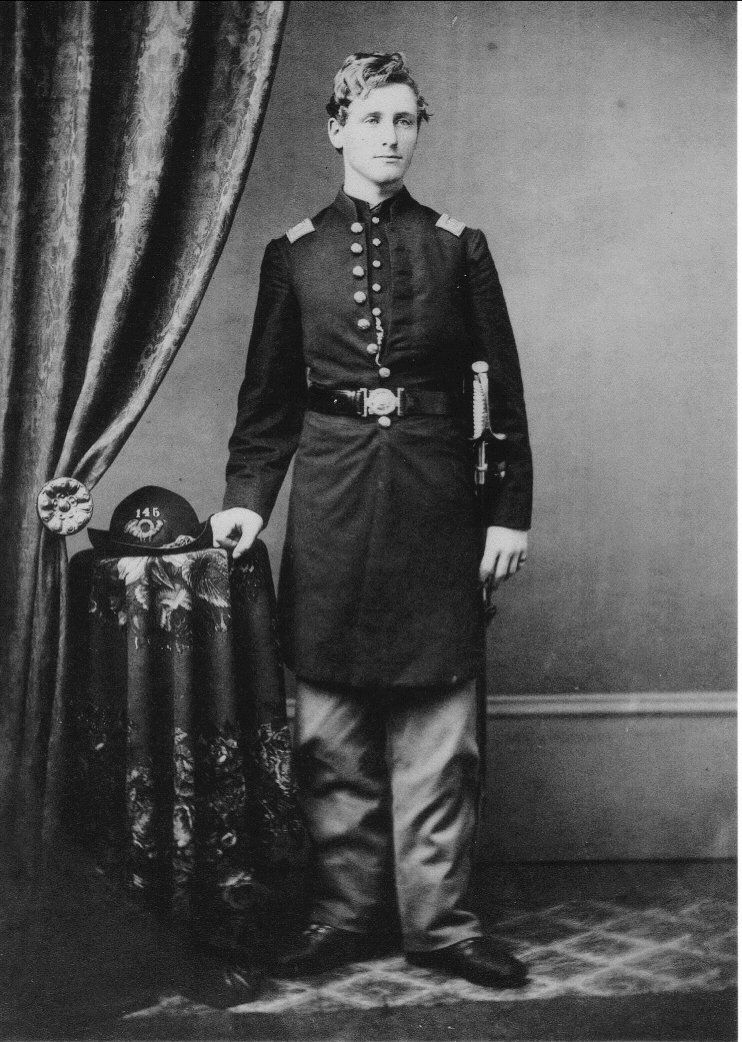

"I Had Great Hopes For Him"

Horatio Lewis & the 145th Pennsylvania at Gettysburg

by Gordon W. Gribble

As part of Colonel John Brooke’s brigade, the 145th and its members had outrun their comrades and were perilously close to capture. Among them was a young lieutenant, “brave, ambitious and hopeful” and greatly admired by the regiment. Only seventeen when he enlisted to fight for the Union, Horatio Lewis was meant to be a soldier.2

Horatio Farnham Lewis was the ninth of eleven children born to Marcus Lewis of Harbor Creek, Pennsylvania, near Erie. He had four brothers: Ammi Merchant, Harry, James, and Marcus, Jr., and four of the five served in the Civil War. They were descendants of William Lewis and his wife, Felicia, who came from Wales, arriving with their young son, William Jr., in 1632 – just twelve years after the Mayflower – and settled in Boston.3

Horatio had a strong interest in the military, and he mastered Hardee’s Tactics at a young age. By age 14 he had organized a military artillery unit, which became an attraction for parades in Erie, Buffalo, and Cleveland during the 1860 political campaign of Abraham Lincoln. Older brother Harry remembered, “When Abraham Lincoln was in Erie on his way to be inaugurated, Horatio and his artillery company fired a salute from the canal bridge at Swan Station. A premature discharge of the cannon sent the heavy hickory ramrod nearly against the train bearing Lincoln east to Erie.”4

When war came, Horatio enlisted with his cousin and best friend Franklin Gifford Lewis. They joined the newly organized 145th Pennsylvania Infantry on August 6, 1862. Horatio was only seventeen years of age when he was mustered into Company D of the regiment, but, in spite of his youth, he was soon promoted to Orderly Sergeant on September 5 and to Sergeant Major on September 25 of that same year.5

The 145th Pennsylvania Monument, Brooke Ave.

