Sources: 6 th New York Cavalry File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). The Buffalo Evening News, Dec. 29, 1883. “Eccentricities from our Archives: The Man Who Collected Lincoln” Fords.org. Elmira Daily Advertiser, Dec. 31, 1883. The Elmira Sunday Morning Tidings, Dec. 30, 1883. Good, Timothy S. We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts . Jackson, MS: The University Press of Mississippi, 1995. Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies . New York: Random House, 2004. Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr. Twenty Days . New York: Castle Books, 1965. The Rochester Democrat, Dec. 27, 1883. All historic newspapers found at nyshistoricnewspapers.org.

- Home

- Maps

- Directions

- Event Calendar

- Contact

- Advertisers

- Advertise with Us

-

Archive

- Jeff Harding

-

2025 Archive

- The Leister Farm: The Cottage Headquarters

- The Devil's Den Photographer

- July 1865: A New Beginning

- Editor's Corner - A Look Back

- J.J. Pettigrew: The Last Fallen Star

- Elsie Singmaster: Gettysburg's Distinguished Daughter

- They Were At Gettysburg

- Editor's Corner: An Ounce of Prevention

- John Newton: The Eminent Engineer

- Decade by Decade: 100 Years of History

- Eddie Plank: A Gettysburg Celebritry

- September 1864: A Turning Point

- Editor's Corner: Kangaroo Words

- In Libby Prison: One Soldier's Experience

- Judson Kilpatrick: "Nothing but Fame"

- Eisenhower Trivia

- The Postmaster's Wife

- Editor's Corner: Contonyms

- An Autumn Surprise

- General Charles Collis: "So Positive a Character"

- America's Great Communicator

- Christmas in Pennsylvania

- George Shriver's Last Christmas

- Basil Biggs: A Son of Goodwill

- A Bucktail to the Rescue

- A Quest Fufilled

- 2024 Archive

- 2023 Archive

- 2022 Archive

- 2021 Archive

- 2020 Archive

A Christmas Murder

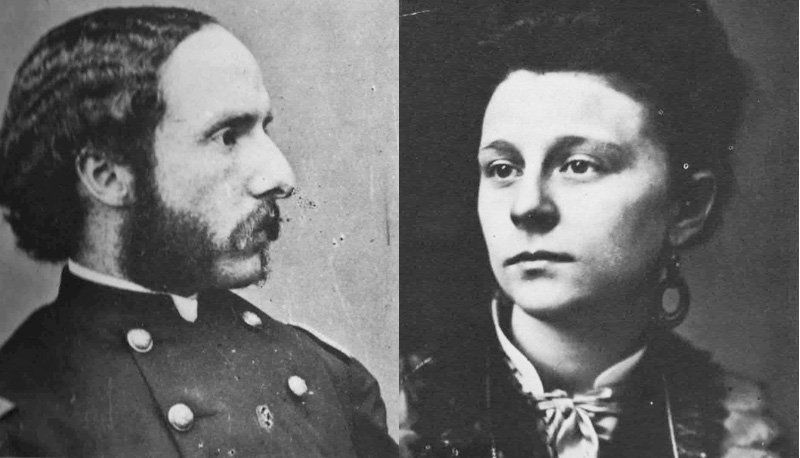

Major Henry Rathbone (left) and Clara Harris

(Library of Congress)

On Christmas Eve, 1883, the Hannoverscher Courier

in Hanover, Germany printed a grisly story. The previous night, Colonel Henry Rathbone, the current U.S. ambassador to that country, had murdered his wife, Clara. He then attempted to commit suicide.1

It was a Christmas murder of historic proportions – and one of the most plaintive chronicles to result from the aftermath of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln – an event that had occurred eighteen years earlier.

