Remembering the Great Emancipator

by Diana Loski

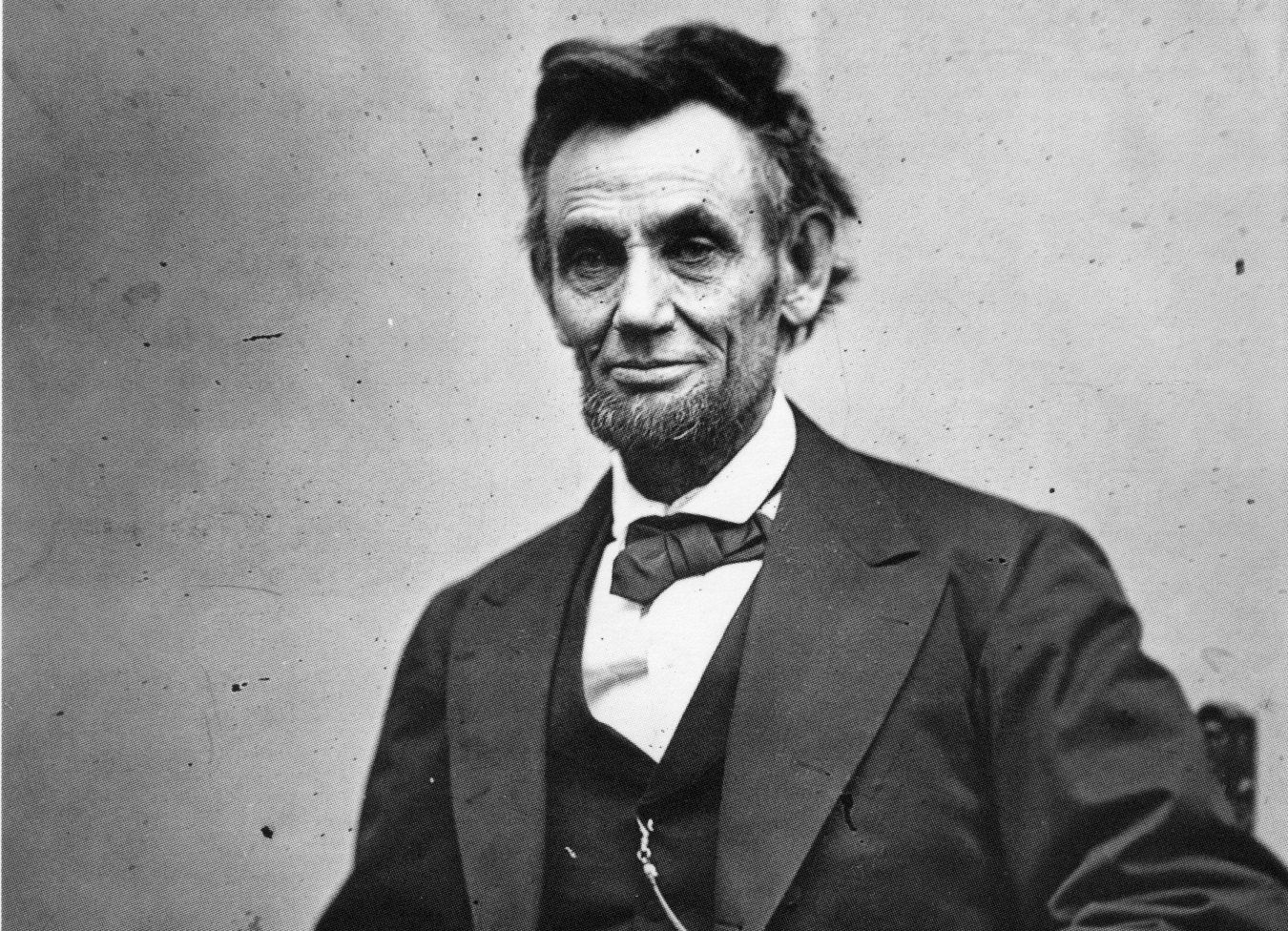

(Library of Congress)

In the latter part of September, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln announced a promise to issue a proclamation to free the slaves in the South. Called Proclamation 95, the document, an Executive Order, is also known to history as The Emancipation Proclamation. In the five-page document, preserved in the National Archives, the 16th President avers that “all persons held as slaves within any state or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall be in rebellion against the United States, shall be, then, thenceforward, and forever free.”1

Lincoln had long detested the institution of slavery. As a young man, he was employed in taking merchandise south to sell in New Orleans from his home in New Salem, Illinois. Lincoln’s cousin, John Hanks, accompanied him on his first voyage to Louisiana on the Mississippi River. Hanks recalled, “We saw negroes in chains – whipped and scourged…and his sense of right and justice rebelled. The whole thing was so revolting that Lincoln moved away from the scene with deep feeling of unconquerable hate….[he said] ‘By God, boys let’s get away from this. If ever I get a chance to hit that thing (meaning slavery), I’ll hit it hard.'”2

His stance never waned, and his public debates about it made him a national figure. When he was elected President of a divisive United States, eleven states seceded, refusing to acknowledge him as their President. Their rebellion soon led to civil war.

