Darkest April

by Diana Loski

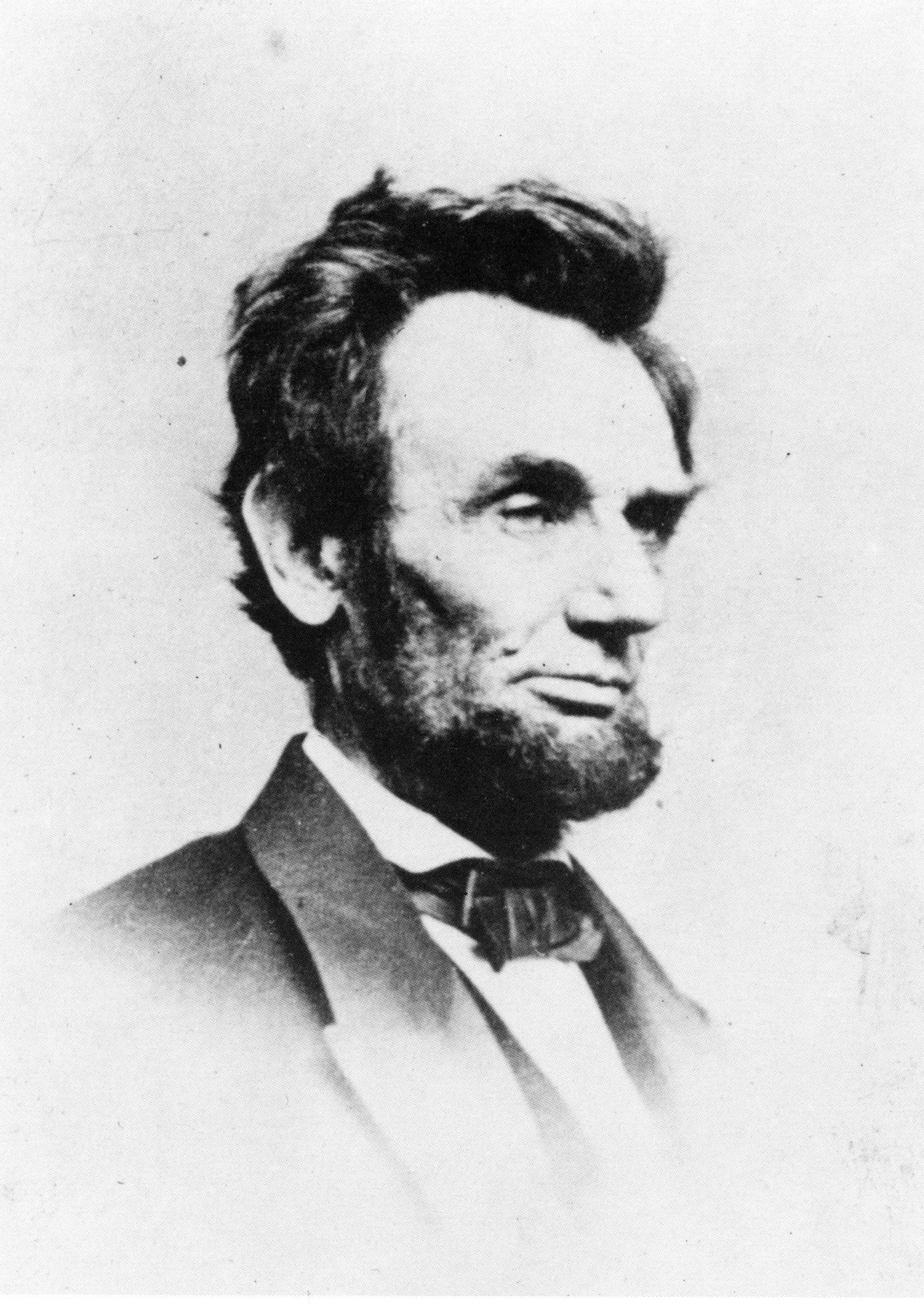

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

(Library of Congress)

Oh, memorable day! Oh, memorable night! Never before was joy so violently contrasted with sorrow!1

The United States has seen its unfortunate share of assassinations, yet never has the nation shown greater grief and mourning than over the first one: the shocking murder of its 16th President, Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln knew there were multiple threats on his life from the moment he was elected. He grew fatalistic about the threats, and he refused to let the possibility change his practices or habits. He had given an oath to protect the Constitution and the people, and he was determined to do it.

