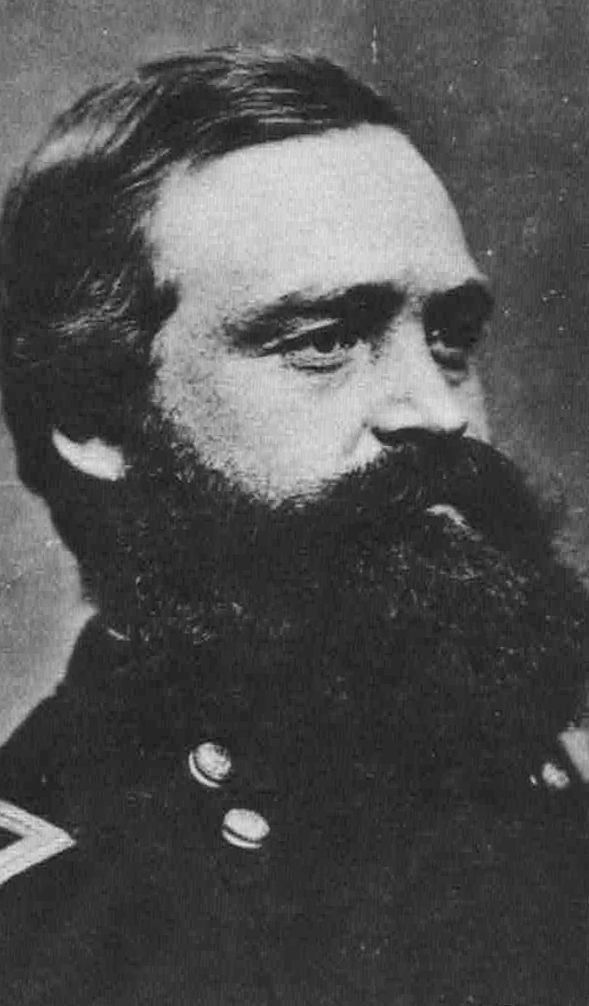

John Caldwell (National Archives)

Gettysburg’s second day was the deadliest of the three-day battle. Both Union and Confederate troops suffered extensive losses on that late Thursday afternoon and evening. One division commander, courageous and devoted to his duty, saw tremendous casualties among his men. He was a casualty too, albeit of the political kind. His name was John Caldwell.

John Curtis Caldwell was born in Lowell, Vermont on April 17, 1833, to George and Elizabeth Curtis Caldwell. The family moved to nearby Massachusetts, where John attended Amherst College. He graduated in 1855 and served as the principal of a private academy in Maine in the years before the war – seemingly uninterested in a military career. He married Martha Foster in 1857. Six children were born to the couple, but three died as infants – in 1859, 1860, and 1861 respectively. It was a difficult time for Mrs. Caldwell with only one surviving son at the time when her husband immediately enlisted his services to the Union in the summer of 1861.1

John Caldwell was mustered in as the colonel of the 11th Maine in the fall of 1861. He showed promising leadership and temerity in battle, as witnessed by his superiors. He was promoted to brigade command after the Battle of Seven Pines, part of the Peninsula Campaign, when the severe wounding of General Oliver O. Howard left a vacancy among officers. Caldwell capably led the First Brigade of the First Division, in Darius Couch’s Second Corps, Army of the Potomac. Caldwell was considered “one of the most experienced brigade commanders in the army.” 2

Caldwell was engaged at the Battle of Fredericksburg, where he was twice wounded during his brigade’s assault on Marye’s Heights.3

In the spring of 1863, the Union thrashing at Chancellorsville caused rifts in the Army of the Potomac. General Couch resigned in disgust at General Hooker’s inept handling of the battle. General Winfield S. Hancock replaced Couch. His promotion left an opening for division command, and John Caldwell received that promotion. When the army advanced to trek northward in pursuit of Lee’s army, Brigadier General John Caldwell was now in command of four small brigades: his former brigade of New England troops led by Colonel Edward Cross, Colonel Patrick Kelly of the Irish Brigade, Brigadier General Samuel Zook, and Colonel John Brooke.4

Neither General George Meade, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, nor General Robert E. Lee had planned to fight at Gettysburg. During the beginning of the engagement on July 1, 1863, neither general of their respective armies was present for the fighting. Both found themselves at about the same distance from the field of battle, with Lee in Cashtown and Meade in Taneytown, Maryland. General Meade sent Hancock, his most trusted corps commander, to Gettysburg to ascertain conditions there. Hancock asked John Gibbon, instead of John Caldwell, to command his Second Corps in his absence. Caldwell, as the ranking division commander, would normally have been placed in temporary corps command, but he was not chosen. Not knowing Caldwell as well as he knew and trusted John Gibbon, Hancock, with Meade’s approval, placed Gibbon in charge of the corps for the interim. It appears that General Caldwell did not complain.5

Caldwell and his division arrived at Gettysburg early on July 2. They deployed to the left of John Gibbon’s division on Cemetery Ridge, in the center of the Union defensive line.

