During the Civil War, the almost innumerable infantries supplied the main body of the fighting armies. The artillery was the new weapon of the age then, much like the tank during World War I.

At Gettysburg the big guns served a significant purpose during those three summer days in 1863 – and provided the necessary aid to propel the Union to victory.

During the pivotal battle, the heroics of the infantries of both sides usually garner the accolades of history. There were, however, brave men – many of whom perished on the field or languished in makeshift hospitals during the four years of conflict – who manned the big guns rather than carry a musket, although they would have done whatever was asked of them to save the nation.

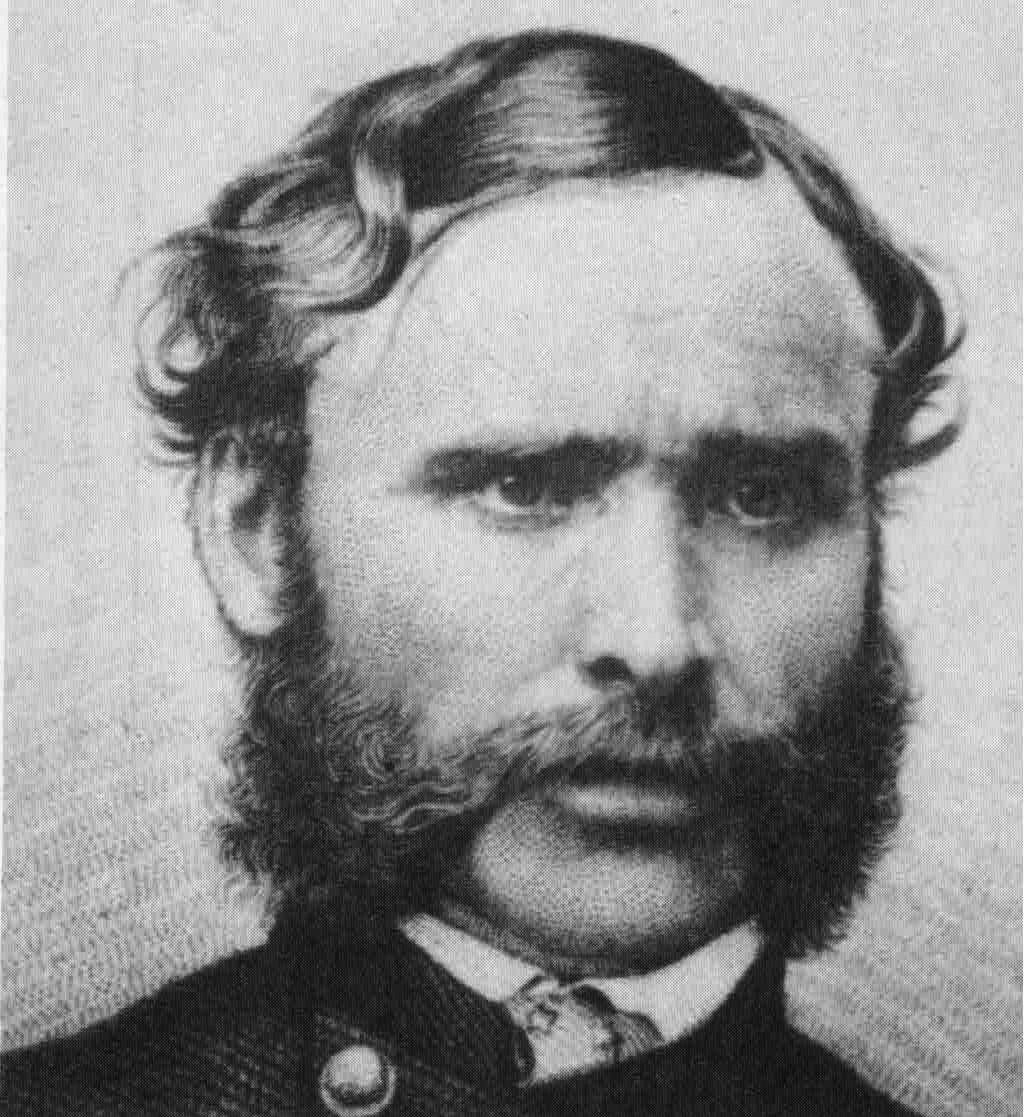

One of them was a man named Freeman McGilvery.

