Colonel E.P. Alexander: The Noble Warrior

by Diana Loski

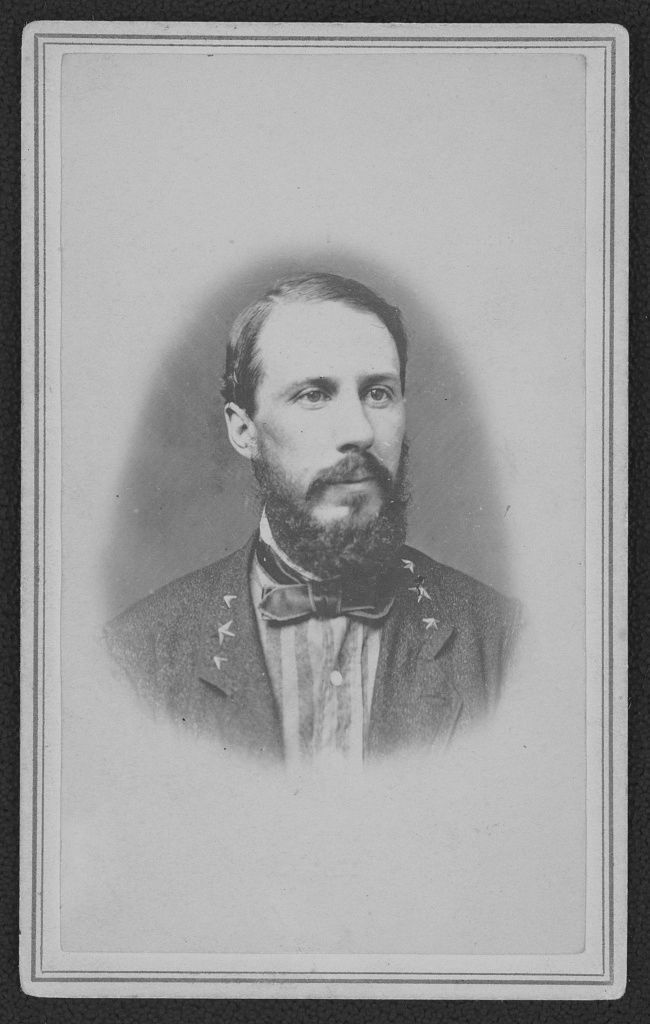

Colonel E.P. Alexander

(Library of Congress)

The future cannoneer, who used his middle name as his eponym, was born to a slaveowner, Adam Leopold Alexander, and his wife, the former Sarah Millhouse, in Washington, Georgia, on May 26, 1835. Porter’s great-grandfather, also an Adam Alexander, emigrated from Inverness, Scotland to Georgia just before the American Revolution. The family held a special affection for their native land, and many of them, Porter included, named their homesteads Inverness.1

Porter was accepted to West Point in 1853 and graduated third in his class in 1857. He excelled in mathematics and engineering, and remained at West Point as an instructor for those subjects. He left briefly to serve in the Utah Expedition in 1858, then returned until called west again. Just prior to the eruption of Civil War in 1861, Lieutenant Alexander was in Oregon for military defenses of the coast, along with his immediate commander, Lieutenant James McPherson. Their unit had boarded a steamer to San Francisco, to fortify the island of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay. While there, the news of Fort Sumter reached them, and they all knew war was imminent. Newly married to a Virginia belle named Elizabeth Mason, Alexander agonized over his dilemma. Should he stay in the Union, where he had pledged his allegiance, or should he resign and go home to his family and friends, all of whom were siding with the Confederacy?2

James McPherson tried to dissuade Alexander from joining the Confederacy. He said, “If you must go, I will give the leave of absence. But don’t go…if you are willing to keep out of the war on either side, you can do so. General Totten likes you and wants to keep you in the Corps….Going home you have every personal risk to run, and in a cause foredoomed to failure.”3

As it would have likely turned out, Alexander would have eventually had to join the fight, on one side or the other. He realized it and told McPherson, “My people are going to war. They are in deadly earnest, believing it to be for their liberty. If I don’t come and bear my part, they will believe me to be a coward. And I shall not know whether I am or not. I have just got to go and stand my chances.”4

McPherson acquiesced and signed the resignation. It was May 1, 1861. Porter Alexander officially joined the Confederacy as a captain of engineers. He served as a signal officer on the staff of General Pierre G.T. Beauregard, and was present at the Battle of First Manassas.

