A Sad Day for Us": Remembering Pickett's Charge

by Diana Loski

Pickett's Charge: The Gettysburg Cyclorama

(Author Photo)

It was a splendid exhibition…Men were falling right and left.1

Arguably, the most famous portion of the Battle of Gettysburg was the epic finale when thousands of Confederates bravely and grimly marched at the double quick across nearly a mile of open field toward the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. It was the fight that not only decided the battle, it was a moment that began the demise of the Confederacy, although no one realized it at the time. The attack is officially known as Longstreet’s Assault, but it is more commonly known as Pickett’s Charge. It is named for Major General George E. Pickett, who led one of three divisions on that July 3rd afternoon in 1863.

Much has been written about the charge, but there remains so much that is unknown about it. The question of how many men made the charge is still a subject of debate. Because it is not known how many participated in the charge, it is impossible to know the extent of the casualties, especially for the men in gray and butternut.

The National Park Service conservatively estimates that 12,000 Confederates made the charge, although it was likely more. The reason for that number is that, of the three divisions who participated, two of them had already lost a significant number due to their participation in the fight on July 1. From Longstreet’s memoirs, the general recounted his argument with General Lee over the charge that he believed would fail: “I have been a soldier all my life,” he said, “and I should know as well as anyone, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.”2

Although the two divisions who were involved in both July 1 and Pickett’s Charge were not in Longstreet’s Division, he nevertheless would have taken the losses into account. Some of the divisions numbered more than five thousand men. General Hood’s Division, for example, numbered nearly 8,000. General Stuart’s cavalry division numbered at least that many as well.

It is important to note that many Confederates who were wounded July 1 still participated in the charge. One member of the 26th North Carolina remembered: “All the men that were not too severely wounded to bear arms were sent from the Hospital to their companies” He continued: “The cooks were given muskets…in fact, everything was done to get as many fighting men in the ranks as possible.”3

In addition to the three divisions who were definitely part of the charge, it appears that at least some members of a fourth division, commanded by General Richard H. Anderson, part of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps, also participated in the charge. General Cadmus Wilcox, who led a brigade from that division, was definitely part of Pickett’s Charge. He said: “General Lee, I came to Pennsylvania with one of the finest brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia and now my people are all gone. They have all been killed.”4

Another facet to consider in estimating the number of participants in Pickett’s Charge is to remember that General Lee was not a foolish commander. He knew the risks of a frontal assault, and had to assume that the entire Union army was entrenched and ready for his men. He would not have thrown an insufficient force across such a massive field, especially with so much at stake. He would have sent as many as he possibly could, which explains why cooks and walking wounded joined the attack.

George Pickett is another subject for debate for the famous charge that bears his name. At age 38 in 1863, Pickett had already been widowed twice and was engaged to be married for a third time. He admired President Lincoln, because as a Congressman in 1846, Lincoln had helped Pickett secure a position after Pickett had graduated last in his class at West Point. Pickett did not admire General Lee, and Lee reciprocated the less-than-cordial feelings. It appears that Lee, who was on intimate terms with most of the ancestral families of Virginia, and was at one time the commandant of West Point, did not believe Pickett was up to par for one with such a high command. The loss of so many Confederate general officers in prior battles necessitated the rise in rank of those who otherwise would never have been in such a lofty position.

While enroute to Pennsylvania, a gushing civilian in Maryland asked General Lee for a lock of his hair. Lee replied that he had none to spare, but “he was confident…that General Pickett would be pleased to give them one of his curls.” Lee often chided Pickett about his hair being too long for a soldier on duty. Pickett heard Lee’s latest remark and was offended. He knew he had not measured up in Lee’s eyes. He was eager to prove himself at Gettysburg.5

While the divisions of General Isaac Trimble and General James Pettigrew had already been in battle on July 1, Pickett’s men were yet untested in battle and had only arrived in Gettysburg the evening before the charge. Numbers for the men in Pickett’s Division range from 4800 to 5400. Since Pickett’s Official Battle Report for Gettysburg is missing, and it is suspected that it had been missing from July 1863, there is no way to substantiate how many men were available in Pickett’s Division.

