Before the Storm

by Diana Loski

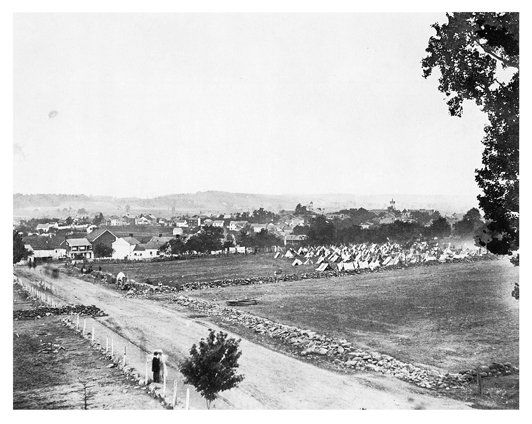

1863 Gettysburg

(Gettysburg National Military Park)

In June 1863 a big storm was brewing. All the signs were there for those who took the time to notice.

The Civil War was into its third year, and the populace, North and South, were war weary. The Union forces, though having lost greatly during the first two years, were becoming better outfitted and trained, especially with the cavalry and artillery. In the west, Ulysses S. Grant was pummeling the town of Vicksburg with a siege. The Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, a native of Mississippi, wanted his closest general and ally, Robert E. Lee, to take his army to Mississippi and stop Grant. General Lee, still amazed from his stunning victory at Chancellorsville, had just reorganized his army; he did not wish to march them through the swamps of the deep South for over a thousand miles. He had a plan.

If Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were to march northward and threaten Washington, D.C., either Lincoln would insist that Grant return east and stop Lee’s men – or the Confederates would take the Union capital, and the war could feasibly end – making Grant’s siege little more than an academic exercise. Additionally, war-torn Virginia would get a respite from the two years of fighting, and farmers could again plant crops and feed the populace. Lee’s soldiers could find what they needed in the North: food, medical and other needed supplies, shoes, hats, and other clothing, and horses. One Southern soldier exclaimed: “ O! What a relief it will be to our country to be rid of our army for some time! I hope we may keep away…and so relieve the calls for supplies that have been so long made upon our people.” In the waning days of May, Lee and his army set off for the North.1

At the time, General Joe Hooker, still the commander of the Army of the Potomac, kept a watchful eye on Washington. Lee then headed into the Blue Ridge Mountains, hoping to lose themselves from Union spies. Still flushed with their recent victory, the Confederates did not take into consideration that their Federal counterparts were becoming more skilled, and that perhaps invading the Union territory might inspire the men in blue to fight more valiantly.

On June 9, 1863, the Confederate cavalry met their Union counterparts at the Battle of Brandy Station. General Jeb Stuart had staged a review of his troops for civilians, and was surprised by General Alfred Pleasonton and his Union cavalry troops. The battle was fierce, with many charges, countercharges, giving up ground and taking it again. In the end over 1,400 men fell as casualties – a significant number for cavalry fights. While the Union retreated across the Rappahannock and Stuart claimed victory, he nevertheless had been caught unaware. He also noted that the Union forces fought much better than before.2

As the week passed, the Union cavalry forces tailed Lee’s infantry, and noticed that they were indeed heading toward Pennsylvania. They sent the information to both Hooker and Lincoln. Lincoln was already planning on a replacement for Hooker. It was a difficult decision to make, with the Union army on the move and another battle imminent.

While General Lee crossed the Potomac on Saturday, June 27, already a large contingent of his army had precipitated him. On Friday, June 26, the townspeople of Gettysburg were alarmed to hear the news of approaching Confederates. They were part of Jubal Early’s Division, Richard Ewell’s Second Corps. They weren’t there for battle – rather, they were shopping.

Lee issued his General Order #72, forbidding destruction to private property and inflicting damage on private citizens. Jubal Early was too far away to hear, and had he known, he would likely have ignored the order all the same.