Freeman McGilvery, the progeny of Scot-Irish immigrants, was born on October 27, 1823 to Robert and Elizabeth Chase McGilvery in the hamlet of Prospect, Maine. Growing up in the Down East area south of Bar Harbor, it was only natural that he would be drawn to a life at sea. He left home at age eleven as a sailor “ to earn a livelihood for himself and his indigent friends

”. Trained early in hard work and industry, McGilvery was soon self-reliant. Before the war, he had amassed a significant fortune as a “ master mariner

”. After working at sea and traveling to places from Brazil to Hawaii, he engaged in the mercantile business. When it failed, he again took to the sea. By the time the clouds of war amassed, McGilvery had married and was considered “master of one of the finest ships of the Old Bay State” of Massachusetts. He was in Rio de Janeiro when he learned of the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter. He immediately set out for home, and arrived months after the war had begun.1

It seems odd that McGilvery offered his services to the artillery branch of the Union army rather than the Navy. He began the war with the rank of captain, and recruited enough men to form the 6th Maine Battery in early 1862. Their first battle was at Cedar Mountain in August 1862, where McGilvery and his men helped to secure the Union left flank. McGilvery also fought at the Battle of Antietam, supporting the Union Twelfth Corps against some of Hood’s men who were firing on General Mansfield’s troops from the East Woods. One of their bushwacking bullets hit Mansfield, killing him.2

McGilvery was also engaged at the Battle of Fredericksburg, and was with the army during the long winter. On February 5, 1863, McGilvery was promoted to the rank of major, and given command of the 1st Volunteer Brigade of the new Artillery Reserve. These veteran troops were available to go to whichever unit needed them in battle. McGilvery commanded his new brigade at Chancellorsville in the early spring of that year.3

When General Lee began his invasion of the North, McGilvery and his men traveled with the Army of the Potomac in pursuit. On June 23, McGilvery was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The batteries he would lead at Gettysburg were the Massachusetts Light (5th) Battery, led by Captain Charles Phillips, the New York Light (15th) Battery, commanded by Captain Patrick Hart, Captain James Thompson’s Pennsylvania Batteries C and F, and their newest addition – the Ninth Massachusetts Battery, led by Captain John Bigelow.4

At Gettysburg, the Union batteries, usually comprised of six guns each, contained more cannon than the Confederate batteries, which contained four. Ideally, 150 men manned each of these batteries, but like the diminishing of infantry numbers, with battles the number of those operating artillery had lessened by 1863. At Gettysburg, the entire Artillery Reserve, commanded by Brigadier General Robert O. Tyler, consisted of 114 cannon – which made up 21 batteries.5

By June 27, the artillery reserve reached Frederick, Maryland. Three days later, they camped near Meade’s headquarters in Taneytown. The next day, July 1, they awoke to clouds and significant humidity. News of battle soon reached them. At sunset, McGilvery received orders to move. Two of his batteries immediately began the trek toward Gettysburg. By dawn the following day, July 2, the entire Artillery Reserve trod the Taneytown Road to Pennsylvania. By mid-morning most of them deployed near Cemetery Ridge, awaiting orders.

Because Gettysburg had not been chosen by either Lee or Meade as the place to fight, during the morning of July 2 a significant portion of the Confederate army had not arrived. The morning, then, was not a time of battle, but of positioning. It would change because of the actions of one recalcitrant and restive general.