On the Union side, General George Meade strongly suspected that General Lee would attack him frontally on July 3. At his council of war on the night of July 2, Meade said to General John Gibbon, who was part of General Hancock’s Second Corps defending Cemetery Ridge, “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front. He has made attacks on both our flanks and failed, and if he concludes to try again it will be on our center.”6

It was a classic Napoleonic maneuver to hit the enemy’s center after trying their flanks. It often worked for Napoleon, which was why he wrote a book on the art of warfare. Lee was a by-the-book general, and had studied extensively that particular book. In earlier battles, against army commanders who were much younger and inexperienced with the outmoded Napoleonic tactics, Lee usually prevailed. Meade, however, was old enough to have studied Napoleonic warfare, and recognized it. When the Confederates attacked the Union center line, Meade was prepared.

Not only were the Federals expecting the frontal charge, they outnumbered the Confederates and were well hidden on elevated ground behind a stone wall.

Friday, July 3, was a hot day. It dawned “clear and bright”, with early fighting on Culp’s Hill – as Lee tried one last time to turn the Union flank. That conflict ended about 11 a.m. with heavy casualties on the Confederate side. As the Southerners gathered on Seminary Ridge, the Union men stayed on their line of defense, eating hardtack and waiting for Lee’s next move. It came at about 1 p.m. One of Pickett’s survivors remembered: A single gun from our side broke the stillness.” The Federal guns replied, and a two-hour artillery barrage ensued. “The very ground shook,” one Virginian recalled. “It was simply awful, the bursting of shells, the smoke and the hot sun combined to make things almost unbearable for our men.”7

The Union side was equally uncomfortable. In addition to lying prone to avoid the screaming shells, the heat of the day made one soldier notice “the sweat was running off my face until it formed a muddy spot beneath.”8

For a few minutes, the Confederate gunners found their marks. The Union did as well. The recent rains, however, had resulted in muddy ground, and the cannon wheels soon became embedded, changing the trajectory. Smoke from the fields obscured the targets, causing the shells to overshoot the Union line. Shells strayed to Culp’s Hill and to field hospitals far behind the lines. One wounded soldier at the George Spangler Farm remembered watching the distant barrage from a barn window. “There I had a fine view of the bursting of shells coming in one direction…there were at one time six explosions of shells in one moment…the danger was becoming so great that every man was removed…the surgeon who had been in shortly before looking at my wound ran for his life.” Most who had later written about the terrible barrage agreed it lasted about two hours. Then it grew quiet. 9

A light breeze blew across the field between Cemetery and Seminary Ridges, revealing a gray line – Pickett’s troops – and a mixture of gray and butternut uniforms – revealing Trimble’s and Pettigrew’s Divisions. The two latter generals were new to their commands. Pettigrew had taken over for Harry Heth, who had been severely wounded on the first day’s battle. Trimble received William Dorsey Pender’s troops, as Pender had been mortally wounded by a shell on the second day.

As soon as the Confederates stepped out from the woods on Seminary Ridge, the Union artillery fired upon them, from the guns on Little Round Top and on down the line. “We had a splendid chance at them,” recalled artillery battalion commander Freeman McGilvery, “and we made the most of it…We could not help hitting them at every shot.”10

Arguably, the most famous portion of the Battle of Gettysburg was the epic finale when thousands of Confederates bravely and grimly marched at the double quick across nearly a mile of open field toward the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. It was the fight that not only decided the battle, it was a moment that began the demise of the Confederacy, although no one realized it at the time. The attack is officially known as Longstreet’s Assault, but it is more commonly known as Pickett’s Charge. It is named for Major General George E. Pickett, who led one of three divisions on that July 3rd afternoon in 1863.

Much has been written about the charge, but there remains so much that is unknown about it. The question of how many men made the charge is still a subject of debate. Because it is not known how many participated in the charge, it is impossible to know the extent of the casualties, especially for the men in gray and butternut.

