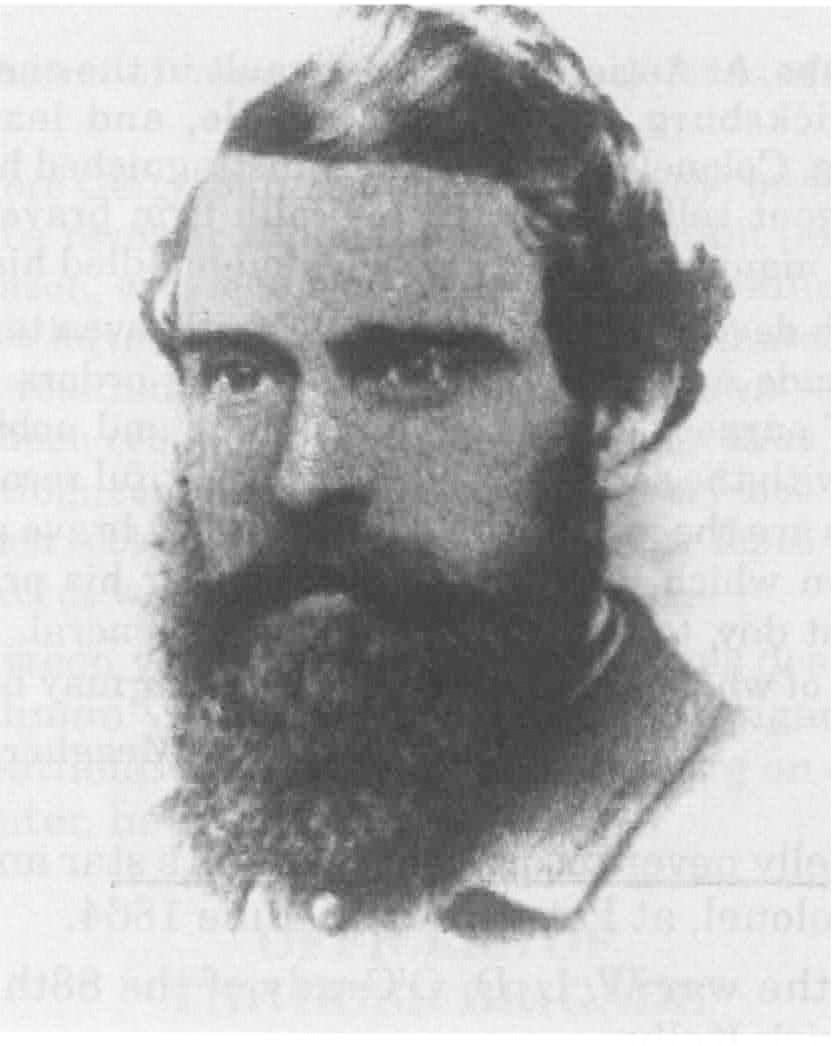

Colonel Patrick Kelly: Brave & Valiant to the Last

by Diana Loski

In order to escape the tyranny of old Europe, millions of Irish migrants came to the United States, and thousands enlisted during the Civil War to uphold the Union and its Constitution.

While there were also numerous Irish immigrants who fought for the Confederacy – the Louisiana Tigers being one of those units – the majority of Irish natives who made America their new home, escaping famine and oppression, eagerly enlisted in the Union cause. Undoubtedly the most famous was the Union’s Irish Brigade.

One of the members of this famous unit was a young widower and businessman who was living in New York City, bearing the quintessential Irish moniker of Patrick Kelly.

Patrick was born in the summer of 1822, at a hamlet called Castle Hackett (named for the ruined castle of the same name in the vicinity) in the county of Galway on the western coast of the Emerald Isle. He was the only son of Patrick and Mary McNully Kelly.1

On September 8, 1822, the infant was baptized in St. Peter’s church in Louth, a village near the border of Northern Ireland. Little is known of Patrick’s childhood, but the times in Ireland were tenuous, and the child and his parents likely had to go where work and food could be found.2

A few years later, a sister, Mary, was added to the family. When young Patrick was just nine years old, his father died, and his mother struggled to feed her two children as famine engulfed the Irish nation. With little education, Patrick was hired out as a laborer to help his mother and sister endure the devastating potato famine.3

