As the sun glared in the afternoon sky on July 3, 1863, Seminary Ridge south of Gettysburg was teeming with soldiers anxious and eager for the assault they were about to make upon the Union center line. The men in Major General George Pickett’s Division, however, were tired. They had been awake since 2 a.m. that morning and walked several miles before reaching their current destination. Some ate their meager lunch, some stretched out and slept among the trees that bordered the ridge. Of Pickett’s three brigade commanders, one had gray hair to match his uniform. He was 46-year-old Lewis A. Armistead, and he was ready to lead his men into what would be his most memorable – and last – battle on earth.

Lewis Addison Armistead was a Virginian by heritage, even though he was born in North Carolina. His father, Walker Keith Armistead, had been born into a family of military men – one of five brothers. Lewis’s uncle, George Armistead, gained fame for protecting Fort McHenry in Baltimore during the War of 1812. A second uncle, for whom the younger Armistead was named, fell at the Battle of Fort Erie. Keith, Lewis Armistead’s father, graduated from West Point in 1803, and fought in Canada during the War of 1812. He remained in the military throughout his life, and was second in command of the Federal army when his son, Lewis, was born in 1817. It was a natural step, then, for Lewis to follow his heritage with a military career.1

Lewis Armistead was accepted to West Point in 1834. He was expelled two years later, after smashing a plate over the head of the recalcitrant Jubal Early, who had insulted Armistead.2

Through his family connections, the young Armistead was accepted into the army in 1839. Serving with the 6th U.S. Infantry, he fought in the War with Mexico, and ended that war with the rank of captain. After the war, he continued to serve for fourteen years on the American frontier.3