The National Park Service conservatively estimates that 12,000 Confederates made the charge, although it was likely more. The reason for that number is that, of the three divisions who participated, two of them had already lost a significant number due to their participation in the fight on July 1. From Longstreet’s memoirs, the general recounted his argument with General Lee over the charge that he believed would fail: “I have been a soldier all my life,” he said, “and I should know as well as anyone, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.”2

Although the two divisions who were involved in both July 1 and Pickett’s Charge were not in Longstreet’s Division, he nevertheless would have taken the losses into account. Some of the divisions numbered more than five thousand men. General Hood’s Division, for example, numbered nearly 8,000. General Stuart’s cavalry division numbered at least that many as well.

It is important to note that many Confederates who were wounded July 1 still participated in the charge. One member of the 26th North Carolina remembered: “All the men that were not too severely wounded to bear arms were sent from the Hospital to their companies” He continued: “The cooks were given muskets…in fact, everything was done to get as many fighting men in the ranks as possible.”3

In addition to the three divisions who were definitely part of the charge, it appears that at least some members of a fourth division, commanded by General Richard H. Anderson, part of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps, also participated in the charge. General Cadmus Wilcox, who led a brigade from that division, was definitely part of Pickett’s Charge. He said: “General Lee, I came to Pennsylvania with one of the finest brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia and now my people are all gone. They have all been killed.”4

Another facet to consider in estimating the number of participants in Pickett’s Charge is to remember that General Lee was not a foolish commander. He knew the risks of a frontal assault, and had to assume that the entire Union army was entrenched and ready for his men. He would not have thrown an insufficient force across such a massive field, especially with so much at stake. He would have sent as many as he possibly could, which explains why cooks and walking wounded joined the attack.

George Pickett is another subject for debate for the famous charge that bears his name. At age 38 in 1863, Pickett had already been widowed twice and was engaged to be married for a third time. He admired President Lincoln, because as a Congressman in 1846, Lincoln had helped Pickett secure a position after Pickett had graduated last in his class at West Point. Pickett did not admire General Lee, and Lee reciprocated the less-than-cordial feelings. It appears that Lee, who was on intimate terms with most of the ancestral families of Virginia, and was at one time the commandant of West Point, did not believe Pickett was up to par for one with such a high command. The loss of so many Confederate general officers in prior battles necessitated the rise in rank of those who otherwise would never have been in such a lofty position.

While enroute to Pennsylvania, a gushing civilian in Maryland asked General Lee for a lock of his hair. Lee replied that he had none to spare, but “he was confident…that General Pickett would be pleased to give them one of his curls.” Lee often chided Pickett about his hair being too long for a soldier on duty. Pickett heard Lee’s latest remark and was offended. He knew he had not measured up in Lee’s eyes. He was eager to prove himself at Gettysburg.5

While the divisions of General Isaac Trimble and General James Pettigrew had already been in battle on July 1, Pickett’s men were yet untested in battle and had only arrived in Gettysburg the evening before the charge. Numbers for the men in Pickett’s Division range from 4800 to 5400. Since Pickett’s Official Battle Report for Gettysburg is missing, and it is suspected that it had been missing from July 1863, there is no way to substantiate how many men were available in Pickett’s Division.

On the Union side, General George Meade strongly suspected that General Lee would attack him frontally on July 3. At his council of war on the night of July 2, Meade said to General John Gibbon, who was part of General Hancock’s Second Corps defending Cemetery Ridge, “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front. He has made attacks on both our flanks and failed, and if he concludes to try again it will be on our center.”6

It was a classic Napoleonic maneuver to hit the enemy’s center after trying their flanks. It often worked for Napoleon, which was why he wrote a book on the art of warfare. Lee was a by-the-book general, and had studied extensively that particular book. In earlier battles, against army commanders who were much younger and inexperienced with the outmoded Napoleonic tactics, Lee usually prevailed. Meade, however, was old enough to have studied Napoleonic warfare, and recognized it. When the Confederates attacked the Union center line, Meade was prepared.

Not only were the Federals expecting the frontal charge, they outnumbered the Confederates and were well hidden on elevated ground behind a stone wall.

