Lincoln Day by Day

by Diana Loski

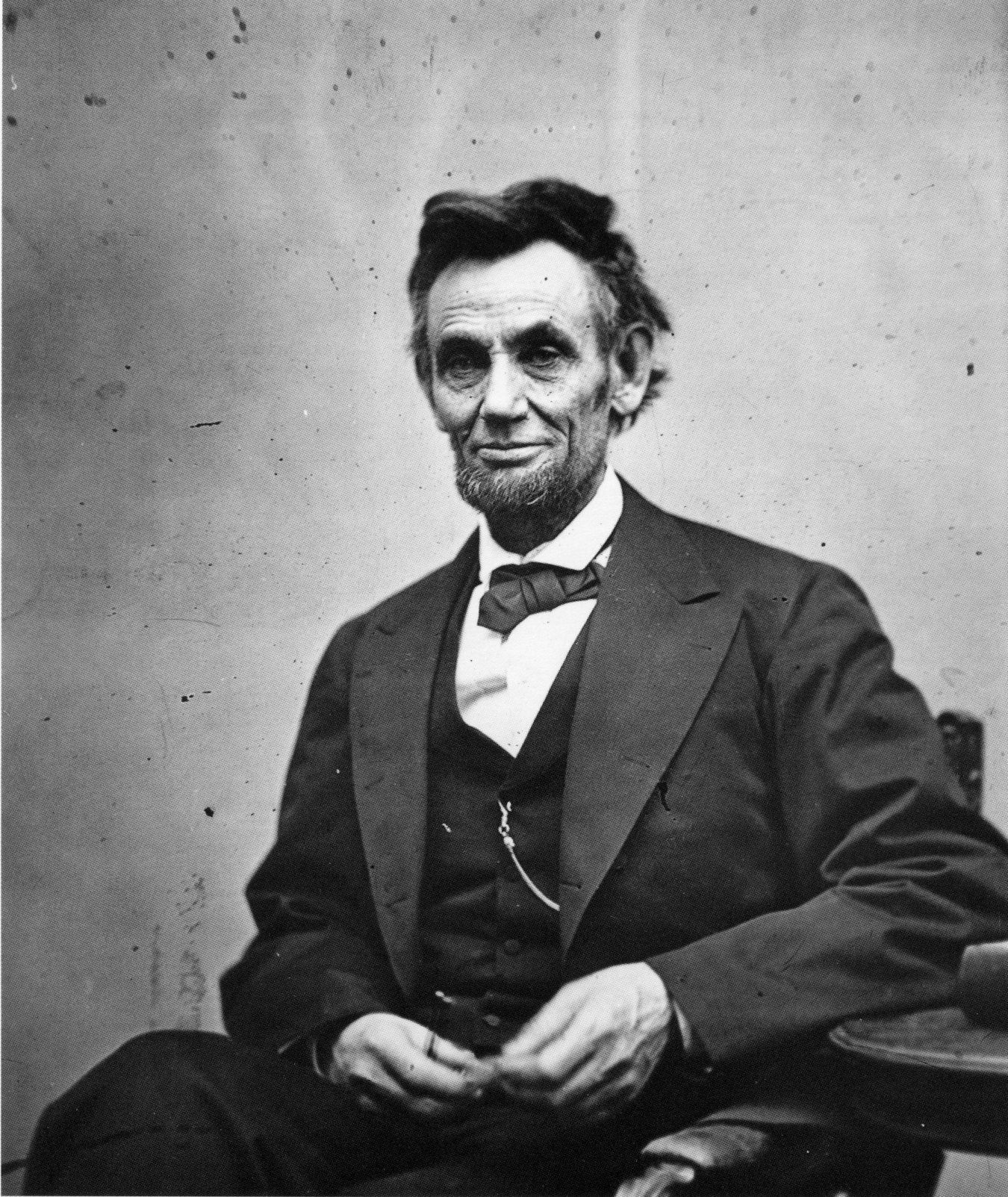

Abe Lincoln (Library of Congress)

Robert Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s eldest son, always regretted that he and his father were not as close as he had wished. Not only was his father away much of the time during Robert’s childhood, riding the circuit as a country lawyer, but once elected to the Presidency, Lincoln’s time was rarely his own. “Thence,” Robert remembered, “any great intimacy between us became impossible. I scarcely had ten minutes to talk with him during his Presidency, on account of his constant devotion to business.”1

A day in the Lincoln White House comprised an overflowing schedule. In fact, Lincoln had to stick to the schedule in order to complete the necessities of his service of Commander-in-Chief during the difficult Civil War years.

