The climactic and disastrous Pickett’s Charge, the most famous part of the battle at Gettysburg, most often recalls Pickett’s Division as they crossed the undulating, mile-wide field toward the unattainable Union center. What is less known is that there were two additional divisions along with Pickett’s troops who made that fateful charge at Gettysburg. They had fought bravely, too, on the opening day of the battle, losing many in the struggle, while Pickett’s men had arrived late the following day. These two less known divisions fought significantly more than most others involved in the battle, engaged during two of the three days at Gettysburg.

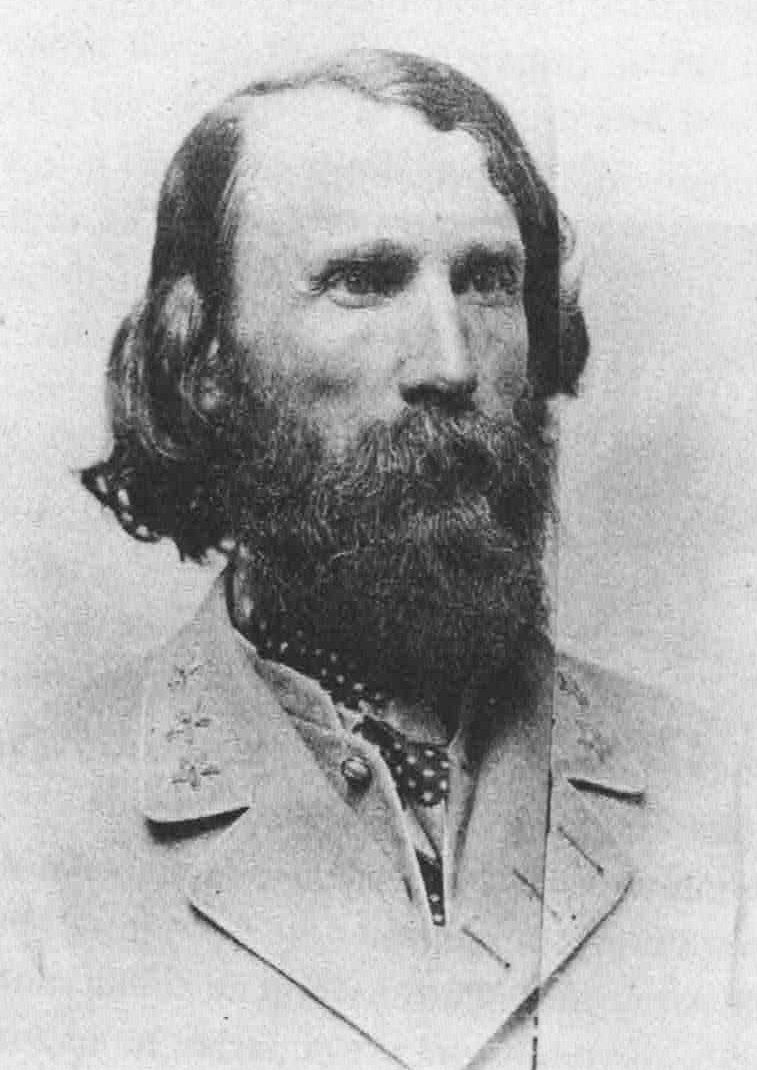

Their leader was the most unusual of Lee’s lieutenants, and he is rarely mentioned at Gettysburg, for good reason. His name was A.P. Hill.