Nineteen-year-old Nellie Aughinbaugh worked for a milliner downtown. As the owner rushed in with the news “ The Rebels are coming, I tell you !” the other workers immediately left the shop. Nellie, not concerned as former rumors had always come to nothing, kept working on a bonnet. Mr. Martin, the milliner, grabbed the hat from her hands and said, “Go home, girl! The Rebels are right at the edge of town!”3

Fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce remembered, “They wanted horses, clothing, anything and almost everything they could conveniently carry away….Nor were they particular about asking. Whatever suited them they took.”4

Sallie Myers, a local school teacher, wrote, “About four o’clock the long looked for Rebels made their appearance, and such a mean looking lot of men I never saw in my life…They were yelling like fiends.”5

Nellie Aughinbaugh agreed. As she ran from Mr. Martin’s store into the Diamond en route to her home on Carlisle Street, she saw the ragged troops arriving “with cheers and yells…and wheeling their horses around and around the square. I was frightened…and ran with all my might every step of the way home.”6

General Early, who had been ordered to march to York by way of Gettysburg, entered the town with little resistance. A group of militia – the 26th Pennsylvania – attempted to stop them. These men were new recruits and were vastly outnumbered. Early’s men swept them away and continued into town. He made demands of the civilian population for 10,000 pairs of shoes and 500 hats or $10,000 in cash – which the locals claimed they did not have. There was no shoe factory in Gettysburg, as the Confederates wrongly had believed. While Early remonstrated with the local leaders, his men ransacked homes, raided shops and took liquor from wherever they found it. The Confederates also stripped the Gettysburg people of their horses and mules, if they were fortunate enough to find them.7

Elizabeth Thorn, expectant with her fourth child and missing her husband who had enlisted to fight for the Union, was so frightened by the sight and noise of the invaders that she fainted. “They fired off their revolvers to scare people ,” she said. “They chased people out and…jumped over fences.” When they strode to Elizabeth’s house, which was the gatehouse of the Evergreen Cemetery, they asked for food – of which they were all clearly in need. Elizabeth and her aged mother quickly complied. “They said we should not be afraid of them,” Elizabeth remembered, “they were not going to hurt us like the yankeys [sic] did their ladies.”8

Not all civilians were frightened of the Confederates. A small but significant minority of Copperheads – Northern people who supported the Confederacy – lived in and around Gettysburg. A few helped the Southerners with information. In addition to these, there also those living in the county who were devout conscientious objectors, mostly Pennsylvania Dutch farmers and Mennonites. They refused to help either side and firmly wished to be left alone.

The Confederates had not come to stay. The following day they pulled out for York, burning two railroad bridges on their way. On Sunday, June 28, Early’s troops reached York, and the Union army wended its way closer to Pennsylvania.

At three a.m. on Sunday, June 28, George Meade was awakened in his tent by Colonel James Hardie of the War Office. Hardie said that he “had come to give him trouble”, and Meade thought he was under arrest. Hardie lit a candle and told him that Lincoln had chosen General Meade to be the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Meade objected; he wanted to refuse the post, but Hardie insisted that it was an order. Meade hastily rose to dress, and commented, “Well, I’ve been tried and condemned without a hearing, and I suppose I shall have to go to the execution.”9

General Meade was the seventh commander of the Army of the Potomac in the two years of the war. All of his former commanders had met with disaster to their careers. Meade expected the same treatment. He ordered the army northward with all possible speed.

Just hours later, Henry Harrison, a spy, approached General Longstreet’s headquarters near Chambersburg. The word of Meade’s rise to command had reached the newspapers, and Henry Harrison spread the news to Longstreet. Harrison also related that the entire Union army was on the march, heading toward Gettysburg. Lee was aghast that they had been surprised. “Where on earth is my cavalry?” he asked.10

Soldiers from both sides of the conflict remembered the march toward Gettysburg as one of the most grueling. “I never suffered more in my life than I did on this march,” one Union soldier recalled.11

On Tuesday, June 30, the citizens of Gettysburg were overjoyed to see men in blue riding into their town. They were John Buford’s Cavalry Division. As the horse soldiers rode northward on Washington Street, a group of Gettysburg girls rushed to greet them with water, food, flowers, and song. The men heartily thanked them. “They were Union soldiers and that was enough for me, for I then knew we had protection,” Tillie Pierce remembered.12

John Buford, the Kentucky- born general of these troops, wasted no time becoming familiar with the land and the information he gleaned about the Confederate troops nearby. One Gettysburg youth saw the general near his headquarters, the Eagle Hotel, on Chambersburg Street. “General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me,” he said, “entirely alone, facing to the west and in profound thought.”13

The Battle at Brandy Station, in the recent past, was only a precursor to what Buford knew was coming. The terrific storm of battle was going to occur, as all the elements were about to combine. Buford knew it, and he committed to it at that moment.