Friday, July 3, was a hot day. It dawned “clear and bright”, with early fighting on Culp’s Hill – as Lee tried one last time to turn the Union flank. That conflict ended about 11 a.m. with heavy casualties on the Confederate side. As the Southerners gathered on Seminary Ridge, the Union men stayed on their line of defense, eating hardtack and waiting for Lee’s next move. It came at about 1 p.m. One of Pickett’s survivors remembered: A single gun from our side broke the stillness.” The Federal guns replied, and a two-hour artillery barrage ensued. “The very ground shook,” one Virginian recalled. “It was simply awful, the bursting of shells, the smoke and the hot sun combined to make things almost unbearable for our men.”7

The Union side was equally uncomfortable. In addition to lying prone to avoid the screaming shells, the heat of the day made one soldier notice “the sweat was running off my face until it formed a muddy spot beneath.”8

For a few minutes, the Confederate gunners found their marks. The Union did as well. The recent rains, however, had resulted in muddy ground, and the cannon wheels soon became embedded, changing the trajectory. Smoke from the fields obscured the targets, causing the shells to overshoot the Union line. Shells strayed to Culp’s Hill and to field hospitals far behind the lines. One wounded soldier at the George Spangler Farm remembered watching the distant barrage from a barn window. “There I had a fine view of the bursting of shells coming in one direction…there were at one time six explosions of shells in one moment…the danger was becoming so great that every man was removed…the surgeon who had been in shortly before looking at my wound ran for his life.” Most who had later written about the terrible barrage agreed it lasted about two hours. Then it grew quiet. 9

A light breeze blew across the field between Cemetery and Seminary Ridges, revealing a gray line – Pickett’s troops – and a mixture of gray and butternut uniforms – revealing Trimble’s and Pettigrew’s Divisions. The two latter generals were new to their commands. Pettigrew had taken over for Harry Heth, who had been severely wounded on the first day’s battle. Trimble received William Dorsey Pender’s troops, as Pender had been mortally wounded by a shell on the second day.

As soon as the Confederates stepped out from the woods on Seminary Ridge, the Union artillery fired upon them, from the guns on Little Round Top and on down the line. “We had a splendid chance at them,” recalled artillery battalion commander Freeman McGilvery, “and we made the most of it…We could not help hitting them at every shot.”10

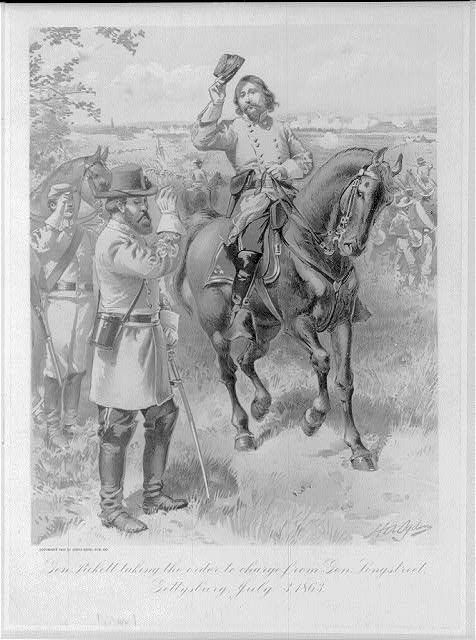

Pickett receiving orders from Gen. Longstreet

(Library of Congress)

“On they came, regardless of the carnage among them,” remembered one Union soldier. “Every moment was so appalling,” said another, “and the horrid scenes about us so dreadful we took no thought of the swift passing time.” A veteran from Pickett’s Division later wrote, “The enemy’s artillery opened on the columns and shells came screaming through the ranks.”11

The Confederates continued grimly on, at the double-quick in an attempt to get across the field. When they reached the Emmitsburg Road, a fence delayed them. At that point they were within range of Union muskets.