In the afternoon of July 2, the Third Corps, which were deployed to the left of Caldwell’s men, suddenly advanced to the Emmitsburg Road. The troops remaining on the ridge were perplexed by the move. Across the Emmitsburg Road, General Longstreet saw an opportunity and immediately attacked.

The commander of the Union Third Corps, Dan Sickles, had not appreciated his troops’ position on the Union defensive line, and moved his men, without permission, to the Emmitsburg Road – a terrible military faux pas that would have left a less politically connected man facing serious charges. Many thousands would fall because of Sickles’s decision, and John Caldwell’s Division would be among those paying a heavy price for one commander’s disobedience.

The Confederate attack was deadly accurate and forceful, and soon Sickles’s men were falling and retreating. General David Birney, a division commander in the Third Corps, met with General Hancock near the Abraham Trostle house. “General Birney,” Hancock said as he greeted the beleaguered general, “you are nearly surrounded by the enemy.” Birney acknowledged his dangerous position and asked for reinforcements. Hancock told Caldwell to get ready – and Caldwell quickly complied. Hancock then said to Birney, “I have brought you these reinforcements. You will place them at your discretion.” He added somberly, “and I will hold you responsible for their lives.” 6

Caldwell and his men marched into the horrific storm of battle at the Wheatfield. Caldwell’s arrival made it possible for Birney to extricate his men – but why Birney did so was perplexing and did not seem wise. The reinforcements were meant to reinforce, not replace. Now Caldwell’s men were the ones surrounded by the determined phalanx in gray.

One of the soldiers from Caldwell’s Division remembered, “we marched forward…rapidly…the tumult was deafening…so that no words of command could be heard, and little could be seen but long lines of flame, and smoke and struggling masses of men.” 7

Another recalled, “how dark it was, so thick with battle-smoke. We would see the flash of every gun fired as if it were night.” 8

The situation was rife with chaos as troops were retreating and others arrived. “Generals, colonels, aides and orderlies galloped about through the smoke ,” another survivor remembered. “The hoarse and indistinguishable order of commanding officers, the screaming and bursting of shells, canister and shrapnel with their swishing sound as they tore through the struggling masses of humanity, the death screams of the animals, the groans of their human companions, wounded and dying and trampled underfoot by hurrying batteries, riderless horses and moving lines of battle, all combined in an indescribable roar of discordant elements – in fact, a perfect hell on earth.” 9

One of the generals described riding hurriedly among the masses was John Caldwell. As he saw the perilous situation, he was determined to find help. Locating Colonel Sweitzer’s brigade nearby, he asked for their support, and received permission from their corps commander, General Barnes – who was soon wounded. Caldwell then rode quickly back through the deathly Wheatfield, miraculously escaping being shot, where he encountered General Romeyn Ayres. Ayres’s division was also approaching, and Caldwell requested reinforcements from them as Caldwell’s men were falling like frost before the rising sun. Colonel Cross and General Zook were mortally wounded, and Brooke was shot in the ankle and unable to move. His men managed, with difficulty as Brooke was a large man, to get their commander off the field. Only Colonel Kelly remained unwounded, although his courageous Irishmen suffered heavy losses. With the position untenable, Caldwell’s men were forced to retreat, with staggering casualties.10

The Wheatfield was likely Gettysburg’s bloodiest field – even worse, acre for acre, than Pickett’s Charge. Both Union and Confederate dead were entangled among the broken, crimson stalks of wheat. “I have never seen so much damage done by the parties in so short a space of time,” wrote one Confederate from Kershaw’s Brigade.11

Caldwell and his division, having sustained major casualties, still had work to do at Gettysburg.

On July 3, General Lee, unable to turn the Union flanks, decided to attack the center line on Cemetery Ridge. The survivors of Hancock’s Second Corps held the middle, and they were resolute in repulsing the assault known to history as Pickett’s Charge.