Lincoln rarely slept, especially after losing his son, Willie, in February 1862 of typhoid fever. Every Thursday for months, when the President had a minute or two to spare, he went into the room where Willie had died, locked himself in alone, and spent part of the afternoon remembering his eleven-year-old son. Always rising early, Lincoln spent an hour before breakfast going through correspondence and answering letters. For the first year of the war, Lincoln read the newspapers, but by 1862, he left that job to his secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. They also sorted his mail, discarding the threats, forwarding what could be taken care of in another department, and giving only the most essential items for the President to see.2

Lincoln was not a person who relished meals, especially when he was preoccupied. Breakfast was usually one egg, bacon and coffee. Lunch, if he had time for it, was often an apple and a glass of milk. Sometimes, he would enjoy a biscuit too. He rarely ate dessert, but enjoyed apple pie. Mary Lincoln once commented to a friend about dinnertime with the Lincolns, “We dine in the plainest manner.” 3

Between meals, Lincoln spent mornings with his Cabinet or receiving visits from dignitaries or other government officials. His afternoons were taken up with office seekers who thronged the Executive Mansion, sometimes standing in a line on the stairs waiting to be admitted into the President’s office. Sometimes the relentless office seekers – especially during the first year of Lincoln’s Presidency – remained so late that Lincoln had another exit created in his office so that he could slip away.4

On the occasional afternoon, if he found time, he took a carriage ride with his wife or walked up to the Capitol building.

Many evenings found the President working in his office until late at night, writing letters, reading news of the war, or accepting a late visitor. Tad, the Lincolns’ youngest son, often fell asleep in the President’s office on the floor, or, if the President wrote letters in his room, Tad would fall asleep in his father’s bed. (Mrs. Lincoln had a separate, but adjoining, chamber.) Lincoln would then pick up his slumbering child and carry him to his own bed. If Tad had a nightmare – a frequent occurrence since Willie’s death – Lincoln would leave Tad in his bed and work throughout the night. While Lincoln had regretted the lack of days and years with Robert, after Willie’s death he spent as much time with possible with his youngest son. Tad often burst in on his father’s meetings, and even managed to get those who could not secure a meeting with the President to find a way into Lincoln’s office.5

Lincoln also spent many evenings at the Telegraph Office near the White House, especially if a battle was imminent.

During the summer months from 1862 through 1864, Washington was excessively hot. The crowds, the nearby marshes with their miasmic atmosphere, the humidity, and the stench from the soiled streets had not only bred disease that led to the death of Willie Lincoln, it exacerbated Mary Lincoln’s frequent migraines. To bring relief to the family, the Lincolns spent summer nights at the Soldiers Home, located a few miles north of the city. One of the Presidential assassination attempts took place as Lincoln rode to the summer home one August evening. As he neared the home, a shot rang out and a bullet pierced his top hat. Apparently, many knew his schedule. “It was impossible…to induce him to forego these lonely and dangerous journeys between the Executive Mansion and the Soldiers Home,” remembered his friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon. “A stranger to fear, he often eluded our vigilance; and before his absence could be noted he would be well on his way to his summer residence, alone, and many times at night.”6

Lincoln often eluded others when he decided to go to the theater, sometimes accompanied by a friend such as Lamon or Noah Brooks, but otherwise by himself. He had reached an agreement with two theater owners, one of them Ford’s, and silently slid through the stage entrance and seated himself in a balcony after the curtain had risen. “President Lincoln’s theater-going was usually confined to occasions when Shakespeare’s plays were enacted

