Rufus Dawes: A True Defender

Rufus Dawes: A True Defender

by Diana Loski

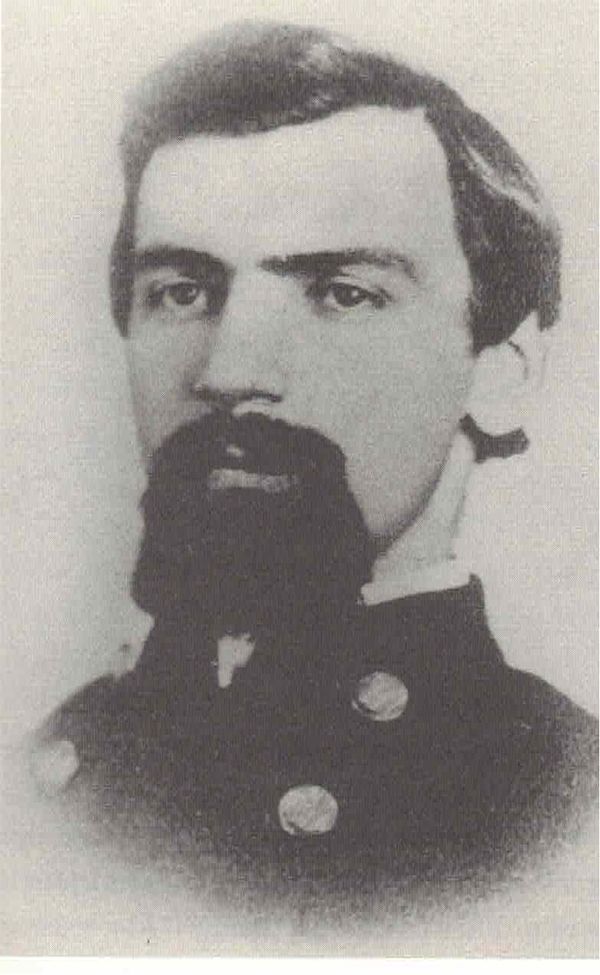

Colonel Rufus Dawes, USA

(U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA)

On Gettysburg’s first day, no one expected a fight, except General John Buford – who saw the men in gray coming toward town. Farther away than their Confederate counterparts, the Federal troops rushed toward the west of town in order to stop the advance of Lee’s army. One of many colonels who led volunteer regiments, and a volunteer military man himself, was Rufus Dawes – who had left the University of Wisconsin to fight for the Union. From childhood, he was always ready to fight for what was right – and for those who could not.

Rufus Dawes was born to settlers near Ohio’s first official town, Marietta. He was the second youngest son of Henry and Sarah Cutler Dawes. The day of his birth in 1838, July 4th, was a portent as to how this patriotic young man would serve his country.

Sarah Cutler Dawes, who was also born in Ohio, was the daughter of settlers, and the sister of the respected William Cutler, one of the famous members of the Marietta settlement. Situated on the banks of the Ohio river in eastern Ohio, Marietta was named for the ill-fated Marie Antoinette, wife of the French king Louis XVI. In spite of its namesake, Marietta thrived. The founders were made of stern genetics, and they had among their group the famed Revolutionary general Rufus Putnam, who was respected by both the immigrants and the native populace. Though General Putnam had died before 1838, Sarah Cutler Dawes remembered the old commander from her early years, and named her second son Rufus Dawes.1

Rufus and his siblings spent many days at their uncle’s farm, located six miles south of Marietta. “Here on the old Cutler place,” wrote one who remembered, “during the days of the Mexican War, frequently could be seen a group of four children, two boys and two girls, naming their pets after war heroes and playing bivouac and field.” The children were Rufus, his brother Ephraim, and his sisters Lucy and Sarah Jane.2

The Mexican War was anathema to the Dawes family, who were abolitionists. Since Marietta was just across the river from what was then western Virginia, many escaping that institution forded the river to Marietta, and received help from the citizens there. Rufus grew up understanding the evils of slavery, and from a young age was determined to defend the oppressed.3

