July 2, 1863 dawned sunny and humid. While the Union troops who missed the first day’s fight had arrived by early morning, men from Longstreet’s corps battled the heat and long roads to arrive at Gettysburg by late afternoon. One particularly “ square and solid

” looking commander in gray looked over the fields to his direct front and noticed Union troops and artillery across the Emmitsburg Road in a peach orchard. The big guns, in fact, opened on them at their arrival. One of his brigade commanders, William Barksdale, begged, “General, let me charge!” The commander calmly told him to wait – their fight would come soon enough.1

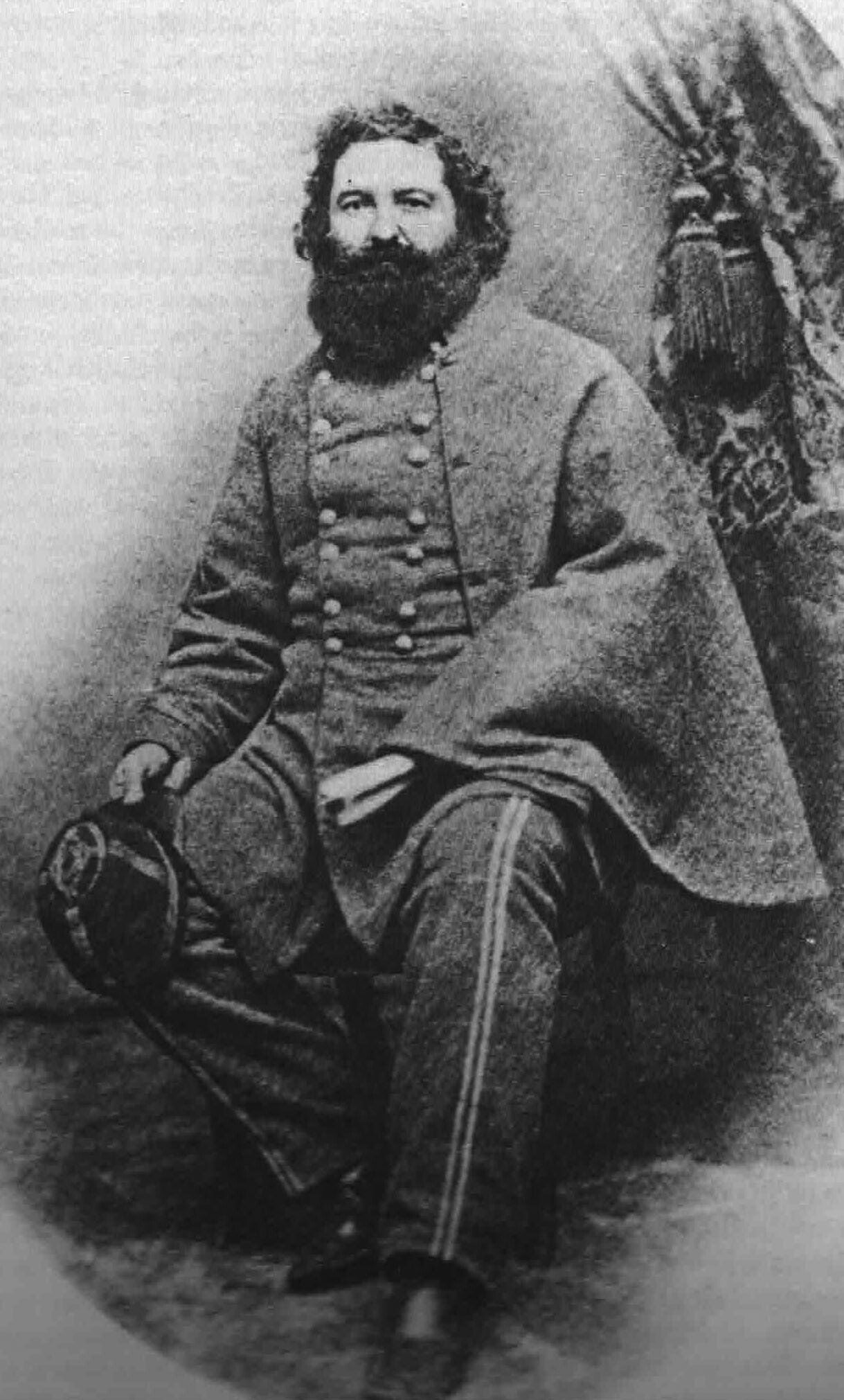

He was 42-year-old Lafayette McLaws.