The general wrote dispatches to General Meade, the army commander, and John Reynolds, the wing commander immediately south with the closest Union infantry troops. He then told his men to warn the populace, and tell them to leave if they could. “Acting on the advice of soldiers, many people had packed some belongings and left town,” Sallie Myers wrote. “Others, like the Myers family, did not.”14

“As we lay down for the night,” Tillie Pierce remembered, “little did we think what the morrow would bring.”15

The following day, Wednesday, July 1, a dark and leaden storm unleashed its fury upon the town of Gettysburg – and its ramifications are still felt 158 years later.

The Civil War was into its third year, and the populace, North and South, were war weary. The Union forces, though having lost greatly during the first two years, were becoming better outfitted and trained, especially with the cavalry and artillery. In the west, Ulysses S. Grant was pummeling the town of Vicksburg with a siege. The Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, a native of Mississippi, wanted his closest general and ally, Robert E. Lee, to take his army to Mississippi and stop Grant. General Lee, still amazed from his stunning victory at Chancellorsville, had just reorganized his army; he did not wish to march them through the swamps of the deep South for over a thousand miles. He had a plan.

If Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were to march northward and threaten Washington, D.C., either Lincoln would insist that Grant return east and stop Lee’s men – or the Confederates would take the Union capital, and the war could feasibly end – making Grant’s siege little more than an academic exercise. Additionally, war-torn Virginia would get a respite from the two years of fighting, and farmers could again plant crops and feed the populace. Lee’s soldiers could find what they needed in the North: food, medical and other needed supplies, shoes, hats, and other clothing, and horses. One Southern soldier exclaimed: “ O! What a relief it will be to our country to be rid of our army for some time! I hope we may keep away…and so relieve the calls for supplies that have been so long made upon our people.” In the waning days of May, Lee and his army set off for the North.1

At the time, General Joe Hooker, still the commander of the Army of the Potomac, kept a watchful eye on Washington. Lee then headed into the Blue Ridge Mountains, hoping to lose themselves from Union spies. Still flushed with their recent victory, the Confederates did not take into consideration that their Federal counterparts were becoming more skilled, and that perhaps invading the Union territory might inspire the men in blue to fight more valiantly.

On June 9, 1863, the Confederate cavalry met their Union counterparts at the Battle of Brandy Station. General Jeb Stuart had staged a review of his troops for civilians, and was surprised by General Alfred Pleasonton and his Union cavalry troops. The battle was fierce, with many charges, countercharges, giving up ground and taking it again. In the end over 1,400 men fell as casualties – a significant number for cavalry fights. While the Union retreated across the Rappahannock and Stuart claimed victory, he nevertheless had been caught unaware. He also noted that the Union forces fought much better than before.2

As the week passed, the Union cavalry forces tailed Lee’s infantry, and noticed that they were indeed heading toward Pennsylvania. They sent the information to both Hooker and Lincoln. Lincoln was already planning on a replacement for Hooker. It was a difficult decision to make, with the Union army on the move and another battle imminent.

While General Lee crossed the Potomac on Saturday, June 27, already a large contingent of his army had precipitated him. On Friday, June 26, the townspeople of Gettysburg were alarmed to hear the news of approaching Confederates. They were part of Jubal Early’s Division, Richard Ewell’s Second Corps. They weren’t there for battle – rather, they were shopping.

Lee issued his General Order #72, forbidding destruction to private property and inflicting damage on private citizens. Jubal Early was too far away to hear, and had he known, he would likely have ignored the order all the same.