,” remembered journalist Noah Brooks, “for, although he enjoyed a hearty laugh, he was better pleased with the stately dignity, deep philosophy, and exalted poetry of Shakespeare.” A day did not elapse, either, without Lincoln engrossed in a little reading, either poetry ( The Last Leaf

by Oliver Wendell Holmes and The Dream

by Lord Byron were favorites that he had committed to memory), Shakespeare (Macbeth

was his favorite play), or the Bible. He found solace, and escape, in reading.7

During the late summers of the Lincoln Presidency, from 1862 through 1864, even the Soldiers Home was too oppressive for Mary Lincoln. She took Tad and Robert to New England, New York, or the mountains of Pennsylvania for weeks. This was the reason that Lincoln was alone at times heading toward the Soldiers Home or with his excursions to the theater.8

Life in the White House was lonely for Mary Lincoln, due to her husband’s long and tedious schedule. “I consider myself fortunate,” she wrote to a friend, “if at eleven o’clock, I once more find myself, in my pleasant room and very especially, if my tired and weary husband is

there, waiting in the lounge to receive me.”9

During the winters and springs of Lincoln’s tenure, he opened the White House twice a week for what he called “levees

” or meetings with the public. “Nothing could be more democratic than these gatherings of the people at the White House

,” remembered Noah Brooks. These gatherings took place, when the crowds were particularly large, in the East Room; otherwise, with a smaller populace, the meetings occurred in Blue Room or the Red Room – both used as state rooms. Lincoln and his Cabinet called them “the handshake days”, and some of Lincoln’s Cabinet escaped them if they could. As many as four thousand people came to the White House during one of these days, and the Lincolns greeted each one with a handshake. One European dignitary, who witnessed one of these levees, remarked, “One goes right in as if entering a café.”10

As the war progressed, and as the wounded poured into hospitals in and around Washington, both Abraham and Mary Lincoln spent afternoons and evenings visiting the sufferers. Mary brought small cakes from a basket; Lincoln shook their hands and spoke encouragingly to them.11

When he could get time away from his duties in the Executive Mansion, Lincoln traveled to review the troops, to confer with his generals and to visit the enlisted men. “Mr. Lincoln’s manner toward enlisted men, with whom he occasionally met and talked

,” wrote Noah Brooks, “was always delightful in its bonhomie and its absolute freedom from condescension.” After reviewing one military parade, Lincoln remarked, “It is a great relief to get away from Washington and the politicians. But nothing touches the tired spot.”12

The four years of war definitely, and adversely, affected the 16th President. Day by day and year by year, he held the broken nation, and with a strength of will managed to hold it together, with little respite, for the nation he hoped to save, and the people he willingly served.

Sources: Baker, Jean H. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography . New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008 (originally published in 1987). Brooks, Noah. Washington D.C. in Lincoln’s Time . Edited by Herbert Mitgang. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1989 (originally published in 1958). Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln at Home: Two Glimpses of Abraham Lincoln’s Family Life . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. Ford’s Theater Museum, Washington, D.C. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Lamon, Ward Hill. Recollections of Abraham Lincoln . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994 (originally published in 1911). Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years . New York: Galahad Books, 1993 (originally published as two volumes in 1926 and 1939).

End Notes:

1. Goodwin, p. 541.

2. Donald, p. 29. Baker, p. 213. Brooks, p. 245. Sandburg, p. 402.

3. Ford’s Theater Museum, Washington, D.C. Baker, p. 200.

4. Sandburg, p. 406.

5. Goodwin, pp. 505, 664-665.

6. Lamon, p. 270.

7. Lamon, p. 122. Brooks, pp. 71-72.

8. Donald, pp. 85, 87, 104.

9. Baker, p. 226.

10. Brooks, p. 69. Baker, pp. 197, 199.

11. Brooks, p. 77. Sandburg, p. 403.

12. Brooks, pp. 77, 55.

Editor's Note:

The excessive heat and humidity in Washington during the summer of 1863 also extended into Pennsylvania. There are myriad accounts of soldiers who described in detail the high temperatures in their march toward Gettysburg through the third day of fighting, especially during Pickett's Charge.