Ambrose Powell Hill, nicknamed “Little Powell” was born in Culpeper, Virginia, on November 9, 1825, the youngest of five children. His father, Major Thomas Powell, was a successful statesman and merchant. His mother, the former Frances Russell Baptist, was ardently religious. Young Powell, named for an uncle and grandfather, turned out a bit more worldly than his mother wished.1

Powell received his coveted appointment to West Point at the age of 18, slated to graduate with the class of 1846. The red-headed Powell had a temperament to match, yet he was popular with his classmates and the ladies. While heading home for summer from West Point in 1844, he stopped for a visit to nearby New York City. During his short time there, he visited a brothel, and contracted venereal disease. The youthful indiscretion had a major impact on the young cadet for the rest of his life.2

Ill for several months with gonorrhea, Hill was unable to graduate with his class, and instead finished with the class of 1847. Placed in service with the U.S. Artillery, Hill saw action at the end of the Mexican War. He then was sent, like many, to Florida to fight the Seminole uprisings until his poor health required him to take a less strenuous task. He finished the antebellum years working for the U.S. Coastal survey, with headquarters in Washington, D.C.3

While serving in this capacity, Hill became engaged to a young woman named Ellen Marcy, the daughter of a highly esteemed major of the Federal army. Her parents learned of their prospective son-in-law’s disease and strongly discouraged their daughter from the marriage. She instead married future Union general George McClellan. A.P. Hill apparently held no rancor toward McClellan or Ellen Marcy for the rejection. He soon found solace with another, Kentucky belle Katherine (Kitty) Morgan, the sister of future Confederate cavalry commander John Hunt Morgan. The couple wed in 1859. Soon after his wedding, Hill was a groomsman at George McClellan’s marriage.4

War came soon after both weddings, and A.P. Hill left his expectant wife in Culpeper, enlisting his services for the Confederacy in March 1861. He began the war as Colonel of the 13th Virginia Infantry. He fought with distinction at the Battle of First Manassas in July, and earned his general’s star soon after that engagement. He fought with equal fervor at the Battle of Williamsburg in May 1862 “with such spirit and determination that he was made a major general.” Hill fought against his old friend George McClellan – at the time the head of the Army of the Potomac – during the Seven Days battles around Richmond, known as the Peninsular Campaign.5

According to renowned historian Harry W. Pfanz, Hill was “a contentious fellow.” He often clashed with his superiors. At the end of the Seven Days’ battles, General Longstreet arrested Hill for his contention, insisting that Hill had not followed orders. Hill asked for a transfer, and the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, granted it.6

Hill did not fare better with his new superior, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. Like Hill’s mother, Jackson was overtly pious and deeply religious – something Hill had not encountered in Longstreet. Hill also disliked Jackson’s regimented ways, his tediously long marches and his lack of communication with his officers. Jackson promptly arrested Hill for not following his marching procedures, which sparked a feud that lasted for the rest of Jackson’s life.7

Hill redeemed himself in the eyes of General Lee when, on September 17, 1862, while Lee’s army had been precariously divided, the Battle of Antietam ensued. Hill, under orders and with his arrest put on hold, had successfully beaten the Union troops and secured their surrender at Harpers Ferry. He then marched so quickly to Sharpsburg that he made even Jackson proud. Hill reached the battlefield at Antietam, saving Lee’s army from a disastrous defeat. While the battle was nevertheless a Union victory, the end would have been far worse for the Confederates had Hill not arrived in such timely fashion.

The rancor between Hill and Jackson continued through the Battle of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Hill was with General Jackson when Jackson was accidentally – and mortally – wounded by men from Hill’s Light Division in the darkness on May 2, 1863. That evening, Jackson had ordered a flank attack in the coming darkness upon the Union camp. General Hill, aghast at the terrible wounding, forgot his anger. While trying to procure aid for the wounded general, Hill was also shot. The wound in the leg was not fatal, but rendered him unable to command for a time.8

Jackson’s death days later made it necessary for General Lee to reorganize his army. Where there had previously been two corps of over 30,000 men each, Lee divided his army into three corps. Longstreet maintained the First Corps, Richard Ewell took over Jackson’s Second Corps, and A.P. Hill was named to command the newly created Third Corps.

Lee's next objective was to invade the North. The plan culminated at a place called Gettysburg.