Rufus Dawes attended Marietta College, graduating from there in 1860. He excelled in sports and scholarship. He also was recognized as a leader. During class one day, he learned that a bully had jumped on the back of another student and forced him to carry him up four flights of stairs to their dormitory. Dawes immediately sought the perpetrator, jumped on his back, and ordered him to do exactly what he had done to the oppressed student. “It was needless to say the punishment was effective,” recalled one of the students.4

In 1855, Henry and Sarah Dawes moved to Wisconsin, one of the newest states to emerge from the original Northwest Territory. Having achieved statehood just before Rufus turned ten years old in May 1848, Wisconsin offered inexpensive land and education. Rufus and his younger brother, Ephraim, traveled there with their parents. Alternating between Marietta College and his new home, Rufus was busy traveling between the two states. He also attended the newly established University of Wisconsin. He only completed a few classes when war exploded upon the nation in 1861.5

Upon hearing of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Rufus hurried to enlist. Living at that time in Juneau County, just northwest of Madison, Dawes signed up with the 6th Wisconsin – then only a three-month regiment. He enlisted as a private, but soon raised a company; he was elected captain of Company K. The regiment was officially mustered in August 1861.6

The 6th Wisconsin’s first battle occurred at the Rappahannock in August 1862. They continued to fight in all the major battles of the Civil War through 1864: Gainesville, Second Manassas, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Mine Run, The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Bethesda Church, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. During their three-year’s service in the war, the 6th lost 60% of their men to death and wounds. Dawes was “with them in every fight, yet never received the slightest wound, nor was in the hospital on account of sickness.”7

Dawes was soon promoted to major in 1862, to lieutenant-colonel in early 1863, full colonel in 1864, and retired as a brevet brigadier general in early 1865. He was a regimental commander at age 24 at Gettysburg – commemorating his 25th birthday as Lee’s army vacated the Pennsylvania town. He had “ a keen insight into whatever situation confronted him.” Another remembered that “he had a genius in handling men.”8

One instance that showed his talent for leadership was the famous “Whiskey & Quinine Order”. Quinine, which staved off malaria – an omnipresent threat when engaged in battles in the South, was available but bitter, and strongly disliked by the soldiers. In order to get them to ingest it, Dawes mixed it with the daily allowance of whiskey – which the soldiers often drank to excess. He decided that “every allowance of whiskey was mixed with one of quinine.” The effect was “a tonic” to the men, and kept them healthy while others suffered from, and sometimes succumbed to, the dreaded malaria.9

Dawes was never considered a martinet, and was beloved by his men. He possessed “the quiet word of encouragement, the helping hand, the arm raised to defend the weak”. He was also one who led from the front, never expecting his men to fight where he did not go first himself.10

He would prove that leadership skill with exactness at Gettysburg.

The 6th Wisconsin was part of the famed Iron Brigade. When they arrived at Gettysburg’s western fringe of town, Dawes and his men, the last of the brigade to arrive, were held in reserve on McPherson’s Ridge. Ordered to fight at any moment, Dawes had his regiment aligned and prepared. They saw a body wrapped in a blanket, carried from the field. It was their former commander and recent wing commander, General John Reynolds – but they did not realize it was him at the time. The new commander on the field, Abner Doubleday, rescinded the order to engage that Reynolds had given them. Stuck in the low ground between Seminary and McPherson’s Ridges, with Confederate bullets zipping around them, Dawes ordered his men at the double quick to the Chambersburg Pike.11

They would soon be hotly engaged in one of Gettysburg’s famous fights.

As the 6th Wisconsin advanced to the Chambersburg Pike, General Joe Davis’s Mississippi Brigade also advanced from the west to the same spot. The Mississippi men fired upon the Wisconsin men, which Dawes described as “terribly destructive”. The 6th pushed relentlessly on, charging into the men in butternut. Davis’s men retreated into the unfinished railroad cut.12

As the 6th Wisconsin pressed onward, there were three New York regiments in the vicinity, part of Lysander Cutler’s Brigade. Two of them, the 95th New York and the 14th Brooklyn, fell in line with the Wisconsin men, forming an extended line on their left flank. They fired on the Southern troops, who descended into the unfinished railroad cut. One of the New York men said that the arrival of the Wisconsin regiment “caused our hearts to beat fast with joy and thankfulness.” Dawes and his men had arrived at precisely the right time.13

