Elizabeth Thorn: "Those Were Hard Days"

by Diana Loski

At Evergreen Cemetery, the Gettysburg Women’s Memorial depicts a woman, wiping her brow as she prepares to bury scores of the Gettysburg slain. The woman memorialized by the statue is Elizabeth Thorn, who was expecting her fourth child in the summer of 1863. Her husband, the keeper of the cemetery gatehouse, had been called away to fight for the Union, leaving her with the work at the cemetery. Her delicate appearance belied her courage and fortitude. She would no doubt have enjoyed an ordinary, anonymous life, but the Battle of Gettysburg changed that.

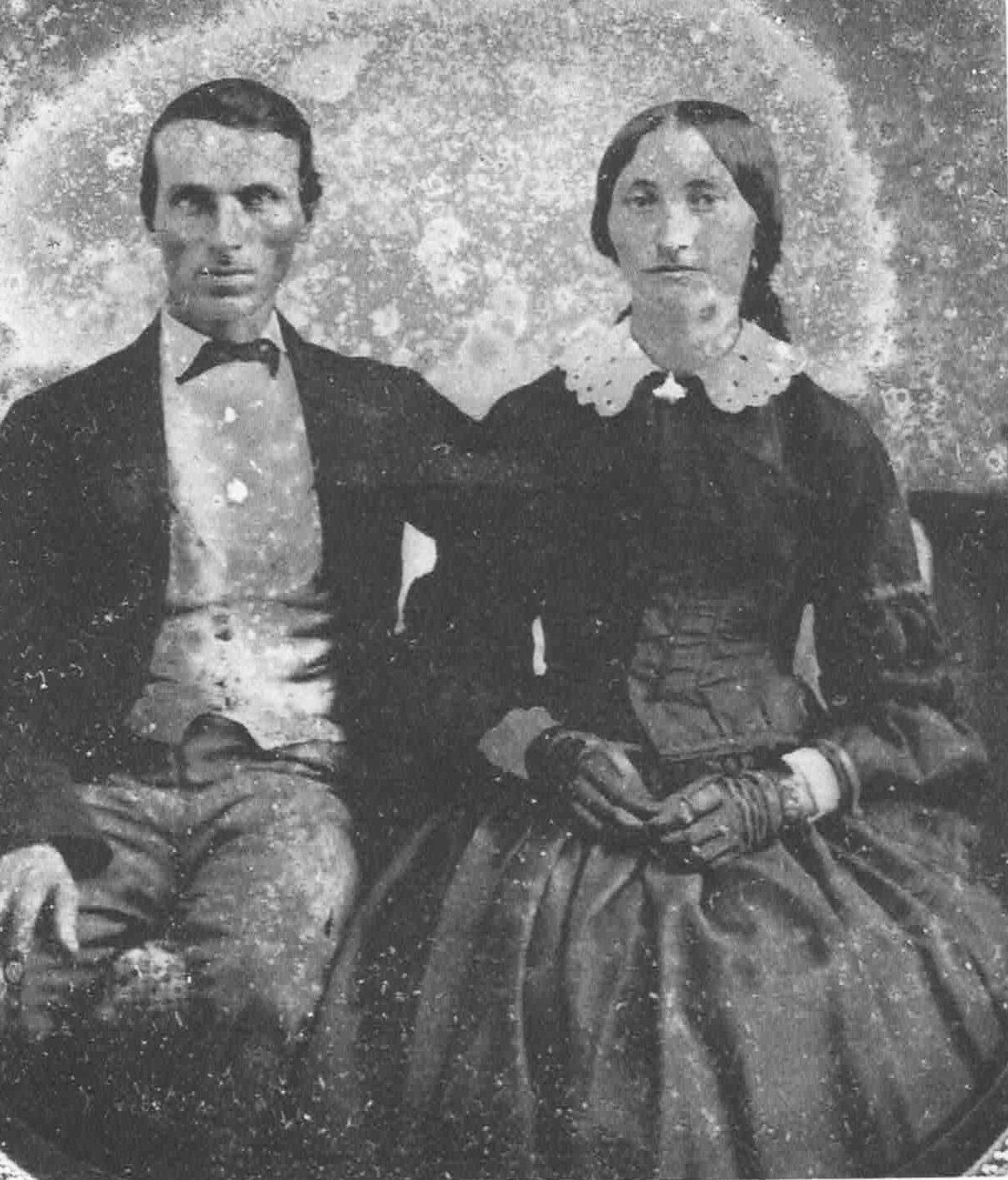

Elizabeth Masser Thorn was born in Eicheldorf, Germany, on December 28, 1832. She was a pretty child with dark hair and fine features. By age 21, she had fallen in love with a boy from her hometown, but their hopes to marry were dashed when her parents, John and Catherine Masser, decided to emigrate to the United States. During the long and arduous voyage, someone stole the Massers’ belongings. They arrived at Ellis Island with only the clothes on their backs. Another passenger, Peter Thorn, aided them and helped them to continue their journey to Pennsylvania – as he was also going there. A friendship blossomed between Peter and Elizabeth, and they were married on September 1, 1855.1

A few months later, on February 9, 1856, Peter accepted employment as the caretaker of a new cemetery that was being built in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The cornerstone for the Cemetery Gatehouse was laid on the same day Peter accepted his job. The family called the edifice home for many years.2

Elizabeth’s parents, who could not speak English, moved in with their daughter and son-in-law. Elizabeth and Peter lived with their children in three rooms on the northern section of the gatehouse, paying no rent. Her parents occupied the other side, on the southern portion, divided from their daughter by the archway. It was a definite benefit for the family in the uncertain years before the war.3

Soon after Peter accepted his new position, as the Thorns prepared to move to their new home in Gettysburg, Elizabeth was surprised to hear a knock on the door. Opening it, she saw her beloved former suitor. He had raised money to find her in America. He begged her to leave with him. Elizabeth almost acquiesced, but the cry of her newborn son stopped her. Her jilted lover departed, never to return.4

