The Lincoln Inaugurals

The Lincoln Inaugurals

by Diana Loski

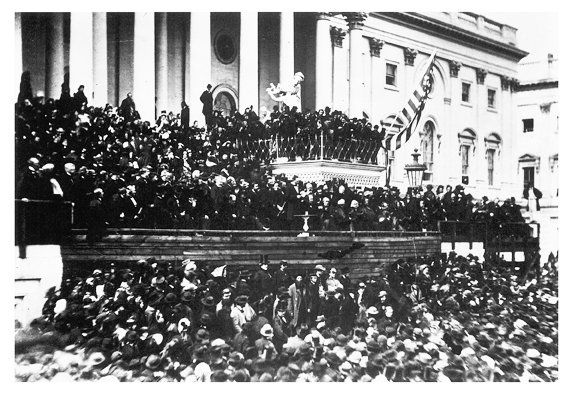

Lincoln's 2nd Inauguration, March 4, 1865

(Library of Congress)

One hundred and sixty years ago, in March 1861, Washington D.C. was greatly excited. With throngs of people in attendance and a strong military presence to prevent turmoil, Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office on a blustery day that threatened rain – and significant foreboding.

Lincoln knew well that the nation was at the breaking point with his election to the White House. He had carefully written his inaugural speech when already seven Southern states had seceded because of his stance against slavery. His trusted friend and bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, remembered, “Lincoln soon began to realize with dismay what was before him.” Lincoln had worked and reworked his inaugural speech before embarking for Washington. On the train, he placed his unfinished speech in a valise, and kept it near him at all times. During one of their stays at a hotel in Harrisburg, Lincoln entrusted the satchel to his son, Robert, who promptly lost it. “I had never seen Mr. Lincoln so annoyed, so much perplexed, and for the time so angry,” Lamon recalled. Lincoln hurried back to the hotel where Robert had nonchalantly handed it off, and after a vigorous search, he and Lamon discovered the missing valise in the baggage room. Lincoln then kept the document on his person until he arrived in the capital.1

The day before his inauguration, Lincoln had William Henry Seward – soon to be the Secretary of State – peruse his speech and offer advice. Seward suggested he make more concessions to the South. Lincoln refused. “No Democratic President ever had to bargain for his right to assume office” one historian wrote. “Lincoln wasn’t going to either.”2

It is important to note that for over three decades the Democratic party wielded great power in Washington. They had a stronghold since the days of Andrew Jackson beginning in early 1829. After serving two terms, Old Hickory was followed by his Vice President, Martin Van Buren. In 1840, Van Buren was so disliked that a Whig and war hero, William Henry Harrison, assumed office. He died within a month of his inauguration, replaced by his Vice President, John Tyler. Although Tyler had run on the Whig platform with Harrison, he was widely known as a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. Like Van Buren, Tyler was wildly unpopular as President and only served one term. He was replaced by James K. Polk, a protégé of Andrew Jackson. The fellow Tennessean was so like his famous predecessor, he was called “Young Hickory”. He too, served one term, dying shortly after leaving office. The Whig party successfully got war hero Zachary Taylor elected, but he only served just over a year, dying of a mysterious illness linked to food poisoning shortly after refusing to comply with Congress’s Fugitive Slave Act bill. He was succeeded by his weak Vice President, Millard Fillmore, who acquiesced to whatever demands the opposing party placed upon his desk. He only finished Taylor’s term. From that point, two more Democratic Presidents served: Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. Interestingly, since Andrew Jackson’s election, no President until Lincoln had been elected to two terms.

In addition to the Democratic stronghold at the Executive Mansion, the party had a strong voice in Congress. In addition to the Northern Democrats, the South added to their population by counting every slave as 3/5 of a person – multiplying their numbers for the House of Representatives. No wonder Lincoln’s election was an upset.

Lincoln understood that he threatened decades of power, wealth, and influence; he knew they would not easily yield it to a prairie lawyer upon whom they looked with aspersions – and who threatened a centuries-old institution that secured not only their wealth, but their power in Washington.

