The Day Before the Battle

by Diana Loski

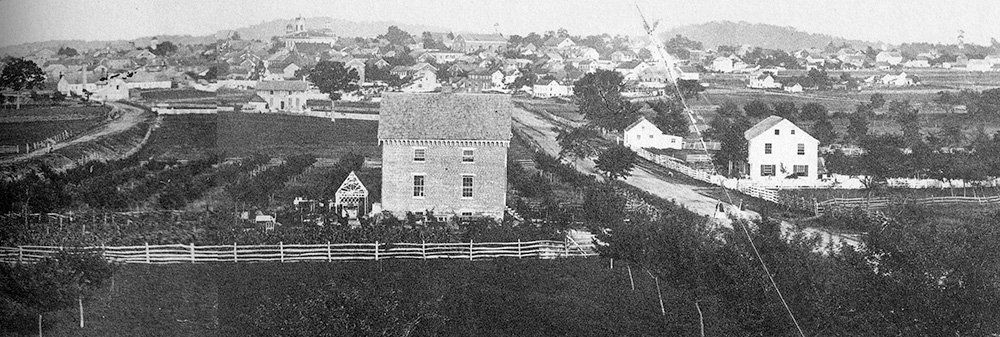

Gettysburg, 1863

(Adams County Historical Society)

July 1 through July 3 of the summer of 1863 are well documented in history as the fateful days that comprised the famous Battle of Gettysburg.

General Lee had not actually wanted to fight at Gettysburg. His objective was Washington, D.C. He had planned to invade a northern city, perhaps Harrisburg, cause the Union army to head there to their defense, and Lee could then lead his army by another route to the Union capital. The Battle of Gettysburg stopped that plan.

The day before the battle has far less documentation. Yet, a glimpse into that day gives additional insight into the setting of the stage of that most pivotal event.

June 30, 1863 was a Tuesday. The previous days had been hot, humid, and with on-and-off rain. As a result, the air was heavy; the roads and surrounding fields were muddy, some excessively so.

By June 30, both Lee and Meade knew that a battle was imminent. Though Lee had believed he had invaded Pennsylvania without the Union army’s awareness, Meade, the new Union general of the Army of the Potomac, knew exactly where Lee’s troops were. Brigadier General John Buford, who commanded a division of Union cavalry, had apprised him with precise information.

Lee, meanwhile, had depended upon Major General Jeb Stuart, commander of the Confederate Division of Cavalry, to do the same. At 10 a.m. on the morning of June 30, General Stuart attempted to reach Lee, who was in the vicinity of Cashtown, a village west of Gettysburg. Stuart met resistance with Union cavalry at the rarely remembered engagement known as the Battle of Hanover.

Hanover, Pennsylvania is located about fourteen miles southeast of Gettysburg. On the western outskirts of the town, Stuart clashed with Brigadier General Elon Farnsworth’s horse soldiers. Farnsworth was soon supported by Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer and his Michigan troops. They formed an effective barricade, keeping Stuart from his objective. Additionally, Stuart had with him over two dozen wagons, filled with needed supplies that he intended for Lee’s army. Stuart’s unwillingness to part with them sealed the Confederate inability to break through the Union cavalry. Lee, in turn, had no idea where Stuart was and why he had not reported. Without Stuart, General Lee was not certain of the Union position and how many Union troops were in the vicinity. When the spy, Henry Harrison, gave that information to the general, Lee was not certain he could trust Longstreet’s agent.1

General Lee was not in good health – he was suffering from heart disease and had two sprained wrists after his horse, Traveller, had recently bolted and thrown him. His staff officers noticed that Lee seemed “visibly disturbed” and feeling “gloomy”. No doubt the uncertainty of the situation bothered him.2

In town, the civilians were equally agitated when they learned that more Confederate troops were nearby. On the previous Friday, June 26, a division of Southern infantry (accompanied by some cavalry) invaded Gettysburg, demanding money and supplies, and helped themselves to civilian stores and horses. While some behaved well, others did not, and the thought of more invaders panicked the townspeople. Shortly before noon on June 30, two brigades of Buford’s cavalry – and Buford himself – entered the town, to the delight and relief of the people.

