The road to Gettysburg in the summer of 1863 was extremely hot and dusty. The Union Sixth Corps, the largest in the Army of the Potomac, marched from 10 p.m. on the night of July 1st to 5 p.m. in the afternoon of July 2, the last of the infantry in blue to reach the battlefield. As Meade’s largest corps containing about 16,000 men, they were “ a splendid corps

” and the rest of the Federals were glad they had arrived. Their commander, John Sedgwick, did not waste time with rest – although it would have been welcome after a nineteen-hour march in such conditions. Instead, he sent his men where they were needed. Some rushed to the Wheatfield to aid Crawford’s Pennsylvania Reserves. Some were dispatched to Culp’s Hill. The men with the Greek crosses on their jackets or caps were among the best of the veteran fighters. They were led by an equally exceptional commander, who expected nothing less. He was a man “but whom few can equal.” His men just called him “Uncle John”. 1

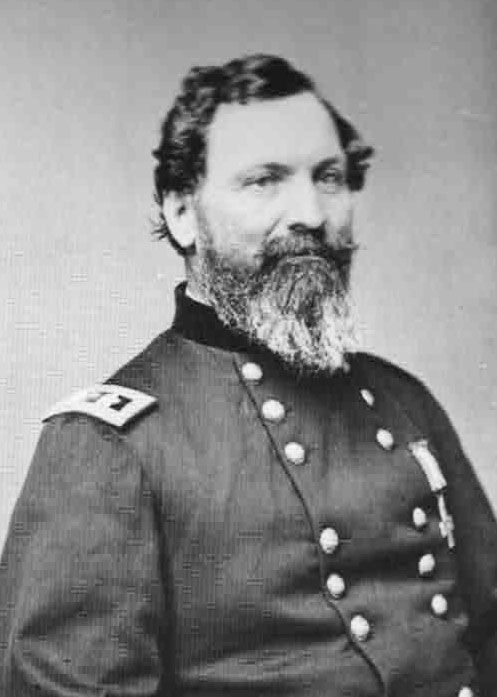

John Sedgwick was born on September 13, 1813, in Cornwall Hollow, a hamlet in the northwestern corner of Connecticut, the second son of Benjamin and Olive Sedgwick. He was named for an uncle who was a Major General in the American Revolution. Three sisters followed him, and the family, though not wealthy, was greatly respected in the small community. One youth, who often visited the family, remembered that John Sedgwick “like his father, was a large-hearted, large bodied man, with a large nature…There was a kindly, familiar, approachable way about the general…He kept in touch with the common people. He was big without dignity or artificial airs.” 2

Perhaps it was because he was named for a great military ancestor that John Sedgwick decided upon a military career. He taught school upon graduation from a local school, then at age twenty entered West Point Military Academy. He graduated there in 1837, with classmates Joe Hooker, Jubal Early, and Braxton Bragg. He spent the next several years fighting against the Seminole uprisings, and his sense of honor chafed at the way the tribes were often treated. In a letter to his only surviving sister, Emily, he wrote: “Half the murders that are committed on the plains and laid to the Indians, are committed by white men.” The nefarious and unjust dealings incensed the young soldier. 3

Sedgwick fought with distinction in the Mexican War, being brevetted twice for gallantry at the Battles of Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec. He ended the war with the rank of major. After that war, he transferred to the Federal Cavalry.

When the Civil War erupted, Sedgwick was the colonel of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, and was soon engaged at the Battle of First Manassas. Appalled at the behavior of his army, he protested in a letter to his sister that the men were “most disgraceful! We have lost everything, even our honor…whole regiments fled without giving a shot.” He, however, fought bravely, and was promoted to brigadier general in the U.S. Second Corps the following month. He fought in the Peninsula Campaign, also with distinction. 4

At the Battle of Antietam, General Sedgwick was ordered by the corps commander, General Sumner, to launch an attack in the West Woods. Without sufficient reinforcements, the Confederates counterattacked and killed or wounded half the division. Sedgwick, too, was shot three times, wounded in the wrist, leg and shoulder. Fainting from the loss of blood, he refused to leave the field for two hours, until he knew the remainder of his men were reinforced. 5

For several months, Sedgwick recuperated at his home in Cornwall Hollow. He soon grew bored with the inactivity, and said that “if he was struck again he hoped the wound would be fatal at once.” 6

A bachelor, Sedgwick felt that to marry during war time was a difficult thing for a wife and family to endure. Shortly before the Battle of Antietam, he turned 49 years old. 7

Segwick was engaged with his division at Fredericksburg, still in Sumner’s Second Corps. At the end of the year, Sumner, the oldest general in the Army of the Potomac, resigned. He was replaced by Darius Couch. With the new year, Sedgwick’s classmate, Joe Hooker, was given command of the army.

