Why We Celebrate Presidents Day

Why We Celebrate Presidents Day

by Diana Loski

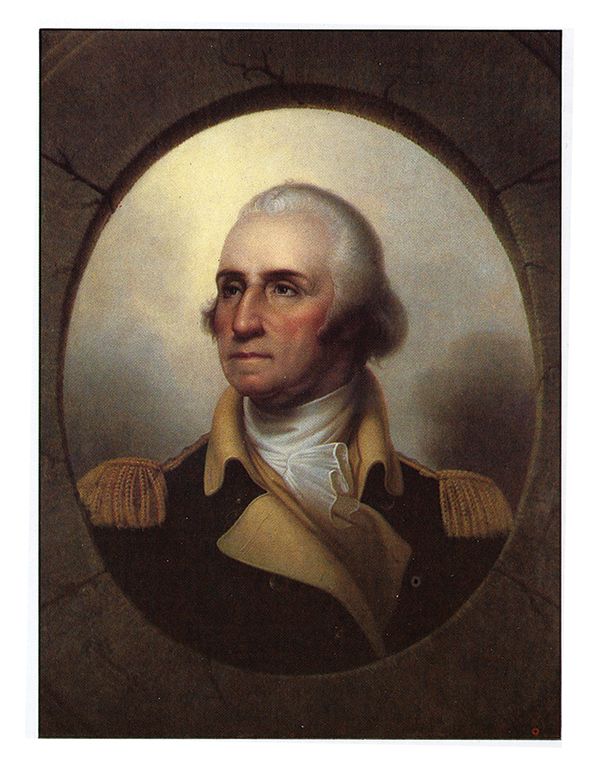

George Washington (1732-1799)

(Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

There are a few three-day weekends where certain Mondays constitute a federal holiday. One of these is the third Monday in February, designated as Presidents Day. The original meaning of the holiday is not as well-known as it once was. The precursor was first passed by Congress in 1879, and was created to honor the birthday of our nation’s first President, George Washington. 1

Washington was beloved by the masses for many years, both during his lifetime and for many decades after his death. He could have been a king, but refused. He could have been President for life, but again, he preferred a life of retirement after leading an army for years for independence, and then serving for two terms as the first President of the United States.

He became the template for the subsequent Presidents to follow – to acquire world power for a few years, then leave it behind.

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 (February 11 by the old calendar) in Westmoreland County, Virginia, near the banks of the Potomac River. He was the first son of his father’s second marriage. His parents were Augustus and Mary Ball Washington. By the age of six, Augustus and his family moved to the banks of the Rappahannock River to the town of Fredericksburg – the future site of a famous Civil War battle.

Young George lost his father when he was just eleven years old, and he was left in the care of his widowed mother. She was, by most accounts, a bit overbearing and she continually overspent their income. Washington was close to his older half-brother, Lawrence; when Lawrence died in 1752, he had named George as his secondary heir – the heiress was Lawrence’s daughter, Sarah, who died two years after her father. 2

With the unlikely and sudden acquisition of a substantial property, accompanied by his ambition to aid his mother’s overspending habits, George Washington needed to secure an income, first as a surveyor, then as a military commander. He was a colonel of British troops that answered to King George III of England. Later, when the colonies declared independence, Washington was the Commander of the Continental army of the American Revolution. His prowess helped America succeed in its independence, and in 1789 he was elected as the first President of the United States.

With his inherited estate, and by marrying the wealthy widow Martha Custis, Washington found himself a slave owner.