On March 14, 1865, just one month before his assassination, Lincoln was so worn with worry and exhaustion that on that day he had to conduct a Cabinet meeting in his bedchamber. With the fall of Petersburg, and then Richmond, at the beginning of April, Lincoln grew exuberant. He had no idea that, as the terrible war was coming to an end, so was his life.2

On Friday, April 14, elated with the knowledge that, with General Lee’s recent surrender at Appomattox Court House, the war was coming to a close, he and his wife, Mary, decided to celebrate by attending the theater, which had advertised the comedy Our American Cousin. Accompanied by friends Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone, the Lincolns arrived late and the play had already started. Sometime after 10 p.m. on that awful night, John Wilkes Booth, a narcissistic actor, gained entrance to the Presidential box. During a moment of hilarity on the stage, Booth fired a single shot into the back of Lincoln’s head. Lincoln immediately collapsed into unconsciousness – a comatose state from which he never awoke.

Several doctors, among them Charles Leale, the first one to reach the President in his box, and Charles Taft, who was lifted up into the box by members of the crowd, saw after a brief examination that the wound was mortal. Not wishing to have him die in a theater, they decided to move Lincoln to a house across the street. They took Lincoln to the Petersen House, which, in addition to housing the Petersen family, also had boarders. Placing the fallen President on a small bed of one of the boarders on the second floor, they placed him diagonally on the bed, removed the foot board, and then his clothing to see if there were other wounds. They then covered him with blankets. Gideon Welles remembered, “ His slow, full respiration lifted the clothes with each breath he took. His features were calm and striking.”3

Mary Lincoln entered the room with Clara Harris, her companion from Ford’s Theater. Robert Lincoln, too, came to the house. Mary collapsed into fits of agonized weeping, and was soon removed from the vigil. She then was allowed back into the chamber, and removed again when her grief overwhelmed her. Robert remained with his father through the night. Most of Lincoln’s Cabinet arrived, with other statesmen such as Senator Charles Sumner, upon whom Robert Lincoln sometimes leaned for support. One who was absent was William Henry Seward, who had been assaulted in his home that same night by an assassin and friend of Booth’s. Windows were opened due to a stifling closeness from the silent crowd. Outside, an equally somber mass stood in the mist and rain. That night, there was a late-rising moon that was obscured, due to the clouds.4

Lincoln gave his last breath, with a slight smile that formed on his lips, at 7:22 a.m. on Saturday, April 15, 1865. It was the day before Easter Sunday, a “bleak and cheerless April morning.” At Lincoln’s passing, the gathered group inside the house remained in stunned silence for several minutes. Then Secretary of War Edwin Stanton asked Dr. Phineas Gurley, a Presbyterian minister and friend of the President, to say a prayer. The men all knelt as the pastor prayed. Then, Stanton rose and said, with tears falling on his cheeks, “Now he belongs to the ages.”5

In the streets that surrounded Ford’s Theater and the Petersen House, there was an immense crowd of humanity to learn the fate of their President, “ men, women and children thronging the pavements and darkening the throughfares,” remembered journalist Noah Brooks. “It seemed as if everybody was in tears.” The group witnessed that morning “ a tragical procession ” as members of the military bore the President’s body to the White House. “Instantly, flags were…at half-mast, all over the city, the bells tolled solemnly, and with incredible swiftness Washington went into deep, universal mourning.”6

As the procession reached the White House, another large crowd waited. Despite the falling rain, “every head was uncovered, and the profound silence which prevailed was broken only by sobs and by measured tread of those who bore the martyred President back to the home which he so lately quitted full of life, hope, and cheer.”7

Mary Lincoln took to her bed, and remained there for many days, unable to attend the funeral. Friends and dignitaries came to the White House to offer condolences, but most of them she refused to see. Robert helped with funeral arrangements. Tad, the youngest of the Lincoln sons, was left to himself. On Easter morning, he asked one of the staff if his father had gone to heaven. When the attendant assured Tad in the affirmative, he replied, “Then I am glad he has gone there, for he was never happy here. This was not a good place for him.” All through the day, workers sawed and hammered, making a bier for the casket. The noise haunted Mary Lincoln. Her deep grief and insomnia had made her physically ill, and she begged them to cease that particular labor.8

