General G.K. Warren: His Finest Hour

by Diana Loski

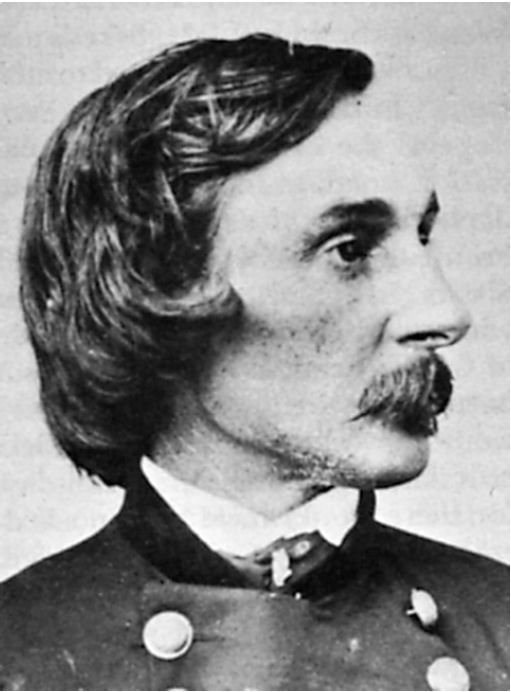

Brig. Gen. G.K. Warren (detail)

(Library of Congress)

The late afternoon of July 2, 1863 was hot, made worse by the crushing humanity in woolen uniforms, wearing blue and gray. Scanning the Emmitsburg Road, about a half-mile to the front of the Union deployment at Gettysburg, a slight but stalwart officer wearing the blue noticed a phalanx of Federal troops far to the front. They were the Union Third Corps, and the general knew they weren’t supposed to be there. Deciding to check the entire Union line, the officer was aghast to find that Little Round Top, the anchor to the Union left flank, was devoid of fighting troops. He noticed that men in gray – the Confederates – were already progressing toward the spot. Noticing among the bursting shells and crackle of musketry a brigade in blue advancing below the hill, the officer quickly rode after it.

What followed would prove a turning point for the battle and the war.

Gouverneur Kemble Warren was born to be a soldier. The fourth of twelve children, he came into the world on January 8, 1830. Warren grew up just across the Hudson River from West Point Military Academy. He was, in fact, named for a Congressman and close friend of his father, named Gouverneur Kemble – a diplomat who established an iron works foundry for artillery in the area. The namesake youth followed in Kemble’s footsteps with a penchant for all things military, and was accepted to West Point at the age of 16. He graduated near the top of his class in 1850, as a lieutenant in the topical engineers.1

While Warren was in some perilous skirmishes on the frontier, his talents lay in engineering. Under Captain A.A. Humphreys, Warren worked as a surveyor of the Mississippi River, and other rivers of the area, including in the Dakota and Nebraska Territories. In 1859, he was sent east to teach mathematics at West Point, a post he held until war erupted in 1861.2

Warren quickly offered his services to the Union, and was assigned as the Lieutenant Colonel of the 5th New York Regiment, also known as Duryea’s Zouaves. Warren was the first West Point officer to join a volunteer regiment of the Civil War.3

The 5th New York became embroiled in their first battle at Big Bethel on June 10, 1861 – a fight that the Union lost. Though Warren was quiet, slender and scholarly, he was also fearless in battle and given to fits of profanity when angered. These traits endeared him to the men, who affectionately called him “Gouv”. According to one who served with him, Warren “revealed those traits of coolness and good judgment which were conspicuous elements of his nature.” Still another remarked that Warren’s “large, expressive eyes could beam in tenderness or flash with the wild light of conflict.”4

The 5th New York was transferred in the summer of 1861 to Baltimore, to increase fortifications there. While there, Colonel Duryea was promoted, and Warren commanded the regiment. Warren also became acquainted with a beautiful local citizen named Emily Chase.5

The Warren statue, Little Round Top

(Author photo)

In the spring of 1862, Warren and his regiment were dispatched to the Army of the Potomac under General McClellan. They fought at the Battles of Yorktown and Williamsburg. After the siege at Yorktown, Warren was promoted to brigade command. He was wounded soon after, at the Battle of Gaines Mill, a knee injury. Though painful, the wound was not serious, and Warren quickly returned to the fighting. He fought at 2nd Manassas, but was held in reserve at Antietam in September 1862. He watched in despair as his compatriots were cut down.

Another disaster for the Union came with the Battle of Fredericksburg in December. Warren’s brigade formed the rear guard at that battle. The young general was the last man in Union blue to cross the Rappahannock at the battle’s end.6

Warren was concerned, not just because of the Union losses, but the occupational hazards within the army – every bit as dangerous as flying lead and men in gray. Both McClellan and Burnside were relieved of their commands. A friend to both, Warren was disgusted at their removal. When Joe Hooker replaced Burnside in early 1863, Warren was surprised that Hooker asked the young New Yorker to serve on his staff as one of two Chief Engineers. Hooker whipped the army into shape, skillfully improving the cavalry, feeding the men better rations, cleaning up the fetid camps, and improving morale. Hooker saw genius in Gouverneur Warren, and realized that Warren’s intelligence would best be used in topographical engineering.7

Like his predecessors, Hooker was better at organization than fighting Robert E. Lee. Marching back toward Fredericksburg, Hooker split Lee’s army near the forests of Chancellorsville, and then lost his nerve. In the ensuing battle, Lee managed to undo the division and soundly beat Hooker and his army. The Battle of Chancellorsville is known to history as Lee’s greatest victory. He achieved it, though, with heavy losses, including one of his trusted lieutenant generals, Thomas J. Jackson.