“They passed northwardly along Washington Street,” wrote Tillie Pierce, a fifteen-year-old who lived on Baltimore Street, “turned toward the west on reaching Chambersburg Street and passed out in the direction of the Theological Seminary.”3

About a dozen of the town’s young ladies who lived in the neighborhood hurried to the corner of Washington and High Streets with water, food, and songs. The men in blue greatly appreciated their kindness, after having served so long in hostile territory. Some of the singing repertoire included Our Union Forever, Tramp, Tramp, Tramp

, Battle Cry of Freedom, John Brown’s Body, and When This Cruel War is Over.4

“They were Union soldiers, and that was enough for me,” Tillie Pierce recalled, “for then I knew we had protection.”5

Brigadier General James J. Pettigrew, a Confederate officer in charge of North Carolina troops, also saw Buford’s cavalry. Formerly deployed in his home state of North Carolina until May 1863, Pettigrew was new to the Army of Northern Virginia. Having planned on entering Gettysburg for needed supplies that day, Pettigrew quickly withdrew and reported the sighting to his division commander, Major General Harry Heth 6

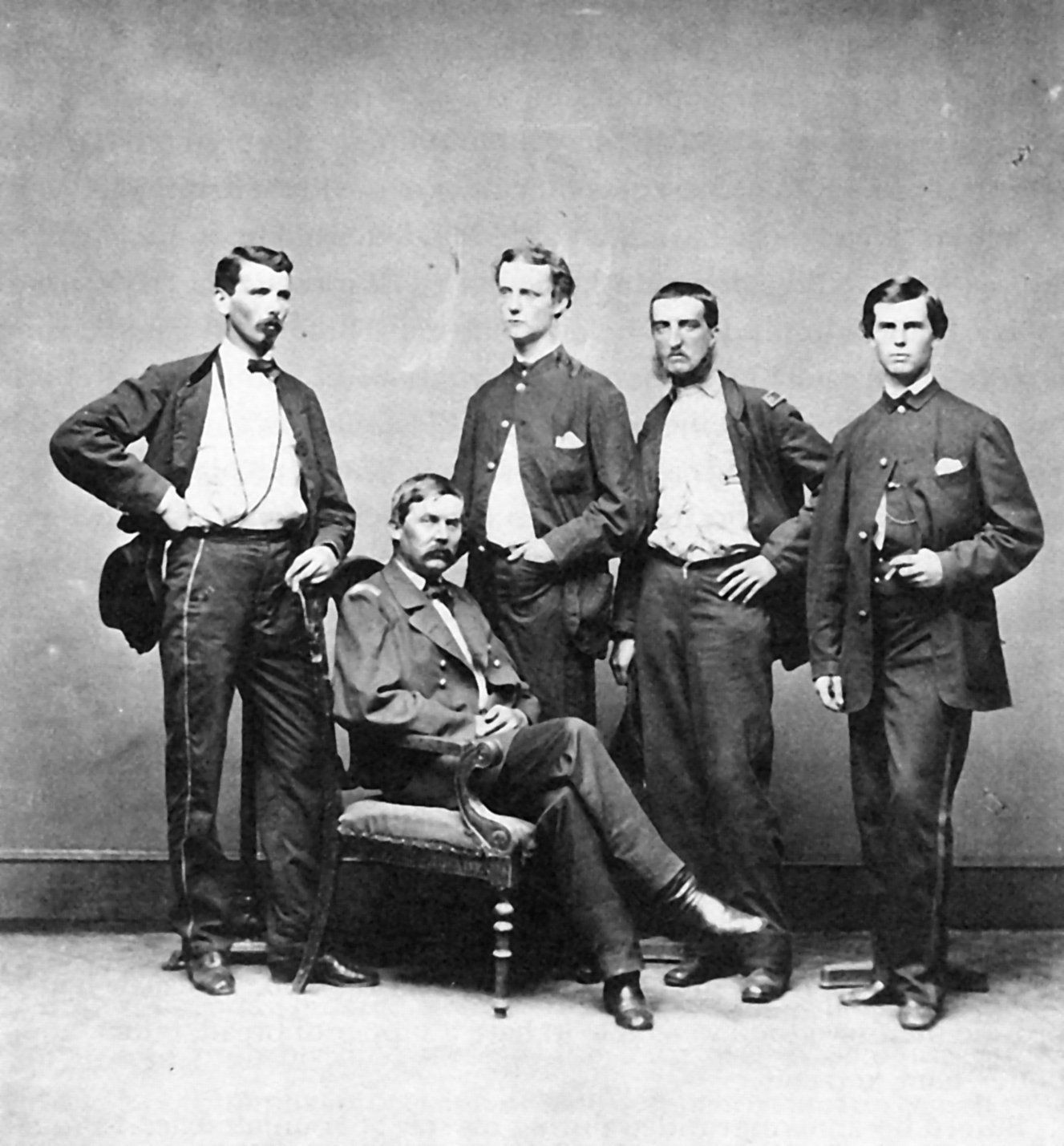

General John Buford (seated) and staff, 1863

(Library of Congress)

Heth and his superior, Lt. General A.P. Hill, the commander of the recently created Confederate Third Corps, believed this newly acquired general was not sure who were part of the regular Union army and who were the home guard – local militia who were no match for Lee’s veterans. They dismissed Pettigrew’s claims. When Pettigrew was backed by Lt. Louis Young, formerly on General Pender’s staff, Heth and Hill ignored him as well.7