Alexander was soon transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded at the time by General Joseph Johnston. He served under General Longstreet as his Chief of Ordnance, and was later in charge of a reserve battalion in Longstreet’s Corps. During the Peninsula Campaign, Alexander used his engineering skills to find the presence of the Union army, even ascending in a hot air balloon in a reconnaissance mission.6

General Johnston was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines in late May 1862. As his wound was severe, he taken from command and replaced by General Robert E. Lee. Alexander was pleased that Lee was in charge, as Lee had come directly from Richmond as an advisor to Jefferson Davis. “The chances of a successful campaign against McClellan had increased greatly when Johnston fell,” he wrote. “Lee would be able to bring this about more effectively.” He added that Lee’s arrival “did not at once inspire popular enthusiasm.” That sentiment would soon change.7

The Confederates achieved many victories with General Lee, including the successful end of the Peninsula Campaign, and the battle of 2nd Manassas later that summer. Lee’s men did not fare as well at Antietam, but that changed in December with the Battle of Fredericksburg. Lee’s troops took the high ground at Marye’s Heights, while the Union troops under General Burnside were still crossing the Rappahannock. Alexander, who commanded a Reserve Artillery Battalion in Longstreet’s Corps, had ample time to place his guns. He arranged the artillery so that every part of the field was covered. He told General Longstreet, “We cover that ground so well that we will comb it with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.” Alexander was correct. The Union forces fell mightily at Fredericksburg.8

Alexander began the year 1863 with high hopes for a Southern victory. He witnessed the Mud March by Burnside’s beleaguered troops, and was present at the Battle of Chancellorsville. When Lee ordered his army northward into Pennsylvania, Alexander understood the reasons. “Each summer campaign in Virginia marked a Confederate crisis…it was impossible as long as the war spirit ruled in the North…It was now for Lee to take the offensive – a role appealing strongly to his disposition.”9

It is mostly to the records kept by Colonel Alexander that we know the disagreement that occurred between Generals Lee and Longstreet at Gettysburg. After a portion of the armies clashed on the first day, Longstreet wanted to deploy away from Gettysburg nearer Washington to force the Federals’ hand, especially with a new general – George Meade – at the helm. Lee insisted that they fight at Gettysburg, because “If he is there to-morrow, I shall attack him.”10

Longstreet replied, “If he is there to-morrow, it will be because he wants you to attack him.”11

Alexander’s Battalion, as part of Longstreet’s Artillery Reserve, was active during the second day against Sickles’s Federal Third Corps in the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield. In the ensuing melee, Alexander was slightly wounded in the leg as a piece of shrapnel ripped through his trousers. When the Confederates pressed the Union troops from their position in the Peach Orchard, Alexander’s cannoneers quickly rushed ahead, taking their position on the Emmitsburg Road. To the dismay of all men in gray, they saw that the Union line on Cemetery Ridge held. The victory was not yet complete.12

The next day, July 3, would make E.P. Alexander’s name inscribed in the history books. Lee’s Chief of Artillery, William Pendleton, was actually a crony of Lee and Davis, and past his prime. When Longstreet was called upon to lead the attack upon the Union center on Cemetery Ridge, he wanted someone trustworthy to support the infantry with precise artillery. Colonel Alexander, at age 28, was chosen for the task. Longstreet apprised Alexander that he, the young artillerist, would make decisions upon which the three divisions, including Pickett’s would charge. The news daunted the young man from Georgia. “Until that moment,” he remembered, though I fully recognized the strength of the enemy’s position, I had not doubted that we would carry it, in my confidence that Lee was ordering it. But here was a proposition that I should decide the question. Overwhelming reasons against the assault at once seemed to stare me in the face.”13