After retreating from Chancellorsville, the Union forces remained in Northern Virginia in an attempt to protect Washington from the Confederates. Lee’s army was soon on the move northward. Hooker and the Army of the Potomac followed, keeping watch over Lee and his men. During this interlude, Gouverneur Warren was given leave. He hurried to Baltimore, where he married Emily Chase, on June 17, 1863.8

Warren had only enjoyed one day with his new wife when he was called back to service. A new general took over the Army of the Potomac, the capable George Meade. Lee’s army had marched into Maryland, and the fact that the two armies would soon clash was inevitable.

Warren had served on the staff of General Hooker, and remained the Chief Engineer with General George Meade. Battle was imminent, and General Meade had no time to prepare a new staff. As Lee’s men entered Pennsylvania, Meade, with Warren at his side, scouted territory in a rural area in northern Maryland known as the Pipe Creek region. Meade hoped to lure Lee into battle there. Fate, however, intervened, and portions of the two armies clashed on July 1 at Gettysburg.

It was Warren who rushed to Gettysburg to confer with General Winfield S. Hancock, who had taken temporary command after the equally temporary Union defeat. Warren approved of Hancock’s battle line – in the shape of a fishhook, with its flanks well entrenched on hills – Little Round Top on the left and Culp’s and Cemetery Hills on the right.

By the next day, July 2, most of the Union troops had arrived, or were reaching Gettysburg. Not all of Lee’s troops had arrived by the afternoon – which prompted Union Third Corps commander Dan Sickles to decide he didn’t like his position to the left of Cemetery Ridge and moved his entire corps away from the main line, most of them to the Emmitsburg Road.

The makings of a disaster were easily seen by those who understood the importance of high ground. Warren noticed Sickles’ troops far from the rest of the Union line, and quickly wrote a note to General Meade.

On Seminary Ridge opposite the Union deployment, General Longstreet, Lee’s second in command, also noticed the errant Union Third Corps. Waiting for the rest of his troops to arrive before attacking the Union flanks – he saw the opportunity and immediately sent in his men to take Little Round Top.

General Warren noticed the movement, his mathematical mind giving in to mounting concern. Devil’s Den, five hundred yards to the west, was already engaged, and the Wheatfield behind it was also hotly contested. Fearing that replacements would come too late, Warren noticed a Union brigade below him, marching toward the Wheatfield in the distance. He recognized the commander at the head one of the regiments. It was one of his former pupils at West Point, Colonel Patrick O’Rorke.

Warren galloped to meet the troops. “Paddy, Paddy!” he shouted. “Give me a regiment!” O’Rorke stopped, and replied, “General Weed wishes that I follow him.” “Never mind that,” Warren insisted. “Bring your regiment up here, and I will take the responsibility.”9

O’Rorke complied, and quickly placed his 140th New York at the summit of Little Round Top. Warren had also dispatched one of his orderlies, who relayed the urgency to Colonel Strong Vincent, a brigade commander. Vincent immediately saw the danger and deployed his entire brigade on the southern edge of the hill. Soon General Weed also placed the rest of his brigade on Little Round Top. The Union troops occupied the hill just minutes before the Alabama troops from Evander Law’s brigade reached it. A terrible fight ensued, where O’Rorke was killed and Weed and Vincent were mortally wounded. Warren too, was shot in the neck – a non-fatal wound, but one that still bothered him immensely.

But Little Round Top held. Warren’s quick thinking with the immediate deployment of the two brigades had saved the Union position.

That evening, General Meade, new to command of the entire army, decided to hold a council of war at his headquarters on Cemetery Ridge. The collection of corps commanders and staff all agreed to stay and fight another day at Gettysburg. Warren, exhausted from the occurrences of the day, slumped into a corner, his wound still bleeding, and slept.10

The Battle of Gettysburg did last one more day, and with the Union victory over the Culp’s Hill battle that morning and Pickett’s Charge that afternoon, a Federal victory was secured.

The war, however, continued as the Confederates hoped to outlast the Lincoln administration. The year 1864 was a difficult one, a dark time with never ending casualties. General Ulysses S. Grant, the recent victor from the siege at Vicksburg, was promoted to commander of all Union armies early that year. Deciding that Lee was the man to conquer, Grant decided to fight with the Army of the Potomac. General Meade remained commander of the army, but answered to Grant, his superior officer.