General Dan Sickles, commander of the Federal Third Corps, was dissatisfied with his position. Although personally brave, he was a politician by profession and used to having his own way. He did not care for George Meade, the new Union commander, and felt that Meade’s cautious personality would not bring a Union victory at Gettysburg. Sickles decided to move his men out toward the Emmitsburg Road, in direct disobedience to orders.

In the morning, Lee had been told by a scout on his staff that there were no soldiers on Little Round Top or in any of the fields below it. He gave an order to General Longstreet, Lee’s second in command, to attack up the Emmitsburg Road and flank the Union line. As Longstreet’s men marched toward their position on Warfield Ridge, they saw men in blue where Lee had said they would not be – in the Wheatfield and Peach Orchard. At about the same time, George Meade learned that Sickles had moved his corps of about 10,000 men away from the Union line, with notable gaps between them.

General Meade would have commanded Sickles to return to his original line with the rest of the army, but Longstreet began his attack. To retreat at that time would have been like conceding the battle to the Confederates. Meade’s only choice was to reinforce Sickles’s line.

McGilvery saw a courier ride up to his men, and heard the soldier call for him by name. “Captain Randolph, chief of artillery of the 3

rd

Corps, sends his compliments and wishes you to send him two batteries”. Colonel McGilvery turned to Captains John Bigelow and Patrick Hart and sent them into the fray. The two batteries hurried toward the Peach Orchard, with McGilvery leading them. They set up their line around the Abraham Trostle Farm under a barrage of cannon fire from Porter Alexander’s Confederate artillery, which was stationed along the Emmitsburg Road.6

As infantry and artillery units poured into the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield, “pandemonium reigned”. Men fell like grain before the scythe, the skies grew black with smoke, and the noise grew so intense that orders could not be heard. With each artillery blast, horses were cut in two as well as the men around them. A fragment of exploded shell disemboweled one of the horses hitched to a limber, and the terrified animal bolted, carrying away the rest of the team and the limber chest before falling down dead. The frenzied moment sent some of the cannoneers on the chase to rescue the surviving horses and the much-needed ammunition. In Bigelow’s Battery alone, 80 of the 88 horses were killed in the battle.7

Through it all, McGilvery remained calm. As the Union line on Cemetery Ridge unraveled, Union troops from Culp’s Hill were pulled from their position and were rushing to hold the Union center line. To gain time for this new deployment, McGilvery knew his men had to hold under extreme conditions – and that many of them would be sacrificed. He told his men to remain and operate the artillery “at all hazards”, even if it resulted in the sacrifice of their batteries “if need be”. For many, that sacrifice was made. Bigelow’s Battery alone lost four of their six guns. Before losing them, the men drove spikes through the barrels.8

It is impossible to accurately quantify the death and destruction of the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield at Gettysburg. As more infantry troops arrived, the fight became a progressive one, known as the en echelon

attack. Several general officers were killed, wounded or captured in the few hours of terrible conflict. Among the killed were General William Barksdale of Mississippi, who fell near the Trostle farm, and Colonel George Willard, a brigade commander who was killed by a shell that exploded on his head, decapitating him. Among the wounded were Union Generals Sickles, Barnes, and Graham.9

As the Confederates pressed their advantage in the Peach Orchard, McGilvery’s guns were in danger of capture. The men began to retreat back to Cemetery Ridge, pulling the guns by prolonge

– where men personally pull the guns back using rope, loading and firing as they retreated. The French word for “prolong” was just that – even in retreat, the men continued to fire their weaponry. So many of the horses lay mutilated on the field that prolonge

became a necessity. Once back on Cemetery Ridge, McGilvery used his artillery brigade to fire upon advancing Confederate forces, namely Wilcox’s and Wright’s infantry brigades. McGilvery's actions aided the infantry in turning back the enemy troops.

The entire Union line was chaotic on July 2 because of Sickles’s errant move. While stalwart Union soldiers by the thousands rushed to the aid of the Third Corps, the artillery had helped to save the day. It was Freeman McGilvery’s master stroke of the battle, and his finest hour of the war.