Hill’s incurable illness from his youthful visit to New York City returned with a vengeance as Lee’s army entered Pennsylvania. The disease had progressed to such a state that Hill was pale, weak, and in constant pain, especially when riding horseback. He also found it difficult to adjust to corps command – as he preferred fighting at the head of his troops. A decisive and militant fighter on the field in his earlier days of the war, Hill was not adept at administration, or at leading from behind.

In addition to his sickness, Hill suffered from a typical Confederate illusion at the time: overconfidence. When one of his brigade commanders, Johnston Pettigrew, hurried to headquarters in Cashtown on June 30 with news of a Union presence in Gettysburg, Hill and his friend from his West Point days, General Henry Heth, did not believe the news. Heth remembered that Hill told them that he had just come from General Lee’s tent, where scouts claimed that the bulk of the Union army was far away in Middleburg, Maryland and “had not struck their tents.”9

There was no stash of shoes at Gettysburg, but the Confederates, mistaking the shoe factory in Hanover, Pennsylvania for the nonexistent one in Gettysburg, planned to get the much-needed footwear. “If there is no objection,” Heth said to Hill, “I will take my division to-morrow and go to Gettysburg to get those shoes.” Hill replied, “None in the world.”10

As a result of ignoring Pettigrew’s correct sighting of the Union presence, General Heth ran his division into battle with the Union forces on July 1, 1863. While he had been instructed not to bring on an engagement, Heth ignored that order, which resulted in the Battle of Gettysburg. General Hill should have shared some of the blame for the oversight that embroiled the Confederacy in the battle that bled the Southern army of over one-third of its fighting force. Somehow, he escaped it.

As a corps commander, Hill remained behind the lines during the three-day battle. He exaggerated the Southern victory on the first day, claiming that the Union had been “routed

” and his troops had “annihilated” the Federal First Corps. The following two days proved that Hill had been woefully incorrect. Moreover, his own corps suffered heavy losses that day.11

Hill’s trusted subordinate, Harry Heth, had been severely wounded in the first day’s fight. On the second day, Hill lost another trusted division commander, General Dorsey Pender, to shrapnel fire. While Heth eventually recovered, Pender did not.

When General Lee failed to overrun the Union flanks on Gettysburg’s second day, he decided an assault upon the Union center on Cemetery Ridge might secure a victory. The newly arrived troops from Pickett’s Division, part of Longstreet’s Corps, were selected to make the charge. The rest of Longstreet’s men were worn out from the second day’s fight against the Federal left flank; they had taken heavy casualties as a result. Additionally, General Ewell’s troops had been engaged on July 2 and the morning of the 3rd trying to secure the Union’s right flank. They too, were exhausted and had suffered heavy casualties.

A.P. Hill’s corps had endured terrible losses on July 1, but during the next day they had not been heavily engaged. With both Heth and Pender unable to lead their divisions, two new commanders had been chosen: Johnston Pettigrew and Isaac Trimble. These generals, while personally capable and brave, were new to division command. Their troops did not know them. It proved an ill omen to such a pivotal fight.

Hill, still weak and ill, was not at his best when he called up his two divisions. Men from North Carolina, Mississippi and Tennessee made up the bulk of these troops.

Hill wrote little of the charge, only recording that his “reserve batteries were brought up, and put into position along the crest of the ridge…I was directed to hold my line with Anderson’s division and…to report [the troops] to General Longstreet.”12

Since Longstreet was a senior general to Hill, Old Pete was the man in charge. Hill, wearing his popular red shirt, watched the terrible charge and its equally terrible outcome.

Hill remained indisposed after Gettysburg, but ready for duty throughout the fall. His troops took heavy losses at Bristoe Station in October. By the new year, Hill was so ill that he was unable to command at The Wilderness or Spotsylvania – and the irascible Jubal Early took over the corps at the time. During the siege of Petersburg, Hill was on hand to help secure his corps deployment. He was happier too, as his wife and daughters moved to Petersburg to be near him. By the fall of 1864, Mrs. Hill was expecting their fourth child.