Warren did not care for the generals from the west, and unfortunately for him, voiced that opinion. His criticisms of Grant and Philip Sheridan – Grant’s cavalry commander – reached their ears. Sheridan, an intense fighter, was also critical, and he hated easily. His hatred for Warren was only outdone by his hatred for any man wearing gray.11

Warren was put in temporary command of the Federal Second Corps, after the wounding of General Hancock at Gettysburg. In the spring of 1864, he was put in permanent command of the Union Fifth Corps. He fought in the major battles of 1864, and was actively engaged at the Siege of Petersburg, often leading his troops in skirmishes around the city.

When Lincoln won reelection in November that year, the days of the Confederacy were dwindling. By the spring of 1865, Lee’s army was in tatters, severely malnourished, and hopelessly outnumbered. Realizing that Petersburg would soon fall, Lee began to remove his troops from the city in an attempt to join Joe Johnston’s army in North Carolina.

Petersburg officially fell to the Union on April 2, 1865. The day before, however, the Union met the retiring Confederates at a significant fork in the road south of Petersburg, known as Five Forks. Sheridan had ordered Warren to bring his troops to the front, and Warren complied. Due to the bucolic nature of the area, with dense forest, Warren noticed that his men were placed too far to the right of the area of conflict. He corrected the error and led his troops in a subsequent charge that secured a Union victory. Warren’s exhilaration, though, was quickly dashed when Sheridan promptly relieved him from command.

Warren disputed the charges, but Sheridan would not relent. Sheridan wrote, among other things that Warren “did not exert himself” at the battle and “failed to reach me…when I expected him.” The allegations were petty to be sure, but Grant sided with Sheridan and Warren remained relieved of his command. To make matters worse, after the war Grant was elected President of the United States. Warren requested an inquiry multiple times, but as long as Grant was the Chief Executive, Warren’s hopes for exoneration were not realized. Finally, in 1879, with Rutherford Hayes as President, Warren was able to defend himself with an inquiry. As with most governmental jurisprudence, even military ones, the process was a long one. The terrible debacle left Warren understandably bitter.12

After the war, General Warren moved with his wife, Emily, and their three children to the East Coast, where the scholarly engineer was still in demand. He lived the last years of his life in Newport, Rhode Island, as an engineer for the United States in coastal fortifications for most of New England. He died on August 8, 1882 “after an illness lasting but a few days” at his home. He was fifty-two years old. Although the court of inquiry finally exonerated him from the malicious accusations of his nemesis, Phil Sheridan, the fallout from the scandal had tarnished his reputation – and at Warren’s death, the decision had still not been finalized. The emotional toll had affected Warren physically.13

The state of Warren’s mind was made evident at his funeral in Newport on August 12, 1882. While numerous generals and veterans of the late war attended, Warren had expressly demanded that “the funeral was purely a civic one.” He wore no uniform for his last appearance, and no military fanfare accompanied his final journey.14

At Gettysburg, a just tribute was given to the man who helped save Little Round Top. Six years after his death – to the day – on August 8, 1888, a portrait statue of Gouverneur Warren was dedicated at the summit of the hill he had discovered without the needed troops so many years before. The slender, slight commander gazes out over the field below, just as Warren had done at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863.15

There are many heroes at Gettysburg, North and South, and many heroes of Little Round Top. Warren was one of those heroes, and it was he who put the other Union heroes on that hill to secure the position. It was an act that procured a victory for the Union and, eventually, proved the turning point of the war.

Gettysburg was Warren’s finest hour – and the remembrance in his likeness remains a fitting elegy for the man, born across the Hudson from West Point, who had only wanted to be a soldier.

Sources: Appleton, John, Ed. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. VI. New York: Appleton and Sons, 1889. Lyon, J.B. and Company. New York at Gettysburg. Vol. 3, New York: 1902. The Fall River Herald, Fall River, Massachusetts, August 12, 1882. Gerrish, Theodore. Army Life: A Private’s Reminiscences of the Civil War. Gettysburg, PA: Stan Clark Military Books, 1995 (reprint). Hawthorne, Frederick W. Gettysburg: The Story of Men and Monuments. Hanover, PA: The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides/ printed by Sheridan Press, 1988. Newport Mercury and Weekly News, Newport, Rhode Island, August 12, 1882. Norton, Oliver Willcox. The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top. Gettysburg, PA: Stan Clark Military Books, 1992 (reprint). Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: The Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge and London: The Louisiana State University Press, 1996 (reprint, first published in 1964). Historical newspapers found at newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Warner, p. 541. Newport Mercury & Daily News, p. 1.

2. Appleton, p. 390.

3. Newport Mercury & Daily News, p. 1.

4. New York at Gettysburg, p. 981. Gerrish, p. 342.

5. Appleton, p. 390.

6. New York at Gettysburg, p. 981.

7. Ibid.

8. Appleton, p. 390.

9. Norton, p. 130.

10. Ibid.

11. New York at Gettysburg, p. 981. Sheridan had been suspended from West Point for a year due to his cantankerous nature and frequent fighting with other cadets.

12. Appleton, p. 391. Newport Mercury & Daily News, p. 1. Warner, p. 542.

13. Newport Mercury & Daily News, p. 1.

14. Fall River Daily, p. 1.

15. Hawthorne, p. 56.