The Last General

by Diana Loski

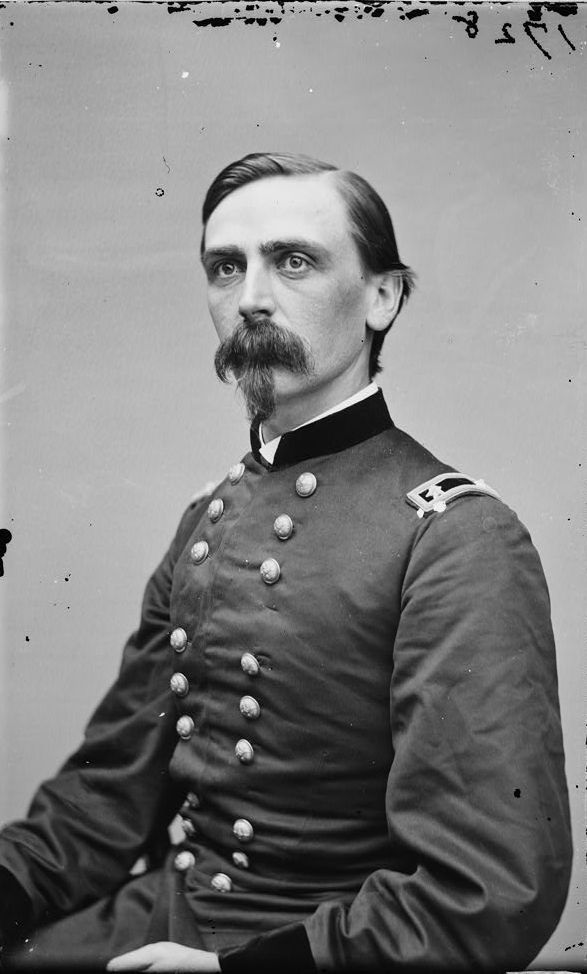

Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames

(Library of Congress)

Adelbert Ames was the son of a sea captain, born in the coastal town of Rockport, Maine on October 31, 1835. He grew up on water as much as on land, and was comfortable on both. He traveled on a clipper with his father, visiting Africa, Europe and the West Indies by the time he was fifteen. By the time he reached twenty years of age, Ames decided that a mariner’s life was not what he preferred. It necessitated exceedingly hard labor, the sea was often perilous, and, being a gentleman, he realized that sailors did not enjoy even a passable reputation. In July 1856, he was accepted at West Point.2

Ames was highly intelligent, decidedly moral, and exceedingly ambitious. Having already seen much of the world as a youth, his aptitude for knowledge acquired by the long voyages in the company of adults gave him an edge with his studies. A fellow cadet said of Ames that “he was about as close an approximation to Sir Galahad as was likely to be found.”3

The clouds of war already existed by 1856 and grew substantially while Ames attended the Point. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabi n caused an uproar. John Brown had caused insurrection and was subsequently hanged for his crime. Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas made headlines with their debates on slavery. When Ames graduated in 1861, war had arrived. He placed fifth in his class, which included men like the stalwart Patrick O’Rorke, who graduated in first place, and the flamboyant George Armstrong Custer, who graduated in last place. Upon graduation these men immediately offered their services, eager to get into the fight.

Ames was given a lieutenancy in the 5th U.S. Artillery and sent to the front. He participated in the Battle of First Manassas, and was one of thousands to be wounded in that conflict. Though his wound bled profusely, Ames refused to leave the field, issuing orders as his boot filled with blood. He finally collapsed and was carried from the field, his tenacity noticed by his superiors.

While recuperating, Ames was ordered to the defenses of Washington. He remained there for the rest of 1861, finally returning to field duty. The Peninsular Campaign – the attempt to take Richmond – ensued, and Ames was again conspicuous in the multitude of battles. He was promoted to the rank of Colonel in the summer of 1862, and given a regiment of new recruits. Because Maine was sparsely populated, most of the regiments from the state had already enlisted. The new regiment, the 20th Maine, offered a mixture of men from various parts of the state. Many were college students, farmers, and laborers who were as excruciatingly independent as they were patriotic.

The initial meeting of Ames and the men of the 20th Maine did not go well. Unused to military protocol, the majority of men did not care for orders, at least orders without a good reason. Ames, the West Point graduate, was incensed at their lackluster behavior. “ This is a hell of a regiment! ” he exclaimed. He then shouted at one of the slouching soldiers, “For God’s sake, draw up your bowels !”4

He was determined to work them so that they would be ready for battle.