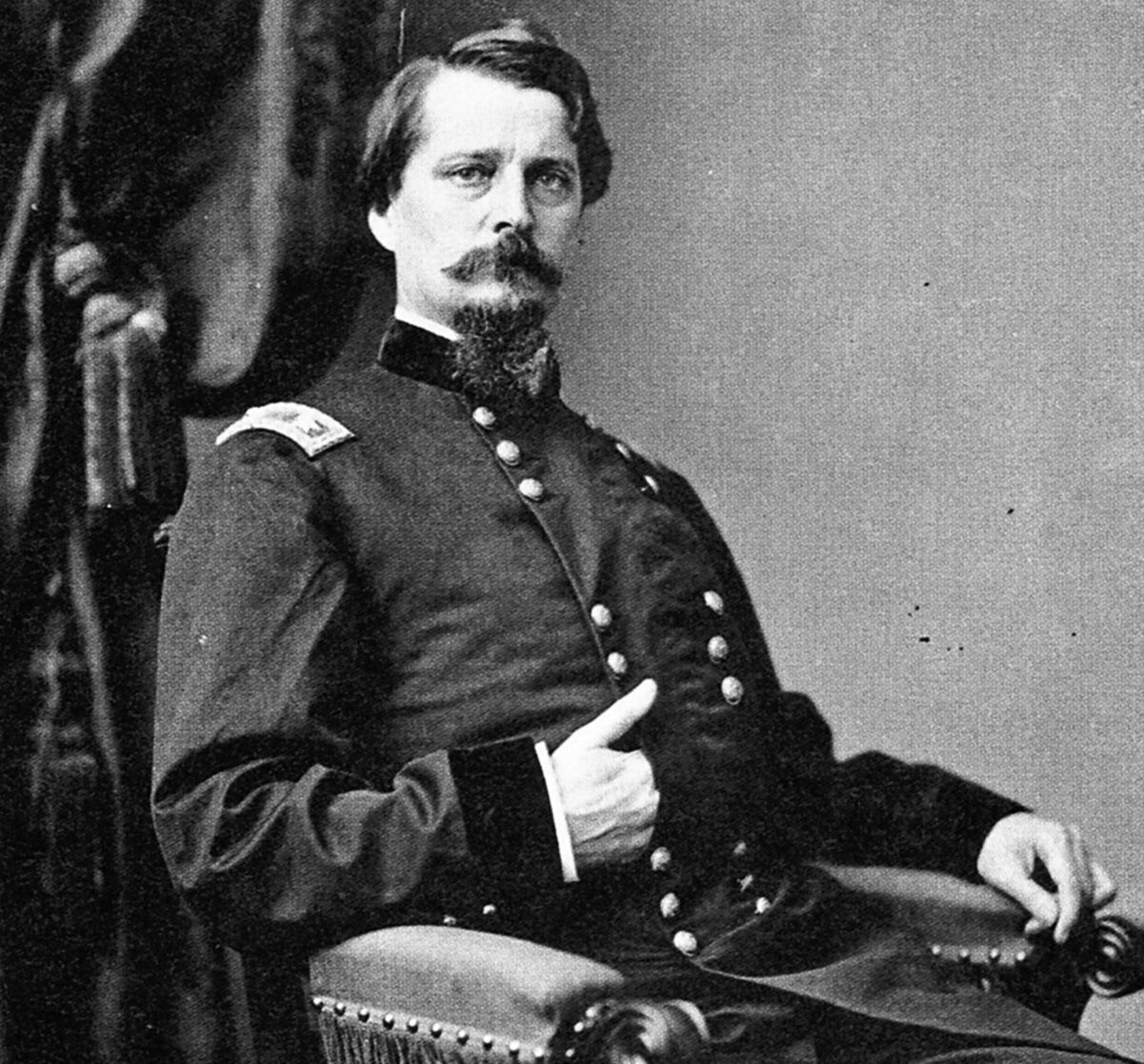

When the clouds of war brooded on the horizon, and war was imminent between North and South, Armistead was in Los Angeles, an outpost along the Pacific Coast. The night before Armistead left for Virginia to fight for the Confederacy, his friend who was remaining for the Union, Winfield S. Hancock, held a soirée at his home in the City of Angels. Mrs. Hancock remembered that Captain Armistead placed his hands on Hancock’s shoulders, and with tears on his cheeks declared, “Hancock, good-by; you can never know what this has cost me.”4

Armistead left California on foot and walked to Austin, Texas, where he took a train to Richmond. In April 1861, he was made commander of the 57th Virginia Infantry. Within a year, he was promoted to brigade command, and led his men in the Peninsula Campaign. With every battle he was “displaying everywhere conspicuous gallantry,” constantly demonstrating “his coolness under fire.”5

His men were devoted to him. “He was a strict disciplinarian,” one of his soldiers remembered, “but was never a martinet.” Another testified that Armistead “

was a Virginian to his heart’s core.”6

Armistead led his brigade through the battles at Seven Pines, Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, and Antietam. Throughout the year of 1862, many of his men were lost to wounds and death. New recruits came to take their places, and by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, a significant few were still in the ranks from the days of the beginning of the war.

At Gettysburg, Armistead’s brigade included the 9th, the 14th, the 38th, the 53rd, and the 57th Virginia Infantries.

When Armistead’s Brigade arrived at Gettysburg on the morning of July 3, 1863 with the rest of Pickett’s Division, they were ready to fight. Between their position on Seminary Ridge and their planned assault on Cemetery Ridge lay a field that spanned nearly a mile wide. As the men made their meager meals or lay prone in the woods to rest before the battle, General Armistead asked a member of his staff, Walter Harrison, to report to General Pickett and ask “whether he wished him to push out, and form a line in the front of the right of Heth’s Division, or to hold his position in the rear for the present.” It seems that Armistead was determined to earn glory for his men that day.7

Colonel Harrison was unable to locate Pickett, but found General Longstreet instead. Longstreet replied, “Never mind, Colonel, you can tell Gen. Armistead to remain where he is for the present, and he can make up his distance when the advance is made.”8

Shortly after Harrison returned to Armistead with the message, the terrible cannonade began. “Such a tornado of projectile it has seldom been the fortune or misfortune of anyone to see,” Harrison remembered. “The atmosphere was broken by the rushing solid shot, and shrieking shell; the sky, just now so bright, was at the same moment lurid with flame and murky with smoke. The sun…was obscured with clouds of sulphurous mist, eclipsing his light, and shadowing the earth as with a funeral pall.”9

Armistead ordered his men to stay down. His calm demeanor helped his men to remain still and silent. After the shelling ceased, Pickett’s Division was ordered forward. Armistead’s Brigade stood in support of the two brigades to his front: those of Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett and Brig. Gen. James Kemper. As Armistead’s men lined up behind Kemper’s troops, the old brigadier pointed to his men and said to Kemper, “Did you ever see a more perfect line than that on dress parade?” He was justifiably proud of his men.10

As the troops moved forward out of the woods of Seminary Ridge, Armistead gave a final admonishment to his brigade: “Men,” he shouted, “remember your wives, your mothers, your sisters, your sweethearts