Nineteen-year-old Nellie Aughinbaugh worked for a milliner downtown. As the owner rushed in with the news “ The Rebels are coming, I tell you !” the other workers immediately left the shop. Nellie, not concerned as former rumors had always come to nothing, kept working on a bonnet. Mr. Martin, the milliner, grabbed the hat from her hands and said, “Go home, girl! The Rebels are right at the edge of town!”3

Fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce remembered, “They wanted horses, clothing, anything and almost everything they could conveniently carry away….Nor were they particular about asking. Whatever suited them they took.”4

Sallie Myers, a local school teacher, wrote, “About four o’clock the long looked for Rebels made their appearance, and such a mean looking lot of men I never saw in my life…They were yelling like fiends.”5

Nellie Aughinbaugh agreed. As she ran from Mr. Martin’s store into the Diamond en route to her home on Carlisle Street, she saw the ragged troops arriving “with cheers and yells…and wheeling their horses around and around the square. I was frightened…and ran with all my might every step of the way home.”6

General Early, who had been ordered to march to York by way of Gettysburg, entered the town with little resistance. A group of militia – the 26th Pennsylvania – attempted to stop them. These men were new recruits and were vastly outnumbered. Early’s men swept them away and continued into town. He made demands of the civilian population for 10,000 pairs of shoes and 500 hats or $10,000 in cash – which the locals claimed they did not have. There was no shoe factory in Gettysburg, as the Confederates wrongly had believed. While Early remonstrated with the local leaders, his men ransacked homes, raided shops and took liquor from wherever they found it. The Confederates also stripped the Gettysburg people of their horses and mules, if they were fortunate enough to find them.7

Elizabeth Thorn, expectant with her fourth child and missing her husband who had enlisted to fight for the Union, was so frightened by the sight and noise of the invaders that she fainted. “They fired off their revolvers to scare people ,” she said. “They chased people out and…jumped over fences.” When they strode to Elizabeth’s house, which was the gatehouse of the Evergreen Cemetery, they asked for food – of which they were all clearly in need. Elizabeth and her aged mother quickly complied. “They said we should not be afraid of them,” Elizabeth remembered, “they were not going to hurt us like the yankeys [sic] did their ladies.”8

Not all civilians were frightened of the Confederates. A small but significant minority of Copperheads – Northern people who supported the Confederacy – lived in and around Gettysburg. A few helped the Southerners with information. In addition to these, there also those living in the county who were devout conscientious objectors, mostly Pennsylvania Dutch farmers and Mennonites. They refused to help either side and firmly wished to be left alone.

The Confederates had not come to stay. The following day they pulled out for York, burning two railroad bridges on their way. On Sunday, June 28, Early’s troops reached York, and the Union army wended its way closer to Pennsylvania.

At three a.m. on Sunday, June 28, George Meade was awakened in his tent by Colonel James Hardie of the War Office. Hardie said that he “had come to give him trouble”, and Meade thought he was under arrest. Hardie lit a candle and told him that Lincoln had chosen General Meade to be the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Meade objected; he wanted to refuse the post, but Hardie insisted that it was an order. Meade hastily rose to dress, and commented, “Well, I’ve been tried and condemned without a hearing, and I suppose I shall have to go to the execution.”9

General Meade was the seventh commander of the Army of the Potomac in the two years of the war. All of his former commanders had met with disaster to their careers. Meade expected the same treatment. He ordered the army northward with all possible speed.

Just hours later, Henry Harrison, a spy, approached General Longstreet’s headquarters near Chambersburg. The word of Meade’s rise to command had reached the newspapers, and Henry Harrison spread the news to Longstreet. Harrison also related that the entire Union army was on the march, heading toward Gettysburg. Lee was aghast that they had been surprised. “Where on earth is my cavalry?” he asked.10

Soldiers from both sides of the conflict remembered the march toward Gettysburg as one of the most grueling. “I never suffered more in my life than I did on this march,” one Union soldier recalled.11

On Tuesday, June 30, the citizens of Gettysburg were overjoyed to see men in blue riding into their town. They were John Buford’s Cavalry Division. As the horse soldiers rode northward on Washington Street, a group of Gettysburg girls rushed to greet them with water, food, flowers, and song. The men heartily thanked them. “They were Union soldiers and that was enough for me, for I then knew we had protection,” Tillie Pierce remembered.12

John Buford, the Kentucky- born general of these troops, wasted no time becoming familiar with the land and the information he gleaned about the Confederate troops nearby. One Gettysburg youth saw the general near his headquarters, the Eagle Hotel, on Chambersburg Street. “General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me,” he said, “entirely alone, facing to the west and in profound thought.”13

The Battle at Brandy Station, in the recent past, was only a precursor to what Buford knew was coming. The terrific storm of battle was going to occur, as all the elements were about to combine. Buford knew it, and he committed to it at that moment.