He turned to Brigadier General Wright, who had made an attack on the Union center late in the day on July 2. He asked, “ Is it as hard to get there as it looks ?” Wright answered, “ The trouble is not in going there….The trouble is to stay there after you get there.”14

What neither commander realized was that the evening before, General Meade had realized Lee’s plan – an old Napoleonic maneuver. Lee and Meade, both older generals, had been introduced to Napoleonic tactics before those maneuvers became outdated. Before Meade, the generals who had opposed Lee were all younger men who had not learned these antiquated tactics. But Meade knew. When Lee hit the Union flanks on July 2 and had failed in securing them, Meade believed, correctly, that Lee would attack his center line. Unlike July 2, it would be much more difficult to even reach the center, with a plethora of Union troops waiting for them to attack.

Alexander lined up his guns and at “1 p.m. by my watch”, on Friday, July 3, a lone missile flew across the field into the Union line and exploded. A barrage followed. Alexander had about 75 artillery pieces aimed at Cemetery Ridge. The Federal guns answered, and for about two hours an artillery battle ensued.15

While Alexander’s guns found their marks early in the fight, the excessive smoke rendered the field, and the Union targets, practically invisible. Additionally, recent rains had created a morass of mud. When the wheels of the carriages recoiled, they became embedded in the mud. Unable to see, the cannoneers did not appropriately change the range to allow for this unforeseen predicament, and soon the missiles sailed over the heads of the soldiers on Cemetery Ridge, detonating far behind them.

Alexander remembered that “More guns had been added to the Union line than at the beginning, and its whole length, about two miles, was blazing like a volcano.” He was now low on ammunition. He sent a note to Pickett, “Come quick or my ammunition will not let me support you properly.”16

After a brief interval, the men in gray and butternut emerged from the woods on Seminary Ridge. As Alexander’s guns could only help but a little, he watched as the Union guns tore through Pickett’s lines. In less than an hour the charge had failed, and the survivors – who were few in comparison – retreated back to Seminary Ridge. Alexander, who retired his guns, recalled, “It was both absurd and tragic.” It was a fitting revenge, some Federals thought, for the Union losses at Fredericksburg.17

So far, the Confederate victory had eluded Lee’s army. Moreover, a staggering number of their soldiers had been killed or desperately wounded. While Lee never accurately acknowledged the number of killed, wounded and missing for his troops, one thing is certain. The Army of Northern Virginia would never be the same. The following year, 1864, added more attrition to Lee’s numbers. While the Union also lost heavily, the North had the population, and more soldiers enlisted, while the Southern men were not there to replenish the depleted army.

After Gettysburg, Alexander accompanied Longstreet to aid in the Battles of Knoxville and Chickamauga, although he arrived too late to Chickamauga to be personally engaged in the battle. In early 1864, E.P. Alexander was promoted to the rank of brigadier general – a rarity in either army for one serving with the artillery. He and Longstreet returned to the eastern theater and to Robert E. Lee. When Joe Johnston, who was fighting in North Carolina, asked for Alexander, Lee refused to allow the cannoneer to go. Jefferson Davis told one of Porter’s sisters that Alexander was “one of the very few whom Gen. Lee would not give to anybody.”18

Alexander was engaged at the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Petersburg. He was severely wounded at Petersburg, and was absent from the field for the rest of 1864. When Lincoln won reelection that November, it was the beginning of the death knell for the Confederacy. The end came at Appomattox, on April 9, 1865. Alexander was present that day, and spoke to General Lee in the minutes before he surrendered his army to General Grant. Alexander, when he saw the impossibility of victory and the specter of certain destruction, he suggested, “Then we have only choice of two courses. Either to surrender, or to take to the woods and bushes, with orders, either to rally to Johnston, or perhaps better, to the Governors of the respective States.”19

