door.8

Thursday, November 19 dawned sunny and mild – unusual for mid-November in Pennsylvania. Lincoln emerged at 10 a.m. to take his place in the procession that led to the new Soldiers National Cemetery. The mare given to him for the occasion proved too small for his tall frame, but he accepted the horse with good humor. When they reached the new cemetery – still unfinished as all the dead had not yet been interred and the odor of death still permeated the county – Lincoln and the rest of the dignitaries took their place on the dais, with the exception of Edward Everett, who took solitude in a nearby tent. When he emerged, shortly before noon, the crowd in the cemetery was immense. It is believed at that least 15,000 people were present for the dedication. A funeral dirge played, and an invocation was delivered by Reverend Thomas H. Stockton, the Chaplain of the House of Representatives. His oration left many, including Lincoln, in tears.9

“The crowd was so dense,” said Gettysburg resident Robert McClean, “and the air rendered so close even on that day in late fall that more than one lady and even men fainted.”10

Edward Everett, notably the most popular speaker at the time, had gained national acclaim for his many speeches on George Washington. He spoke for two hours – a common practice at the time. He “had a sweet voice,” one listener remembered. “His eyes were piercing black, contrasting with his snow white hair,” recalled another. He finalized his oratory with the phrase: “All time is the millennium of their glory.” His Ciceronian skill was a marked contrast to Lincoln’s simple but eloquent speech that would follow.11

After Everett’s lengthy speech, the Baltimore Glee Club sang “The Consecration Hymn”, written by Benjamin French for the occasion. After the five-stanza hymn, Lincoln rose, his yellow paper in hand, his spectacles on his nose. He paused a moment before speaking. “He thrilled them by his very presence,” noted college student Henry Eyster Jacobs. “The stillness was very noticeable,” agreed another student named Philip Bikle.12

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, notably his greatest speech of many, explained the reason for the war and the necessity of dedicating the memory of the slain who strove to keep the nation of the people alive – and that the world was watching. His simple prose, mixed with the perfect amount of Biblical eloquence reached the crowd, who remained totally silent at his words. Finishing in just two minutes, Lincoln sat down, thinking the people did not care for his address. “Hill, ” he said to his friend Ward Hill Lamon, who served as Master of Ceremonies that day, “that speech won’t scour.”13

While partisan journalists excoriated his Gettysburg Address, the people who heard Lincoln that day most certainly appreciated his words. They took his speech to heart, and by their subsequent determination to see the war through, the “ government of the people” has continued to thrive. “The attention was just beginning to turn to the attention of the speaker,” explained William Tipton, “when he finished.” He added, “Mr. Lincoln’s sad face and the solemnity of the occasion seemed to forbid any excessive demonstration.” J. Howard Wert gave still another opinion: “Only a few really understood the greatness of the words then and there spoken.” The comprehension certainly came later.14

After the dedication ceremony, Lincoln attended a luncheon and greeted the public at a reception at the Wills house. Later that afternoon, he attended church, seated beside John Burns, the local constable who fought as a civilian at the Battle of Gettysburg. He also took a brief tour of the battlefield just west of town, and visited a sick lady, Carrie Sheads, at her bedside. She had worn herself out caring for the wounded of the battle.

When Lincoln boarded the train for Washington that evening around 6 p.m., he was not feeling well. A headache persisted and it appears he contracted a mild case of smallpox from his son, Tad. He had been in Gettysburg nearly twenty-four hours, but those hours constituted one of his greatest moments as President of the United States.

Before the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg, some of the most famous poets of the day, including William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and John Greenleaf Whittier, were approached and asked to create a poem for the occasion. They all declined. It all worked out for the best, however, as the immortal Gettysburg Address is the most poetic, the most sublime, the most celebrated utterance ever made by a President.

It was Lincoln who carried the day – and as a result, carried the nation.

Just two weeks and three days earlier, on November 2, Lincoln received a letter from Judge David Wills, a friend of Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin. Wills had determined that something permanent and dignified needed to be done for the thousands of Union slain from the Battle of Gettysburg earlier that summer. With the exorbitant cost of transferring thousands of mutilated bodies hundreds, even thousands, of miles away, most families could not afford to bring home their loved ones. Wills had seen to it that unused land adjacent to Evergreen Cemetery on Cemetery Hill was set aside to inter the dead heroes of the battle.