“When they reached the point about 300 yards distant, one of our boys fired at them,” remembered a man from the 1st Minnesota. “Lieutenant Ball spoke out, commanding us not to fire yet. ‘They are not close enough.’ I took a look at them and turned to the lieutenant and said, ‘We can [fire] our balls through their ranks [with] every shot from here.’” The lieutenant replied, “Fire away then.” The Minnesota soldier continued, “it seemed the whole corps had come to the same conclusion for the entire line fired at once.”12

All along their lines, the Confederates fell. “[Our] ranks were thinned at every step, and its officers rapidly cut down,” wrote one survivor from the 7th Virginia. Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s Divisions fared no better. “I had one in my company fall back,” remembered a North Carolina soldier. “As far as I could tell no one [else] fell back from our regiment that I saw. They were all cut down.”13

Only a small portion broke through at the Angle, led by Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead. He too was shot down, and died two days later in the summer kitchen at the George Spangler farm. Almost all who broke the Union line were either shot down or captured. The rest retreated back to Seminary Ridge. They were a mere fragment compared to those who had left the woods less than an hour earlier.

“In straggling groups, the survivors of that charge gathered in the rear of Seminary Ridge,” remembered one Confederate soldier, “ near the point from which they set out to do or die. It was a sad sight. Most of them were bleeding, numbers of them bathing their wounds in a little creek which ran along the valley, making its clear water run red, which others used to quench their burning thirst.”14

Another Virginian documented that “some of them were wounded and nearly all had marks of bullets about their clothes, and [were] the saddest set of men I ever saw, as we lamented the loss of our brave comrades we had left upon the field, many of them never to see again.”15

One soldier from Pettigrew’s Division plaintively remarked, “I could all but walk over the field on dead and wounded. I have never seen the like before.”16

Many of the survivors remembered seeing General Pickett, shaken and in tears, speaking to General Lee. Lee told Pickett to look after his division, thinking that there might be a Union counterattack. Pickett tersely replied, “ General Lee, I have no division now !” It appears that Pickett lost far more men than the 50 percent casualty number estimated by the National Park Service.17

Since Pickett’s Official Report is missing, it is impossible to know the exact number of casualties in his division. However, members of this unit have written their own memories of that day. Several mention that less than one thousand answered roll call the following day. If this is accurate, Pickett’s losses were indeed staggering, lending credence to his lament to General Lee. Of Pickett’s three brigade commanders, two were killed, one severely wounded. Of the thirteen colonels who led the regiments, all fell as casualties. Seven were killed, one died later of wounds, and the rest survived. In Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s divisions, the numbers were similar. Both division commanders were wounded. In fact, of the eight Confederate generals who participated in the charge, only three escaped harm: Pickett, Joe Davis, and John Lane. On the Union side, the Federals fared better, but still many were casualties. No Union generals were killed, but four were wounded: Hancock, Stannard, Gibbon, and Webb. There were many in the Union ranks killed and wounded as well.18

It was indeed a terrible fight, with significant repercussions. General Lee succinctly summed up the pivotal end to the battle by saying, “It was a sad day for us.”19

The same feeling of sadness pervades upon all who visit the field, one hundred and sixty years later.

The Confederates continued grimly on, at the double-quick in an attempt to get across the field. When they reached the Emmitsburg Road, a fence delayed them. At that point they were within range of Union muskets.

“When they reached the point about 300 yards distant, one of our boys fired at them,” remembered a man from the 1st Minnesota. “Lieutenant Ball spoke out, commanding us not to fire yet. ‘They are not close enough.’ I took a look at them and turned to the lieutenant and said, ‘We can [fire] our balls through their ranks [with] every shot from here.’” The lieutenant replied, “Fire away then.” The Minnesota soldier continued, “it seemed the whole corps had come to the same conclusion for the entire line fired at once.”12

All along their lines, the Confederates fell. “[Our] ranks were thinned at every step, and its officers rapidly cut down,” wrote one survivor from the 7th Virginia. Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s Divisions fared no better. “I had one in my company fall back,” remembered a North Carolina soldier. “As far as I could tell no one [else] fell back from our regiment that I saw. They were all cut down.”13

Only a small portion broke through at the Angle, led by Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead. He too was shot down, and died two days later in the summer kitchen at the George Spangler farm. Almost all who broke the Union line were either shot down or captured. The rest retreated back to Seminary Ridge. They were a mere fragment compared to those who had left the woods less than an hour earlier.

