A Woman of Courage

by Diana Loski

Catherine Garlach

(Adams County Historical Society)

During the three-day conflict at Gettysburg, many residents of the town fled, but many others made the choice to remain behind, hidden in their cellars. The Garlach family, who resided on Baltimore Street, chose the latter. The matriarch of the house, Catherine, found herself thrust into action to save her young family. She also saved the life of at least one soldier.

Catherine Garlach was born Catherine Polly Little on February 24, 1822 in Adams County, a descendant of German immigrants who changed their appellation from Klein, which means Little

in English. Her paternal grandfather, Andrew Klein, came to Pennsylvania before the American Revolution and was a veteran of that war. He changed his appellation to its English equivalent and resided in what was then York (later Adams) County. He eventually settled in St. Thomas, Franklin County, where he died in 1845.1

Catherine’s parents, Richard and Margaret Little, lived in Gettysburg. As a young woman, she met German immigrant John Henry Garlach, when he was a boarder in the home of one of her relatives. The couple married in St. James Lutheran Church in Gettysburg in 1840, when Catherine was eighteen and Henry was twenty-three. Henry’s father, also named John Henry Garlach, lived with the couple until his death in 1851.2

Henry, Jr. was a gifted cabinet and furniture maker. He and Catherine lived in a home that also functioned as Henry’s carpentry business in Gettysburg, which is located at 319 to 323 Baltimore Street. Henry had purchased the home in 1855. In addition to creating furniture, Henry also made coffins, and later set up a mortuary with his son, John William.3

When war came to Gettysburg in the summer of 1863, Henry and Catherine had five living children: Anna, George, William, Catherine (Katie) and Francis (Frank) – the last just an infant during that fateful summer.4

Anna, the eldest of the Garlach children, was up early with her mother on July 1, 1863, when she heard the sound that would change their lives. “When I heard the first shot fired in the morning,” she remembered, “I was sitting in the yard stringing beans for dinner and was frightened. I finished the beans, however, and mother cooked them with a piece of ham.”5

Anna, the only chronicler of the Garlach family’s ordeal during the battle, never mentioned her father or her brother, George, in her writings. George, who was fourteen at the time, volunteered to serve as an ambulance driver for the many wounded. He was not at home during the battle. Henry Garlach, too, was absent. There are conflicting stories about his whereabouts. One is that he panicked and hid in the woods, according to Adjutant Roberts, a wounded soldier from the 17th Maine who convalesced in the Garlach home after the fight. The other story was that Henry, who heard the ominous sounds of gunfire that morning of July 1, went to Cemetery Hill to get a better view of the battle. When the Confederates took over the town, which included his home on Baltimore Street, he was unable to return. Regardless of the reason, Henry Garlach was not at home during the three-day conflict, and Catherine was left alone to protect her family.6

The Federal Eleventh Corps arrived at Gettysburg on July 1 and went into battle during the afternoon north of the town. Many in the ranks spoke only German, and as a result, many of their commanders out of necessity spoke that language. One of them was Brigadier General Alexander Schimmelfennig, a Prussian engineer who emigrated to Pennsylvania at the age of twenty. Settling in Philadelphia, he immediately offered his services to the Union when war erupted in the spring of 1861. He was part of the Eleventh Corps when it suffered the ignominious rout at Chancellorsville and was one of the commanders determined to erase the stain of cowardice that floated around the army about his troops.7

General Schimmelfennig and Catherine Garlach would soon be historically linked.

While the battle escalated north and west of town, the civilians were told to go to their basements. With Mr. Garlach absent, Catherine noticed that with the recent rains, many cellars on Baltimore Street were flooded, including theirs. The family went a few doors north to the Shriver House, which had been abandoned, and took refuge in their cellar for a few hours. As the Union and Confederates fought through town in the early evening of July 1, Catherine decided that she would prefer to stay at home to keep Confederates away from her property. She returned home with her children. With the aid of her son, Will, Catherine pulled firewood logs from an outbuilding and placed them on the flooded dirt floor. She and Will placed planks over the logs, making the cellar habitable. In all, eleven people hid in the Garlach cellar for the duration of the battle.8

During twilight, Catherine noticed that the firing had stopped. She took the scraps from dinner, filled the slop bucket and cautiously went to the backyard, where the family’s hogs were penned. As she began to feed them, she was startled by a voice that said, “Be quiet and do not say anything.”9

It was General Schimmelfennig, who had taken shelter between two large swill barrels and the family woodpile next to the shed and hog pen. He explained to Mrs. Garlach that on the Union retreat from outside of town, in an attempt to reach Cemetery Hill, his horse had been shot from under him. Forced to distance himself from the Confederates who were close behind, he had discovered “an old water course in [their] yard…covered with a wooden culvert.” He quickly crawled inside and waited until dark. Realizing that Confederates had gained full control of the street, he realized he could not escape. 0

Catherine readily agreed to help him.