On May 1, Sedgwick and his troops were deployed near the town of Fredericksburg, and well positioned to take control of it during the Battle of Chancellorsville. With the wounding of Hooker, and the subsequent issues with the men in blue as General Robert E. Lee trounced them, Sedgwick was forced to leave the town and hurry to the aid of the army. He was deeply frustrated at the loss. His corps commander, Darius Couch, resigned in protest and told President Lincoln in no uncertain terms that Hooker was unfit for command. While Sedgwick did not go that far, he signed his name to a paper with other generals, giving his support to George Meade, and promised to serve under Meade, even though Sedgwick outranked him. 8

With Couch’s resignation, a new commander, Winfield S. Hancock, took over the Federal Second Corps. With the losses at Chancellorsville and the resignations of others, there were openings for higher command. General John Sedgwick was promoted to commander of the U.S. Sixth Corps.

The men of the Sixth Corps admired their new commander. They badly needed a morale boost after Chancellorsville, and Uncle John gave it to them. He was “ one of the oldest, ablest, bravest soldiers of the Army of the Potomac

,” one contemporary remembered, “ inspiring both officers and men with his fullest confidence in his military capacity. His simplicity and honest manliness endeared him, notwithstanding he was a strict disciplinarian…and his corps in consequence was one of the best in discipline and morale in the army.” 9

General Meade became the commander of the Army of the Potomac three days before the Battle of Gettysburg. Not yet aware of where the next battle would take place, he wanted Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps, the army's largest body of men, as the reinforcements. The men had already been marching in excessive heat and storms for many days. “ We have been marching every day over the worst roads and about the hottest days…that I have ever seen or felt

,” Sedgwick wrote to his sister, Emily. “ Many of our hardest marches have been made at night.” 10

One bright moment occurred during the march northward. Fellow officers from the Union Second Corps, knowing that Sedgwick had recently lost his trusty steed Tom, gave him a beautiful black horse, “ the finest in the Union army.” Sedgwick named him “Handsome Joe” and proudly rode him to Gettysburg. 11

When Sedgwick received the order to march toward Gettysburg, he embarked immediately. Instead of riding ahead of his soldiers, he remained with them. The corps arrived at Gettysburg from Manchester, Maryland at about five p.m. on July 2 – when the heavy fighting still raged. Sedgwick immediately dispatched his men to reinforce where they were needed.

Today, on the Gettysburg battlefield, monuments to the men of the Sixth Corps are identified by Greek crosses. They are placed in various areas, because the men were sent wherever they were needed, on both Union flanks, in the Valley of Death and along Cemetery Ridge. Sedgwick chafed at not being able to lead them personally, and said he “ may as well go home.” 12

Sedgwick was present at General Meade’s Council of War at Union headquarters on the night of July 2. He defended Meade and maintained that “ at no time in my presence did the general commanding insist or advise a withdrawal of the army.” He disliked Dan Sickles and Dan Butterfield, and considered them ungentlemanly. He vigorously defended Meade when Congress attempted to remove him from command after Gettysburg. 13

After Gettysburg, Meade and Lee were not engaged in a major battle for the remainder of 1863. During the Mine Run Campaign, however, there were skirmishes. Sedgwick’s men captured an entire Confederate regiment, including artillery and battle flags.

When General Ulysses S. Grant took over the command of all Union armies in early 1864, he decided that Lee’s army was the one to vanquish. The next battle that involved the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia was The Wilderness, the first battle of Grant’s Overland Campaign. Shortly before the battle, which occurred May 5-6, Sedgwick wrote to his sister. In it, he penned, “ If anything happens to me, you will remember how well I have always loved you. You will always believe that I have lived and shall die true to my country and my name.” 14

At the terrible battle, many generals fell, including Alexander Hays, James Wadsworth, John M. Jones, Micah Jenkins, and James Longstreet – although Longstreet survived his devastating wound. John Sedgwick survived unwounded, but The Wilderness was his last battle.

The perseverant Grant pursued Lee's troops after the battle, and the two armies prepared for a second contest near Spotsylvania Court House. On the morning of May 9, Sedgwick’s men deployed at the spot that later was known as the Bloody Angle. Overseeing the placement of artillery, Sedgwick was not in uniform, as the battle would not begin until the following day. Many of his troops had dug trenches and were already occupying them, ducking occasionally as snipers from the woods fired across the lines.

Always in good humor, Sedgwick strode past the men in the rifle pits and joked as one young soldier flinched at the sound of a bullet. “ Why what are you dodging for

,” he said. “ They could not hit an elephant at that distance.” 15

Immediately the zip of another bullet was heard, and John Sedgwick fell back, killed instantly. The bullet found its mark under his left eye, causing blood to course from his nostrils. His chief of staff, Martin T. Mahon, explained, “ It seemed to us who bent over him that if we could but make him hear and call his attention to the terrible effect his fall was having on our men, he would by force of his great will rise up in spite of death.” Spattered with the general’s blood, Mahon rushed to headquarters, where he found Generals Henry Hunt and Seth Williams, among other officers. They saw the stricken look on Mahon’s face and noticed the copious amount of blood on his uniform. Seth Williams approached him and said only, “ Sedgwick