March 4, 1861 fell on a Monday, a pleasant day to start, but the weather later turned cloudy and chilly. Thousands of visitors thronged to see the outgoing and incoming Presidents, who rode together in a carriage to the portico of the unfinished Capitol building.

Buchanan and Lincoln hardly spoke. At one point, Buchanan purportedly mentioned to Lincoln, “If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel in returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.” The nation was in a dangerous place, and the 69-year-old Buchanan also keenly felt it.3

When Lincoln rose amid the wind and cold to give his inaugural address, he was met with little applause. His speech was indeed a peace offering, but he refused to give in to the threats of war and further secession. He did, however, promise not to further interfere with slavery, but only to keep true to the Constitution. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen,” he said, “and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” He reminded those who listened that he was sworn to protect the Constitution of the United States. He ended with a plea: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passions may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” 4

Lincoln then took the oath of office, administered by the aged and sickly Chief Justice Roger Taney.

Untold thousands who did not hear the address waited impatiently for it to appear in print. From New York to Richmond and beyond, crowds thronged the streets for the newspapers as soon as they were available. Many in the South did not sense any conciliation.

The better angels, unfortunately, did not manifest; the war Lincoln had hoped to avert still came.

In the midst of the terrible Civil War, Lincoln won reelection. His second inaugural speech, given on Saturday, March 4, 1865, is considered one of his greatest orations – perhaps only eclipsed by the President’s Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln was not well in the last days of winter that year. He had little sleep each night. He was anxious for the news of the war in its final weeks, and hate mail – along with vindictive attacks from newspapers – poured in. There were also threats against his life. “I know I’m in danger,” he told William H. Seward, “but I am not going to worry about it.” The war, he knew, was coming to an end, he just did not know when that end would come. His second inaugural speech, however, mirrored that hope in a new beginning at the end of the conflict.5

March 4 dawned dark and gloomy, with rain drizzling. Crowds thronged near the Capitol, where Lincoln arrived in his carriage. The streets were “a muddy paste” as women in their crinolines and men in their top hats assembled near the portico.6

Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Unionist, was the new Vice President Elect. Terrified of speaking before such a large assemblage, he had written to Lincoln, asking if he could take the oath of office in Nashville. Lincoln sent him a cable, insisting that he be in Washington.

Johnson was there, and downed at least two glasses of whiskey before his speech, which took place before the President’s. His speech was not memorable, and correspondent Noah Brooks remembered watching the faces of members of the Cabinet and Senators grimacing or writhing in their seats as he spoke. 7

Lincoln, who still felt unwell, listened patiently to the speech that preceded him. Then he rose, and as he approached the platform, the dark, blustery day was interrupted by a burst of sunshine, then “a tremendous shout, prolonged and loud, arose from the surging ocean of humanity.” It was the complete opposite of the welcome he had received four years earlier.8

Lincoln noticed Frederick Douglass in the crowd, and he instantly felt cheered. His speech was, like his first inaugural, carefully written and delivered with exactness.9

The President spoke of the late war, its enormous cost, and the importance of preserving the Union. “Fondly do we hope,” he continued, “fervently do we pray – that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.” He then ended with one of the most enduring passages ever uttered by a President: “With malice toward none, with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and for his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and among all nations.”10

Noah Brooks wrote that, as Lincoln uttered the final paragraph, “one could see moist eyes and even tearful cheeks ” among the crowd. He noted that the speech was “received in the most profound silence.”11

Lincoln then took the oath of office administered by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase.

“Among the memories of a lifetime,” penned Noah Brooks, “doubtless there are none more fondly cherished by those who were so fortunate as to stand near Lincoln at that historic moment.”12

There was at least one in attendance, however, who did not feel the same. His name was John Wilkes Booth. He had, earlier that day, tried to gain access to Lincoln in the Capitol, but had been prevented by police.

“Illuminated by the deceptive brilliance of a March sunburst ,” recalled Noah Brooks about that historic inaugural day, “ Lincoln was already standing in the shadow of death.”13

Lincoln had promised healing to all Americans, North and South, Union and Confederate – a magnanimous and truly merciful plan. It showed him for the humble and kindly human being that he was. The war had taken a heavy toll on him, physically and emotionally, and he was ready for the horror to end.