The following day, July 3, McGilvery’s artillery brigade remained on Cemetery Ridge, not far from where the Pennsylvania Memorial stands. He and his men helped to stem the Confederate tide during Pickett’s Charge. The battle ended, and on July 4 Confederates retreated.

McGilvery managed to survive Gettysburg, though he had lost some choice men from his artillery brigade. The official number of men lost under McGilvery’s command at Gettysburg included 17 killed, 71 wounded and five missing, a total of 93 casualties. It comprised a significant percentage of men engaged, especially for an artillery brigade.10

In September 1863 McGilvery was promoted to a full colonelcy for his gallantry at Gettysburg. He was engaged in the spring of 1864 in Grant’s Overland Campaign, including the Battles at The Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor. Because of the heavy losses in those battles, McGilvery’s commander General Robert O. Tyler was promoted to lead a brigade in John Gibbon’s Infantry Division. McGilvery replaced Tyler as commander of the Union Artillery Reserve, which he led during the battle, then siege, of Petersburg. In August, McGilvery was named Chief of Artillery of the Federal Tenth Corps.11

General Lee’s lines at Petersburg were perilously thin. In order to lure away Union troops, Lee dispatched the irascible Jubal Early to play havoc with the areas around Washington, and invade the Federal capital if possible. On July 9, Early attacked Union troops at Monocacy near Frederick, Maryland – and won a much-needed Confederate victory. He then rode toward Washington. He was, after terrifying the people in the capital, turned back just miles from the city. He then rode north and burned the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania on July 30.

To render aid to the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg, the Federal Tenth Corps, a serving from the Army of the James, arrived in northern Virginia. Colonel McGilvery received a promotion and was transferred to their corps. He was named their Chief of Artillery.12

As Jubal Early had achieved some success with luring away Federal troops, it did not bode well politically for Abraham Lincoln, who was up for reelection in a few months. Grant decided upon a similar tactic. The Tenth Corps engaged Confederate troops at Deep Bottom, Virginia, a wilderness area on the James River. General David Birney, the commander of the Tenth Corps and a veteran of Gettysburg, initiated the attack. For three days, beginning on August 18, the two sides clashed in grueling heat. Early in the fight, McGilvery was shot in the finger. He refused to leave his post, as he “had the command of a hundred guns”. The Confederates again claimed victory after the Union troops retreated toward Petersburg, but the Federal objective had been achieved. They had hoped to weaken the Confederate line by taking more Southern lives, and the detritus of the battlefield showed a significant Southern loss.13

As August turned to September, McGilvery's finger became infected. The army surgeon deemed that amputation was necessary. McGilvery “rode the length of his line” at Petersburg “and in the best of spirits threw himself upon his bed for a slight amputation”. Due to the increased infection, the surgeon suggested chloroform, and McGilvery acquiesced.14

The amputation occurred in the morning of September 2. “Chloroform was administered, and after a little incoherent talking, the Colonel dropped into a deep sleep,” wrote his second in command to Mrs. McGilvery.15

He suddenly stopped breathing due to the effects of too much chloroform.

In spite of all attempts to revive him, including artificial respiration and “all the usual restoratives”, Freeman McGilvery died at the age of forty. He was taken back to his native Maine and buried in the village cemetery at Searsport.16

Because his marriage had begun at the onset of war, and he died during that war, Freeman and Hannah McGilvery had no children. His widow remarried and little has been remembered of his valiant man.