?” Mahon was too overcome with emotion to answer. 16

May 9, 1864 was a quiet day on the battlefield, and for the Army of the Potomac it was a day of mourning. Soldiers fashioned a bier for the fallen general, and covered it with pine boughs. From all ranks of the army, men came to pay their respects, and the majority of them were in tears. “ Each one in their tent, old, gray-bearded warriors burst into tears and for some minutes sobbed like children.” It was noted that “ a great loneliness fell upon the hearts of all.” Another said Sedgwick's death “ cast a gloom over the army.” 17

The Sixth Corps fought like dragons the following day and for the rest of the war, but to Sedgwick’s men, the victories were empty without him there to lead them. Sedgwick’s body, along with Generals Hays and Wadsworth, were placed upon a train and taken to Washington. Sedgwick lay in state in Washington until he was taken to Connecticut for burial. Among the many flowers and honors bestowed, there was a small bouquet pinned to his uniform, which stated, “ To the Memory of General Sedgwick.” It was signed Mary Lincoln.

18

John Sedgwick was buried in his beloved Cornwall Hollow.

After the war, men from both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line still offered kind words in tribute to the slain commander. Fitzhugh Lee remarked, “ I always greatly admired the late John Sedgwick. At his death there were two mourners: his friend and his foe.” Wesley Merritt wrote, “ General Sedgwick, I am proud to say, was a good friend of mine…[I am] especially proud of General Sedgwick’s good will.” John Brooke said, “ General Sedgwick was loved by all who knew him.” Robert E. Lee noted, “ I knew Sedgwick well, and he would not have anybody about him except gentlemen.” 19

For many years, members of the Federal Sixth Corps visited the grave of John Sedgwick, and held an annual ceremony, usually on Memorial Day. A statue of Cornwall Hollow’s famous son was dedicated at the beginning of the new century, and a book of his letters was published by his surviving sister, Emily. As the general’s centennial approached, veterans raised money to place a monument of their esteemed commander at Gettysburg. In September, 1913, the equestrian of John Sedgwick, with his favorite horse, Handsome Joe, was dedicated at Gettysburg. The sculptor was the renowned Henry Bush-Brown. Inscribed on the base are the words “Beloved Commander

”. 20

John Sedgwick was the highest-ranking general officer of the Union to die in the Civil War. Only two Confederates outranked him: Lt. General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, and General Albert Sidney Johnston. 21

“ We soldiers loved him

,” said Captain D. C. Kilbourn at one of the annual graveside services, “ and we who knew his hand so firm, his heart so brave, his generous trust, and his faith so true: we loved him beyond the grave.”22

The John Sedgwick Memorial, with his horse "Handsome Joe", Gettysburg

(Author Photo)

Sources: America Battlefield Trust/Gettysburg, battlefields.org . Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography . Vol. V, Ancestry.com. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command . New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1968. The Hartford Daily Courant, 12 May, 1864. The Hartford Daily Courant, 14 May, 1864. The Hartford Daily Courant, 12 June, 1897. The Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903. The Hartford Daily Courant, 29 April, 1913. The Hartford Daily Courant, 28 May, 1922. Hyde, William. North America Family Histories, 1600-1900 . Ancestry.com. The Ottawa Free Trader, (IL), 02 July, 1864. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg, The Second Day . Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam . New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983. The Sedgwick Equestrian, Gettysburg National Military Park. Wagner, Margaret E. The Library of Congress Illustrated Timeline of the Civil War . New York, Boston, and London: Little, Brown and Company, 2011. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Historic newspaper accounts, all listed in sources, are found at newspapers.com .

End Notes:

1. Coddington, p. 356. The Ottawa Trader, 02 July, 1864.

2. Hyde, p. 328. The Hartford Daily Courant, 12 June, 1897.

3. Warner, p. 430. The Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

4. Ibid.

5. Sears, p. 227. Appleton, p. 450.

6. Hartford Daily Courant, 29 April, 1913.

7. The Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

8. Coddington, p. 36. Hartford Daily Courant, 12 May, 1864.

9. Appleton, pp. 449-450.

10. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

11. Hartford Daily Courant, 28 May, 1922.

12. Pfanz, p. 393. America Battlefield Trust/Gettysburg, battlefields.org.

13. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903. Pfanz, pp. 40-41.

14. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

15. Wagner, p. 184. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

16. Ibid.

17. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

18. Hartford Daily Courant, 14 May, 1864.

19. Hartford Daily Courant, 09 May, 1903.

20. Hartford Daily Courant, 28 May, 1922. Sedgwick Memorial, Gettysburg.

21. Sedgwick received the promotion to Major-General to date from July 4, 1862. John Reynolds, the second highest-ranking Union general to die in the war, was still a POW when Sedgwick received the promotion, though he also received that rank after his release in August. James McPherson received his promotion to Major-General in October 1862. All three were corps commanders when killed. Albert Sidney Johnston was an army commander when he was killed at Shiloh on Easter Sunday, 1862. He is the highest ranked general to die in the war.

22. Hartford Daily Courant, 12 June, 1897.