On April 14, 1865, the war was coming to an end after the surrender of General Lee’s army at Appomattox. It was Good Friday – a day that many spent in church. Lincoln, however, went to the theater to celebrate. He did not wish to go, but felt that the people were expecting him. The Fords had published in the newspaper that the President and General Grant would attend the benefit performance of Our American Cousin

that evening. When the Grants turned down the invitation, the Lincolns asked several other people to join them that night, including Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and Thomas T. Eckert, the chief of the Military Telegraph Office in the War Department. Mrs. Grant strongly disliked Mary Lincoln and refused to attend. Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War, admonished Lincoln that he, too, should not attend the theater that night. Lincoln then asked for Eckert – a man of considerable strength and military acumen – a man with whom Lincoln felt protected. Stanton refused to allow Eckert to go; he said the man could not be spared. Eventually, the lovely Clara Harris, daughter of Republican senator Ira Harris, and her fiancé, Major Henry Rathbone, accepted the invitation.2

Ira Harris was a staunch Union supporter and a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln, though Mary Lincoln did not care for him. He had insisted that the Lincolns’ eldest son, Robert, serve in the Union army; and Mary did not want her son in danger in the field. She liked his daughter, however. Clara was considered “a cultured, brilliant woman” by those who knew her; she had accompanied the Lincolns to the theater during previous engagements.3

Major Henry Rathbone was not only Clara’s fiancé, he was her step-brother. Born in 1837 in Albany, New York to Jared Lewis Rathbone and the former Pauline Penney, he was also considered bright and highly cultured. His father was the mayor of Albany until his untimely death. In all, four children were born to the Rathbones, but only two sons survived childhood: Henry and his younger brother Jared. After his father died, his mother married the widowed Ira Harris in 1848. Henry, at age 11, moved into his stepfather’s home and was welcomed by three stepsiblings: William, Clara, and Louise.4

Henry and Clara formed a special bond throughout their adolescent years, which was interrupted by war in 1861. Henry enlisted in the U.S. Regulars, serving in the 12th Infantry with the rank of captain. Ira Harris, his stepfather, was an ardent Union supporter, raising a regiment of cavalry, the 6th New York Cavalry, also known as the Ira Harris Guards. The unit fought at Gettysburg, as part of Colonel Devin’s Brigade, Buford’s Division. Ira Harris, elected as a senator in Washington, did not lead them in the field.5

Rathbone was brevetted for gallantry during the Petersburg Campaign in the summer of 1864, where he received the rank of major. Through Senator Harris’s influence, in early 1865 Rathbone was appointed by the President as the Assistant Adjutant General of Volunteers.6

Rathbone and Miss Harris, then, were well known to the Lincolns. While they had been farther down on the list, they eagerly accepted the invitation, and the Lincoln carriage collected them at the Harris residence en route to the theater.

The disastrous events that transpired at Ford’s Theater never left Henry Rathbone. It is unclear if he had been told to protect the President, and even if that were the case, he must have felt that Lincoln was safe in their private box on the balcony. He positioned himself farthest away from the President, sitting on a sofa, while Lincoln rested in a rocking chair on the other side, with the two women between them.

When John Wilkes Booth crept into the box and shot the President at about 10:30 p.m., during the Third Act, Rathbone, like the rest of the audience, had been engrossed in the play. Upon hearing the shot, he quickly turned and saw the assassin enveloped in smoke from the recent firing of his single-shot derringer. Rathbone grabbed Booth, but the murderer was armed with a Bowie knife, and lifted it to stab the young major. Rathbone saw the knife raised to strike him, and parried the blow with his arm – which Booth viciously sliced. Bleeding profusely, for Booth’s knife had nicked an artery, Rathbone again grabbed Booth as he climbed over the box to escape. Booth resisted and dropped to the stage below – and made his escape.7

Rathbone called out for someone to stop the assailant, then called for a doctor. He attempted to open the door of the box and found it snugly locked: Booth had wedged a board across the entrance. With his injured arm, he opened it with difficulty. He continued to bleed, attempting to help with the mortally wounded Lincoln. He eventually fainted from the loss of blood and was taken to the Harris home, where he spent many weeks convalescing. His beloved fiancée, Clara, faithfully nursed him. The couple wed two years later, on July 11, 1867.

The marriage seemed happy. Three children were born to the couple. Only Clara and Rathbone’s closest friends knew that he suffered bouts of depression from the awful night at Ford’s Theater. James Barrett, a Union veteran and Rathbone’s personal friend and attorney said, “I don’t think that he ever recovered from the shock of fright in President Lincoln’s box at the theater. The scene always haunted his mind.”8

He also never recovered from the guilt. And it was overwhelming guilt.

