(Library of Congress)

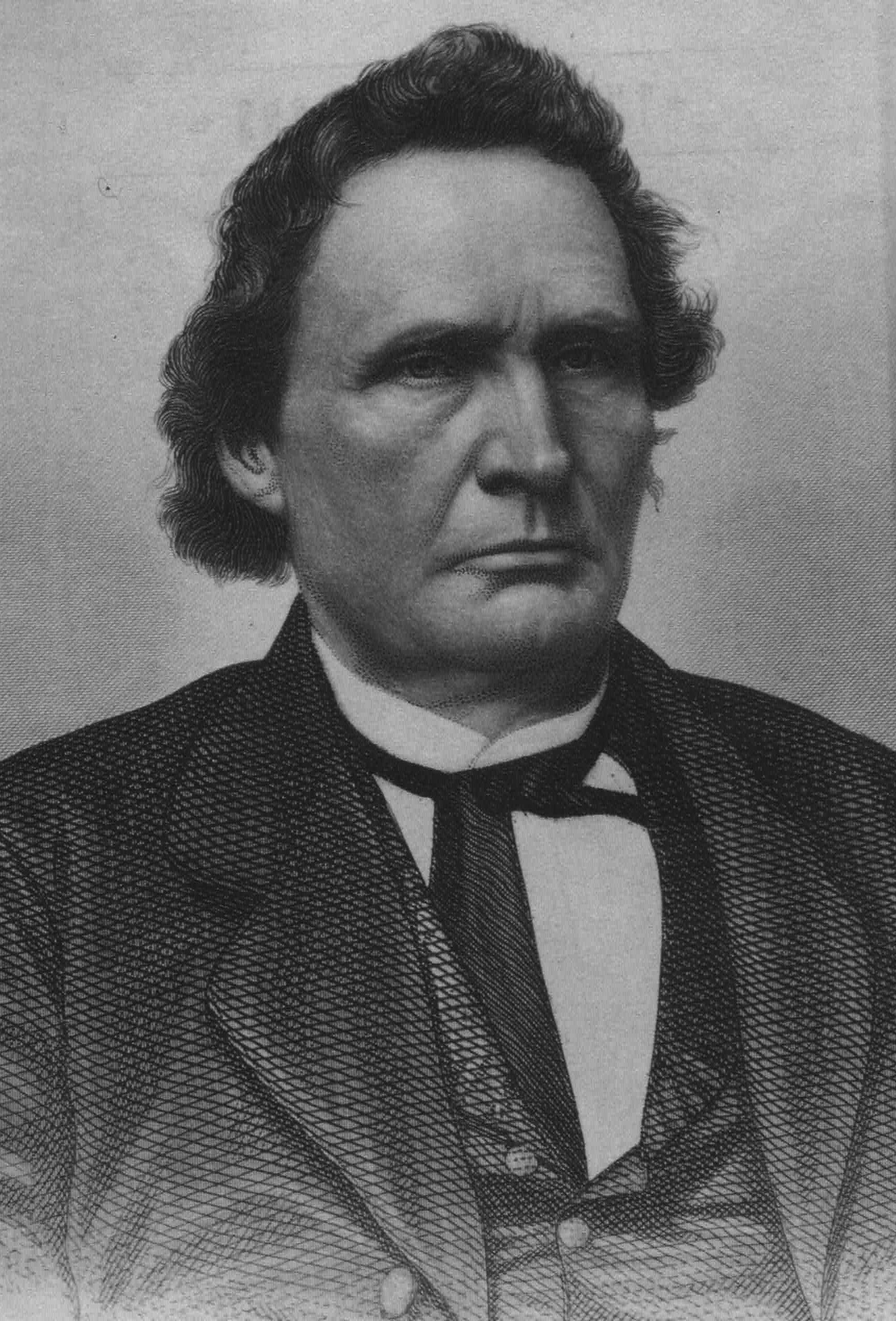

April 4 marks the 229th anniversary of the birth of one of the nation’s most noteworthy defenders of the defenseless in the 19th century.

Thaddeus Stevens, born in 1792 in Danville, Vermont, is only surpassed in history by Abraham Lincoln for his unswerving dedication for liberty for all Americans.1

The second of four brothers born to Joshua and Sarah Stevens, Thaddeus was sickly and lame as a child. He walked with a limp all his life due to a club foot. Since he was unable to thrive out of doors, Thaddeus studied and developed his mind. During Thaddeus’s youth, his father abandoned the family, leaving Sarah to raise the four sons alone. She doted on Thaddeus; because he was a cripple, she encouraged his scholarly pursuits. He was grateful for her influence all his life.2

Graduating from Dartmouth College in 1814, Stevens moved to York, Pennsylvania, where he studied law and taught school. He passed the bar in Bel Air, Maryland in 1815; he then traveled to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania where he set up a law practice in 1816.3

There were several lawyers in the recently established crossroads town, and Stevens’s beginning practice languished. After a year with little progress, he was in the process of deciding to relocate when a grisly murder was committed near Gettysburg. James Hunter, a farmhand, killed Henry Heagy, an associate, with a scythe on June 23, 1817. The crime was so brutal and seemingly unprovoked – and no established attorney in Adams County wanted to touch it.4

Thaddeus agreed to defend the accused murderer.