Dawes had lost his horse in the charge, as the mare was shot in the chest. He continued, unflinching, on foot. As the blue line rushed to the cut, firing upon the beleaguered Confederates, the fight soon came to an end, with Dawes demanding the surrender of the Mississippi men. He asked one of the officers, “Where is the colonel of this regiment?” The officer, a major, ignorantly replied, “Who are you?” Dawes tersely answered that he was the commander of the regiment that had just bested them, and that they had better surrender or be shot. The major immediately gave Dawes his sword. In all, seven swords were handed to him that morning. They captured the 2nd Mississippi’s battle flag, and about 250 prisoners.14

Rufus Dawes was born to settlers near Ohio’s first official town, Marietta. He was the second youngest son of Henry and Sarah Cutler Dawes. The day of his birth in 1838, July 4th, was a portent as to how this patriotic young man would serve his country.

Sarah Cutler Dawes, who was also born in Ohio, was the daughter of settlers, and the sister of the respected William Cutler, one of the famous members of the Marietta settlement. Situated on the banks of the Ohio river in eastern Ohio, Marietta was named for the ill-fated Marie Antoinette, wife of the French king Louis XVI. In spite of its namesake, Marietta thrived. The founders were made of stern genetics, and they had among their group the famed Revolutionary general Rufus Putnam, who was respected by both the immigrants and the native populace. Though General Putnam had died before 1838, Sarah Cutler Dawes remembered the old commander from her early years, and named her second son Rufus Dawes.1

Rufus and his siblings spent many days at their uncle’s farm, located six miles south of Marietta. “Here on the old Cutler place,” wrote one who remembered, “during the days of the Mexican War, frequently could be seen a group of four children, two boys and two girls, naming their pets after war heroes and playing bivouac and field.” The children were Rufus, his brother Ephraim, and his sisters Lucy and Sarah Jane.2

The Mexican War was anathema to the Dawes family, who were abolitionists. Since Marietta was just across the river from what was then western Virginia, many escaping that institution forded the river to Marietta, and received help from the citizens there. Rufus grew up understanding the evils of slavery, and from a young age was determined to defend the oppressed.3

Rufus Dawes attended Marietta College, graduating from there in 1860. He excelled in sports and scholarship. He also was recognized as a leader. During class one day, he learned that a bully had jumped on the back of another student and forced him to carry him up four flights of stairs to their dormitory. Dawes immediately sought the perpetrator, jumped on his back, and ordered him to do exactly what he had done to the oppressed student. “It was needless to say the punishment was effective,” recalled one of the students.4

In 1855, Henry and Sarah Dawes moved to Wisconsin, one of the newest states to emerge from the original Northwest Territory. Having achieved statehood just before Rufus turned ten years old in May 1848, Wisconsin offered inexpensive land and education. Rufus and his younger brother, Ephraim, traveled there with their parents. Alternating between Marietta College and his new home, Rufus was busy traveling between the two states. He also attended the newly established University of Wisconsin. He only completed a few classes when war exploded upon the nation in 1861.5

Upon hearing of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Rufus hurried to enlist. Living at that time in Juneau County, just northwest of Madison, Dawes signed up with the 6th Wisconsin – then only a three-month regiment. He enlisted as a private, but soon raised a company; he was elected captain of Company K. The regiment was officially mustered in August 1861.6

The 6th Wisconsin’s first battle occurred at the Rappahannock in August 1862. They continued to fight in all the major battles of the Civil War through 1864: Gainesville, Second Manassas, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Mine Run, The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Bethesda Church, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. During their three-year’s service in the war, the 6th lost 60% of their men to death and wounds. Dawes was “with them in every fight, yet never received the slightest wound, nor was in the hospital on account of sickness.”7

Dawes was soon promoted to major in 1862, to lieutenant-colonel in early 1863, full colonel in 1864, and retired as a brevet brigadier general in early 1865. He was a regimental commander at age 24 at Gettysburg – commemorating his 25th birthday as Lee’s army vacated the Pennsylvania town. He had “ a keen insight into whatever situation confronted him.” Another remembered that “he had a genius in handling men.”8