Patrick courted and married his sweetheart, Elizabeth Burke, while still in Ireland. The couple set sail for the United States in 1850, along with Elizabeth’s two brothers, Michael and Patrick. If the couple had any children, none survived.4

Patrick and Elizabeth Kelly settled in New York City, where he established a mercantile shop on Eighth Street, called Decatur House. He also joined the local militia – and nurtured many friendships with fellow immigrants from his native land. They were a tremendous comfort to Patrick when his wife died after a long illness in 1858.5

Thomas Meagher, a fellow merchant, was one of Patrick Kelly’s close friends. Meagher was a well-respected revolutionary from Ireland who had been imprisoned for treason by the British, and sent to the Island of Tasmania, off the coast of Australia. Meagher fashioned an incredible escape by throwing himself into the sea and swimming in dangerous conditions to a small island, where he languished for days until he was rescued by a ship. He settled in New York and was greatly renowned for his tenacity.6

When war erupted between the North and South in 1861, Patrick, already in the local militia with Meagher, signed up for three-month’s service. He saw action as a private with the 69th New York militia at the Battle of First Manassas on July 21, 1861. When the term ended, Kelly returned to New York, and learned that Meagher was eager to form an Irish Brigade. Kelly, along with many other patriotic Irishmen who claimed the United States as their new home, enthusiastically complied. The Irish Brigade was officially recruited by the fall of 1861. Patrick was 39 years old.7

“He was not a large man to look at,” remembered one of the brigade. “He had the physique of a Hercules, broad and deep chested. He was handsome with a noble forehead, brilliant black eyes, fine nose, the blackest hair and beard…which is not uncommon among the people of Galway and Limerick…”8

On September 14, 1861, Kelly rose in rank to be the Lieutenant Colonel of the 88th New York Infantry, one of the three New York regiments that comprised the new Irish Brigade. The other regiments were the 63rd and 69th New York. Thomas Meagher was the commander of these zealous units.

The Irish Brigade, part of Edwin Sumner’s Second Corps in the Army of the Potomac, received their baptism of fire during the Peninsular Campaign. General George McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac at the time, attempted to take Richmond in the spring of 1862. When the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Joe Johnston, fell with a serious wound at the Battle of Fair Oaks (or Seven Pines) on May 31, Jefferson Davis replaced him with Robert E. Lee.9

As McClellan and Lee clashed over Richmond for seven deadly days on the Virginia Peninsula, the ensuing battles were named “The Seven Days Battles”. The engagements lasted from June 25 to July 1, 1862 and included battles at White Oak Swamp, Gaines’s Mill, Savage Station, Glendale, and Malvern Hill. In the heavy fighting, with Lee proving to be an aggressive defender, the Irish Brigade continuously rushed into the fray, losing nearly half of their number on the battlefields, including two hundred at Malvern Hill alone. Patrick Kelly and Thomas Meagher were in the front lines, on horseback. Miraculously, neither was hurt.10

Colonel Kelly, true to his native land, named his horse “Faugh a Ballaugh”, a Gaelic term that means “Clear the way.” The phrase was also the rallying cry for the Irish Brigade. While McClellan retreated, the Irish Brigade’s fame for their courage and ferocity in battle spread throughout the Union army.11

In July 1862, Abraham Lincoln, a friend of General Meagher, arrived to inspect the army and made a special visit to the camp of the Irish Brigade. The men in the ranks saw the President lift the battle-torn green flag of the 69th New York and kiss it. He murmured, “God bless the Irish flag!” His words endeared him to the Irish soldiers, and they remained devoted to the Union for the duration of the war, at a terrible cost.12

Kelly's native Ireland, near Galway

(author photo)

The Irish Brigade received needed additions to their number. Two regiments joined the New York regiments in the fall of 1862: the 116th Pennsylvania and the 28th Massachusetts. The Pennsylvania Irish joined the brigade at the Sunken Road at Antietam, where they lost heavily but gained the position. The 28th Massachusetts joined them just before Fredericksburg, where the Brigade lost half their rank and file on the slopes of Marye’s Heights.13

