Cadmus Wilcox: "Dear to the Hearts"

by Diana Loski

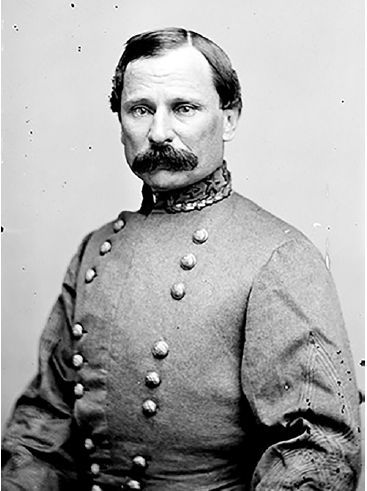

Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox

(National Archives)

It was not unusual that during funerals for Civil War generals that both Union and Confederate veterans attended in post-war years to pay their respects. For the final tribute to one who had worn the gray, however, the eight pall bearers consisted of four Union and four Confederate soldiers – evenly united in their grief at the passing of one who was beloved by friends in the North and the South. Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox, a man who had served in Lee’s army from First Manassas to Appomattox, managed to keep his many friendships through the worst conflict America faced.

Cadmus Wilcox was born in Wayne County, North Carolina on May 29, 1824, the son of Reuben and Sarah Wilcox. He and his older brother, John, soon moved with their parents to Tennessee, where they grew up. Cadmus attended college in Nashville for a time, until he was accepted at West Point in 1842. He graduated from that academy in 1846, just in time to fight in the Mexican War.1

Wilcox was recognized on multiple occasions during that war for courage under fire, fighting in the Battles of Vera Cruz and Cerro Gordo. He earned a promotion to 1st Lieutenant after the Battle of Chapultepec, which gave the American forces the capital city of Mexico. After the war, he taught military tactics at West Point, and penned a book on weaponry, entitled Rifles and Rifle Practice, published in 1859.2

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Captain Wilcox resigned from the U.S. Army and offered his services to the Confederacy. He began the war as Colonel of the 9th Alabama Infantry, and fought in that capacity at the Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) in July. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in October of that year, commanding a brigade of regiments from Alabama, Virginia, and Mississippi. As a brigade commander, he fought in the Peninsula Campaign, where his troops lost heavily at Seven Pines. The losses of Wilcox’s Brigade “exceeded all from Longstreet’s Corps during the Seven Days’ Battles.”3

Wilcox was ill during the Battles of 2nd Manassas and Antietam. He was, however, engaged in the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville as part of General Jackson’s corps. He continued to hold the rank of Brigadier General through the Battle of Gettysburg, fighting there on July 2, 1863.4

Wilcox’s brigade, which consisted of the 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 14th Alabama infantries, formed part of Richard Anderson’s Division, in A.P. Hill’s Corps. Wilcox and his men arrived in Gettysburg via Cashtown, and took up their position on Seminary Ridge to the right of Perry’s Florida Brigade on July 2.

During the early afternoon, Wilcox was told by General Anderson to watch for any opportunity to take any ground vacated by the Federals. Soon, due to the redeployment of General Sickles and his Federal Third Corps to places that surprised the men of the South, places like the Peach Orchard and the Wheatfield were suddenly in the picture.

Part of Wilcox’s Brigade deployed on Seminary Ridge in Pitzer’s Woods, with their left touching Spangler’s Woods. A large field lay to their front, and Wilcox could see Union cannon and skirmishers. He did not know who occupied the woods, and felt uneasy, as Federal troops, possibly outnumbering his men, could be hidden there.5

Like many Confederate records, there is little information on Wilcox’s Brigade at Gettysburg.