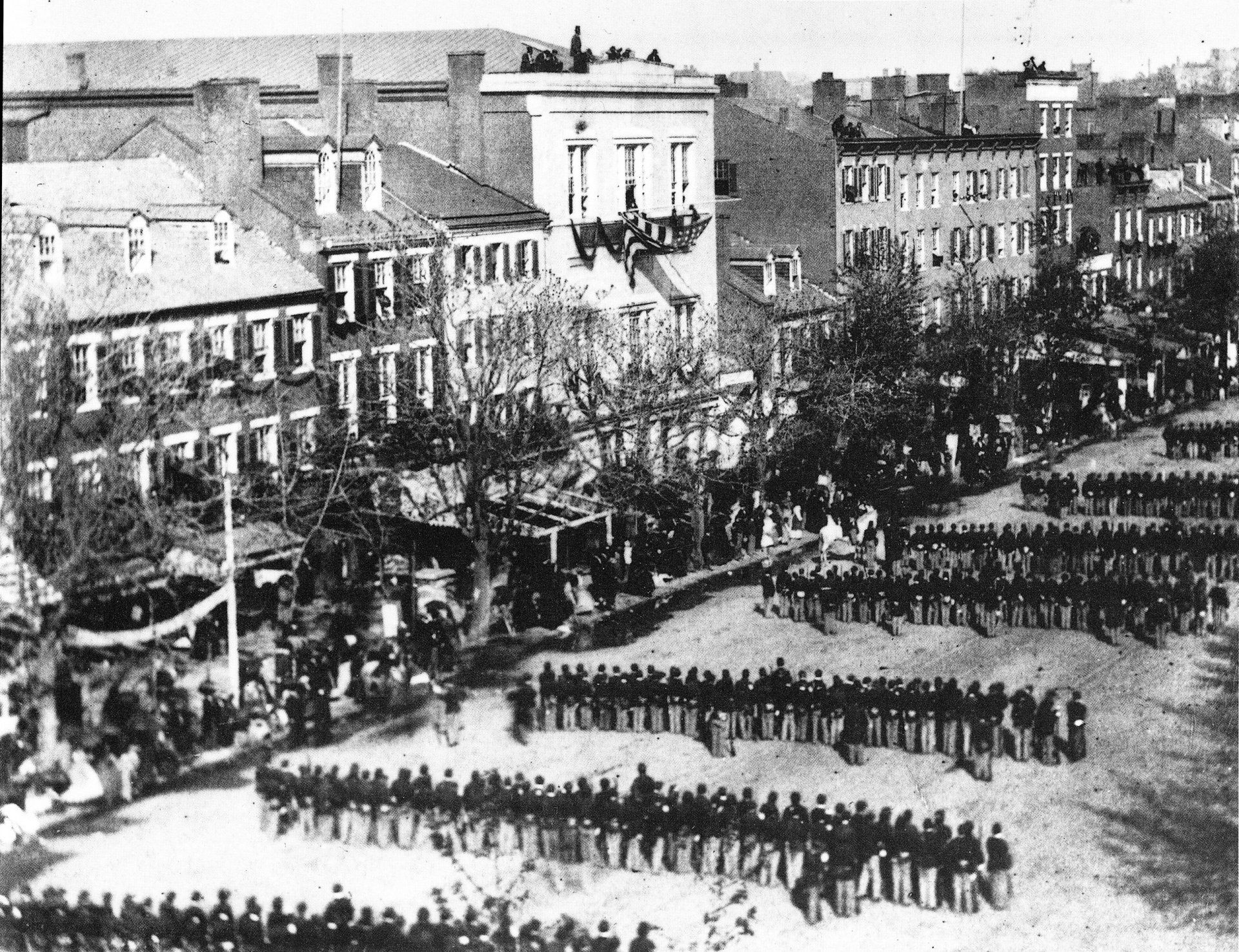

Ford's Theater

(Library of Congress)

End Notes:

1. Keckley, p. 81. Elizabeth Keckley was a former slave and seamstress, who was also a friend to Mary Lincoln.

2. Oates, p. 417.

3. Steers, p. 127.

4. Brooks, p. 230.

5. Kunhardt, p. 124. Sandburg, p. 716. Steers, p. 124.

6. Brooks, p. 231.

7. Ibid.

8. Phillips, p. 277. Baker, pp. 247-248. Mary Lincoln remained closed up in the White House until May 22, nearly six weeks after her husband was assassinated.

9. Sandburg, p. 730. Kunhardt, p. 125.

10. Kunhardt, pp. 130-131.

11. Brooks, p. 236.

12. Sandburg, p. 730. Kunhardt, p. 140.

13. Kunhardt, p. 140. Brooks, p. 235. Sandburg, p. 730.

14. Steers, p. 127. Kuhnhardt, p. 133.

15. Good, p. 196.

16. Lincoln, p. 709.

17. Goodwin, p. 748.