“In straggling groups, the survivors of that charge gathered in the rear of Seminary Ridge,” remembered one Confederate soldier, “ near the point from which they set out to do or die. It was a sad sight. Most of them were bleeding, numbers of them bathing their wounds in a little creek which ran along the valley, making its clear water run red, which others used to quench their burning thirst.”14

Another Virginian documented that “some of them were wounded and nearly all had marks of bullets about their clothes, and [were] the saddest set of men I ever saw, as we lamented the loss of our brave comrades we had left upon the field, many of them never to see again.”15

One soldier from Pettigrew’s Division plaintively remarked, “I could all but walk over the field on dead and wounded. I have never seen the like before.”16

Many of the survivors remembered seeing General Pickett, shaken and in tears, speaking to General Lee. Lee told Pickett to look after his division, thinking that there might be a Union counterattack. Pickett tersely replied, “ General Lee, I have no division now !” It appears that Pickett lost far more men than the 50 percent casualty number estimated by the National Park Service.17

Since Pickett’s Official Report is missing, it is impossible to know the exact number of casualties in his division. However, members of this unit have written their own memories of that day. Several mention that less than one thousand answered roll call the following day. If this is accurate, Pickett’s losses were indeed staggering, lending credence to his lament to General Lee. Of Pickett’s three brigade commanders, two were killed, one severely wounded. Of the thirteen colonels who led the regiments, all fell as casualties. Seven were killed, one died later of wounds, and the rest survived. In Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s divisions, the numbers were similar. Both division commanders were wounded. In fact, of the eight Confederate generals who participated in the charge, only three escaped harm: Pickett, Joe Davis, and John Lane. On the Union side, the Federals fared better, but still many were casualties. No Union generals were killed, but four were wounded: Hancock, Stannard, Gibbon, and Webb. There were many in the Union ranks killed and wounded as well.18

It was indeed a terrible fight, with significant repercussions. General Lee succinctly summed up the pivotal end to the battle by saying, “It was a sad day for us.”19

The same feeling of sadness pervades upon all who visit the field, one hundred and sixty years later.

The Pickett's Charge field today

(Author photo)

Sources: 153rd Pennsylvania File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Cleaves, Freeman. Meade of Gettysburg. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960. Compton, Edward Howard. “Reminiscences of Edward Howard Compton.” 7th Virginia File, U.S. Military History Institute, Carlisle, PA. Copy at GNMP. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee. Volume 3. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934. Gibbon, John. Personal Recollections. New York: 1928. Copy, GNMP. Gragg, Rod. Covered with Glory: The 26th North Carolina Infantry at the Battle of Gettysburg. New York: HarperCollins, 2000. Letter, Private Cureton to John R. Lane, June 22, 1890, 26th North Carolina File, GNMP. Loehr, Charles T. “The Old First Virginia at Gettysburg.” 1st Virginia File, GNMP. Rollins, Richard, ed. Pickett’s Charge! Eyewitness Accounts. Redondo Beach, CA: Rank and File Publications, 1994. Selcer, Richard E. Faithfully and Forever Your Soldier: George E. Pickett, CSA. Gettysburg: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. Stewart, George. Pickett’s Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1959.

End Notes:

1. Loehr, p. 28.

2. Stewart, p. 22.

3. Letter, Private Cureton to John R. Lane, GNMP.

4. Rollins, p. 178.

5. Freeman, vol. 3, p. 54. Selcer, p 30.

6. Gibbon, p. 145. Cleaves, p. 156.

7. Rollins, p. 61. Loehr p. 34. Temperature readings at Gettysburg College for the afternoon of July 3 registered in the shade at 88 degrees. It did not take the heat index or traversing a field in the blazing sun into account.

8. Stewart, p. 137.

9. The 153rd Pennsylvania File, GNMP. Stewart, p. 183.

10. Stewart, p. 187.

11. Rollins, pp. 245-246.

12. Ibid., p. 237.

13. Stewart, p. 179. Rollins, pp. 177, 267.

14. Loehr, pp. 36-37.

15. Compton, p. 25.

16. Gragg, p. 140.

17. Selcer, p. 35.

18. Stewart, p. 268. Selcer, p. 37.

19. Ibid., p. 272.