One instance that showed his talent for leadership was the famous “Whiskey & Quinine Order”. Quinine, which staved off malaria – an omnipresent threat when engaged in battles in the South, was available but bitter, and strongly disliked by the soldiers. In order to get them to ingest it, Dawes mixed it with the daily allowance of whiskey – which the soldiers often drank to excess. He decided that “every allowance of whiskey was mixed with one of quinine.” The effect was “a tonic” to the men, and kept them healthy while others suffered from, and sometimes succumbed to, the dreaded malaria.9

Dawes was never considered a martinet, and was beloved by his men. He possessed “the quiet word of encouragement, the helping hand, the arm raised to defend the weak”. He was also one who led from the front, never expecting his men to fight where he did not go first himself.10

He would prove that leadership skill with exactness at Gettysburg.

The 6th Wisconsin was part of the famed Iron Brigade. When they arrived at Gettysburg’s western fringe of town, Dawes and his men, the last of the brigade to arrive, were held in reserve on McPherson’s Ridge. Ordered to fight at any moment, Dawes had his regiment aligned and prepared. They saw a body wrapped in a blanket, carried from the field. It was their former commander and recent wing commander, General John Reynolds – but they did not realize it was him at the time. The new commander on the field, Abner Doubleday, rescinded the order to engage that Reynolds had given them. Stuck in the low ground between Seminary and McPherson’s Ridges, with Confederate bullets zipping around them, Dawes ordered his men at the double quick to the Chambersburg Pike.11

They would soon be hotly engaged in one of Gettysburg’s famous fights.

As the 6th Wisconsin advanced to the Chambersburg Pike, General Joe Davis’s Mississippi Brigade also advanced from the west to the same spot. The Mississippi men fired upon the Wisconsin men, which Dawes described as “terribly destructive”. The 6th pushed relentlessly on, charging into the men in butternut. Davis’s men retreated into the unfinished railroad cut.12

As the 6th Wisconsin pressed onward, there were three New York regiments in the vicinity, part of Lysander Cutler’s Brigade. Two of them, the 95th New York and the 14th Brooklyn, fell in line with the Wisconsin men, forming an extended line on their left flank. They fired on the Southern troops, who descended into the unfinished railroad cut. One of the New York men said that the arrival of the Wisconsin regiment “caused our hearts to beat fast with joy and thankfulness.” Dawes and his men had arrived at precisely the right time.13

Dawes had lost his horse in the charge, as the mare was shot in the chest. He continued, unflinching, on foot. As the blue line rushed to the cut, firing upon the beleaguered Confederates, the fight soon came to an end, with Dawes demanding the surrender of the Mississippi men. He asked one of the officers, “Where is the colonel of this regiment?” The officer, a major, ignorantly replied, “Who are you?” Dawes tersely answered that he was the commander of the regiment that had just bested them, and that they had better surrender or be shot. The major immediately gave Dawes his sword. In all, seven swords were handed to him that morning. They captured the 2nd Mississippi’s battle flag, and about 250 prisoners.14

The day, however, was not finished. The 6th Wisconsin remained deployed on the Chambersburg Pike, along with Cutler’s New Yorkers.

The upper echelons of Union leadership did not fare well at Gettysburg’s first day, after the death of General Reynolds. Abner Doubleday and Oliver Howard, both ardent Unionists but mediocre commanders, did not successfully hold the ground during the afternoon of July 1. The Union troops, with the Iron Brigade among them, gave up ground to overwhelming troops, from McPherson’s Ridge to Seminary Ridge, and then had to retreat through town by late afternoon. Both sides incurred heavy losses.