Colonel Ames immediately began drilling the regiment, and soon enough ordered a dress parade to note their progress. The men fell out of line, tripped over one another, and all to a tinny, off-key attempt by the regimental band. Ames was aghast. A few weeks later, Ames tried again, and the men again failed miserably. Ames shouted at them that if they couldn’t improve, they should desert and go home. His attitude did not endear him to the men. Tom Chamberlain, the brother of Lt. Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, wrote to his sister that all the men hated Ames, adding, “I swear they will shoot him the first battle we are in.”5

Joshua Chamberlain, however, liked his strict commander. Ames tutored his second in command by night, explaining intricate points of battle maneuvers and militaria. Chamberlain, a professor at Bowdoin College, was an eager pupil.

Although the 20th Maine was present at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, they, inexplicably, did not fight that day. They were engaged at the next one, however, at Fredericksburg. At that battle, the regiment realized Ames’s drilling and teaching had a purpose. Though the Federals lost the battle, most of the men from the 20th Maine had survived.

Due to a problem with a faulty smallpox vaccine in the spring of 1863, many of the men from Maine contracted the disease and therefore were not able to fight at the next battle, which was Chancellorsville. Colonel Ames, however, managed to get into the fight on General Meade’s Fifth Corps staff. His courage was evident, and Meade recommended Ames for promotion. When the Federal army pursued Lee’s men northward into Pennsylvania, General Meade was promoted to army commander. Adelbert Ames also received a promotion to brigade command. He was sent from the Fifth Corps to the Eleventh Corps, and saw the need to command more green troops, many of whom did not speak English. They had recently, and to their shame, been routed at Chancellorsville. The Federal high command hoped that Ames could work them into shape.

Ames’s Brigade found themselves in the thick of the fight at Gettysburg, against a superior Confederate force north of the college on the first of July, 1863. They arrived in the afternoon, hours after the First Corps had been engaged, and were hit by the arrival of Jubal Early's Division. After a time of desperate fighting, General Barlow, the division commander, was desperately wounded. Ames then took command of the division. It would have been fortuitous had General Ames been in charge from the beginning, but politics and government dictated otherwise, and Francis Barlow, who had no military training, was, at age 26, put in charge of the First Division of the Eleventh Corps. Ames was only a year Barlow’s senior, but had West Point experience and great fortitude. By the time he had control of the division, the momentum had been lost and the fate of the Eleventh Corps was sealed. General Ames and his men were forced back with the rest of the Eleventh Corps to Cemetery Hill.

Ames was determined to keep up the fight, and his chance came the next evening with the Confederate attack on the Union right flank, on Cemetery and Culp’s Hills. Ames placed his brigade in a strong defensive position on East Cemetery Hill and fought at the front lines himself, at times in hand-to-hand combat. In spite of the alarming nature of the battle at night, Ames displayed a professional temerity under fire. He was the best kind of man to be associated with,” remarked artillery commander Charles Wainwright, “cool and clear in his own judgment, gentlemanly, without the smallest desire to interfere.”6

After the battle, Ames visited his old regiment, the 20th Maine, who had stalwartly defended Little Round Top and were victorious. General Ames commended them, saying he “was proud of the 20th.” It was a far cry from what he had exclaimed to them nearly a year earlier, admonishing them to desert and go home.7

Many thousands of men and women displayed great bravery during those terrible three days of fighting at Gettysburg. It is easy to miss one of such significance as General Ames. He not only defended the fields north of the college on the first day, and Cemetery Hill on the second day, his prudent training of the 20th Maine, and notably, their commander Joshua Chamberlain, resulted in their brilliant and tenacious hold of Little Round Top, the key to the battlefield and one of the causes of the ultimate Union victory at Gettysburg.

After Gettysburg, the Federal Eleventh and Twelfth Corps were sent west to aid in the fight in Tennessee and Georgia. Ames, too, was transferred to another position. He found himself in division command in the 24th Corps, in the Army of the James in Virginia. The army was commanded by the controversial General Benjamin Butler. Ames, however, liked the commander and the pair got on well.

Ames played a role in the capture of Fort Fisher in North Carolina, displaying his characteristic bravery under fire until the war ended. He was brevetted Major General of Volunteers for his meritorious services during the war. The most grueling fight of his life, however, was yet to come.