When war erupted in the spring of 1861, Peter Thorn did not immediately enlist. Like many fathers with paying jobs, he felt the war would be of short duration. When a year passed with escalation of the conflict, Peter joined the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry in August 1862. Elizabeth, now the mother of three small sons, Frederick, George, and John, promised to stay on as caretaker of the cemetery in her husband’s absence.5

During the last days of June in the summer of 1863, repeated alarms of a Confederate invasion finally proved true. On Friday, June 26, Elizabeth, expectant with the couple’s fourth child, was busy with her interment duties, with her aged father as her only assistant. She was alarmed to see hordes of men in gray and butternut uniforms riding unchecked through town to where she lived on Cemetery Hill, shooting, shouting, and looking for food. “They fired off their revolvers to scare people

,” she recalled. “They chased people out….and jumped over fences. When they rode into the Cemetery I was scared….I fainted from fright.” The invaders took pity on the frail looking mother-to-be. “They said we should not be afraid of them, they were not going to hurt us.”6

When the clearly malnourished soldiers strode to the Gatehouse and asked for food, Catherine, Elizabeth’s mother, quickly obliged. As the men sat near the cemetery enjoying their meal, another Confederate rode up to them, holding the reins of a riderless horse.7

When his friends asked him where he found the horse, the soldier explained to his comrades that he had killed the owner, a Union soldier. “Yes, the ____ ____ shot at me,” he explained, “but he did not hit me, and I shot at him and blowed

[sic] him down like nothing, and here I got his horse and he lays down the pike.” Elizabeth later learned that the slain soldier was George Sandoe, a Gettysburg man who had recently enlisted in the militia. He was the first Union soldier to be killed at Gettysburg. There would be thousands more to follow.8

The Confederate invaders left Gettysburg the following day for York. If Elizabeth had hoped for a peaceful respite, she was sorely disappointed. On Wednesday, July 1, she noticed from her upstairs window that, “Union soldiers came in all directions.” Busy with her work at the cemetery and tending her three small sons, Elizabeth returned to the window at intervals during the day. She noticed in the afternoon that the Confederate forces pushed the men in blue through town, toward Cemetery Hill – and her home. She also noticed artillery and a small Union force already on the hill opposite the Gatehouse.9

She answered a knock that afternoon and welcomed a Union soldier, a member of General Howard’s staff, inside. He requested a man to help acquaint them with the area, as they planned to hold the high ground there.