The charge began in the afternoon after an approximate two-hour artillery bombardment from both sides of the Emmitsburg Road. The charge itself lasted less than an hour, but the hour was a desperate one. As the air grew thick and dark with missiles, bullets, and aerial dismembered body parts, the Union stronghold on Cemetery Ridge nearly gave way. General Hancock was shot and severely wounded; shortly afterward, General Gibbon was also wounded. John Caldwell then commanded the corps in those pivotal minutes. And the Union line held. Instead of a brevet for his gallantry, Caldwell received censure.

Because Dan Sickles refused to acknowledge any fault for his flagrant disregard for military obedience, blame for the terrible cost at Gettysburg flew toward other commanders. Few were exempt, including General Meade. Amazingly, General Birney, whom Hancock warned would be held responsible for the men of Caldwell’s Division, escaped censure. John Caldwell, instead, was blamed, albeit unfairly, by General Ayres, a fellow division commander in the Federal Fifth Corps, for the terrible fight in the Wheatfield. Caldwell was exonerated from any charges leveled against him, but he was jaded from the experience. In March 1864, when the army reduced its corps numbers from five to three – due mostly to the extreme losses at Gettysburg – John Caldwell was reassigned the Office of the War Department. In the midst of enduring the harsh criticism, there was a bright spot for the general. His daughter, Harriet, was born.12

At war’s end, General Caldwell offered a final military service. With the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, an honor guard was posted for the many funerals and on the train to Lincoln’s final resting place in Springfield. John Caldwell, by virtue of his office as President of the Advisory Board in Washington, was one of the commanders of that honor guard.13

John Caldwell remained in diplomatic service in the years after the war. He served as a state senator in Maine, where he and his family settled, and where another son, Charles, was born. Caldwell served as the ambassador to Chile, with headquarters in Valparaiso, and later to Paraguay and Uruguay, living in Montevideo, during the Grant administration. He then moved to Kansas with his wife, as his two sons and daughter were grown, and served there as President of the Board of Pardons.14

Mrs. Caldwell, in 1911, left for a short vacation to visit the couple’s daughter, Harriet, who was living with her husband in Calais, Maine. While there, Mrs. Caldwell died. Bereft and in ill health with the onset of dementia, General Caldwell retired in 1912 from his position in Kansas and moved to Maine, in the care of his daughter. He died there on August 30, 1912. The cause of death was listed as “senile decay”. It appears he was the last surviving member of the honor guard that followed the 16th President’s body to its burial in Springfield.15

Across the river from the town of Calais, Maine is St. Stephen’s Rural Cemetery, in Canada. It is the final resting place for both John and Martha Caldwell. The spot was chosen by their daughter, Harriet Caldwell Murchie, due to its proximity to the town.16

The passage of years has led to rising fame for some Civil War veterans, and obscurity for others. John Caldwell is one of the latter. With determination to see his nation protected, he succeeded in aiding the Union cause – including suffering physical and emotional wounds for the sake of the nation. He showed his greatest courage in the maelstrom that was Gettysburg. He deserves to be remembered.

John Curtis Caldwell was born in Lowell, Vermont on April 17, 1833, to George and Elizabeth Curtis Caldwell. The family moved to nearby Massachusetts, where John attended Amherst College. He graduated in 1855 and served as the principal of a private academy in Maine in the years before the war – seemingly uninterested in a military career. He married Martha Foster in 1857. Six children were born to the couple, but three died as infants – in 1859, 1860, and 1861 respectively. It was a difficult time for Mrs. Caldwell with only one surviving son at the time when her husband immediately enlisted his services to the Union in the summer of 1861.1

John Caldwell was mustered in as the colonel of the 11th Maine in the fall of 1861. He showed promising leadership and temerity in battle, as witnessed by his superiors. He was promoted to brigade command after the Battle of Seven Pines, part of the Peninsula Campaign, when the severe wounding of General Oliver O. Howard left a vacancy among officers. Caldwell capably led the First Brigade of the First Division, in Darius Couch’s Second Corps, Army of the Potomac. Caldwell was considered “one of the most experienced brigade commanders in the army.” 2

Caldwell was engaged at the Battle of Fredericksburg, where he was twice wounded during his brigade’s assault on Marye’s Heights.3

In the spring of 1863, the Union thrashing at Chancellorsville caused rifts in the Army of the Potomac. General Couch resigned in disgust at General Hooker’s inept handling of the battle. General Winfield S. Hancock replaced Couch. His promotion left an opening for division command, and John Caldwell received that promotion. When the army advanced to trek northward in pursuit of Lee’s army, Brigadier General John Caldwell was now in command of four small brigades: his former brigade of New England troops led by Colonel Edward Cross, Colonel Patrick Kelly of the Irish Brigade, Brigadier General Samuel Zook, and Colonel John Brooke.4