Both General Grant and Lincoln’s bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon were quoted in newspapers after the assassination as averring that if they had been there they would have saved Lincoln. Rathbone undoubtedly read these accounts. He had been the one there, and he had not been able to save the Commander-in-Chief. Through his recurring bouts of “despondency and moodiness

” Clara was there to help him9

Then, in 1881, President James A. Garfield was assassinated, and Rathbone’s depression increased. The new President, Chester A. Arthur, was a family friend. He sent the Rathbones to Germany. Henry, who was cultured and well-liked, hoped that the trip overseas would help him to heal from his nightmares of the night when Lincoln was murdered. Unfortunately, the attacks of melancholia only grew worse.

As the holidays approached, Henry’s dark moods increased. Suffering also from dyspepsia, a severe ulcer likely caused by his anxiety, he grew increasingly suspicious and jealous of his wife, “though there was no cause whatever for any such feelings on his part.”10

On the night of December 23, 1883, Rathbone acted as though he thought an assailant was in the house, attempting to abduct his children. Clara wisely told her sister, Louise, who was living with them and tending the children, to lock the door to the children's room. Henry then grew more agitated, following Clara into their bedroom. There, he promptly shot his wife three times in the chest. One bullet went through her body and “came out at the backbone.” He then stabbed her repeatedly, with one thrust penetrating her heart. He then stabbed himself.11

Louise was the first person at the scene. After alerting the police, she sent a telegram home. Ira Harris had died in 1875, but Mrs. Harris still lived and was devastated by the news. Clara's brother William Harris immediately booked passage on a ship to retrieve Louise and the children. He became the guardian of the three orphans. 12

The newspapers at the time believed that Henry Rathbone would not survive his injuries. He did, however. Still rambling and delusionary, he was decreed insane. He was committed to an asylum in Germany, where he remained until his death in 1911.13

Amazingly, the three children managed to continue their lives without permanent damage. Henry Riggs Rathbone, the namesake son of the Civil War major, followed in his grandfather’s and step-grandfather’s footsteps, becoming a statesman. He was a Congressman for the state of New York for many years. He was instrumental in the U.S government’s purchase of the substantial Lincoln memorabilia collected by Union veteran Osborn Oldroyd. The collection is currently housed at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C.14

During the holiday season of 1883, a murder in Germany sent shock waves around the world. A marriage was doomed because an innocent young couple accepted an invitation to the theater. What so many believed was the beginning of peace on earth ended in horror that night in 1865. A beloved President had indeed saved the Union, but Henry Rathbone had not been able to save his President, and the nightmare he endured because of it ended tragically eighteen years later.

End Notes:

1. Kauffman, p. 474.

2. Kunhardt, p. 26. Lincoln had a foreboding that Friday, as he had personally asked for Eckert, for his protection.

3. Elmira Daily Advertiser, Dec. 31, 1883. Robert Lincoln did eventually serve on General Grant’s staff during the war. Like Ira Harris, Robert also thought he should do his duty.

4. The Rochester Democrat, Dec. 27, 1883.

5. 6

th

New York Cavalry File, GNMP.

6. Kunhardt, p. 26.

7. Good, p. 16. Kunhardt, p. 39.

8. Elmira Sunday Morning Tidings, Dec. 30, 1883.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. The Buffalo Evening News, Dec. 29, 1883. The Elmira Daily Advertiser, Dec. 31, 1883.The Elmira Sunday Morning Tidings, Dec. 30, 1883.

12. The Buffalo Evening News, Dec. 29, 1883.

13. The Elmira Sunday Morning Tidings, Dec. 30, 1883. The Rochester Democrat, Dec. 27, 1883.

14. “Eccentricities”, Fords.org. The Oldroyd Collection was for a time housed as a museum at the Lincoln home in Springfield, Illinois, then at the Petersen House – the boarding house where Lincoln died. The government now owns the collection.

Gettysburg, PA

New Paragraph

The Gettysburg Experience, P.O. Box 4271 Gettysburg PA 17325 Phone 717.359.0776

© 2025 Princess Publications, Inc.

Home

| Maps

| Directions

| Event Calendar

| Contact

| Advertisers

| Advertise with Us