Gettysburg connections can be found all over the world. From Antarctica, where there is a Mount Reynolds (named for the brother of Gettysburg general John Reynolds), to the Himalayas (where a hut was named Wildwood in memory of a childhood home in Gettysburg), to the multitude of monuments to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, the parallel to Gettysburg is ubiquitous.

Arizona’s highest peak, at 12, 643 feet, bears the name of Mount Humphreys. It is located near Flagstaff, the central peak of three mountains which rise above northern Arizona – a fertile area that differs from the otherwise arid state. This part of the state is considered a part of the Colorado Plateau. The mountain range where Mount Humphreys is found is known as The San Francisco Peaks, located in the Cococino National Forest.1

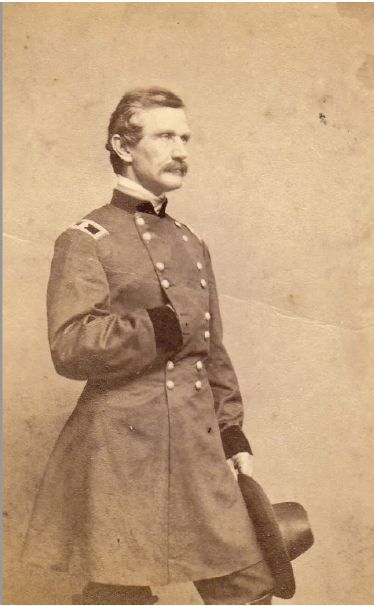

Mount Humphreys, a majestic sight that commands attention, is named for a Civil War general who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg in the summer of 1863.

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys was a native of Philadelphia, born in 1810, the son of a naval architect. Humphreys possessed an amazing aptitude for engineering and a love of all things military. He graduated from West Point in 1831 and was a model leader during the Civil War.2

He led a division at Gettysburg, and fought in the Peach Orchard with the Federal Third Corps. At the end of the battle, Humphreys replaced Daniel Butterfield as General George Meade’s Chief of Staff, as Butterfield had been wounded during the battle.

In 1864, General Humphreys replaced General Winfield Scott Hancock as commander of the Union Second Corps. The former Third Corps had ceased to exist after the Battle of Gettysburg, as the casualties had been so severe and widespread. Had General Humphreys not fought in the Peach Orchard, the casualties would have numbered even more, and exponentially so. By war’s end he received a brevet to Major General for gallantry on the field.

By war’s end, Humphreys had participated in over seventy engagements, from his days on the frontier after his graduation from West Point, to Appomattox Court House.3

He was considered by many contemporaries as “the great soldier of the Army of the Potomac.”4

After the war, Humphreys was named as the Chief of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He served in that post from 1866 to his retirement in 1879. There were few Civil War generals more renowned than Andrew A. Humphreys by that time.5

Humphreys Peak was named in honor of the engineer and general in 1870.6

General Humphreys lived with his wife on Connecticut Avenue in Washington D.C. He died two days after Christmas, while sitting in his chair in his parlor, of an apparent heart attack. He was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington.7

While the general has gone, along with the rest of the combatants from America’s worst war, the mountain named in his memory continues to stand tall – a site worth visiting, on grounds that are considered sacred in Native American lore. Across the nation, another site is considered sacred ground, too. Wherever great sacrifice has been made for the life, liberty, and well-being of generations to come, there is something inexplicable about that place. Gettysburg, like so many fields of conflict around the world, is one of them.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica. “Humphreys Peak”. www.britannica.com, 19 October, 2010. The Philadelphia Times, 29 December, 1883. Loski, Diana. “Andrew A. Humphreys: The Great Soldier of the Army of the Potomac.” The Gettysburg Experience, April 2023. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.

End Notes:

1. “Humphreys Peak”, britannica.com.

2. Loski, The Gettysburg Experience, Apr. 2023.

3. The Philadelphia Times, 29 Dec., 1883.

4. Ibid.

5. Warner, p. 241.

6. “Humphreys Peak”, britannica.com.

7. Loski, The GettysburgExperience, April 2023. The Philadelphia Times, 29 Dec., 1883. Warner, p. 241.