Lincoln relieved George McClellan of command weeks after the Battle of Antietam in the fall of 1862. He replaced the little Napoleon with Ambrose Burnside, who proved no better at command. In early 1863, Joe Hooker took over command of the army – and General Sumner resigned. He was replaced with Darius Couch in command of the Union Second Corps. After Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville, Couch resigned in disgust, and he was replaced with General Winfield Scott Hancock. After Chancellorsville, Thomas Meagher also resigned. Patrick Kelly replaced him as commander of the Irish Brigade. Meagher appealed to Lincoln to promote Kelly to the rank of brigadier general. For unknown reasons, Kelly never received his brigadier’s star.

By the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, the Irish Brigade numbered 530 men – approximately the size of a fairly large regiment in 1863. They had lost one thousand of their number the previous year. They were part of John Caldwell’s Division, Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps. The Irish men marched up the Taneytown Road and camped in a field a few miles south of town on the night of July 1, 1863. They rose at first light (about 4:30 a.m.) and completed their march. They deployed on Cemetery Ridge, according to orders.14

The Union line, shaped like a fish hook, was a good interior line with its center and flanks on high ground. That changed when General Dan Sickles moved his corps from the line out to places near the Emmitsburg Road: The Peach Orchard, The Wheatfield, and Devil’s Den. The Confederates gleefully attacked Sickles’s men and the Union line began to unravel. In a desperate attempt to stop the Confederate tide and save Sickles’s men from annihilation, General Hancock ordered General Caldwell’s Division of four brigades into the Wheatfield.

“About 5 PM received orders to march by the left flank,” Colonel Kelly wrote. Before they embarked, the brigade chaplain, Father Corby, requested time to give absolution. Kelly assented. They then “advanced in a line of battle through a wheat-field into a wood, in which was a considerable quantity of large rocks.” He described the Stony Hill on the southwestern fringe of the Wheatfield. Confederates from Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolinians were waiting for them behind the boulders. The Irish returned fire and stood their ground.15

The Irish muskets were buck and ball – which were excessively deadly at close range. With little time to reload, many on both sides fought hand-to-hand, clubbing one another with the butts of their muskets or using the bayonet. One Irish soldier believed that hour in the Wheatfield “was the hottest and sternest struggle of the war.”16

Kelly, like Meagher before him, remained at the front and in the midst of the fight. His presence and steady persistence, calling them, “brave byes” kept the resolve. One comrade recalled that “He possessed the true instincts and brilliant capacities of a high military leader.” Kelly formed a good defensive position bordering on the Rose Farm property, fighting against General Semmes’s Georgia troops as well as the Carolinians. St. Clair Mulholland, commander of the 116th Pennsylvania, notified Kelly that another Confederate brigade (Wofford’s) was in sight. To avoid being surrounded and captured, Kelly told the men to fall back in order. They reached Seminary Ridge, but 202 of their already depleted ranks had fallen on the Stony Hill.17

During the winter of 1863-1864, Patrick Kelly returned to New York City to recruit more troops for his depleted brigade. The following March, Lincoln named Ulysses S. Grant as commander of all Union armies. Grant had decided to lead Meade’s army and chase Robert E. Lee. At the same time, new enlistments for all regiments brought up the numbers of the depleted regiments. New recruits increased the Irish Brigade’s ranks to nearly 1400, but another commander, Colonel Thomas A. Smyth was named – sending Kelly back to regimental command. The Irish fought with Grant and Meade at The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. When Smyth was killed at Cold Harbor, Colonel Kelly was again asked to command the Irish Brigade. It would, again, not be for long.18

General Grant had, the previous year, taken the town of Vicksburg, Mississippi by siege. He would do the same for Petersburg, Virginia – but not before ordering an assault on the entrenched Confederate forces on June 16, 1864. Shortly before the battle, Kelly, at times “a grave man” spoke with foreboding. “I’ve lost my horse,” he said to Denis Burke (commander of the 88th New York Infantry), “and my black dog, and now they’ll have the little black man.” From the beginning of the war, Kelly had escaped every battle without harm.19