!” It was enough – “They soon caught his fire and determination, and resolved to follow that heroic leader until the enemy’s bullets stopped them.”11

“Between us and Cemetery Ridge was a field…open…not a tree, not a stone to shelter one man from the storm of battle…Before us, moving on like waves of the sea, marched Garnett and Kemper, their battle flags flashing in the sunlight.” Immediately the cannon from the Federal line, from Little Round Top to Cemetery Ridge, began to fire. As the Confederate advance continued, the fire grew more pointed and more violent.12

As the Union artillery hit Pickett’s Division, large gaps opened in the advancing line. The brigades and their commanders closed ranks and continued. To their left, two more divisions also advanced with temerity and determination.

Between the ridges, the field was bisected by the Emmitsburg Road, a thoroughfare about three hundred yards from the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. A large split-rail fence lined the road – and the Confederates had no choice but to climb the fence and cross the road to reach their objective. Once the men in gray reached the Emmitsburg Road, they were within range of the Federal muskets. Large sheets of flame erupted from the rifles as the Federals found easy marks on the advancing troops.

As Armistead’s Brigade drew close to the road, General Kemper rode back to Armistead, who was on foot. “Hurry up,” Kemper said to Armistead. “I am going to charge those heights and carry them and I want you to support me.”13

“I’ll do it,” Armistead replied calmly, as he led his men through the furious field.14

While Garnett and Kemper rode during the charge, Armistead walked in front of his men. In order that they could see him, the general removed his black felt hat and placed it on the tip of his sword. He held it up as he ordered the “double-quick

” and began to run. “The sword pierced through the hat, and more than once it slipped down to the hilt...the old hero would hoist it again to the sword’s point.” All the while, a hailstorm of bullets rained upon them, felling many of Armistead’s brigade.15

“At the critical moment,” one soldier from the 53rd Virginia recalled, “Armistead himself with his hat on the point of his sword…that his men might see it through the smoke of battle rushed forward, scaled the wall and cried ‘Boys give them the cold steel!’ By this time the Federal host lapped around both flanks and made a counter advance in their front and the remnant of those three brigades melted away.”16

Armistead crossed the stone wall with a portion of his men – all those who had not yet fallen. In an attempt to turn the rising blue tide, he reached a Union battery – commanded by the recently slain Alonzo Cushing – and attempted to turn one of the big guns on the Federals.

“A squad from twenty-five to fifty Yankees around a stand of colors to our left fired a volley…at Armistead and he fell forward,” remembered a sergeant from the 14th Virginia. “

General Armistead did not move, groan, or speak…so I thought he had been killed instantly.”

17

Armistead managed to raise up and gave the Masonic signal of distress. A Union officer, Henry Bingham, also a Mason, hurried over to the fallen general. He noted that Armistead was “seriously wounded, completely exhausted, and seemingly broken-spirited.” Shot in the chest and arm, Armistead inquired about his friend, General Winfield S. Hancock – his friend from the days of the frontier. He knew that Hancock was commanding the line, and was certain that his old friend would treat him courteously. When Armistead learned from Captain Bingham that Hancock was seriously wounded, he was stricken with sorrow at the news.18

Armistead was carried to the Union field hospital at the George Spangler Farm, where he was placed in the summer kitchen. He lingered for two days, and died on July 5 – the day after Lee’s army vacated Gettysburg. He was embalmed and buried, and soon his relatives came to retrieve him. He was buried next to his famous Uncle George, the hero of Fort McHenry, in St. Paul’s Churchyard in Baltimore. The two Armisteads will forever be linked to the battles that made them famous – one for a great victory, the other for a terrible defeat.19

Pickett’s Charge is forever remembered as the battle that caused the beginning of the end for the Confederacy. Like General Armistead, countless souls never fought another battle, and Lee could never recover from their loss.

“What a field this was!” remembered one Confederate. “We came upon numberless forms clad in gray, either stark and stiff or else still weltering in their blood…Turning whichever way we chose, the eye rested upon human forms lying in all imaginable positions.”20

“Poor Armistead,” lamented Colonel Walter Harrison, “a better, braver soul never ascended to heaven.”21

The Virginian born in Carolina, who could never fight against his own, proved his determination to serve to the last at the sanguinary field where the South made a gallant but hopeless attempt, at the place called Gettysburg.