Washington was the type of man who understood the need for freedom, and he had not wanted to own slaves in the first place. The Virginia laws had complex and continually changing restrictions on freeing slaves, and Washington obeyed those laws. Washington refused, however, to buy or sell any human being, which he rightly saw as human trafficking. He encouraged his slaves to marry and promised he would never separate them. He also promised to free them upon his death. There were those who understandably insisted upon their freedom much sooner. When Washington lived in New York City during his first term as President, he took some of his slaves with him, and gave many their freedom there – as the laws were much simpler and lenient for emancipation. Mary Simpson was one of the cooks at Mount Vernon who accompanied the Washingtons to New York. She told the man she called “the General” that her dream was to be the proprietor of her own store. Washington granted her freedom, and gave her financial backing to start her new life. 3

Mary’s store was located at the corner of Cliff and John Streets, near the financial district in southern Manhattan. She was grateful to George Washington for helping her set up her grocery business. In addition to foodstuffs, Mary provided a bakery in her store: baking cookies, pies, and cakes for her customers. Every February 22, she baked a cake in honor of George Washington’s birthday, even after he had passed away in 1799. She gave her patrons a slice of cake – which she claimed she had prepared at Mount Vernon for the General – and offered punch and coffee to accompany the special dessert. As long as she lived, the birthday celebration took place in her Manhattan store. 4

Mary Simpson’s tradition soon spread to all of New York City. As the years passed, the populace remembered Washington’s birthday with parades, church services and other celebrations taking place each February 22. Eventually other cities joined in the commemoration.

In January 1879, Congress passed a statute making February 22 a federal holiday. By 1885, the entire country recognized Washington’s birthday. Throughout the nation, and especially in New York City, Washington’s birthday was commemorated with parades, speeches, and a special church service in Saint Paul’s Church – where Washington worshipped while serving his first term as President. These commemorative celebrations lasted well into the 20th century. 5

Another President, who by that time was as revered as the memory of Washington, was also born in February. On a snowy Sunday – February 12, 1809 – Abraham Lincoln entered the world less than a decade after Washington left it. Lauded by many historians as the nation’s greatest President for his role in keeping the nation together during the Civil War, Lincoln’s birthday was often celebrated and acknowledged, but it was never made a federal holiday. 6

In 1971, wishing to consolidate the two birthdays to a three-day weekend for federal employees, Congress passed another law, changing the date of the first President’s birthday commemoration to the third Monday in February. The holiday was renamed Presidents Day, with the intention of honoring Abraham Lincoln as well.

Over a half-century later, it seems that the original reasons for celebrating have been fading. Not all Presidents’ birthdays are supposed to be honored by the day – just Washington and Lincoln. Of the 46 Presidents on record, there are two others who were born in February: William Henry Harrison, born on February 9, 1773, and Ronald Reagan, born February 6, 1911. It seems that the months of October and November (with six Presidential births each), and May (at five Presidential births) have seen more Presidents enter the world than the month of February.

Nearly three hundred years after George Washington’s birth, we continue with the honors of commemorating his day. We should also remember Mary Simpson, the one to whom the honor of starting the holiday rightly belongs.

Washington was beloved by the masses for many years, both during his lifetime and for many decades after his death. He could have been a king, but refused. He could have been President for life, but again, he preferred a life of retirement after leading an army for years for independence, and then serving for two terms as the first President of the United States.

He became the template for the subsequent Presidents to follow – to acquire world power for a few years, then leave it behind.

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 (February 11 by the old calendar) in Westmoreland County, Virginia, near the banks of the Potomac River. He was the first son of his father’s second marriage. His parents were Augustus and Mary Ball Washington. By the age of six, Augustus and his family moved to the banks of the Rappahannock River to the town of Fredericksburg – the future site of a famous Civil War battle.

Young George lost his father when he was just eleven years old, and he was left in the care of his widowed mother. She was, by most accounts, a bit overbearing and she continually overspent their income. Washington was close to his older half-brother, Lawrence; when Lawrence died in 1752, he had named George as his secondary heir – the heiress was Lawrence’s daughter, Sarah, who died two years after her father. 2

With the unlikely and sudden acquisition of a substantial property, accompanied by his ambition to aid his mother’s overspending habits, George Washington needed to secure an income, first as a surveyor, then as a military commander. He was a colonel of British troops that answered to King George III of England. Later, when the colonies declared independence, Washington was the Commander of the Continental army of the American Revolution. His prowess helped America succeed in its independence, and in 1789 he was elected as the first President of the United States.