Thaddeus used, to a brilliant degree, the insanity defense for his client – the first time that such a defense was used in Pennsylvania. The jury did not agree with Thaddeus; his client was found guilty of murder and executed. However, his amazing oratory had won Thaddeus Stevens much publicity, and he remained in Gettysburg, practicing law until he moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1842. Stevens maintained ties with many of his acquaintances in Gettysburg, often aiding the next generation in the practice of law. One of his notable students was future judge and attorney David Wills. Stevens also enjoyed a long friendship with Congressman and historian Edward McPherson. McPherson said of Stevens, “His worst enemy never charged him with uttering a falsehood. His word was as good as his bond.”5

The road to politics was a natural one for Stevens, who was elected to the state legislature in 1838 – about the same time Abraham Lincoln ventured toward statesmanhood. He was elected to Congress in 1848 and 1850 as a Whig. He retired in 1853, but reentered the arena as a Republican in 1858. Considered one of the leaders of the Radical Republicans, Stevens was indeed unyielding in his determination to end slavery and give citizenship to all Americans. His rhetorical powers and his ardent defense of the poor and defenseless earned him the nickname of “The Great Commoner”.6

Thaddeus Stevens never married, but was cared for by a devoted woman for twenty-five years. Lydia Hamilton Smith, a respected widow of mixed race and native of Adams County, served as Stevens’s housekeeper and companion in Lancaster. Although there has been considerable innuendo that their relationship was one of common-law marriage, no concrete evidence has ever been fully established. He deeply respected her, however. Lydia’s influence helped spur Stevens to see to the eradication of slavery.7

Stevens often employed fiery arguments to make his point regarding the hypocrisy of slavery in the United States. He felt that President Lincoln did not do enough – although by the time of Lincoln’s reelection, Stevens was on board with the President.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in January 1865, made permanent Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – and widened the promise to free all those in forced servitude in the United States. The amendment was ratified later that year. Stevens then worked to bring citizenship to the freed slaves, which ultimately was ratified in the 14th and 15th Amendments. The 14th Amendment states that all persons born in the United States are citizens of the nation. The 15th Amendment declares that no one will be exempt from citizenship based on their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Sadly, Thaddeus Stevens did not live to see the latter two amendments passed and ratified.8

The President who followed Lincoln proved to be an arch enemy of Thaddeus Stevens. The powerful Congressman hated Andrew Johnson and was behind the orchestration of his impeachment in 1868. The first President to be impeached, Johnson was acquitted, much to the chagrin of Stevens, who was by this time seriously ill.9

It is likely that Stevens, who had been in precarious health for most of his life, suffered from stomach cancer. By 1868, he grew very pale, weak, and had trouble eating – which in the nineteenth century was called dyspepsia. Too weak to travel home to Lancaster, he retired to his bed in Washington, where Mrs. Smith took care of him. He died at midnight between August 11 and August 12, 1868. He was 76 years old.10

Thaddeus Stevens was the third statesman to lie in state at the Capitol Rotunda (the first two were Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln). He was buried in Lancaster.11

Part of his will, which included Mrs. Smith and his namesake nephew, directed the establishment of an orphanage for children of any color who needed the facility.12

Thaddeus Stevens remains a controversial figure for his fiery determination and unyielding politics. He pushed relentlessly toward an end that was sorely needed in America.

While his pursuits took him to the world stage, Thaddeus Stevens, born a New Englander, considered Pennsylvania his adopted home. His star began to rise at a place called Gettysburg – and it maintains its luster well over a century later.

Thaddeus Stevens, born in 1792 in Danville, Vermont, is only surpassed in history by Abraham Lincoln for his unswerving dedication for liberty for all Americans.1

The second of four brothers born to Joshua and Sarah Stevens, Thaddeus was sickly and lame as a child. He walked with a limp all his life due to a club foot. Since he was unable to thrive out of doors, Thaddeus studied and developed his mind. During Thaddeus’s youth, his father abandoned the family, leaving Sarah to raise the four sons alone. She doted on Thaddeus; because he was a cripple, she encouraged his scholarly pursuits. He was grateful for her influence all his life.2

Graduating from Dartmouth College in 1814, Stevens moved to York, Pennsylvania, where he studied law and taught school. He passed the bar in Bel Air, Maryland in 1815; he then traveled to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania where he set up a law practice in 1816.3

There were several lawyers in the recently established crossroads town, and Stevens’s beginning practice languished. After a year with little progress, he was in the process of deciding to relocate when a grisly murder was committed near Gettysburg. James Hunter, a farmhand, killed Henry Heagy, an associate, with a scythe on June 23, 1817. The crime was so brutal and seemingly unprovoked – and no established attorney in Adams County wanted to touch it.4

Thaddeus agreed to defend the accused murderer.