The general wrote dispatches to General Meade, the army commander, and John Reynolds, the wing commander immediately south with the closest Union infantry troops. He then told his men to warn the populace, and tell them to leave if they could. “Acting on the advice of soldiers, many people had packed some belongings and left town,” Sallie Myers wrote. “Others, like the Myers family, did not.”14

“As we lay down for the night,” Tillie Pierce remembered, “little did we think what the morrow would bring.”15

The following day, Wednesday, July 1, a dark and leaden storm unleashed its fury upon the town of Gettysburg – and its ramifications are still felt 158 years later.

John Buford (seated) & staff

(Library of Congress)

End Notes:

1. Coddington, p. 159.

2. Foote, pp. 437-438.

3. Aughinbaugh Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

4. Alleman, p. 22.

5. Rogers, p. 146.

6. Aughinbaugh Civilian Accounts File, ACHS. The Diamond is Lincoln Square.

7. Coddington, p. 167.

8. Thorn, p. 3.

9. Cleaves, p. 124.

10. Longstreet, p. 347. Foote, p. 456.

11. Rhodes, p. 113.

12. Alleman, p. 29.

13. Daniel Skelly Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.

14. Rogers, p. 148.

15. Alleman, p. 30.

![<p><strong> </strong>In June 1863 a big storm was brewing. All the signs were there for those who took the time to notice. <br /> <br /> The Civil War was into its third year, and the populace, North and South, were war weary. The Union forces, though having lost greatly during the first two years, were becoming better outfitted and trained, especially with the cavalry and artillery. In the west, Ulysses S. Grant was pummeling the town of Vicksburg with a siege. The Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, a native of Mississippi, wanted his closest general and ally, Robert E. Lee, to take his army to Mississippi and stop Grant. General Lee, still amazed from his stunning victory at Chancellorsville, had just reorganized his army; he did not wish to march them through the swamps of the deep South for over a thousand miles. He had a plan.<br> If Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were to march northward and threaten Washington, D.C., either Lincoln would insist that Grant return east and stop Lee’s men – or the Confederates would take the Union capital, and the war could feasibly end – making Grant’s siege little more than an academic exercise. Additionally, war-torn Virginia would get a respite from the two years of fighting, and farmers could again plant crops and feed the populace. Lee’s soldiers could find what they needed in the North: food, medical and other needed supplies, shoes, hats, and other clothing, and horses. One Southern soldier exclaimed: “<em>O! What a relief it will be to our country to be rid of our army for some time! I hope we may keep away…and so relieve the calls for supplies that have been so long made upon our people</em>.” In the waning days of May, Lee and his army set off for the North.<sup>1</sup> <br /> <br /> At the time, General Joe Hooker, still the commander of the Army of the Potomac, kept a watchful eye on Washington. Lee then headed into the Blue Ridge Mountains, hoping to lose themselves from Union spies. Still flushed with their recent victory, the Confederates did not take into consideration that their Federal counterparts were becoming more skilled, and that perhaps invading the Union territory might inspire the men in blue to fight more valiantly.<br> On June 9, 1863, the Confederate cavalry met their Union counterparts at the Battle of Brandy Station. General Jeb Stuart had staged a review of his troops for civilians, and was surprised by General Alfred Pleasonton and his Union cavalry troops. The battle was fierce, with many charges, countercharges, giving up ground and taking it again. In the end over 1,400 men fell as casualties – a significant number for cavalry fights. While the Union retreated across the Rappahannock and Stuart claimed victory, he nevertheless had been caught unaware. He also noted that the Union forces fought much better than before.<sup>2</sup> <br /> <br /> As the week passed, the Union cavalry forces tailed Lee’s infantry, and noticed that they were indeed heading toward Pennsylvania. They sent the information to both Hooker and Lincoln. Lincoln was already planning on a replacement for Hooker. It was a difficult decision to make, with the Union army on the move and another battle imminent.