Wilcox and his troops supported Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade in their attack on the Peach Orchard. Obeying orders, Wilcox led his men through the Peach Orchard, near the Klingle Farm. He saw an opportunity as he spied Cemetery Ridge. There were few soldiers there, as most of them had rushed to the aid of General Sickles, whose men were in danger of obliteration in their untenable positions away from the main Union line.6

Union General Winfield S. Hancock, riding on Cemetery Ridge, also noticed the gap in his position. Through the smoke and intense cannonading, Hancock rode up to the First Minnesota Regiment, exclaiming, “My God! Are these all the men we have here?” He quickly addressed Colonel William Colvill of the Old First and pointed to Wilcox’s Brigade. “Advance, Colonel,” he said, “and take those colors.”7

The men of the First Minnesota, less than three hundred strong, were considered the very first Union regiment to offer their services at the start of the Civil War. They were battle-hardened, and immediately obeyed the order. There were reinforcements coming from Culp’s Hill, but Hancock knew that Wilcox’s forces needed to be stalled, or they would likely reach and occupy the Union line.

When the Minnesotans rushed toward Wilcox’s men, the clash was fierce. Through the smoke and chaos of battle, the surprise counterattack stopped the Confederate brigade, as they had not met any stiff opposition until that time. Unable to see through the smoke and the marshy swale in their path, Wilcox’s men halted and did not counterattack. Both sides suffered significant casualties.8

When questioned by General Lee the next day about reaching the Union line, Wilcox replied, “The problem is not getting there. The problem is in staying there.”9

While Wilcox’s Brigade is usually not recognized as part of Pickett’s Charge, as part of Anderson’s Division, according to Wilcox, his brigade did participate in that fateful attack.

“With reference to the attack of the 3rd distant,” he wrote in his official report, “early in the morning, before sunrise, the brigade was ordered out to support artillery under the command of Colonel Alexander…My men had had nothing to eat since the morning of the 2nd and had confronted and endured the dangers and fatigues of the day. They nevertheless moved to the front as ordered.” They endured the exposure “to the solid shot and shell” of the Union cannonade. As soon as Pickett’s Division advanced, “three staff officers in quick succession…gave me orders to advance to the support of Pickett’s Division. My brigade, about 1200 in number, then moved forward.”10

Wilcox’s Brigade moved across the open field, “exposed to a close and terrible fire of artillery….I ordered my men to hold their ground…After some delay, not getting any artillery to fire upon the enemy’s infantry that were on my left flank, and seeing none of the troops that I was ordered to support, and knowing that my small force could do nothing save to make a useless sacrifice of themselves, I ordered them back.”11

In less than an hour, Pickett’s Charge had ended, and the Battle of Gettysburg was over. General Wilcox spied General Lee, who was watching the survivors return to Seminary Ridge. “General Lee,” Wilcox said, as tears streamed down his cheeks, “I came into Pennsylvania with one of the finest brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia, and now my people are all gone. They have all been killed.”12

General Lee turned to Wilcox and said solemnly, “It is all my fault, General.”13

The epic struggle had now turned, and the Army of Northern Virginia would never again be on the offense. Hoping to outlast the Lincoln Administration, the Confederates fought through the dark months of 1864. General Wilcox inherited a division with the death of General Dorsey Pender, who had been mortally wounded at Gettysburg. He led the former Pender’s Division through the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Petersburg.

Wilcox received another significant blow in February of that year. His brother, John, who served in the Confederate House of Representatives, died of an apparent cerebral hemorrhage at his Richmond boarding house. Married with children, John Wilcox's sudden death brought much grief to his family, and to his brother who had already suffered from the losses of his men at Gettysburg.14

The war wound to a close at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. General Wilcox was present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia with his division. He had survived the conflict, and looked to the future.