On April 2, 1865, the skeletal Confederate lines at Petersburg were broken by Union troops. In a desperate attempt to stem the blue tide, Hill rode to Lee’s headquarters to confer with the general. He then, against Lee’s wishes, rode toward Harry Heth’s headquarters through woods that were peppered with Federal troops.

Taking only an aide with him – which lends credence to the fact that he might have known he wouldn’t return alive – Hill encountered two Union soldiers, stragglers, in the woods. Ordering their surrender, he showed great temerity, as there were no troops to back him. The two men in blue quickly noticed, and fired their weapons. One bullet hit A.P. Hill in the heart and he fell dead to the ground, his hazel eyes forever closed.13

Hill’s aide returned to headquarters and gave Lee the devastating news. Lee tersely ordered a charge to procure Hill’s body, which was done. They took Hill’s remains to his expectant wife, and a funeral with full military honors was given that day. Hill was buried in the city cemetery in Petersburg. The body was later interred in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

Hill’s wife gave birth to a fourth daughter two months later, and named her Anna Powell Hill, or “little A.P.”. She died in childhood, like her eldest sister, Henrietta. Two daughters, Frances Russell and Lucy, lived to adulthood and married, but had no children. In addition, Kitty Hill, who mourned her husband for the rest of her life, refused to talk about the war or his role in it. Perhaps these are some of the reasons so little is known about A.P. Hill.14

The Confederacy died soon after Powell Hill's demise. Lee’s army surrendered at Appomattox seven days after Hill's death. Some historians have speculated that General Hill allowed himself to be killed rather than see his country collapse. “Ambrose P. Hill was one of the giants of Lee’s army,” wrote one newspaper correspondent, “and disputed with Longstreet and Ewell for the place of affections of the …people which Stonewall Jackson once held.”15

When Robert E. Lee died in the fall of 1870, the last person he mentioned in his unconscious mind was A.P. Hill, ordering, “Tell Hill he must

come up

” before his last words, which were “strike the tent.”16

Ill he often was, combative he certainly was, but A.P. Hill, the enigma of Southern generals, was a fighter whose courage under fire was legendary. One can only imagine how powerful a contender he might have been, had he not suffered physically for so much of the war.

Sources: A.P. Hill Family Tree, Ancestry.com. A.P. Hill Participant Accounts File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography

. Vol. 3, New York, 1889. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee

. Vol. 4, New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1935 (reprint, 1963). Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day

. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. The Richmond Whig, 7 April, 1865. The Richmond Whig, 10 April, 1865. The Richmond Whig, 11 Apr. 1865. Robertson, James I. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior

. New York: Random House, 1987. Rollins, Richard, ed. Pickett’s Charge! Eyewitness Accounts

. Redondo Beach, CA: Rank and File Publications, 1994. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders

. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

End Notes:

1. A.P. Hill Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Robertson, p. 5.

2. Pfanz, p. 115. Warner, p. 135.

3. Pfanz, p. 115.

4. Robertson, pp. 31-33.

5. Drake, p. 226. Warner, p. 135.

6. Robertson, p. 98. Pfanz, p. 116. Hill’s war record lists him as 5’10” tall – not little by any means. The diminutive sobriquet might stem from childhood since he was the youngest of his family, or his thin frame, or possibly, at least in the army, in part due to his inability to get along with his commanders.

7. Ibid.

8. Robertson, pp. 187-188.

9. Pfanz, p. 28.

10. Ibid.

11. A.P. Hill Participant Accounts, GNMP.

12. Rollins, p. 36.

13. Drake, p. 226. Richmond Whig, 10 Apr., 1865. A.P. Hill Family File, Ancestry.com.

14. Richmond Whig, 7 Apr., 1865. Richmond Whig, 11 Apr., 1865. Robertson, p. 321.

15. Richmond Whig, 11 Apr., 1865.

16. Freeman, p. 492.