(Author Photo)

With very little training, the regiment left Erie on September 11, 1862 and reached Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in 36 hours. On September 17 the 145th joined the Union line at Antietam, being assigned to the 1st Brigade, 1st Division of the Second Corps.6

Following limited action at Antietam, the regiment was detailed to care for the wounded and to bury the dead. Some had lain on the battlefield for four days. The activity was so repugnant and shocking to the men that some 200 to 300 of them were “disqualified for duty.”7

The 145th saw action at Fredericksburg in December 1862. As they crossed the middle pontoon bridge over the Rappahannock and headed up Hanover Street, Horatio received his first wound. His brother Harry wrote, “My brother (a boy of 17), Horatio F. Lewis, was a sergeant major of the 145th. The next day (December 14) I found him in a home on Main Street. He had received a ball through the [right] foot, ripping the sole of a boot off, as they were scaling a fence on Sunken Road. His wound was as yet undressed, and he was covered in slime and mud.” Harry carried Horatio across the street, put him in a bed and quickly procured water at a nearby well. He then “tore up a pillow case, washed and did up the wounded foot, bathing it with water.” Horatio, wounded before the famous fight at Marye’s Heights, missed the infamous charge made by Union troops there. Unfortunately, his cousin Franklin participated, and was killed in the battle. His remains were grievously ruined. He was identified only by the documents on his body. His grave in Erie is empty.8

Horatio was transported to the St. Aloysius Civil War Hospital in Washington, D.C. to recuperate. While there he received a visit from President Lincoln, who was passing through to visit the wounded. Horatio was transferred to Crozier Hospital in West Chester, Pennsylvania, then returned home on furlough to recover. Horatio rejoined his unit, although he could barely walk, on January 7, 1863, where he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. He took command of Company D on March 6, 1863.9

On June 15, 1863, the Army of the Potomac was reorganized. Major General Winfield S. Hancock took over command of the Second Corps. Brigadier General John C. Caldwell took command of the 1st Division, and Colonel John R. Brooke commanded the 4th Brigade. His troops included the 145th Pennsylvania, the 27th Connecticut, the 2nd Delaware, the 64th New York, and the 53rd Pennsylvania regiments. Brooke’s brigade totaled 851 men, of which 202 were the men of the 145th Pennsylvania, as they marched toward Gettysburg and the fateful day that awaited them on July 2.

With his foot still injured, Horatio could not march. The regimental chaplain John H.W. Stuckenburg noted, “Soon after dark we came to Uniontown [Maryland]. Before entering the village, Lt. H. Lewis came weeping to the rear of the regiment, said he could go no further, but had never fallen out and didn’t want to do so now. I let Lt. Lewis ride my horse – which he did – thus keeping him up with the regiment. Next morning Gen. Hancock complimented us highly for our march the preceding day of 30 miles. Our men were completely worn out.”10

On July 1 the brigade left Uniontown, arriving in Taneytown near Gettysburg. The 145th bivouacked in the woods east of the Taneytown Road, awaiting further orders.

On July 2, the regiment broke camp and arrived with the rest of Caldwell’s Division at Gettysburg. They deployed on Cemetery Ridge, near the spot of the present-day Pennsylvania State Monument. They would not remain there. About 3 p.m. they watched in awe as General Dan Sickles moved his entire Third Corps, some 13,000 men, west of the main Union line, about ½ mile to the confluence of the Peach Orchard near the Emmitsburg Road, a position that Sickles perceived as more advantageous.11

The intrepid move by Sickles triggered Confederate General James Longstreet’s attack. The move by the Third Corps general has been debated and chastised ever since. Thomas Osborne of the 145th Pennsylvania recalled, “We do not know what it means, but soon learn that it is the Third Corps…..The formation is hardly made when Longstreet hurls his battalions against Sickles’ left with impetuosity and determination and then began one of the most remarkable encounters known in the annals of warfare.”12

It would also become one of the most deadly ones.