After the war, General Wilcox was offered a commission in the Egyptian army. At age 41, Wilcox still had many years ahead of him. He declined the offer, opting instead to stay in the United States to take care of his widowed sister-in-law and her children. Wilcox, who never married, spent the rest of his life assisting his brother’s family.15

Wilcox went to work for the railroad, and in 1886 he was appointed by President Grover Cleveland as Chief of the Railroad Division of the United States. He had already made his residence in Washington, D.C. for his earlier position with the railroad in 1884. Overseeing the expansion of the railroad, Wilcox managed, in his free time to write another book, entitled History of the Mexican War. It was published after his death, in 1892.16

On Thanksgiving Day in 1890, Cadmus Wilcox left his home in the District to survey an excavation for the laying of rails near the corner of 14th and G Streets in Washington. The aging general tripped and fell into the excavation, hitting his head on the concrete. He was taken home and examined by a doctor. A few days later, on December 2, 1890, Cadmus Wilcox died early in the morning of a stroke and its ensuing cerebral hemorrhage caused by the fall. He was 66 years old.17

The funeral of Cadmus Wilcox was filled with many mourners. One of them was Confederate general Harry Heth. “I know of no man of rank,” he wrote, “who participated in our unfortunate struggle who had more warm and sincere friends, North or South, than Cadmus Wilcox, over whose sad demise more sincere tears were shed.”18

“He was dear to the hearts of many old soldiers in this country,” wrote a Mississippi veteran, “and his death will be sincerely mourned.”19

The old general’s funeral took place at St. Matthew’s Church in Washington, D.C. General Joe Johnston was in attendance, accompanying John Wilcox’s widow and her children. The pallbearers included Generals Harry Heth, Field, and Felix Robertson, and Colonel Harvey of the South, and General Benjamin Butler, with Senators Gibson and Vance, who were Union veterans.20

Cadmus Wilcox was “one of the very few surviving generals of the late Confederacy”, who never severed his friendships with those who were divided in their causes. One who preceded him in death was his good friend Ulysses S. Grant. Wilcox had served as Grant’s best man when he married the former Julia Dent in St. Louis.21

Because of soldiers, North and South, who remained true to their old friendships, forgiveness and looking forward to the future was made possible after the terrible four-year war that took a horrendous toll on human lives. Though he fought valiantly for the doomed Confederacy, Cadmus Wilcox remained a friend, and an example, to all.

Sources: 1st Minnesota File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). American Battlefield Trust: battlefields.org/CadmusWilcox. The Austin American Statesman, Dec. 4, 1890. The Chattanooga Republican, Dec. 7, 1890. Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol. V. New York: D. Appleton & Sons, 1889. Evans, Clement A. Confederate Military History. Vol. X. Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. The Evening Star, Washington D.C., Dec. 4, 1890. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Port Gibson Dispatch, Mississippi, Dec. 10, 1890. Rollins, Richard, ed. Pickett’s Charge! Eyewitness Accounts. Redondo Beach, CA: Rank & File Publications, 1994. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1994 (reprint, originally published in 1959). Wilcox's Brigade, Participant Accounts File, GNMP. Historical newspapers accessed through newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Drake, p. 536. Warner, p. 337.

2. Port Gibson Dispatch, Dec. 10, 1890.

3. Evans, p. 342.

4. American Battlefield Trust, battlefields.org/CadmusWilcox.

5. Pfanz, p. 355.

6. Ibid., p. 366.

7. Ibid., p. 410.

8. 1st Minnesota File, GNMP.

9. Wilcox OR, p. 619. Participant Accounts File, GNMP.

10. Wilcox OR, p. 619. Quoted in Rollins, pp. 146-147.

11. Rollins, p. 147.

12. Ibid., p. 178. From a letter by James Johnson, a soldier in Perry’s Florida Brigade.

13. Ibid.

14. The Richmond Dispatch, Feb. 8, 1864.

15. Drake, p. 536.

16. Warner, p. 337. Drake, p. 536.

17. The Chattanooga Republican, Dec. 7, 1890. The Evening Star, Dec. 4, 1890. Warner, p. 338.

18. American Battlefield Trust: battlefields.org/CadmusWilcox.

19. The Port Gibson Dispatch, Dec. 10, 1890.

20. The Evening Star, Dec. 4, 1890.

21. The Austin American Statesan, Dec. 4, 1890.