Elizabeth’s father, who was the only man in the area not in uniform, spoke no English. Elizabeth offered to go instead, and helped to orient the officer with the land and the roads. As they walked through fields of flax, oats and then wheat, they came upon some Union soldiers who were concerned by her presence. “They all held against me coming through the field, but as he said I was all right, and it did not matter, why they gave three cheers and the band played a little piece.” She identified the York, Harrisburg, and Hunterstown Roads for the staff, and was then escorted home.10

The Gatehouse, Evergreen Cemetery

(author photo)

A few hours later, three generals appeared at her door, requesting a meal. They were corps commanders of the Army of the Potomac: Generals Sickles, Howard and Slocum. As the Confederates had already cleaned out her pantry, the meal for the three Union commanders was a humble one.

As the generals conversed, Elizabeth’s three sons watched them and were especially interested in General Howard’s gestures. The commander of the Union Eleventh Corps had lost his arm in the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier. As he talked, with a great deal of animation, his empty sleeve flapped in the air, enthralling the Thorn boys.11

As the Union generals prepared to leave, Howard warned Elizabeth that there would be hard fighting the next day. He urged her at first to keep to the cellar. Then, changing his mind, he told her to “leave this house and get as far away in ten minutes as possible. Take nothing but the children and go.”12

Elizabeth and her parents obliged, hurrying down the Baltimore Pike with the three boys. They stopped at a home for the night, and tried to find a place to sleep among the throng of Union soldiers. Realizing that she had eaten nothing that day, the pregnant Elizabeth felt unwell. At midnight, July 2, she and her father decided that they would make the trek back to the Gatehouse for supplies and any food that they had left.

Stepping over the rows of prostrated soldiers on the floor, she noticed one as he rose to a sitting position and beckoned to her. “He took a picture out of his pocket and on it was [sic] three little boys, and he said they were his, and they were just little boys like mine, and would I please let him have my little boys sleep near him, and could he have the little one close to him.” Elizabeth placed her sons near the homesick soldier, and left to salvage what she could from her home on Cemetery Hill.13

The Union army had already taken over the house. “We could not get near the house for the wounded and the dead,” she later explained. “My father went to the pigpen and said, ‘the pigs are gone.’” When they did manage to get access to the cellar, she saw that it was filled with Union wounded and dying, miserable in their suffering, calling for their wives and children. Elizabeth managed to find her mother’s shawl, which was the only thing she took with her. She and her father returned to the farmhouse where her mother and sons were sleeping. Elizabeth plucked the youngest from the sleeping soldier, and the family walked farther south on the Baltimore Pike to the Henry Beitler farm. There they were able to eat for the first time in over twenty-four hours.14

Elizabeth and her family remained at the farm through July 3. On that day, the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg, she learned about the death of a young civilian named Jennie Wade, whom she knew.15

On Tuesday, July 7, Elizabeth finally made the journey back to their home on Cemetery Hill. The sight that greeted her was a desolate one. The home was gutted and the furniture had been taken – although the latter did not surprise her. While at the Beitler residence, she noticed that “some of our furniture was going on some of our [Union] wagons down the pike, and my boys wanted me to go out and stop it.” She was unable to retrieve the family belongings. In addition to the emptiness of the rooms, windows were shattered, and any bedding or mattresses left behind were covered with blood and dirt. The water pump was broken and the stench of death pervaded the air. Elizabeth had the pump fixed, then spent four days washing what was left of the family’s beds and floor.16

She had scarcely finished when another, greater, task befell her. David McConaughy, the President of the Evergreen Cemetery Association, told her to dig graves for the many dead soldiers. In the intense July heat, the numberless corpses were quickly decomposing, turning black in the sun. Many were expanding and then bursting in the humid weather. Two soldiers had remained behind to aid in the task, but the terrible stench sickened them, and they left after two days. With only her father to help, Elizabeth buried ninety-one soldiers and several civilians (who had died in the interim) on Cemetery Hill. The thirty-year-old expectant mother worked intensely, without complaining. Each was someone’s son, or someone’s husband. She thought of that as she dug, hauled and interred the remains, some of which were beyond description.17