He added, “General, spare us the mortification of asking terms and getting that reply.”20

Lee asked him if he were to take his advice, how many would escape, to which Porter replied, “About two-thirds.” He was convinced that Lee would take his advice. He was wrong.21

Lee replied that they had to “consider its effect on the country as a whole.” Already demoralized, Lee said, the army would sink to groups of marauders or worse, making it worse for the country, and perhaps rendering the situation too difficult for the broken nation to recover. Alexander was rendered speechless. “He had answered my suggestion from a plane so far above it, that I was ashamed of having made it.”22

E.P. Alexander returned home to Inverness, in Georgia, to his wife, Betty, and their children, six in all: William, Adam, Emma, Lucy, Elizabeth, and Edward Porter Jr. All lived to adulthood.23

After the war, Alexander returned to the profession he knew best: mathematics and engineering. He taught for a time at the University of South Carolina, then began a foray into the railroad business, soon becoming a wealthy man. He served as the capital commissioner for the State of Georgia, until he was called for another duty. President Grover Cleveland requested that he settle a border dispute between Costa Rica and Nicaragua. He also traveled west to Oregon to engineer the navigation of the Columbia River.24

In 1890, Porter’s wife of forty years passed away. Shortly afterward, his daughter Lucy died. The losses devastated him and for many months he could not function. He finally decided to write to allay his grief. He wrote several treatises on artillery tactics, navigation, and civil engineering. He corresponded with veterans of Longstreet’s corps, and attempted to preserve the legacy of Lee’s old army. In 1894 he remarried and began work on his memoirs, entitled Military Memoirs of a Confederate . The work took many years to complete, published in 1907.25

Alexander’s memoir is succinct, with a genuine attempt at frankness and fairness. He criticized Lee at times, which drew the ire of some of the old Confederacy. He also praised where he felt it was deserved, from General Lee to some of the Union commanders, especially at Gettysburg. One of the recipients of his praise was George Meade.

Alexander fell ill with paralysis two years after completing his book. He struggled for a year, but never recovered. He died at his home, Inverness, in Augusta, Georgia, on April 28, 1910. He was buried with military honors in the city cemetery.26

“A career of greater usefulness could not be produced than that of the noble warrior and public citizen,” one journalist wrote.27

His full and eventful life can be traced to one afternoon in July, when all of his expertise was needed. Though Pickett’s Charge failed, Alexander, like the rest of the men of Lee’s army, had shown their nobility as soldiers and done their duty, at that place called Gettysburg.

A scene from Pickett's Charge, the Gettysburg Cyclorama

(Author photo)

Sources: Alexander, General E.P. Military Memoirs of a Confederate. New York: DaCapo Press, 1993 (originally published in 1907). Alexander Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Atlanta Journal, 28 April, 1910. Evans, Clement A. Confederate Military History (12 volumes) Vol. VII. Richmond: Confederate Publishing, 1899. The Macon Daily Telegraph, 30 April, 1910. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

End Notes:

1. The Macon Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr.,1910. The Atlanta Journal, 28 Apr. 1910.

2. Evans, p. 389. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 307. Alexander, pp. 6-7.

3. Alexander, p. 6.

4. Ibid., p. 7.

5. Warner, Generals in Gray , p. 3.

6. Evans, p. 389.

7. Alexander, p. 109.

8. Evans, p. 389.

9. Alexander, pp. 363-364.

10. Ibid., p. 387.

11. Ibid. Longstreet mentioned the same argument in his memoirs, reinforc ing Alexander's memory of the incident.

12. Pfanz, p. 310.

13. Alexander, p. 421.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., p. 423.

17. Ibid., p. 425.

18. Ibid., p. xxi.

19. Ibid., p. 604.

20. Ibid., p. 605.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Alexander Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

24. Evans, p. 389. Macon Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr. 1910.

25. Atlanta Journal, 28 Apr., 1910.

26. Ibid.

27. Macon Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr. 1910.