Many in the vanquished South had little desire to be united with the ones who defeated them, leading the new political leaders in Washington to create military districts. They needed commanders to fill these new military governments in the Southern states. General Ames, who remained with the U.S. Army, was assigned to work in these military districts. In 1868, while visiting his old commander Benjamin Butler, Ames met Butler’s daughter, Blanche. A courtship ensued and they married in 1870. Six children were born to the couple.8

Ames won a senate seat in Mississippi the same year he was married. He tried tact and kindness with the former Confederates, hosting parties and formal receptions in their attempt to forge friendships. Nothing worked.

Ames was elected governor of Mississippi, demonstrating that enough citizens of the newly reconstructed state liked him enough to vote for him. He served for two years.

Ames’s lieutenant governor, a man of color, was not accepted by the people of Mississippi. Riots ensued and violence against the black populace escalated, sending the former slaves to the governor’s mansion for protection. The violence was so heated, Ames feared for the life of his family and sent Blanche and the children to Massachusetts. He asked urgently for Federal aid, which did not come. He then put down the insurrection and was subsequently threatened with impeachment. He resigned and left Mississippi forever, disgusted with the hatred that poisoned his hopeless efforts.9

After leaving the South, Ames invested in a flour mill company, which took him and his family to Minnesota, New York, and eventually back to New England. They settled in Lowell, Massachusetts.

In 1894, Ames received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courageous acts under fire at First Manassas. In 1898, he offered his services in the Spanish American War, and was accepted. Because of his age, at 58, and due to the short-term war, he was not in the field.

In his waning years, both Ames and his wife remained cheerful and engaged in their community. They spent their winters in Florida to escape the harsh New England temperatures. It was at his Florida beach retreat that General Ames died on April 12, 1933. Neighbors commented that he had “appeared in good health ” the day before his death, and that it had come upon him suddenly.10

His body was taken to the family plot in Lowell, Massachusetts. The military funeral, befitting the old general, was simple as there were few left from the old war to attend. As Taps reverently sounded, he was buried near his father-in-law, Benjamin Butler, who had died forty years earlier.11

Decades later, a senator from Massachusetts wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book, Profiles in Courage. The author, John F. Kennedy, wrote a stinging rebuke of Governor Ames’s fight in Mississippi, and accused the old general of bringing Mississippi to ruin. Ames’s youngest daughter, Blanche, read the book and was incensed by what she considered a slanderous accusation, which was not a true assessment of the situation or her father. She wrote to Senator Kennedy, insisting that he retract what he had written about General Ames. Kennedy told her to write her own views about her father. Blanche did so, wanting the truth to be known, realizing that history would judge her father – and she wanted the judgment to be accurate and fair.12

Her father, another tireless supporter of truth and justice, would have been proud.

Sources: Ames, Blanche. Adelbert Ames: Broken Oaths and Reconstruction in Mississippi . New York: Argosy-Antiquarian Books, 1964. Copy, Maine State Archives, Augusta, Maine. The Bangor Daily News, 14 April, 1933. The Bangor Daily News, 18 April, 1933. Barlow’s (Ames) Division File, Gettysburg National Military Park. Budiansky, Stephen. The Bloody Shirt . New York: Penguin Books, 2008. Kennedy, John F. Profiles in Courage . New York: Harper & Bros., 1956. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill . Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993. Pullen, John. The Twentieth Maine . Dayton, OH: Morningside Press, 1991 (reprint, originally published in 1957). Ellis Spear Diary, copy, GNMP. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.

End Notes:

1. Warner, p. 6. While there is another general considered to be a later survvor, he received an honorary brevet at the end of the war, and was never an acting general in the field. To that end, Ames was the last general, as he was an acting general during the war.

2. Ames, pp. 27-29.

3. Budiansky, p. 65.

4. Pullen, pp. 3, 36.

5. Ibid.

6. Barlow Division File, GNMP. Spear Diary, p.17.

Pfanz, p. 243.

7. Pullen, p. 131.

8. Ames, p. 491. Budiansky, pp. 63, 87.

9. Kennedy, p. 168. Budiansky, p. 188.

10. The Bangor Daily News, 14 April, 1933.

11. The Bangor Daily News, 18 Apr., 1933.

12. Kennedy, p. 169. Ames, p. xii.

Gettysburg, PA