Neither General George Meade, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, nor General Robert E. Lee had planned to fight at Gettysburg. During the beginning of the engagement on July 1, 1863, neither general of their respective armies was present for the fighting. Both found themselves at about the same distance from the field of battle, with Lee in Cashtown and Meade in Taneytown, Maryland. General Meade sent Hancock, his most trusted corps commander, to Gettysburg to ascertain conditions there. Hancock asked John Gibbon, instead of John Caldwell, to command his Second Corps in his absence. Caldwell, as the ranking division commander, would normally have been placed in temporary corps command, but he was not chosen. Not knowing Caldwell as well as he knew and trusted John Gibbon, Hancock, with Meade’s approval, placed Gibbon in charge of the corps for the interim. It appears that General Caldwell did not complain.5

Caldwell and his division arrived at Gettysburg early on July 2. They deployed to the left of John Gibbon’s division on Cemetery Ridge, in the center of the Union defensive line.

In the afternoon of July 2, the Third Corps, which were deployed to the left of Caldwell’s men, suddenly advanced to the Emmitsburg Road. The troops remaining on the ridge were perplexed by the move. Across the Emmitsburg Road, General Longstreet saw an opportunity and immediately attacked.

The commander of the Union Third Corps, Dan Sickles, had not appreciated his troops’ position on the Union defensive line, and moved his men, without permission, to the Emmitsburg Road – a terrible military faux pas that would have left a less politically connected man facing serious charges. Many thousands would fall because of Sickles’s decision, and John Caldwell’s Division would be among those paying a heavy price for one commander’s disobedience.

The Confederate attack was deadly accurate and forceful, and soon Sickles’s men were falling and retreating. General David Birney, a division commander in the Third Corps, met with General Hancock near the Abraham Trostle house. “General Birney,” Hancock said as he greeted the beleaguered general, “you are nearly surrounded by the enemy.” Birney acknowledged his dangerous position and asked for reinforcements. Hancock told Caldwell to get ready – and Caldwell quickly complied. Hancock then said to Birney, “I have brought you these reinforcements. You will place them at your discretion.” He added somberly, “and I will hold you responsible for their lives.” 6

Caldwell and his men marched into the horrific storm of battle at the Wheatfield. Caldwell’s arrival made it possible for Birney to extricate his men – but why Birney did so was perplexing and did not seem wise. The reinforcements were meant to reinforce, not replace. Now Caldwell’s men were the ones surrounded by the determined phalanx in gray.

One of the soldiers from Caldwell’s Division remembered, “we marched forward…rapidly…the tumult was deafening…so that no words of command could be heard, and little could be seen but long lines of flame, and smoke and struggling masses of men.” 7

Another recalled, “how dark it was, so thick with battle-smoke. We would see the flash of every gun fired as if it were night.” 8

The situation was rife with chaos as troops were retreating and others arrived. “Generals, colonels, aides and orderlies galloped about through the smoke ,” another survivor remembered. “The hoarse and indistinguishable order of commanding officers, the screaming and bursting of shells, canister and shrapnel with their swishing sound as they tore through the struggling masses of humanity, the death screams of the animals, the groans of their human companions, wounded and dying and trampled underfoot by hurrying batteries, riderless horses and moving lines of battle, all combined in an indescribable roar of discordant elements – in fact, a perfect hell on earth.” 9

One of the generals described riding hurriedly among the masses was John Caldwell. As he saw the perilous situation, he was determined to find help. Locating Colonel Sweitzer’s brigade nearby, he asked for their support, and received permission from their corps commander, General Barnes – who was soon wounded. Caldwell then rode quickly back through the deathly Wheatfield, miraculously escaping being shot, where he encountered General Romeyn Ayres. Ayres’s division was also approaching, and Caldwell requested reinforcements from them as Caldwell’s men were falling like frost before the rising sun. Colonel Cross and General Zook were mortally wounded, and Brooke was shot in the ankle and unable to move. His men managed, with difficulty as Brooke was a large man, to get their commander off the field. Only Colonel Kelly remained unwounded, although his courageous Irishmen suffered heavy losses. With the position untenable, Caldwell’s men were forced to retreat, with staggering casualties.10

The Wheatfield was likely Gettysburg’s bloodiest field – even worse, acre for acre, than Pickett’s Charge. Both Union and Confederate dead were entangled among the broken, crimson stalks of wheat. “I have never seen so much damage done by the parties in so short a space of time,” wrote one Confederate from Kershaw’s Brigade.11

Caldwell and his division, having sustained major casualties, still had work to do at Gettysburg.