The next day, making “a pretense of going to the swill barrel to empty a bucket,” Mrs. Garlach instead had some bread and water with her, and quietly slipped them to the hidden general. Later, fearing that she might have unwittingly alerted the Confederates, she decided that she would not make the attempt again. The water and bread were all that General Schimmelfennig had to eat or drink for the remaining two days.11

Before the conflict was over, Catherine still had a few battles to fight.

On the third day, “a soldier burst in the front door and started up the stairs.” Catherine, in the cellar with the rest, heard the noise and immediately ascended to the first floor. She arrived in time to see a soldier in gray going up the stairs to the second floor. Catherine grabbed his coat and said, “You can’t go up there. You will draw fire on this house full of defenseless women and children.” The soldier refused to oblige, but Catherine held firmly onto his coat and refused to let him go. Finally, the soldier relented and left. Not long afterward another would-be-sharpshooter came in and attempted to scale the stairs to the attic. Catherine caught him by the coat and again refused to let him go a step farther. He too left the house.12

On the same day she chased sharpshooters from the house, she heard yet more commotion upstairs. Two Confederate soldiers told her they needed access to her husband’s shop. Their commander, General Barksdale, had died and they wanted a coffin for his burial. Catherine told them there was plenty of wood in the back and to take all they wanted, but to stay out of the house. She refused to budge, again, until they vacated the premises.13

“Mrs. Garlach was a kind and shrewd lady,” remembered one contemporary. She had also proved that she was not defenseless in the face of danger. Her actions protected her family and those dependent upon her for safety during those days of peril.14

On the morning of July 4, before the onslaught of rain that hampered General Lee’s retreat, it was clear that the battle was at an end. The civilians came out of their homes and into the streets. Catherine was anxious to learn if General Schimmelfennig had been captured, and quickly stepped toward the back of the house. Her daughter, Anna, followed and remembered that “He was already out of his hiding place before she reached him. When I first saw him he was moving across our yard…He was walking stiff and cramped.” 5

The Garlach home, Gettysburg

(Author photo)

“That Schimmelfennig appreciated the kindness of Mrs. Garlach goes without saying,” wrote one who chronicled the incident.17

General Schimmelfennig had requested a transfer from the Eleventh Corps in 1864, but was stricken with malaria and was forced to convalesce for many months. In 1865 he fell fatally ill with tuberculosis. He died just months after the war ended, on September 5, 1865.18

After his death, the general’s relatives, who had heard of Mrs. Garlach’s help during the Battle of Gettysburg, came to visit the family. They explained that they had heard the story, as related to them by the late commander, and requested to see the shed, barrels, and woodpile where he had hidden to escape certain capture – and likely an even earlier death. Mrs. Garlach took them to his hiding place. They took pictures and soon left.19

Henry Garlach, who returned after the battle, continued in business with his son Will until his death in 1887. Widowed and aged, Catherine moved from the home, staying with family in town until her death in 1893. Both are buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

In 1905, the famous shed and hog pin were razed due to the ravages of time. It had become a true Gettysburg landmark.20

While naysayers at times accused General Schimmelfennig of cowardice, Anna Garlach Kitzmiller quickly came to his defense: “I could see nothing cowardly in what he did. The Union soldier had a horror of Southern prisons and would resort to anything to escape from capture. He did the only thing possible to save his life.”21

Without the aid of Catherine Garlach, the general and those to whom she invited to stay in refuge would have found themselves in a far more dangerous situation.

A truly courageous yet unassuming woman, the memory of Catherine Garlach is a worthy one. At Gettysburg, there were many others just like her, equally memorable in their devotion to those who needed them.