Farther north, the Confederate Second Corps had recently arrived in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. After indulging in a sizable stash of food and spirits at the Carlisle Barracks, many of the malnourished soldiers became inebriated. Other members of the corps were spread out from the village Heidlersburg northeast of Gettysburg, to the hamlet of Scotland near Chambersburg. When the new corps commander, Lt. General Richard Ewell, received orders to concentrate at Gettysburg, the men in gray prepared to congregate and head south.8

Bringing up the rear of Lee’s army was the division led by George Pickett, who was around Chambersburg – 24 miles to the west. His troops were the last of the Confederate infantry to arrive at Gettysburg, too late in the afternoon of July 2 to be able to go into battle.9

By the evening, both Lee and Meade suspected that a battle was unavoidable. While Lee pondered what might have happened to Stuart and acquiesced to the information provided by Harrison, Meade had received exact and detailed reports from John Buford. A careful man, Meade had hoped to draw Lee’s army southward into Maryland; he had planned on using the hilly terrain around the meandering Pipe Creek before hearing about the amassing of troops around Gettysburg. He studied his maps, thinking that perhaps Pipe Creek would be a good second place to fall back if needed. He issued a circular, reminding his troops to be alert for orders for a probable conflict at Gettysburg. He remained at his headquarters at Taneytown, Maryland.

Just over the Maryland border, at the Moritz Tavern, the Federal First and Eleventh Corps commanders, Major General John Reynolds and Major General Oliver O. Howard, were enjoying a meal. Reynolds, also consistently updated by Buford, stayed up after Howard left for his headquarters in Emmitsburg. At midnight, he finally fell asleep for a few hours.10

Before June passed into July, both armies were expecting the fight. While still spread out and not all present, they were nevertheless coming to Gettysburg.

While numbers vary, the Union army would have about 95,000 men engaged at Gettysburg. The Confederate army would have about 75,000. The town population at that time numbered about 2,400 – while most of the adult male population was away, fighting the war. Most of them served in a different army and would not be at Gettysburg.11

Because of the continual movement of troops, and because the surviving troops soon vacated Gettysburg after the fight, no one can be sure of the exact number present. As a result, it is impossible to know how many were killed, wounded, captured, and missing at Gettysburg. However, it can be surmised that most likely the bulk of both armies were indeed present at Gettysburg. July 1 was payday for the Federal troops. The Southern troops, malnourished and in great need of supplies, would be where the food was abundant.

Throughout the evening of June 30, some of the civilian populace ventured out to the Lutheran Seminary, bringing food to Buford’s men who were camped there. General Buford stayed in town at the Eagle Hotel, which stood on the corner of Washington and Chambersburg Streets. Gettysburg youth Daniel Skelly noticed the general near the hotel that day. He recalled, “General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me, entirely alone, facing to the west and in profound thought.”12

Buford, the veteran horse soldier, knew what the next day would bring.

It appears that, on the Confederate side, some of the high command did not know. Lieutenant Louis Young, who had seen Buford’s cavalry with Pettigrew that day, later called, “blindness in part seems to have taken over our commanders.” He wrote that this lack of preparation “rendered them unprepared for what was to happen.”

13

While there was no stash of shoes at Gettysburg – Hanover had the shoe factory – the Confederates were as unaware of that fact as they were of the significant Union presence. That evening, Harry Heth reportedly said to General Hill, “If there is no objection, I will take my division to-morrow and go to Gettysburg and get those shoes.” Hill replied to him, “None in the world.”14

The next morning was cloudy and uncomfortably humid as Heth sent his men toward Gettysburg. It was Wednesday, July 1.

Sources: Alleman, Mrs. Tillie Pierce. At Gettysburg: Or What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle . New York: Borland, 1889 (reprinted by The Shriver House Museum, 2015). Civilian Accounts, Daniel Skelly, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee . Vol. 3. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935, 1936. Loski, Diana. Gettysburg Experiences . Gettysburg: Princess Publications, 2002. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Rodgers, Sarah Sites. Ties of the Past: The Gettysburg Diaries of Salome Myers Stewart 1854-1922 . Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1996. Shue, Richard S. Morning at Willoughby Run . Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1998.

End Notes:

1. Coddington, p. 241.

2. Freeman, pp. 62-63.

3. Alleman, p. 28.

4. Rodgers, p. 147.

5. Alleman, p. 29.

6. Loski, p. 122. Shue, p. 35.

7. Pfanz, pp. 27-28.

8. Coddington, pp. 150, 159. Shue, p. 63.

9. Coddington, p. 458.

10. Pfanz, pp. 46-47. Coddington, p. 261.

11. Coddington, pp. 244, 248-249. Company K of the 1st PA Reserves were the exception.

12. Daniel Skelly Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

13. Pfanz, pp. 27-28. Ibid.

Gettysburg, PA