Of the ninety-one soldiers buried by Elizabeth, sixty-six remain in the Evergreen Cemetery. She wore the same dress for six weeks – evidence that she ignored her own needs as she continued with her exhaustive and macabre work.18

Three months after the battle, Elizabeth gave birth to a baby girl. She named the baby Rose Meade, in honor of Union army commander George Meade. Elizabeth remembered that Rose was “a dear little baby. But it was not very strong, and from that time on my health failed and I was a sickly woman.” The child, never of robust health, died at age fourteen.19

Peter Thorn survived the war and returned to Gettysburg in 1865, resuming his duties as caretaker of the Evergreen Cemetery. Five more children were born to the couple: Peter, Lillian, Ezra, Louisa, and Emory. In 1874, Peter resigned from his position and purchased a nearby farm. Among the family’s possessions was a clock, the only item that was not taken or destroyed by the Battle of Gettysburg.20

Elizabeth’s parents continued to live with them for the duration of their lives. John Masser died in July 1869, and Catherine Masser followed him in 1890. Both are buried in the cemetery near the Gatehouse. Peter Thorn died in January 1907, at age 82. Elizabeth followed him several months later, at age 74. Both are buried in Evergreen Cemetery, within sight of the Gatehouse, the place they had once called home.21

In 2002, the Women’s Memorial, created by sculptor Ron Tunison, was dedicated at Gettysburg to honor and remember the many women who served during America’s terrible fratricidal conflict. Placed south of the Gatehouse in Evergreen Cemetery, the monument depicts the expectant Elizabeth Thorn, a fitting example for all.22

Born on the other side of the world, Elizabeth Thorn is a perfect example of the American citizen. She will always be remembered for what she accomplished, what she endured, and what she gave at great cost to honor the fallen at Gettysburg. Among the Union slain she also buried Confederate dead – they were all someone’s son to her. She simply recalled, “ Those were hard days.”

23

War always exacts the highest of prices. Its vestiges are still visible on Gettysburg’s Cemetery Hill, where some of the combatants were placed by a young mother who cared for them when no one else could bear it – and who, eventually, found eternal rest in their midst.

The Gettysburg Women's Memorial

(author photo)

Sources: “A Woman’s Thrilling Experience of the Battle”, The Gettysburg Compiler, 7 July, 1905. Elizabeth Thorn Obituary, The Gettysburg Compiler, 18 October, 1907. The Elizabeth Thorn File, Civilian Accounts, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Kennell, Brian A. Beyond the Gatehouse: Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery . Gettysburg: Evergreen Cemetery Association, 2000. Peter Thorn Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Peter Thorn Obituary, fragment, Thorn File, ACHS. The Gettysburg Women’s Memorial File, Gettysburg National Military Park. Information on John and Catherine Masser’s death dates are found on their graves in Evergreen Cemetery, Gettysburg.

End Notes:

1. Elizabeth Thorn File, p. 1, ACHS.

2. Peter Thorn Obituary, ACHS.

3. Ibid.

4. Elizabeth Thorn File, p. 1, ACHS.

5. Peter Thorn Obituary, ACHS. Peter Thorn

Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

6. The Gettysburg Compiler, 7 July, 1905.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Elizabeth Thorn Account, p. 3, ACHS.

10. Kennell, p. 30.

11. The Gettysburg Compiler, 7 July, 1907.

12. Thorn Account, p. 4. ACHS.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., p. 6.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid. p. 7. Elizabeth never identified the Beitler farm. It is the extrapolation of historians that the farm was the likely place where she went.

17. Kennell, p. 33.

18. Thorn File, p. 7, ACHS.

19. Ibid., p. 8.

20. Peter Thorn Obituary, ACHS.

21. John and Catherine Masser graves, Evergreen Cemetery. Peter Thorn Obituary, ACHS. Elizabeth Thorn Obituary, The Gettysburg Compiler, 18 Oct. 1907.

22. Gettysburg Women’s Memorial File, GNMP.

23. Elizabeth Thorn File, p. 3, ACHS.