As the war continued through the sweltering summer of 1862, Lincoln met with his Cabinet to think of a way to bring the conflict to an end. He believed that the border states, which still swore allegiance to the Union, and yet remained slave states (Kentucky, Missouri, Delaware, and Maryland), would likely “surrender on fair terms their own interest in Slavery rather than see the Union dissolved.” His cabinet disagreed, arguing that any form of emancipation “would further consolidate the spirit of rebellion” and lengthen the war.3

The Army of the Potomac had recently withdrawn from the Peninsula Campaign in July, rendering rather bleak any hope for a Union victory and end to the war. Lincoln knew they needed to “change our tactics,” he recalled, “or lose the game.” He knew emancipation was the answer – something he had wanted all along.4

Lincoln’s Cabinet was not agreeable to the idea. “It may be viewed as the last measure of an exhausted government,” Secretary of State Seward opined, “a cry for help.” The Secretary suggested that the proclamation be given after a Union victory. Lincoln agreed. With the Union win at Antietam two months later, Lincoln had his moment, and he finished his second draft of the document shortly afterward. He then sent it to Congress to get their views.5

The Republican Congress was mostly in agreement with the President. They recognized the constitutionality of the abolishment of the institution. However, Lincoln met opposition when he insisted that only the slaves from the Confederate states qualified at that time. The abolitionist members of Congress wanted all slaves freed. Lincoln, though, in discussions with his trusted Cabinet, realized that he did not want to antagonize the Union states where its citizens owned slaves -- perhaps forcing an issue that might tip the balance, losing those allies to the Confederacy. Lincoln, ever the advocate for freedom for all, understood that even though slavery was morally wrong, he could not ignore any Constitutional protection where, in the Union states, the institution was protected and was unfortunately still lawful. He wrestled with the answer to this difficult situation.6

On September 22, Lincoln made public his intention to free the slaves of the Confederate States, and that it would be effective on January 1, 1863.

The November elections in the fall of 1862 saw a surge in Democratic statesmen to Congress, causing chaos in the nation’s capital. “I have done things lately that must be incomprehensible to the people,” Lincoln acknowledged. He nevertheless stood firm – though many thought he would not sign the proclamation as he had promised.7

In December, more disaster for the Union occurred at the Battle of Fredericksburg. On New Year’s Eve, another terrible battle ensued in Tennessee, between William Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland, and Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. It finally resulted in a Union victory, but on New Year’s Day, Lincoln would not have known it.

On January 1, there was a New Year’s Day reception at the Executive Mansion in the morning. Diplomats and national statesmen, as well as high officers of the military were in attendance. Lincoln greeted and shook hands for three hours.

Then, in the afternoon, as promised, Lincoln assembled his Cabinet and spread the historic document before him. The Emancipation Proclamation still needed his signature to be a lawful executive order. “I have never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper,” Lincoln said. “But I have been receiving calls and shaking hands since nine o’clock this morning, till my arm is stiff and numb. Now this signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled they will say, ‘he had some compunctions,’ but anyway, it is going to be done.”8

And he slowly and deliberately signed the document.

With the signature of the Emancipation Proclamation, the United States government also allowed former slaves to volunteer for military service. Near the end of the proclamation, Lincoln had declared, “And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind.”9

The Emancipation Proclamation did arouse some opposition from men in power in the border states, as was expected. In 1864, the Governor of Kentucky, Albert G. Hodges, wrote to Lincoln about the President’s stance against slavery, insisting that it evoked some harsh criticism from his state. Lincoln replied, “I am naturally against slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not [sic] remember when I did not so think and feel.”10

Lincoln was, as usual, correct.

Knowing that his proclamation was only as valid as he remained in office, Lincoln worked tirelessly in January 1865 to get Congress to pass a more enduring Constitutional law. The 13th Amendment, which was ratified after Lincoln’s death in December 1865, states that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”11

Since Gettysburg and Abraham Lincoln share a special historical bond, it is appropriate that, on the grounds of Gettysburg College a statue has been erected, entitled The Great Emancipator. It depicts the 16th President seated, in deep thought, with the famous proclamation in his lap. With pen in hand, he is preparing the sign the document that will proclaim all Americans “forever free.”

Though he paid for his determination to free the slaves with his own life, his legacy as The Great Emancipator will certainly live on for generations to come.

Sources: The Constitution of the United States. Philadelphia, PA: The National Constitution Center, July 4, 2003. The Emancipation Proclamation, National Archives, Washington, D.C., archives.gov. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Herndon, Willian H. and Jesse W. Weik. Herndon’s Lincoln. Urbana and Chicago: Knox College Lincoln Studies Center, the University of Illinois Press, 2006 (reprint, first published in 1889). Letter, Abraham Lincoln to the Hon. Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864. Abrahamlincolnonline.org. Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. New York: Galahad Books, 1993 (first published as two volumes, 1925 and 1936, respectively).

End Notes:

1. The Emancipation Proclamation, archives.gov.

2. Herndon, p. 60.

3. Goodwin, p. 459.

4. Sandburg, p. 319.

5. Ibid.

6. Goodwin, p. 462.

7. Sandburg, p. 325.

8. Ibid. p. 344.

9. The Emancipation Proclamation, archives.gov.

10. Letter, Abraham Lincoln to Hon. Albert G. Hodges, abrahamlincolnonline.org.

11. The Constitution of the United States, p. 25.