On July 3, General Lee, unable to turn the Union flanks, decided to attack the center line on Cemetery Ridge. The survivors of Hancock’s Second Corps held the middle, and they were resolute in repulsing the assault known to history as Pickett’s Charge.

The charge began in the afternoon after an approximate two-hour artillery bombardment from both sides of the Emmitsburg Road. The charge itself lasted less than an hour, but the hour was a desperate one. As the air grew thick and dark with missiles, bullets, and aerial dismembered body parts, the Union stronghold on Cemetery Ridge nearly gave way. General Hancock was shot and severely wounded; shortly afterward, General Gibbon was also wounded. John Caldwell then commanded the corps in those pivotal minutes. And the Union line held. Instead of a brevet for his gallantry, Caldwell received censure.

Because Dan Sickles refused to acknowledge any fault for his flagrant disregard for military obedience, blame for the terrible cost at Gettysburg flew toward other commanders. Few were exempt, including General Meade. Amazingly, General Birney, whom Hancock warned would be held responsible for the men of Caldwell’s Division, escaped censure. John Caldwell, instead, was blamed, albeit unfairly, by General Ayres, a fellow division commander in the Federal Fifth Corps, for the terrible fight in the Wheatfield. Caldwell was exonerated from any charges leveled against him, but he was jaded from the experience. In March 1864, when the army reduced its corps numbers from five to three – due mostly to the extreme losses at Gettysburg – John Caldwell was reassigned the Office of the War Department. In the midst of enduring the harsh criticism, there was a bright spot for the general. His daughter, Harriet, was born.12

At war’s end, General Caldwell offered a final military service. With the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, an honor guard was posted for the many funerals and on the train to Lincoln’s final resting place in Springfield. John Caldwell, by virtue of his office as President of the Advisory Board in Washington, was one of the commanders of that honor guard.13

John Caldwell remained in diplomatic service in the years after the war. He served as a state senator in Maine, where he and his family settled, and where another son, Charles, was born. Caldwell served as the ambassador to Chile, with headquarters in Valparaiso, and later to Paraguay and Uruguay, living in Montevideo, during the Grant administration. He then moved to Kansas with his wife, as his two sons and daughter were grown, and served there as President of the Board of Pardons.14

Mrs. Caldwell, in 1911, left for a short vacation to visit the couple’s daughter, Harriet, who was living with her husband in Calais, Maine. While there, Mrs. Caldwell died. Bereft and in ill health with the onset of dementia, General Caldwell retired in 1912 from his position in Kansas and moved to Maine, in the care of his daughter. He died there on August 30, 1912. The cause of death was listed as “senile decay”. It appears he was the last surviving member of the honor guard that followed the 16th President’s body to its burial in Springfield.15

Across the river from the town of Calais, Maine is St. Stephen’s Rural Cemetery, in Canada. It is the final resting place for both John and Martha Caldwell. The spot was chosen by their daughter, Harriet Caldwell Murchie, due to its proximity to the town.16

The passage of years has led to rising fame for some Civil War veterans, and obscurity for others. John Caldwell is one of the latter. With determination to see his nation protected, he succeeded in aiding the Union cause – including suffering physical and emotional wounds for the sake of the nation. He showed his greatest courage in the maelstrom that was Gettysburg. He deserves to be remembered.

End Notes:

1. Drake, p. 32. John Caldwell Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Augusta Morning Sentinel, 04 Sep., 1912.

2. Tucker, p. 109. Pfanz, p. 72.

3. Gallagher, ed. p. 482.

4. Warner, p. 64. Pfanz, p. 445.

5. Pfanz, p. 472. Warner, pp. 64, 171.

6. Tucker, p. 141.

7. Gambone, pp. 13-14.

8. Ibid., p. 12.

9. Ibid.

10. Pfanz, p. 287.

11. Wycoff, p. 44.

12. Gallagher, ed. p. 482. Caldwell Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Ayres was not distinguished at Gettysburg, and Caldwell’s Division certainly fought bravely and well.

13. Augusta Morning Sentinel, 04 Sep., 1912.

14. Ibid.

15. John C. and Martha Caldwell Death Records, Ancestry.com. Augusta Morning Sentinel, 04 Sep., 1912. 16. Augusta Morning Sentinel, 04 Sep., 1912.

16. Augusta Morning Sentinel, 04 Sep., 1912.