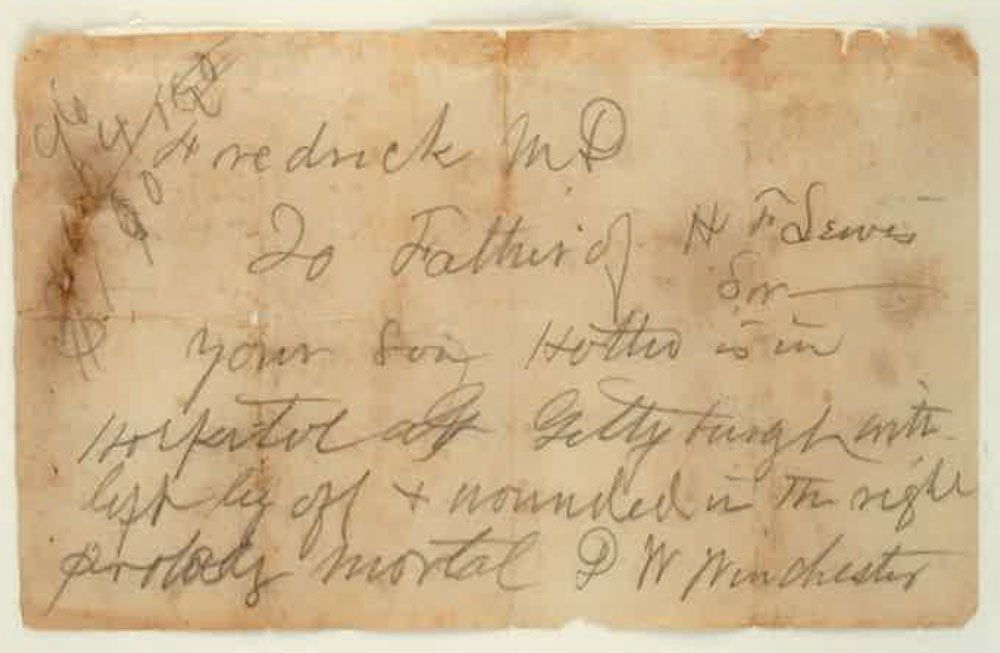

Telegram sent by Sgt. Winchester, July 1863

(Courtesy of Brent & Cathy Maher)

As Colonel Brooke’s brigade prepared to advance into the Wheatfield to help Sickles’ troops, their commander gave a patriotic speech: “Boys, remember the enemy has invaded our own soil!!! The eyes of the whole world [are] upon us! And we are expected to stand up bravely to our duty!”13

Like the rest of the brigade, the now 18-year-old Lieutenant Lewis was ready. He did not realize it was his last battle.

As the 145th Pennsylvania entered the Wheatfield, their exuberance, along with the rest of Brooke’s Brigade soon outpaced the rest of Caldwell’s Division. General Hancock wrote in his official report: “With his accustomed gallantry and energy, Brooke pushed his line further to the front than [any] other of our troops advanced during the battle, and gained a position impregnable from an attack in front, and of great tactical importance, but owing to the right flank being exposed, the brigade was compelled to fall back.”14

As the troops withdrew, many fell wounded. One of them was Lieutenant Horatio Lewis. In the vicinity of the Ledge of Rocks [present day Brooke Avenue], the young soldier was shot down in two places. His left thigh bone was shattered by a minie ball. He was also shot in the right leg, a less serious wound. During the obligatory retreat by Brooke’s Brigade, Horatio was left on the field for two or three days before he was discovered. Chaplain Stuckenburg visited the Second Corps Hospital on July 7 and saw the young lieutenant, who “had his leg amputated. He looked feeble and sallow, suffered a great deal (had been lying on the field till a rebel for 25 doll[ars] brought him into our lines to a house to their rear).” He added, “But they stole his water canteen, his money ab[out] 80 dollars, haversack et cet.” Horatio, in his condition on the field, had not been able to sleep. As was common for amputations, especially in for those in a weakened condition, the surgeons gave little hope for his recovery.15

Marcus Lewis received a telegram from Quartermaster Sergeant D.W. Winchester, with the terse message: “Your son Horatio is in hospital at Gettysburg with left leg off & wounded in the right probably mortal.” Marcus dispatched two of his sons, James and Ammi, along with the Reverend Doctor Edward Abiel Washburn of St. Mark’s Church in Philadelphia to be with Horatio.16