As Dawes led his regiment through Gettysburg, they found themselves in another fight near the intersection of Chambersburg and Washington Streets. Returning fire to the advancing Confederates, Dawes led his men up Washington Street to Cemetery Hill, where they were elated to see Union flags flying resolutely on that high position. They dropped, exhausted, among the stones of Evergreen Cemetery.15

Not all of the men from Juneau County made it to the hill that day. Thirty had been killed and 116 were wounded. Twenty-two were missing. The total losses for that day were 168, over a third of the regiment. They were proud of their accomplishment in the railroad cut. Dawes later exulted, “ t is due to the 6th Wisconsin Regiment for me to say that the regiment led the charge and by its dash forward substantially accomplished the results.” The New York troops had definitely helped, but the 6th Wisconsin had carried the fight to its victory – one of the only Union wins of the day.16

The Wisconsin men, along with the rest of the survivors of the Iron Brigade, spent July 2 and 3 on Culp’s Hill, defending that Union citadel. They aided Greene’s Brigade in the repulse of Johnson’s Division during the evening of July 2. After Gettysburg, neither Meade nor Lee, the army commanders, engaged the men in a decisive battle for the remainder of 1863, although skirmishes and smaller engagements occurred at the Mine Run Campaign. The next decisive battle came in 1864, with Ulysses S. Grant placed in charge of all Union armies. He decided to fight with General Meade, understanding that General Lee was the one to defeat. These clusters of engagements, all devastating to the men of both sides, included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. The men of the 6th Wisconsin were part of them all. Finally, in August 1864, their three-year enlistments were at an end. They were able to go home.17

While Rufus Dawes had commanded the 6th Wisconsin, he nevertheless called Ohio his permanent home. He married Mary Beman Gates, a girl he had met before the war in Marietta, on January 18, 1864 while on leave. The couple settled in Marietta. Six children were born to the couple: Charles, Beman, Henry, Rufus Jr., and two daughters, Mary Frances and Elizabeth.18

Rufus Dawes, brevetted to the rank of brigadier general in 1865, spent his post-war years as a trustee of Marietta College. He was eager to work with the youth, hoping to encourage them to pursue lives of peace and prosperity. He was elected to Congress in 1880 and served for one term. During the McKinley Administration he was the Ambassador to Persia.19

Dawes wrote a memoir, entitled Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers . It was published in 1875. He kept up a robust correspondence with men from his regiment and the famous Iron Brigade – and with those whom he fought at Gettysburg, mostly veterans of the 2nd Mississippi.

In 1889, Dawes began to weaken as the years of war finally played havoc with his physical abilities. He ailed for a full decade. He weakened significantly by the last year of the 19th century, and died on August 1, 1899 in Marietta. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery, with military honors.20

Dawes’s work with the next generation saw fruition, and the success included that of his own children. His son, Charles, became Vice-President of the United States under Calvin Coolidge in 1924. His son Beman was a U.S. Congressman.21

As a Congressman years earlier, General Dawes was “one of the best and most effective debaters.” On the field he was “a favorite with the men.” A true defender, of his nation to the weakest of its citizens, Rufus Dawes, named for another great general, became equally great in following that leadership that he learned as a youth in Marietta. He remains, one hundred and sixty years later, one of Gettysburg’s finest soldiers.22

The upper echelons of Union leadership did not fare well at Gettysburg’s first day, after the death of General Reynolds. Abner Doubleday and Oliver Howard, both ardent Unionists but mediocre commanders, did not successfully hold the ground during the afternoon of July 1. The Union troops, with the Iron Brigade among them, gave up ground to overwhelming troops, from McPherson’s Ridge to Seminary Ridge, and then had to retreat through town by late afternoon. Both sides incurred heavy losses.

As Dawes led his regiment through Gettysburg, they found themselves in another fight near the intersection of Chambersburg and Washington Streets. Returning fire to the advancing Confederates, Dawes led his men up Washington Street to Cemetery Hill, where they were elated to see Union flags flying resolutely on that high position. They dropped, exhausted, among the stones of Evergreen Cemetery.15

Not all of the men from Juneau County made it to the hill that day. Thirty had been killed and 116 were wounded. Twenty-two were missing. The total losses for that day were 168, over a third of the regiment. They were proud of their accomplishment in the railroad cut. Dawes later exulted, “ t is due to the 6th Wisconsin Regiment for me to say that the regiment led the charge and by its dash forward substantially accomplished the results.” The New York troops had definitely helped, but the 6th Wisconsin had carried the fight to its victory – one of the only Union wins of the day.16