He could not have known that there was more horror to come.

Six weeks to the day after giving his second inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln was dead, assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. The unfortunate Andrew Johnson, as ill-prepared to serve as Chief Executive as he was in giving speeches, was a poor replacement.

The 16th President’s immortal addresses remain. They provide a glimpse into the mind and heart of a man who stood resolutely for his nation and his principles during excessively difficult times. His words still inspire.

Lincoln knew well that the nation was at the breaking point with his election to the White House. He had carefully written his inaugural speech when already seven Southern states had seceded because of his stance against slavery. His trusted friend and bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, remembered, “Lincoln soon began to realize with dismay what was before him.” Lincoln had worked and reworked his inaugural speech before embarking for Washington. On the train, he placed his unfinished speech in a valise, and kept it near him at all times. During one of their stays at a hotel in Harrisburg, Lincoln entrusted the satchel to his son, Robert, who promptly lost it. “I had never seen Mr. Lincoln so annoyed, so much perplexed, and for the time so angry,” Lamon recalled. Lincoln hurried back to the hotel where Robert had nonchalantly handed it off, and after a vigorous search, he and Lamon discovered the missing valise in the baggage room. Lincoln then kept the document on his person until he arrived in the capital.1

The day before his inauguration, Lincoln had William Henry Seward – soon to be the Secretary of State – peruse his speech and offer advice. Seward suggested he make more concessions to the South. Lincoln refused. “No Democratic President ever had to bargain for his right to assume office” one historian wrote. “Lincoln wasn’t going to either.”2

It is important to note that for over three decades the Democratic party wielded great power in Washington. They had a stronghold since the days of Andrew Jackson beginning in early 1829. After serving two terms, Old Hickory was followed by his Vice President, Martin Van Buren. In 1840, Van Buren was so disliked that a Whig and war hero, William Henry Harrison, assumed office. He died within a month of his inauguration, replaced by his Vice President, John Tyler. Although Tyler had run on the Whig platform with Harrison, he was widely known as a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. Like Van Buren, Tyler was wildly unpopular as President and only served one term. He was replaced by James K. Polk, a protégé of Andrew Jackson. The fellow Tennessean was so like his famous predecessor, he was called “Young Hickory”. He too, served one term, dying shortly after leaving office. The Whig party successfully got war hero Zachary Taylor elected, but he only served just over a year, dying of a mysterious illness linked to food poisoning shortly after refusing to comply with Congress’s Fugitive Slave Act bill. He was succeeded by his weak Vice President, Millard Fillmore, who acquiesced to whatever demands the opposing party placed upon his desk. He only finished Taylor’s term. From that point, two more Democratic Presidents served: Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. Interestingly, since Andrew Jackson’s election, no President until Lincoln had been elected to two terms.

In addition to the Democratic stronghold at the Executive Mansion, the party had a strong voice in Congress. In addition to the Northern Democrats, the South added to their population by counting every slave as 3/5 of a person – multiplying their numbers for the House of Representatives. No wonder Lincoln’s election was an upset.

Lincoln understood that he threatened decades of power, wealth, and influence; he knew they would not easily yield it to a prairie lawyer upon whom they looked with aspersions – and who threatened a centuries-old institution that secured not only their wealth, but their power in Washington.

March 4, 1861 fell on a Monday, a pleasant day to start, but the weather later turned cloudy and chilly. Thousands of visitors thronged to see the outgoing and incoming Presidents, who rode together in a carriage to the portico of the unfinished Capitol building.

Buchanan and Lincoln hardly spoke. At one point, Buchanan purportedly mentioned to Lincoln, “If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel in returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.” The nation was in a dangerous place, and the 69-year-old Buchanan also keenly felt it.3

When Lincoln rose amid the wind and cold to give his inaugural address, he was met with little applause. His speech was indeed a peace offering, but he refused to give in to the threats of war and further secession. He did, however, promise not to further interfere with slavery, but only to keep true to the Constitution. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen,” he said, “and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” He reminded those who listened that he was sworn to protect the Constitution of the United States. He ended with a plea: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passions may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” 4

Lincoln then took the oath of office, administered by the aged and sickly Chief Justice Roger Taney.