<br> While General Lee crossed the Potomac on Saturday, June 27, already a large contingent of his army had precipitated him. On Friday, June 26, the townspeople of Gettysburg were alarmed to hear the news of approaching Confederates. They were part of Jubal Early’s Division, Richard Ewell’s Second Corps. They weren’t there for battle – rather, they were shopping.<br> Lee issued his General Order #72, forbidding destruction to private property and inflicting damage on private citizens. Jubal Early was too far away to hear, and had he known, he would likely have ignored the order all the same.<br> Nineteen-year-old Nellie Aughinbaugh worked for a milliner downtown. As the owner rushed in with the news “<em>The Rebels are coming, I tell you</em>!” the other workers immediately left the shop. Nellie, not concerned as former rumors had always come to nothing, kept working on a bonnet. Mr. Martin, the milliner, grabbed the hat from her hands and said, “<em>Go home, girl! The Rebels are right at the edge of town</em>!”<sup>3</sup> <br /> <br /> Fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce remembered, “<em>They wanted horses, clothing, anything and almost everything they could conveniently carry away….Nor were they particular about asking. Whatever suited them they took.</em>”<sup>4</sup> <br /> <br /> Sallie Myers, a local school teacher, wrote, “<em>About four o’clock the long looked for Rebels made their appearance, and such a mean looking lot of men I never saw in my life…They were yelling like fiends</em>.”<sup>5</sup> <br /> <br /> Nellie Aughinbaugh agreed. As she ran from Mr. Martin’s store into the Diamond en route to her home on Carlisle Street, she saw the ragged troops arriving “<em>with cheers and yells…and wheeling their horses around and around the square. I was frightened…and ran with all my might every step of the way home.</em>”<sup>6</sup> <br /> <br /> General Early, who had been ordered to march to York by way of Gettysburg, entered the town with little resistance. A group of militia – the 26th Pennsylvania – attempted to stop them. These men were new recruits and were vastly outnumbered. Early’s men swept them away and continued into town. He made demands of the civilian population for 10,000 pairs of shoes and 500 hats or $10,000 in cash – which the locals claimed they did not have. There was no shoe factory in Gettysburg, as the Confederates wrongly had believed. While Early remonstrated with the local leaders, his men ransacked homes, raided shops and took liquor from wherever they found it. The Confederates also stripped the Gettysburg people of their horses and mules, if they were fortunate enough to find them.<sup>7</sup> <br /> <br /> Elizabeth Thorn, expectant with her fourth child and missing her husband who had enlisted to fight for the Union, was so frightened by the sight and noise of the invaders that she fainted. “<em>They fired off their revolvers to scare people</em>,” she said. “<em>They chased people out and…jumped over fences</em>.” When they strode to Elizabeth’s house, which was the gatehouse of the Evergreen Cemetery, they asked for food – of which they were all clearly in need. Elizabeth and her aged mother quickly complied. “<em>They said we should not be afraid of them</em>,” Elizabeth remembered, “<em>they were not going to hurt us like the yankeys </em>[sic]<em> did their ladies</em>.”<sup>8</sup> <br /> <br /> Not all civilians were frightened of the Confederates. A small but significant minority of Copperheads – Northern people who supported the Confederacy – lived in and around Gettysburg. A few helped the Southerners with information. In addition to these, there also those living in the county who were devout conscientious objectors, mostly Pennsylvania Dutch farmers and Mennonites. They refused to help either side and firmly wished to be left alone. <br /> <br /> The Confederates had not come to stay. The following day they pulled out for York, burning two railroad bridges on their way. On Sunday, June 28, Early’s troops reached York, and the Union army wended its way closer to Pennsylvania. <br /> <br /> At three a.m. on Sunday, June 28, George Meade was awakened in his tent by Colonel James Hardie of the War Office. Hardie said that he “<em>had come to give him trouble</em>”, and Meade thought he was under arrest. Hardie lit a candle and told him that Lincoln had chosen General Meade to be the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Meade objected; he wanted to refuse the post, but Hardie insisted that it was an order. Meade hastily rose to dress, and commented, “<em>Well, I’ve been tried and condemned without a hearing, and I suppose I shall have to go to the execution</em>.”