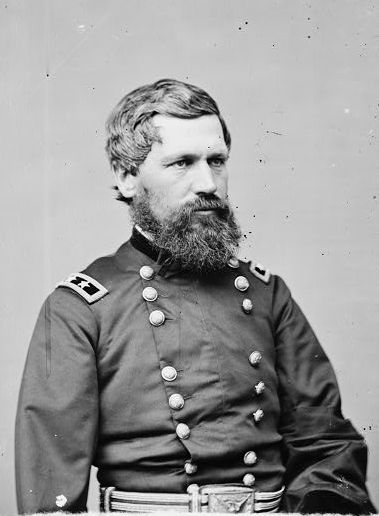

General Oliver O. Howard:

The Pious Soldier

by Diana Loski

Gen. Oliver O. Howard

(Library of Congress)

Monuments abound throughout the battlefield at Gettysburg. East Cemetery Hill boasts two equestrian statues of two Union generals who were there in July 1863. The one at the forefront represents the fearless Winfield S. Hancock, the commander of the Federal Second Corps, and one who was ubiquitous along the Union line on the adjoining Cemetery Ridge during the battle. The man on the memorial farther back is not as well known to history, but he was the one who placed Union troops on Cemetery Hill when his Eleventh Corps first reached Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. He was Gettysburg’s pious commander, Oliver O. Howard.

Oliver Otis Howard was born in Leeds, Maine on November 8, 1830, the eldest son of Rowland Howard and his wife, the former Elizabeth Otis. Rowland Howard died when Oliver was just nine years old, and he was sent to live with an uncle for much of his youth. Howard proved an eager pupil at Maine’s public schools, and taught school during summers to put himself through college at Bowdoin in Brunswick, Maine. At graduation, Howard wasn’t yet sure of his path, although he greatly admired his grandfather, Captain Seth Howard, who served in the American Revolution – and whom Howard knew as a boy. To help Oliver, his uncle, now a member of Congress in Maine, managed to get his nephew accepted to West Point in 1850.1

Howard was kindly, quiet, and had a “hearty integrity”, yet was not popular at West Point. During his first winter at the Academy, he fell dangerously ill; for a time it appeared he might not recover. While he was in the hospital, he received a gracious guest. “The Colonel Robert E. Lee paid me a visit, sat down by my bedside and spoke to me very kindly,” he remembered. Lee served as the Superintendent of West Point at the time. Coincidentally, his son Custis was a cadet at the same time, and Custis did not have any affection for Oliver Howard.2

Howard graduated 4th in his West Point class in 1854, where Custis Lee ranked first in the class. Others who graduated that year included future Gettysburg combatants Stephen Weed, William Dorsey Pender, and J.E.B. Stuart.3

Lieutenant Howard was placed with ordnance in the Federal army, and spent time in Florida against the Seminole uprisings there. While in Florida, he was converted to Christianity after seeing battles up close. During a revival in Florida, Howard walked up to the altar, proclaiming his faith for all present to see. From that time, he never wavered from being “deeply religious”. He considered resigning from the army and becoming a theologian. A year into his frontier duty, he wed his childhood sweetheart, Elizabeth Waite – and the need to support a family, combined with the oncoming clouds of war, kept him in the military. He spent the years immediately preceding the war as a math instructor at West Point.4

When war erupted in April 1861, Howard immediately offered his services to the Union. He was elected colonel of the 3rd Maine Volunteer infantry, but was promoted to temporary brigade command a month later. He commanded a brigade of three Maine regiments and one Vermont unit at First Manassas on July 21, 1861. Although the Union was soundly defeated at the Civil War’s first major battle, Howard secured a permanent promotion to brigade command in September. He was consistently brave in battle, yet was rarely popular with the men he led.5

On June 1, 1862, at the Battle of Seven Pines, Howard suffered a severe injury to his right arm that necessitated amputation between the elbow and shoulder. The wound resulted in a long recovery, which Howard spent in recruiting back in his home state of Maine. He returned to the front in time for the Battle of Antietam. After that fight, in which John Sedgwick was wounded, Howard attained the command of Sedgwick’s division in the Federal Second Corps. On March 31, 1863, Howard was given command of the U.S. Eleventh Corps. The former commander, Franz Sigel had resigned in protest to a reprisal after a loss in western Virginia. The men in the ranks of that corps resented their new commander.6

One soldier in the ranks described Howard as “soft spoken, kindly, and deeply religious.” He refrained from smoking, drinking alcohol, and never cursed or swore. He organized prayer meetings for the enlisted men in his spare time away from the fighting.7