Named for the famous Marquis de Lafayette – a popular appellation in the early 19th century, Lafayette Huguenin McLaws was the middle child of five children born to James and Elizabeth Huguenin McLaws, born on January 15, 1821 near Augusta, Georgia. His family and friends, understandably, simply called him “Mac”. His family was not wealthy, and Lafayette attended the local public schools. Upon graduation, he attended the University of Virginia until he was appointed to West Point at the age of 17. The class of 1842, which included McLaws, was also comprised of many of the yet future Civil War’s shining stars, including participants of the Battle of Gettysburg: James Longstreet, John Reynolds, Seth Williams, Abner Doubleday, Richard Anderson, John Newton, and George Sykes. McLaws cultivated a particularly close friendship with an underclassman named Ulysses S. Grant. The friendship lasted, in spite of the war, throughout their lives.2

McLaws served in the War with Mexico, where he became acquainted with General Zachary Taylor. McLaws participated in the Battles of Monterrey and Vera Cruz, but a serious stomach illness forced him to leave the front and serve as a recruiter. He was then sent to serve as the assistant adjutant general at the Department of New Mexico for two years. During this time, he married Zachary Taylor’s niece, Emily Taylor, in Jefferson County, Kentucky. The union was a happy one; seven children were born to the couple.3

Lafayette continued to serve as a Federal officer until his home state seceded in early 1861. He resigned his commission on March 23 of that year and promptly offered his services to the Confederacy. He began the war as a lieutenant colonel, commanding the 10th Georgia Infantry. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in September of that year. Noticed for his bravery at the Battle of Williamsburg, he rose to the rank of major general on May 23, 1862.4

McLaws served as a division commander under his fellow West Point cadet, James Longstreet. During the Peninsular Campaign, the wounding of army commander Joe Johnston necessitated that General Robert E. Lee assume command of the Army of Northern Virginia.

For the remainder of 1862, McLaws commanded his division of Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi troops. He participated in the Battles of Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. With the death of Lee’s top lieutenant commander, General Thomas J. Jackson, after his mortal wounding at Chancellorsville, some thought that General McLaws would rise to corps command. This, however, was not the case. Lee instead selected the crippled Richard Ewell to take Jackson’s corps, and, after dividing his two immense Confederate corps into three, Lee gave the new Third Corps to A.P. Hill.

His newly organized army then wended its way through the mountains toward Pennsylvania.

One would think that, since Longstreet and McLaws had known each other from their West Point days, and since both retained their separate friendships with the Union’s star commander, Ulysses S. Grant, that the pair were also friendly with each other. That was not the case, and their rancor toward each other became evident at Gettysburg.

Longstreet’s corps reached Gettysburg late in the afternoon of July 2, 1863 – after a full day of fighting had already taken place the previous day. The Union army, under the direction of new commander George Meade, was already present and, for the most part, deployed. After a grueling march in intense heat, with lack of sleep and nourishment, McLaws’s Division were weary upon their arrival on Seminary Ridge. They were, nevertheless, eager to get into the fight.

When McLaws’s men reached their line of deployment, McLaws noticed that the Peach Orchard, on the Emmitsburg Road, was already full of men in blue, complete with artillery – which began firing upon them as soon as the men in gray and butternut arrived. Longstreet ordered McLaws to attack “up the Emmitsburg Road” to flank the Federal line. McLaws protested that the road was filled with enemy soldiers – more than he had in his division. Longstreet didn’t believe him and told him to go. As McLaws prepared his men to advance, Longstreet changed the order, and told McLaws to wait for Hood’s Division.5

McLaws’s four brigades were led by Generals William Barksdale, Joseph Kershaw, Paul Semmes and William Wofford. In all, his division numbered seventeen regiments and two legions, Cobb’s and Phillips’s. The latter two were units that consisted of infantry, artillery, and cavalry.

Barksdale’s troops attacked Union forces in the Peach Orchard, and while they eventually succeeded in capturing the field, they paid a costly price for their victory, including the death of their commander. Kershaw, Semmes, and Wofford attacked Union troops in the Wheatfield with high casualties. Semmes was mortally wounded in the fight. Additionally, General Hood had been severely wounded early in the fight en route to Devil’s Den. It was a high price to pay for land that no one had actually wanted. McLaws was upset with the outcome, and told his wife that the “battle of the Peach Orchard was unnecessary and the whole plan of battle is a very bad one.”6

McLaws was also irked at General Longsteet. He wrote to Mrs. McLaws that “during the engagement he was very excited, giving contrary orders to everyone and was exceedingly overbearing. I consider him a humbug, a man of small capacity, very obstinate, not at all chivalrous, exceedingly conceited and totally selfish. If I can it is my intention to get away from his command.”7

Mac would soon have his chance.

After Gettysburg, Longstreet’s Corps traveled to Tennessee to help General Braxton Bragg, who was having issues with the tenacious Union army there. At the Battle of Knoxville, on November 29, 1863, Longstreet saw that the city was well fortified against his men. He noticed that a garrison at the northwestern corner of the city might be taken, and give them the impetus they needed to gain an advantage. He ordered McLaws to take the fort.