With his inherited estate, and by marrying the wealthy widow Martha Custis, Washington found himself a slave owner.

Washington was the type of man who understood the need for freedom, and he had not wanted to own slaves in the first place. The Virginia laws had complex and continually changing restrictions on freeing slaves, and Washington obeyed those laws. Washington refused, however, to buy or sell any human being, which he rightly saw as human trafficking. He encouraged his slaves to marry and promised he would never separate them. He also promised to free them upon his death. There were those who understandably insisted upon their freedom much sooner. When Washington lived in New York City during his first term as President, he took some of his slaves with him, and gave many their freedom there – as the laws were much simpler and lenient for emancipation. Mary Simpson was one of the cooks at Mount Vernon who accompanied the Washingtons to New York. She told the man she called “the General” that her dream was to be the proprietor of her own store. Washington granted her freedom, and gave her financial backing to start her new life. 3

Mary’s store was located at the corner of Cliff and John Streets, near the financial district in southern Manhattan. She was grateful to George Washington for helping her set up her grocery business. In addition to foodstuffs, Mary provided a bakery in her store: baking cookies, pies, and cakes for her customers. Every February 22, she baked a cake in honor of George Washington’s birthday, even after he had passed away in 1799. She gave her patrons a slice of cake – which she claimed she had prepared at Mount Vernon for the General – and offered punch and coffee to accompany the special dessert. As long as she lived, the birthday celebration took place in her Manhattan store. 4

Mary Simpson’s tradition soon spread to all of New York City. As the years passed, the populace remembered Washington’s birthday with parades, church services and other celebrations taking place each February 22. Eventually other cities joined in the commemoration.

In January 1879, Congress passed a statute making February 22 a federal holiday. By 1885, the entire country recognized Washington’s birthday. Throughout the nation, and especially in New York City, Washington’s birthday was commemorated with parades, speeches, and a special church service in Saint Paul’s Church – where Washington worshipped while serving his first term as President. These commemorative celebrations lasted well into the 20th century. 5

Another President, who by that time was as revered as the memory of Washington, was also born in February. On a snowy Sunday – February 12, 1809 – Abraham Lincoln entered the world less than a decade after Washington left it. Lauded by many historians as the nation’s greatest President for his role in keeping the nation together during the Civil War, Lincoln’s birthday was often celebrated and acknowledged, but it was never made a federal holiday. 6

In 1971, wishing to consolidate the two birthdays to a three-day weekend for federal employees, Congress passed another law, changing the date of the first President’s birthday commemoration to the third Monday in February. The holiday was renamed Presidents Day, with the intention of honoring Abraham Lincoln as well.

Over a half-century later, it seems that the original reasons for celebrating have been fading. Not all Presidents’ birthdays are supposed to be honored by the day – just Washington and Lincoln. Of the 46 Presidents on record, there are two others who were born in February: William Henry Harrison, born on February 9, 1773, and Ronald Reagan, born February 6, 1911. It seems that the months of October and November (with six Presidential births each), and May (at five Presidential births) have seen more Presidents enter the world than the month of February.

Nearly three hundred years after George Washington’s birth, we continue with the honors of commemorating his day. We should also remember Mary Simpson, the one to whom the honor of starting the holiday rightly belongs.