Thaddeus used, to a brilliant degree, the insanity defense for his client – the first time that such a defense was used in Pennsylvania. The jury did not agree with Thaddeus; his client was found guilty of murder and executed. However, his amazing oratory had won Thaddeus Stevens much publicity, and he remained in Gettysburg, practicing law until he moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1842. Stevens maintained ties with many of his acquaintances in Gettysburg, often aiding the next generation in the practice of law. One of his notable students was future judge and attorney David Wills. Stevens also enjoyed a long friendship with Congressman and historian Edward McPherson. McPherson said of Stevens, “His worst enemy never charged him with uttering a falsehood. His word was as good as his bond.”5

The road to politics was a natural one for Stevens, who was elected to the state legislature in 1838 – about the same time Abraham Lincoln ventured toward statesmanhood. He was elected to Congress in 1848 and 1850 as a Whig. He retired in 1853, but reentered the arena as a Republican in 1858. Considered one of the leaders of the Radical Republicans, Stevens was indeed unyielding in his determination to end slavery and give citizenship to all Americans. His rhetorical powers and his ardent defense of the poor and defenseless earned him the nickname of “The Great Commoner”.6

Thaddeus Stevens never married, but was cared for by a devoted woman for twenty-five years. Lydia Hamilton Smith, a respected widow of mixed race and native of Adams County, served as Stevens’s housekeeper and companion in Lancaster. Although there has been considerable innuendo that their relationship was one of common-law marriage, no concrete evidence has ever been fully established. He deeply respected her, however. Lydia’s influence helped spur Stevens to see to the eradication of slavery.7

Stevens often employed fiery arguments to make his point regarding the hypocrisy of slavery in the United States. He felt that President Lincoln did not do enough – although by the time of Lincoln’s reelection, Stevens was on board with the President.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in January 1865, made permanent Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – and widened the promise to free all those in forced servitude in the United States. The amendment was ratified later that year. Stevens then worked to bring citizenship to the freed slaves, which ultimately was ratified in the 14th and 15th Amendments. The 14th Amendment states that all persons born in the United States are citizens of the nation. The 15th Amendment declares that no one will be exempt from citizenship based on their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Sadly, Thaddeus Stevens did not live to see the latter two amendments passed and ratified.8

The President who followed Lincoln proved to be an arch enemy of Thaddeus Stevens. The powerful Congressman hated Andrew Johnson and was behind the orchestration of his impeachment in 1868. The first President to be impeached, Johnson was acquitted, much to the chagrin of Stevens, who was by this time seriously ill.9

It is likely that Stevens, who had been in precarious health for most of his life, suffered from stomach cancer. By 1868, he grew very pale, weak, and had trouble eating – which in the nineteenth century was called dyspepsia. Too weak to travel home to Lancaster, he retired to his bed in Washington, where Mrs. Smith took care of him. He died at midnight between August 11 and August 12, 1868. He was 76 years old.10

Thaddeus Stevens was the third statesman to lie in state at the Capitol Rotunda (the first two were Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln). He was buried in Lancaster.11

Part of his will, which included Mrs. Smith and his namesake nephew, directed the establishment of an orphanage for children of any color who needed the facility.12

Thaddeus Stevens remains a controversial figure for his fiery determination and unyielding politics. He pushed relentlessly toward an end that was sorely needed in America.

While his pursuits took him to the world stage, Thaddeus Stevens, born a New Englander, considered Pennsylvania his adopted home. His star began to rise at a place called Gettysburg – and it maintains its luster well over a century later.

Sources: The Constitution of the United States. Philadelphia, PA: The National Constitution Center, 2003 (first printed in 1787). Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. V. New York: Private Publisher, 1889 (accessed through Ancestry.com.). Hamilton Family File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). The Gettysburg Times, “Thaddeus Stevens’ First Case”, 8 Feb., 1958. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 28 July 1911. Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. New York: Galahad Books, 1993 (Reprint, first published in 1935). Thaddeus Stevens Family History, Ancestry.com. Trefousse, Hans L. Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth Century Egalitarian. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997. Historic newspapers accessed through newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Thaddeus Stevens Family History, Ancestry.com. There is some discrepancy as to the year of his birth. Some historians maintain he was born in 1793.

2. Drake, p. 677. Trefousse, p. 2.

3. Drake, p. 678.

4. The Gettysburg Times, 8 Feb., 1958.

5. Trefousse, p. 8.

6. Drake, p. 677.

7. Hamilton Family File, ACHS. Trefousse, p. 69-70. Lydia Hamilton’s father was Enoch Hamilton, a white farmer. He was married and had a young family when he fathered Lydia by his mistress, a woman of ethnic heritage.

8. U.S. Constitution, p. 27.

9. Sandburg, p. 465. Trefousse, p. 229-230.

10. Trefousse, p. 240.

11. Pittsburgh Gazette, 28 July, 1911.

12. Drake, p. 678.