President Lincoln, realizing that he was not the keynote speaker – Edward Everett had already been secured long before Lincoln was invited – immediately accepted. For the next two weeks, he mused and wrote some of his thoughts on paper. When he boarded the train for Gettysburg on Wednesday, November 18, his remarks were not yet finished, but nevertheless had been ruminated and partially written.

Mary Lincoln had implored that her husband remain in Washington. Their youngest son, Tad, was ill with smallpox. After losing their beloved son, Willie, nineteen months earlier, Mary was understandably concerned. Lincoln, however, insisted upon his visit to Gettysburg. It was too important a request to ignore.

The train ride was long and tedious, and Lincoln did not arrive at the Gettysburg depot until about 7 p.m. Darkness had fallen, and large crowds had gathered around the station and the square, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Commander-in-Chief. David Wills had believed the widely circulated news reports that Lincoln was disliked and an embarrassment. The people who flocked to Gettysburg by the thousands proved him wrong. “The very mention of his name brings forth shouts and applause,” one Gettysburg resident claimed. “Such homage I never saw or imagined could be shown to any one person.”2

Judge Wills greeted the President and his sizable entourage, including members of his Cabinet and various dignitaries, at the station on Carlisle Street. He led them to his home in the center square – a handsome edifice that remains today. Lincoln, Everett, and Governor Curtin all stayed with David Wills and his wife, Jennie. Secretary of State William Henry Seward was housed next door. Because the town was overflowing with humanity, there were no spare rooms at any inns for the night. The judge encouraged Gettysburg residents to open their doors, and many did. One family housed the entire Baltimore Glee Club. Still, thousands roamed the town all night, unable to find a place to rest. Benjamin French, one of the contributors to the program for the dedication, lamented that the crowd continued cheering and singing late into the night, keeping him and many others from a night’s rest.3

Lincoln had barely settled into his room at the Wills house before the crowd clamored for him to appear. Not wishing to disappoint the people, Lincoln opened the York Street entrance door and stepped out. “Never did [a] mortal have a more enthusiastic greeting,” explained resident J. Howard Wert. “My eagerness to see and hear the President – whom I regarded above all other men, and second only to the Almighty – centered all my attention on Mr. Lincoln,” said Gettysburg youth and future photographer William Tipton, and “no word or movement of his escaped my attention.” He had expected a homely man, as Lincoln had so scurrilously been described by journalists and politicians of the day. Tipton thought otherwise. “When my eyes beheld that sad but kindly countenance,” he said, “those strong, rugged features seemed handsome to me.”4

Lincoln demurred from giving a speech, explaining that he preferred to save his words for tomorrow. He greeted the public until about 10 p.m., then withdrew to polish his speech.

A girl who lived a block away on York Street arrived at the Wills residence too late to see the President. In the dark, she stood outside in the square with her sisters. Liberty Hollinger finally caught a glimpse of Lincoln through the upstairs window. “We could distinctly see him pacing back and forth, in his room on the second story,” she said. “Twice he came to the window facing us as he looked out on the street, and each time he held in his hand a piece of yellow paper about the size of an ordinary envelope.”5

Eight-year-old Will Storrick had also not seen the President. As the darkness deepened in the center of town, he stood outside the Wills house listening to the bands. “I was delighted,” he remembered. “The music…was the best I had ever heard.”6

After working on the rest of his speech, Lincoln decided to consult his Secretary of State, William Seward, to review it. Although Judge Wills offered to fetch the Secretary, Lincoln insisted that he would go to Seward next door. When Lincoln and his bodyguard stepped into the street, the Storrick boy gazed up at him in amazement. “I was surprised, and I might say awed by his great height,” he remembered, “his black hair and beard, his dark complexion, his head covered in a stovepipe hat. I thought he was the tallest man I had ever seen.”7