The two brothers and good reverend arrived in Gettysburg in time to be with their dying brother. Horatio passed away from his wounds on July 20, 1863. “He was a noble young man,” lamented Chaplain Stuckenburg. “There was an innocence and simplicity about him, which were well calculated to gain one’s affection. His loss is felt severely by us all. We loved him, we admired him. He is one of the many truly noble sacrifices given to our country.” The chaplain also remained near Horatio in his final hours. “He was calm and resigned when I saw him, and frequently, I was told, was found praying. The thought of his death greatly saddens me, for I loved him and had great hopes for him.”17

Like so many sad outcomes from Gettysburg, Horatio’s brothers returned to Erie with his remains. Lieutenant Lewis was buried in the Erie City Cemetery, after a funeral at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. His grave can be seen there today. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Post #359 in Fairview, Pennsylvania, is named for Horatio F. Lewis, notwithstanding the fact that several generals and colonels were proposed for this honor.

There is no one more deserving of it.

Sources: Dedication of keynote addresses of the 145 th Pennsylvania Monument, Sep. 11, 1889. Pennsylvania at Gettysburg . Vol. II, Harrisburg, PA: E.K. Meyers, State Printer, 1893. Hedrick, David T. and Gordon Barry Davis, Jr. I’m Surrounded by Methodists: Diary of John H.W. Stuckenburg, Chaplain of the 145 th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry . Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1998. History of Erie County, Pennsylvania . Chicago, IL: Warner, Beers & Co., 1884. Hutchinson, Matthew W. “Bringing Home a Fallen Son: The Story of Lt. Willis G. Babcock, 64 th New York Volunteer Infantry.” The Gettysburg Magazine, No. 30, 2004. Lewis, Harry W. The Erie Daily Times, Sep. 14, 1907. Lewis, Harry W. The Erie Daily Times, Feb. 12, 1909. Lewisiana: A paper published in 17 vols. January 1887-June 1907. Library of Congress Call No. GS69 (microfiche), compiled by Deborah Miller. Ofney, Sandra Sutphin. Passengers on the ‘Lion’ from England to Boston, 1632 and Five Generations of Their Descendants . Philadelphia, PA: Heritage Books, Inc. 1992. Osborn, Stephen Allen, 145 th Pennsylvania, Company G. “Reminiscence of the Civil War." Shenango Valley News, Greenville, PA, Apr. 2, 1915. Sauers, Richard A. “The 53 rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the Gettysburg Campaign.” The Gettysburg Magazine, No, 30, 1994. Telegram, Sgt. D.W. Winchester to Marcus Lewis, July 6, 1863. Original document owned by Brent & Cathy Maher.

End Notes:

1. Osborn, Shenango Valley News, Apr. 2, 1915.

2. Hedrick, p. 84.

3. Ofney, p. 355.

4. Lewis, Harry W. The Erie Daily Times, Feb. 12, 1909, p. 16.

5. Lewisiana, 12(9): 134, Mar. 1902.

6. History of Erie, PA, p. 485.

7. Ibid.

8. Lewis, Harry W. The Erie Daily Times, Sep. 14, 1907, p. 12.

9. Lewisiana, 12(9): 134, Mar. 1902.

10. Hedrick, p. 76.

11. Sauers, Gettysburg Magazine no. 11, p. 80.

12. Hedrick, p. 76.

13. Hutchinson, The Gettysburg Magazine, no. 30, p. 65.

14. Pennsylvania at Gettysburg, vol II, 11 Sep. 1889, p. 714.

15. Hedrick, p. 84.

16. Telegram, D.W. Winchester to Marcus Lewis, Jul 6, 1863.

17. Hedrick, p. 84.

Gordon W. Gribble is a native of San Francisco, California. Following his education, he was appointed Professor of Chemistry at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, where he has taught since 1968. He is now Emeritus. He is the great-great grandson of the Rev. Ammi Merchant Lewis, one of Horatio’s brothers. Professor Gribble passed a sabbatical year (2006-2007) at Gettysburg, where he spent many hours on the battlefield. He currently lives in Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Gettysburg, PA