As always, the Irish Brigade found themselves in the thick of the fighting. Patrick Kelly ordered his men to charge the breastworks and led them onward. As they advanced, Kelly was shot “through the brow” and fell dead. After the battle, dispatchers recovered his body. Kelly’s troops “wept like children” at the loss of their commander.20

The funeral for Colonel Kelly was held at the house of his brother-in-law, Patrick Burke, in New York City on June 26. The event was crowded, and included a regiment of the New York National Guard, and “a large gathering of personal friends of Colonel Kelly….He died as he lived, brave and valiant to the last.” He was forty-two years old.21

Kelly was buried at Calvary Cemetery in New York City, beside his wife, who had died many years before him. Eventually, her two brothers, Michael and Patrick, were interred there as well.

The writing on his tombstone sums up his sacrifice: Killed while gallantly leading the Irish Brigade on the enemy’s works at Petersburg…Faithful to us here, we loved him to the last…mowed down by the pitiless scythe of Death, far from the green hills and loved home of his nativity…he no doubt regretted that his gushing life blood was not shed for Ireland.”22

One of the most visited memorials at Gettysburg is the Irish Brigade monument, located at the Stony Hill. In the Celtic cross, the New York regiments of the Irish Brigade are inscribed. At the base of the cross lies the Irish Wolfhound, symbolic of the devotion demonstrated by the men who fought in The Irish Brigade for the perpetuation of America. The people of Ireland today extol the ultimate sacrifices of men like Patrick Kelly and his Irish counterparts. They realize that the Irish immigrants helped win the victory for the Union that kept America and its Constitution alive. The example of the “ government of the people ” has been carried to many other nations of the world – including Ireland. While the victory cannot expunge or excuse the terrible losses, no doubt the stalwart Colonel Kelly would never have regretted the fight.23

The Irish Brigade monument

(author photo)

Sources: Baptismal Record: Patrick Kelly. Catholic Parish Registers of Ireland, Louth, Ireland, 1822, Ancestry.com. Kelly Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Patrick Kelly Gravesite, Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens, New York. Patrick Kelly Obituary, New York Daily Herald, 27 June, 1864. Murphy, T.L. Kelly’s Heroes: The Irish Brigade at Gettysburg . Gettysburg: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1997. Lincoln, Abraham. “The Gettysburg Address”, November 19, 1863. The New York Herald, 24 June, 1864. O’Dowd, Niall. Lincoln and the Irish . New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2018. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Scott, Colonel Robert N. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies . Series 1, Volume 27. Dayton, OH: Morningside Bookshop, 1993 (reprint). Tucker, Phillip Thomas. "God Help the Irish!" The History of the Irish Brigade. Abilene, TX: McWhitney Foundation Press, 2007. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Historic newspapers found at newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Patrick Kelly Family Tree, Ancestry. Kelly Baptismal Record, Catholic Parish Records, Louth, 1822.

2. Ibid.

3. Kelly Family Tree, Ancestry. No other information was available for Patrick’s mother or sister.

4. New York Daily Herald, 27 June, 1864. Elizabeth’s brothers are buried beside Patrick and his wife at the Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, Queens, NY.

5. Ibid.

6. O’Dowd, pp. 58-59. Murphy, p. 9. Tucker, p. 24.

7. New York Daily Herald, 27 June, 1864.

8. Murphy, p. 15.

9. Warner, p. 490. General Sumner, born in 1797, was the oldest general in the war at that time.

10. Tucker, p. 69.

11. New York Herald, 27 June, 1864.

12. Tucker, p. 70. O’Dowd, p. 62.

13. Tucker, pp. 93-95.

14. OR, vol. 27, part 1, p. 386, GNMP.

15. O’Dowd, p. 120. Murphy, p. 24.

16. Pfanz, p. 288.

17. New York Daily Herald, 27 June, 1864. Pfanz, p. 289.

18. Tucker, p. 14.

19. Murphy, p. 51.

20. Ibid.

21. The New York Daily Herald, 27 June, 1864. The New York Herald, 24 June, 1864.

22. Patrick Kelly Tombstone Inscription, Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens, NY.

23. Lincoln, The Gettysburg Address, Nov. 19, 1863.