After consulting with Seward, Lincoln returned to the Wills house and for much of the night remained awake, pacing the room and practicing his address for the following day. He received a telegram that his son, Tad, was improving, news that he was glad to receive. When Lincoln’s door closed for the remainder of the night, his bodyguard, Sergeant Hugh Paxton Bigham, took his place at the door.8

Thursday, November 19 dawned sunny and mild – unusual for mid-November in Pennsylvania. Lincoln emerged at 10 a.m. to take his place in the procession that led to the new Soldiers National Cemetery. The mare given to him for the occasion proved too small for his tall frame, but he accepted the horse with good humor. When they reached the new cemetery – still unfinished as all the dead had not yet been interred and the odor of death still permeated the county – Lincoln and the rest of the dignitaries took their place on the dais, with the exception of Edward Everett, who took solitude in a nearby tent. When he emerged, shortly before noon, the crowd in the cemetery was immense. It is believed at that least 15,000 people were present for the dedication. A funeral dirge played, and an invocation was delivered by Reverend Thomas H. Stockton, the Chaplain of the House of Representatives. His oration left many, including Lincoln, in tears.9

“The crowd was so dense,” said Gettysburg resident Robert McClean, “and the air rendered so close even on that day in late fall that more than one lady and even men fainted.”10

Edward Everett, notably the most popular speaker at the time, had gained national acclaim for his many speeches on George Washington. He spoke for two hours – a common practice at the time. He “had a sweet voice,” one listener remembered. “His eyes were piercing black, contrasting with his snow white hair,” recalled another. He finalized his oratory with the phrase: “All time is the millennium of their glory.” His Ciceronian skill was a marked contrast to Lincoln’s simple but eloquent speech that would follow.11

After Everett’s lengthy speech, the Baltimore Glee Club sang “The Consecration Hymn”, written by Benjamin French for the occasion. After the five-stanza hymn, Lincoln rose, his yellow paper in hand, his spectacles on his nose. He paused a moment before speaking. “He thrilled them by his very presence,” noted college student Henry Eyster Jacobs. “The stillness was very noticeable,” agreed another student named Philip Bikle.12

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, notably his greatest speech of many, explained the reason for the war and the necessity of dedicating the memory of the slain who strove to keep the nation of the people alive – and that the world was watching. His simple prose, mixed with the perfect amount of Biblical eloquence reached the crowd, who remained totally silent at his words. Finishing in just two minutes, Lincoln sat down, thinking the people did not care for his address. “Hill, ” he said to his friend Ward Hill Lamon, who served as Master of Ceremonies that day, “that speech won’t scour.”13

While partisan journalists excoriated his Gettysburg Address, the people who heard Lincoln that day most certainly appreciated his words. They took his speech to heart, and by their subsequent determination to see the war through, the “ government of the people” has continued to thrive. “The attention was just beginning to turn to the attention of the speaker,” explained William Tipton, “when he finished.” He added, “Mr. Lincoln’s sad face and the solemnity of the occasion seemed to forbid any excessive demonstration.” J. Howard Wert gave still another opinion: “Only a few really understood the greatness of the words then and there spoken.” The comprehension certainly came later.14

After the dedication ceremony, Lincoln attended a luncheon and greeted the public at a reception at the Wills house. Later that afternoon, he attended church, seated beside John Burns, the local constable who fought as a civilian at the Battle of Gettysburg. He also took a brief tour of the battlefield just west of town, and visited a sick lady, Carrie Sheads, at her bedside. She had worn herself out caring for the wounded of the battle.

When Lincoln boarded the train for Washington that evening around 6 p.m., he was not feeling well. A headache persisted and it appears he contracted a mild case of smallpox from his son, Tad. He had been in Gettysburg nearly twenty-four hours, but those hours constituted one of his greatest moments as President of the United States.

Before the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg, some of the most famous poets of the day, including William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and John Greenleaf Whittier, were approached and asked to create a poem for the occasion. They all declined. It all worked out for the best, however, as the immortal Gettysburg Address is the most poetic, the most sublime, the most celebrated utterance ever made by a President.

It was Lincoln who carried the day – and as a result, carried the nation.