“The reasons for McLaws’s officers to not attack Fort Sanders,” explained one post-war journalist, “was that the ground was not reconnoitered and the depth of the ditch around the fort was not known.” The deep ditch was passable but without a thorough understanding of his task, McLaws was reluctant to waste the lives of his men. He had remembered Gettysburg.8

Longstreet blamed McLaws for the Union victory at Knoxville and had him arrested. A court-martial hearing, however, exonerated him. The rancor between the two generals by this time was impossible to mend, and McLaws was sent back to Georgia to fight Sherman and his March to the Sea.9

McLaws spent the remainder of the war in and near Savannah, Georgia, in an attempt to protect it from Sherman’s troops. He was on his way from the battlefield to Savannah on April 9, 1865, when he heard of Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant. His command was part of Joe Johnston’s army, which surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina a few weeks later on April 26, 1865.10

After the war, McLaws returned to his family, and they settled in Savannah, a town with which he became enamored during the conflict. Three of his seven children were born after the war: Anna Lee, Virginia, and Elizabeth Violet. Never good with money management, McLaws attempted several different businesses, including selling insurance. When Ulysses S. Grant was elected to the Presidency, the new Commander-in-Chief remembered his friends from the South. Longstreet was named Minister to Turkey, and Lafayette McLaws was given the title of Postmaster for the State of Georgia. Grateful for the position, McLaws visited Grant and asked him, “Can you tell me, General, how to make and save money?” Grant replied with a smile, “My dear Mac, I have not the slightest idea in the world.”11

Back in his native Georgia, McLaws was named the first president of the Sons of the Confederacy in that state, and held an honorary position in that association for the rest of his life. His chapter often presided at Memorial Day ceremonies in Atlanta, Savannah, and other cities.12

McLaws did not like to talk about Gettysburg, but preferred to discuss and write about the Maryland Campaign, which he often did at reunions and historical events. When Longstreet was blamed for the loss at Gettysburg by Jubal Early, William Pendleton and others after General Lee’s death, McLaws defended his old commander, in spite of their previous enmity. When Pendleton published that Lee had ordered Longstreet to attack the Union flank at first light in the morning of July 2, 1863, McLaws knew that Longstreet’s Corps had not yet arrived. He cannily explained, “I do not think General Lee would have ordered a main assault to be made…from information gained by a hasty reconnaissance…before the enemy had concentrated its forces….It cannot be doubted but that the enemy expected us to attack...they were prepared for us…I do not suppose General Lee would have ordered his army to attempt to do that which the enemy expected and wished us to do, especially when there were other and better ways to attack him.” He ended with, “ I think it is a grave assumption…to assert that because Longstreet’s Corps did not assault at daylight, the Battle of Gettysburg was lost.”13

McLaws was indeed one who did not dwell on past recriminations. He believed in looking to the future, not wallowing in sorrow over the past.

Emily McLaws died in 1890 at age 65. Lafayette followed her seven years later, on July 24, 1897, as the result of many years of dyspepsia and “acute indigestion”. He was 76. He was buried in Savannah with full military honors.14

“He was this city’s defender,” wrote an Atlanta journalist. “McLaws will always represent to our countrymen the thoroughbred, well-trained, steady, reliable military leader.”15

While he could be profane and cantankerous, McLaws was also intelligent, capable, and honorable. War often brings out the worst in people, but Lafayette McLaws, it seems, lived up to the memory of the nobleman for whom he was named, as “that gallant soldier of the Confederacy.”16

Sources: A.P. Hill Family Tree, Ancestry.com. A.P. Hill Participant Accounts File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography

. Vol. 3, New York, 1889. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee

. Vol. 4, New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1935 (reprint, 1963). Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day

. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. The Richmond Whig, 7 April, 1865. The Richmond Whig, 10 April, 1865. The Richmond Whig, 11 Apr. 1865. Robertson, James I. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior

. New York: Random House, 1987. Rollins, Richard, ed. Pickett’s Charge! Eyewitness Accounts

. Redondo Beach, CA: Rank and File Publications, 1994. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders

. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

End Notes:

1. A.P. Hill Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Robertson, p. 5.

2. Pfanz, p. 115. Warner, p. 135.

3. Pfanz, p. 115.

4. Robertson, pp. 31-33.

5. Drake, p. 226. Warner, p. 135.

6. Robertson, p. 98. Pfanz, p. 116. Hill’s war record lists him as 5’10” tall – not little by any means. The diminutive sobriquet might stem from childhood since he was the youngest of his family, or his thin frame, or possibly, at least in the army, in part due to his inability to get along with his commanders.

7. Ibid.

8. Robertson, pp. 187-188.

9. Pfanz, p. 28.

10. Ibid.

11. A.P. Hill Participant Accounts, GNMP.

12. Rollins, p. 36.

13. Drake, p. 226. Richmond Whig, 10 Apr., 1865. A.P. Hill Family File, Ancestry.com.

14. Richmond Whig, 7 Apr., 1865. Richmond Whig, 11 Apr., 1865. Robertson, p. 321.

15. Richmond Whig, 11 Apr., 1865.

16. Freeman, p. 492.