Untold thousands who did not hear the address waited impatiently for it to appear in print. From New York to Richmond and beyond, crowds thronged the streets for the newspapers as soon as they were available. Many in the South did not sense any conciliation.

The better angels, unfortunately, did not manifest; the war Lincoln had hoped to avert still came.

In the midst of the terrible Civil War, Lincoln won reelection. His second inaugural speech, given on Saturday, March 4, 1865, is considered one of his greatest orations – perhaps only eclipsed by the President’s Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln was not well in the last days of winter that year. He had little sleep each night. He was anxious for the news of the war in its final weeks, and hate mail – along with vindictive attacks from newspapers – poured in. There were also threats against his life. “I know I’m in danger,” he told William H. Seward, “but I am not going to worry about it.” The war, he knew, was coming to an end, he just did not know when that end would come. His second inaugural speech, however, mirrored that hope in a new beginning at the end of the conflict.5

March 4 dawned dark and gloomy, with rain drizzling. Crowds thronged near the Capitol, where Lincoln arrived in his carriage. The streets were “a muddy paste” as women in their crinolines and men in their top hats assembled near the portico.6

Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Unionist, was the new Vice President Elect. Terrified of speaking before such a large assemblage, he had written to Lincoln, asking if he could take the oath of office in Nashville. Lincoln sent him a cable, insisting that he be in Washington.

Johnson was there, and downed at least two glasses of whiskey before his speech, which took place before the President’s. His speech was not memorable, and correspondent Noah Brooks remembered watching the faces of members of the Cabinet and Senators grimacing or writhing in their seats as he spoke. 7

Lincoln, who still felt unwell, listened patiently to the speech that preceded him. Then he rose, and as he approached the platform, the dark, blustery day was interrupted by a burst of sunshine, then “a tremendous shout, prolonged and loud, arose from the surging ocean of humanity.” It was the complete opposite of the welcome he had received four years earlier.8

Lincoln noticed Frederick Douglass in the crowd, and he instantly felt cheered. His speech was, like his first inaugural, carefully written and delivered with exactness.9

The President spoke of the late war, its enormous cost, and the importance of preserving the Union. “Fondly do we hope,” he continued, “fervently do we pray – that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.” He then ended with one of the most enduring passages ever uttered by a President: “With malice toward none, with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and for his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and among all nations.”10

Noah Brooks wrote that, as Lincoln uttered the final paragraph, “one could see moist eyes and even tearful cheeks ” among the crowd. He noted that the speech was “received in the most profound silence.”11

Lincoln then took the oath of office administered by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase.

“Among the memories of a lifetime,” penned Noah Brooks, “doubtless there are none more fondly cherished by those who were so fortunate as to stand near Lincoln at that historic moment.”12

There was at least one in attendance, however, who did not feel the same. His name was John Wilkes Booth. He had, earlier that day, tried to gain access to Lincoln in the Capitol, but had been prevented by police.

“Illuminated by the deceptive brilliance of a March sunburst ,” recalled Noah Brooks about that historic inaugural day, “ Lincoln was already standing in the shadow of death.”13

Lincoln had promised healing to all Americans, North and South, Union and Confederate – a magnanimous and truly merciful plan. It showed him for the humble and kindly human being that he was. The war had taken a heavy toll on him, physically and emotionally, and he was ready for the horror to end.

He could not have known that there was more horror to come.

Six weeks to the day after giving his second inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln was dead, assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. The unfortunate Andrew Johnson, as ill-prepared to serve as Chief Executive as he was in giving speeches, was a poor replacement.

The 16th President’s immortal addresses remain. They provide a glimpse into the mind and heart of a man who stood resolutely for his nation and his principles during excessively difficult times. His words still inspire.

Gettysburg, PA

The Gettysburg Experience, P.O. Box 4271 Gettysburg PA 17325 Phone 717.359.0776

© 2008 - 2024 Princess Publications, Inc.

Home

| Maps

| Directions

| Event Calendar

| Contact

| Advertisers

| Advertise with Us