<sup>9</sup> <br /> <br /> General Meade was the seventh commander of the Army of the Potomac in the two years of the war. All of his former commanders had met with disaster to their careers. Meade expected the same treatment. He ordered the army northward with all possible speed.<br> Just hours later, Henry Harrison, a spy, approached General Longstreet’s headquarters near Chambersburg. The word of Meade’s rise to command had reached the newspapers, and Henry Harrison spread the news to Longstreet. Harrison also related that the entire Union army was on the march, heading toward Gettysburg. Lee was aghast that they had been surprised. “<em>Where on earth is my cavalry</em>?” he asked.<sup>10</sup> <br /> <br /> Soldiers from both sides of the conflict remembered the march toward Gettysburg as one of the most grueling. “<em>I never suffered more in my life than I did on this march</em>,” one Union soldier recalled.<sup>11</sup> <br /> <br /> On Tuesday, June 30, the citizens of Gettysburg were overjoyed to see men in blue riding into their town. They were John Buford’s Cavalry Division. As the horse soldiers rode northward on Washington Street, a group of Gettysburg girls rushed to greet them with water, food, flowers, and song. The men heartily thanked them. “<em>They were Union soldiers and that was enough for me, for I then knew we had protection</em>,” Tillie Pierce remembered.<sup>12</sup> <br /> <br /> John Buford, the Kentucky- born general of these troops, wasted no time becoming familiar with the land and the information he gleaned about the Confederate troops nearby. One Gettysburg youth saw the general near his headquarters, the Eagle Hotel, on Chambersburg Street. “<em>General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me</em>,” he said, “<em>entirely alone, facing to the west and in profound thought</em>.”<sup>13</sup> <br /> <br /> The Battle at Brandy Station, in the recent past, was only a precursor to what Buford knew was coming. The terrific storm of battle was going to occur, as all the elements were about to combine. Buford knew it, and he committed to it at that moment.<br> The general wrote dispatches to General Meade, the army commander, and John Reynolds, the wing commander immediately south with the closest Union infantry troops. He then told his men to warn the populace, and tell them to leave if they could. “<em>Acting on the advice of soldiers, many people had packed some belongings and left town</em>,” Sallie Myers wrote. “<em>Others, like the Myers family, did not</em>.”<sup>14</sup> <br /> <br /> “<em>As we lay down for the night</em>,” Tillie Pierce remembered, “<em>little did we think what the morrow would bring</em>.”<sup>15</sup> <br /> <br /> The following day, Wednesday, July 1, a dark and leaden storm unleashed its fury upon the town of Gettysburg – and its ramifications are still felt 158 years later.</p> <p><em>Sources: Alleman, Tillie Pierce. <u>At Gettysburg: Or What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle</u>. New York: W. Lake Borland, 1889 (reprint: Gettysburg: Shriver House Museum, 2015). Aughinbaugh, Ellen, Civilian Accounts File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Cleaves, Freeman. <u>Meade of Gettysburg</u>. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960. Coddington, Edwin B. <u>The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command</u>. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Foote, Shelby. <u>The Civil War: A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian</u>. Vol. 2. New York: Vintage Books, 1986 (reprint: first published by Random House, 1963). Longsteet, Gen. James CSA. <u>From Manassas to Appomattox</u>. New York: William S. Konecky, Associates, 1992 (reprint). Rhodes, Elisha Hunt. <u>All For The Union: The Civil War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes</u>. New York: Orion Books, 1985. Rogers, Sarah Sites. <u>The Ties of the Past: The Gettysburg Diaries of Salome Myers Stewart</u>. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1996. Skelly, Daniel, Civilian Accounts File, ACHS. Thorn, Elizabeth. “A Woman’s Thrilling Experiences of the Battle of Gettysburg.” Thorn Civilian Accounts File, ACHS.</em></p>](https://lirp.cdn-website.com/fd5107cc/dms3rep/multi/opt/Buford+-+Staff+lc-1920w.jpg)