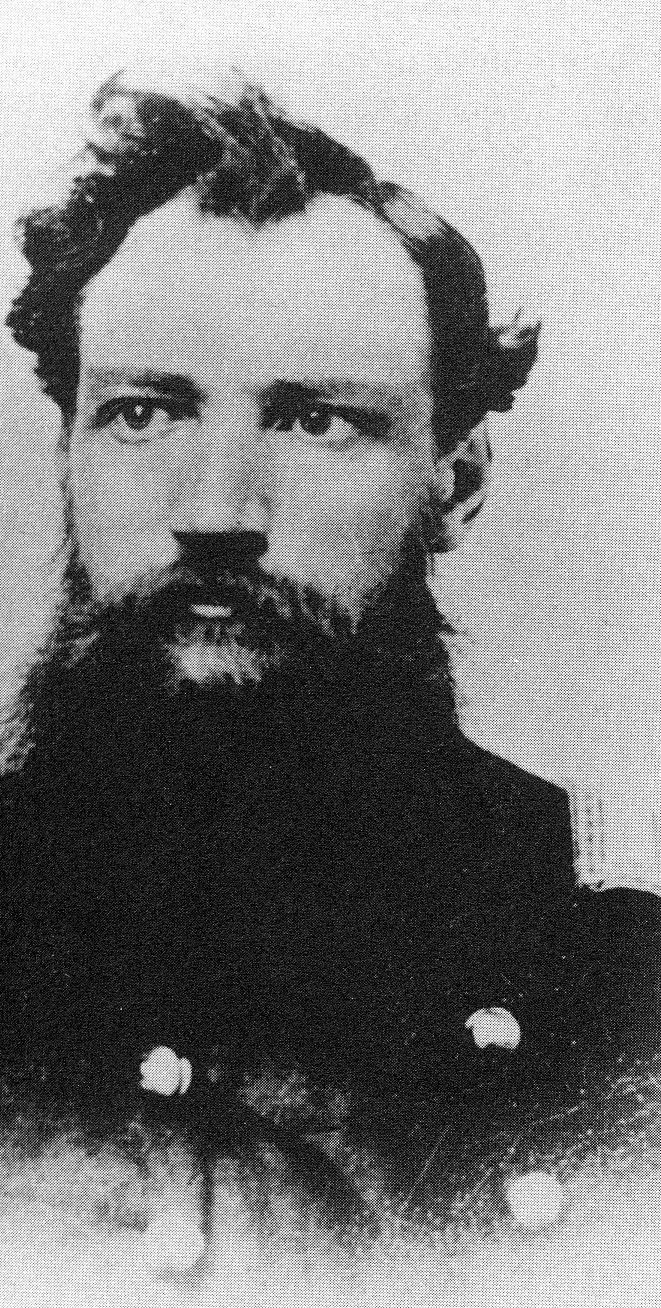

Alexander Schimmelfennig(

U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA)

Sources: 1850 Census, Adams County, PA; 1860 Census, Adams County, PA, Ancestry.com

. Catherine Little Garlach Family Record, Ancestry.com

. Garlach Family File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Garlach Anna (Kitzmiller), Civilian Accounts File, ACHS. Garlach, Henry and Catherine Little Marriage Record, Ancestry.com

. Thomas Little Military Pension Records, Pennsylvania State Archives, Vol. 12, copy, Ancestry.com. The Gettysburg Times, 26 March, 1917. The Gettysburg Star & Sentinel, 17 May, 1905. Schimmelfennig, Alexander, Participants Accounts File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders

. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1964 (reprint, 1996).

End Notes:

1. Catherine Little Garlach Family Records, Ancestry.com. Thomas Little Military Pension Records, PA State Archives, p. 456.

2. U.S. Census 1850. Garlach/Little Marriage Record, Ancestry.com.

3. U.S. 1860 Census. The Gettysburg Times, 26 March, 1917.

4. Garlach Family File, ACHS.

5. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

6. Schimmelfennig Participant Accounts File, GNMP.

7. Warner, p. 424. The appellation Schimmelfennig means “minter of coin” in German.

8. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

9. Ibid.

10. Star & Sentinel, 17 May, 1905. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

11. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Star & Sentinel, 17 May, 1905.

15. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

16. Ibid.

17. Star & Sentinel, 17 May, 1905.

18. Warner, p. 424.

19. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

20. Star & Sentinel, 17 May, 1905.

21. Anna Garlach Civilian Accounts File,

ACHS.