The Wisconsin men, along with the rest of the survivors of the Iron Brigade, spent July 2 and 3 on Culp’s Hill, defending that Union citadel. They aided Greene’s Brigade in the repulse of Johnson’s Division during the evening of July 2. After Gettysburg, neither Meade nor Lee, the army commanders, engaged the men in a decisive battle for the remainder of 1863, although skirmishes and smaller engagements occurred at the Mine Run Campaign. The next decisive battle came in 1864, with Ulysses S. Grant placed in charge of all Union armies. He decided to fight with General Meade, understanding that General Lee was the one to defeat. These clusters of engagements, all devastating to the men of both sides, included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. The men of the 6th Wisconsin were part of them all. Finally, in August 1864, their three-year enlistments were at an end. They were able to go home.17

While Rufus Dawes had commanded the 6th Wisconsin, he nevertheless called Ohio his permanent home. He married Mary Beman Gates, a girl he had met before the war in Marietta, on January 18, 1864 while on leave. The couple settled in Marietta. Six children were born to the couple: Charles, Beman, Henry, Rufus Jr., and two daughters, Mary Frances and Elizabeth.18

Rufus Dawes, brevetted to the rank of brigadier general in 1865, spent his post-war years as a trustee of Marietta College. He was eager to work with the youth, hoping to encourage them to pursue lives of peace and prosperity. He was elected to Congress in 1880 and served for one term. During the McKinley Administration he was the Ambassador to Persia.19

Dawes wrote a memoir, entitled Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers . It was published in 1875. He kept up a robust correspondence with men from his regiment and the famous Iron Brigade – and with those whom he fought at Gettysburg, mostly veterans of the 2nd Mississippi.

In 1889, Dawes began to weaken as the years of war finally played havoc with his physical abilities. He ailed for a full decade. He weakened significantly by the last year of the 19th century, and died on August 1, 1899 in Marietta. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery, with military honors.20

Dawes’s work with the next generation saw fruition, and the success included that of his own children. His son, Charles, became Vice-President of the United States under Calvin Coolidge in 1924. His son Beman was a U.S. Congressman.21

As a Congressman years earlier, General Dawes was “one of the best and most effective debaters.” On the field he was “a favorite with the men.” A true defender, of his nation to the weakest of its citizens, Rufus Dawes, named for another great general, became equally great in following that leadership that he learned as a youth in Marietta. He remains, one hundred and sixty years later, one of Gettysburg’s finest soldiers.22

The 6th Wisconsin Memorial

The Railroad Cut, Gettysburg

Sources: The 6th Wisconsin Memorial, Gettysburg, PA. Ancestry.com/Rufus Dawes Family Tree. The Cutler Memorial Genealogical History, found on Ancestry.com. The Marietta Daily Leader, 3 August, 1899 (Dawes Obituary). McCullough, David. The Pioneers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Shue, Richard S. Morning at Willoughby Run. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1998.

End Notes:

1. McCullough, p. 219.

2. Marietta Daily Reader, 3 Aug., 1899.

3. McCullough, p. 220.

4. The Marietta Daily Reader, 3 Aug., 1899.

5. Dawes Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

6. Ibid.

7. Cutler Memorial Genealogical History, p. 118.

8. The Marietta Daily Leader, 3 Aug., 1899.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Pfanz, p. 102. Shue, pp. 131, 151.

12. Pfanz, p. 107.

13. Shue, pp. 159, 161. Dawes and Cutler are distantly related, as Dawes’s mother was a Cutler.

14. Pfanz p. 112. Shue, pp. 164-165. Numbers vary, the ones listed are Dawes’s. The horse, who was as hardy as her owner, survived the battle and the war.

15. Pfanz, p. 330.

16. The 6th Wisconsin Memorial, Gettysburg. Pfanz, p. 113.

17. The 6th Wisconsin Memorial, Gettysburg.

18. Cutler Memorial Genealogical History, p. 118.

19. The Marietta Daily Leader, 3 Aug., 1899.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

Gettysburg, PA

The Gettysburg Experience, P.O. Box 4271 Gettysburg PA 17325 Phone 717.359.0776

© 2008 - 2024 Princess Publications, Inc.

Home

| Maps

| Directions

| Event Calendar

| Contact

| Advertisers

| Advertise with Us