“I cannot think of business while traitors are in arms, and the liberty of our country is in danger,” McGilvery said to his wife when she had hoped he would remain at home. He sealed his devotion to the Union with his life.17

“His energetic and untiring military zeal inspired us all,” remembered his assistant adjutant, O.S. Dewey. “We had all learned to love him.”18

Sources: 9 th Massachusetts Accounts File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). 9th Massachusetts Memorial, Trostle Farm, GNMP. Baker, Levi W. History of the Ninth Massachusetts Battery. First published in 1888. Excerpts, 9th Massachusetts File, GNMP. Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography . Vol. IV, 1887-1889, Excerpts at Ancestry.com. Letter, O.S. Dewey to Hannah McGilvery, 3 September, 1864, Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 September, 1864. Obituary of Freeman McGilvery, Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 September, 1864. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam . Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Additional information provided by McGilvery’s Artillery Brigade Marker, Hancock Avenue at Gettysburg and Petersburg National Battlefield.

End Notes:

1. Drake, p. 140. Obituary, Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 Sep., 1864.

2. Drake, p. 140, Sears, p. 206. The 6 th Maine Battery (Dow’s Battery in 1863) was engaged at Gettysburg.

3. Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 Sep, 1864. Drake, p. 141.

4. Pfanz, p. 455.

5. Ibid. Not all of McGilvery’s batteries contained six guns. Hart’s Batteryhad four Napoleons at Gettysburg. A good estimate of men at each battery at Gettysburg was likely about one hundred, making about 500 in McGilvery’s artillery brigade.

6. Baker, p. 56, 9 th Mass File, GNMP. Pfanz, p. 307.

7. Drake, p. 141. Pfanz, pp. 315-316. 9 th Mass. Battery Memorial, GNMP.

8. Baker, p. 60, 9 th Mass File, GNMP. McGilvery’s words explain the dire circumstances of the battle.

9. General Semmes, CSA, was also mortally wounded in the battle, but it is likely his wound came in the environs of the Wheatfield. His military records are sparse, and it is impossible to know for certain.

10. McGilvery’s Artillery Brigade Marker, Hancock Avenue, Gettysburg.

11. Drake, p. 140. Warner, p. 516.

12. Drake, p. 140.

13. Petersburg National Battlefield. Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 Sep., 1864.

14. Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 Sep, 1864.

15. Letter, OS Dewey to Hannah McGilvery, 3 Sep, 1864.

16. Ibid.

17. Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, 21 Sep, 1864.

18. Letter, OS Dewey to Hannah McGilvery, 3 Sep, 1864.

Artillery at Gettysburg

The artillery in 1863 proved much more accurate than their predecessors from earlier wars. There were several types of cannon used in the battle by both the Union and the Confederacy. Most of them were either the rifled artillery, most of them being Parrott guns and 3-inch rifles, or the smoothbore bronze models, now appearing with a green patina on the field of battle, most them being Napoleons.

There are other types on the field, such as howitzers (a much older type of artillery. Some specimens are visible on West Confederate Avenue behind the Virginia Memorial), and Whitworth rifled cannon (with a range of up to five miles – two are found on Oak Hill west of town).

The Parrott guns and 3-inch rifled cannon, painted black, show early rifling (grooves within the gun). The rifling created a spin on the projectile, making the deadly missiles more accurate. The artillery atop Little Round Top, for example, could easily fire upon the troops charging toward the Union line during Pickett’s Charge, up to two miles away.

The Napoleons (named for Napoleon III), being smooth within, had a range of accuracy for about one mile – which is still impressive.

The artillery for both sides of the battle used limbers (single chests on wheels) or caissons (double chests). Weaponry included explosive shells, solid shot (bolts or cannon balls) that were eponymously solid (the hole on Gettysburg’s Trostle Farm shows solid shot damage), and canister (smaller iron balls that were packed in a can, separated within by sawdust). When canister was fired at close range, the heat from the blast melted the can. The iron balls flew out like a giant shotgun, decimating advancing infantry. On the monument for Cowan’s Battery, near the High Water Mark Memorial on Cemetery Ridge, is the terse quote: “ Double canister at ten yards.”

The artillery did significant damage to troops during the battle. It is one of the reasons why some troops remain missing in action. True, some of the missing included the captured or deserters. But many are missing because of the devastation to the human body caused by artillery. After an artillery barrage, sometimes there were no bodies left to find.