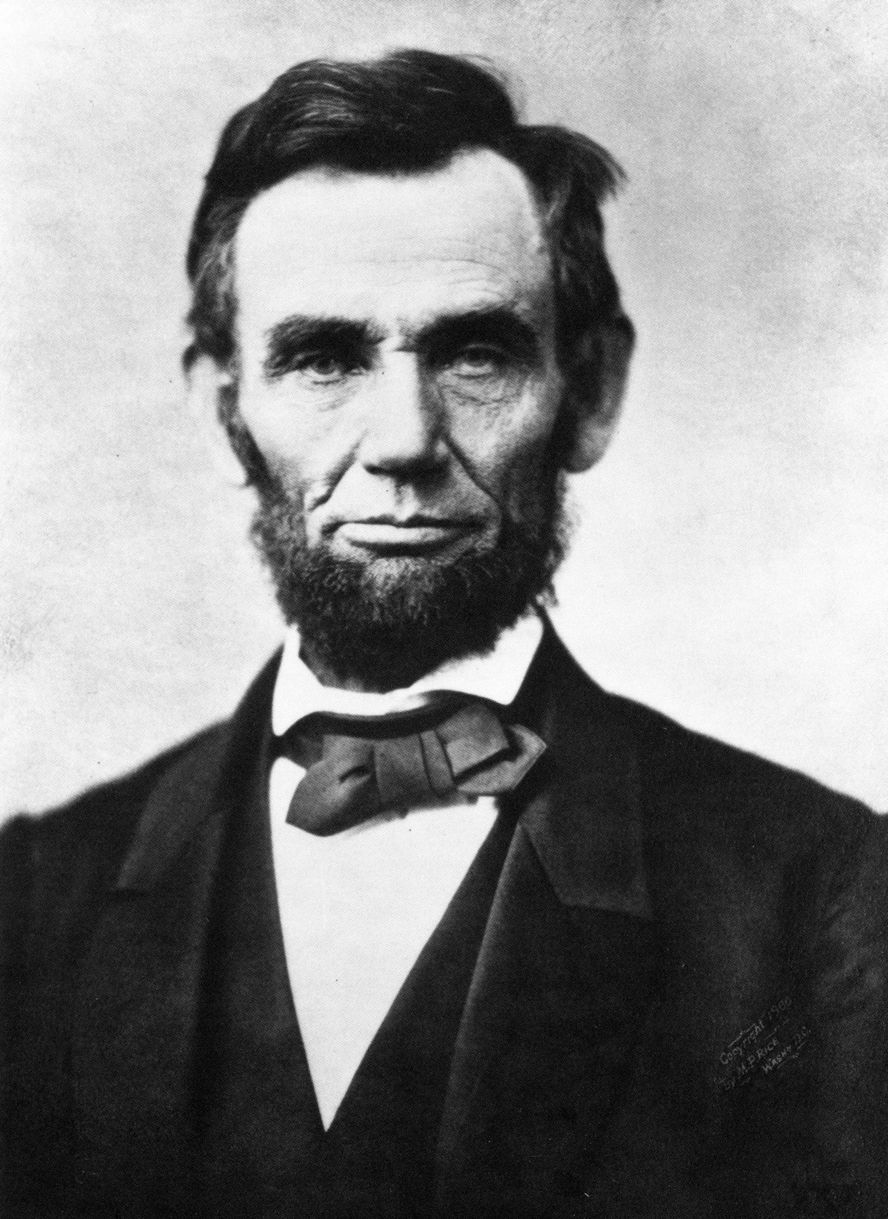

Lincoln's birth in February 1809 was another reason for

creating Presidents Day in 1971 (Library of Congress)

Sources: Alleman, Tillie Pierce. At Gettysburg: Or What A Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle. New York: W. Lake Borland, 1889 (Reprint: Gettysburg: Shriver House Museum, 2015). Brainard, S. Our War Songs. New York: S. Brainard’s Sons, 1887. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster 2005. Hillyer, Captain George. My Gettysburg Battle Experiences. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2005. Osbeck, Kenneth W. 101 Hymn Stories. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1982.

End Notes:

1. Brainarad, p. 37.

2. Osbeck, p. 35.

3. Brainard, p. 45.

4. Ibid., p. 59.

5. Alleman, p. 29.

6. Hillyer, pp. 25-26.

7. Ibid.

8.Goodwin, p. 727.

Gettysburg, PA

The Gettysburg Experience, P.O. Box 4271 Gettysburg PA 17325 Phone 717.359.0776

© 2008 - 2024 Princess Publications, Inc.

Home

| Maps

| Directions

| Event Calendar

| Contact

| Advertisers

| Advertise with Us