General Sigel’s resignation came at a terrible time for the Union forces in the Army of the Potomac – who also learned there was a new commander at the helm. Joseph Hooker’s only battle in that capacity was the Battle of Chancellorsville, and the Eleventh Corps, with their new general, formed the Union’s right flank. Multiple fallacies, including the one in the highest command, created openings for an outnumbered Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Hooker pulled back Dan Sickles’ Third Corps, which formed the dividing line between Lee’s men, allowing them to flood the lines and push back the Federals. Men from Sickles’ corps noticed men in gray progressing through woods – elements of General Jackson’s troops – and mistakenly reported that movement as a retreat. The sun dipped below the horizon, and the Eleventh Corps put up their tents and began cooking their rations, isolated from the rest of the army. They received a horrific surprise attack by General Stonewall Jackson’s corps. The men, already dissatisfied with their situation without Sigel, and without back-up, were terrified and fled. The rout resulted in only one boon for the Union: in the darkness, one of Jackson’s own troops accidentally shot him, which several days later proved fatal.8

After Chancellorsville, both armies paused to regroup and replace the losses from their respective commands. In spite of the rout of his corps, Howard was not blamed for the incident, and retained command of the Eleventh Corps. As May turned to June in 1863, Lee’s men were on the move northward, and the Union army followed. As the two armies marched toward Pennsylvania, a new commander of the Union army was chosen: George Meade.

On the night of June 30, Howard and his men halted at St. Joseph’s Academy in Emmitsburg. That night, Howard received a message from wing commander General John Reynolds, asking Howard to visit him at his headquarters at Moritz Tavern near Gettysburg. Howard dined with Reynolds and his staff, after which the two generals studied maps of the area. Reynolds told Howard to keep the roads cleared of supply trains, should the men be needed to hasten to Gettysburg.9

As it turned out, Gettysburg was indeed the place of battle.

General Howard, aware of the proximity of the other Union corps, expected Generals Slocum and Sickles to be available for fighting at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863 – though they did not arrive in time for fighting that day. John Reynolds, who had engaged in the battle that morning, was killed while at the head of his troops. Howard, who was a corps commander and not necessarily supposed to be in the middle of the engagement, spent most of the first day of battle on Cemetery Hill. Some of Reynolds’ men averred later that Reynolds had told Howard to secure the hill, but Howard claimed he never got the message. As a West Point graduate, he too would have known the essence of that important hill. Whether Reynolds’ missive reached Howard or not, Howard did secure Cemetery Hill – a deed for which he later received the thanks of Congress.10

On the first day at Gettysburg, both armies were arriving, and as certain contingents came to the battlefield, they were thrown into the fray. More Confederates arrived that day than Union men, and with the strength of their numbers they pushed the Federals back through town. Howard’s men, who fought against Dick Ewell’s corps north of town, were in a frenzy trying to escape the surrounding men in gray and butternut. When a plea came to Howard from the brickyard area north of the square for reinforcements, Howard refused to comply. He needed the troops on Cemetery Hill to stay there. “Hold out, if possible, a little longer,” Howard said, “for I am expecting General Slocum at any moment.” Without reinforcements, and waiting for the general who did not arrive, many of Howard’s men were killed, wounded, or captured.11

When the exhausted Union survivors of the First and Eleventh Corps reached Cemetery Hill, Howard was there to restore order. He was joined by another commander, General Winfield S. Hancock – whom General Meade had put in charge until he got to Gettysburg.

Waiting for Meade’s arrival, Howard made the Cemetery gatehouse his headquarters, which was the home of civilian Elizabeth Thorn and her family. Her husband was fighting for the Union in Virginia, and she had taken over the task of operating the Evergreen Cemetery. She offered dinner for Generals Howard, Slocum, and Sickles. Mrs. Thorn remembered General Howard’s concern for her and her family. “When I give you orders to leave the house, don’t study about it, but go right away.” Mrs. Thorn’s three boys watched General Howard in fascination as the three generals spoke about the battle. They were amazed at General Howard’s empty right sleeve, which “flapped in the air” during his expressions of the day to the other two generals.12

The procurement of Cemetery Hill, which formed part of the Federal right flank, and the ensuing fishhook line, proved fortuitous for the Union forces. It placed the hill in jeopardy, however, on the evening of July 2, when General Lee ordered an attack on the Union flanks. Realizing that his troops were in danger again, Howard sent a missive to General Hancock, asking for a brigade to join his corps, already thinned in ranks due to the first day’s battle. Hancock had also seen the danger, and sent Colonel Samuel S. Carroll’s brigade, who helped shore up the blue line.13

General Howard remembered the terrible night with “hostile cannon...with their fearful roar” and “the indescribable peal of musketry fire” as the hill contained “that sad spectacle of broken tombstones, prostrate fences, and the ground strewn with our own wounded and dead companions.”14

After the defeat of Pickett’s Charge the next day, the Union forces held, and Gettysburg proved a Union victory. The war, however, was still far from over. In the fall of 1863, the Federal Eleventh and Twelfth Corps were sent to Tennessee (and later Georgia) to fight. Howard and his corps participated in both the Chattanooga and Atlanta Campaigns, and performed well. Army commander James McPherson was killed during the fight in Atlanta in July 1864. General William T. Sherman assigned General Howard to replace McPherson as commander of the Army of the Tennessee. Howard led the army and served as a wing commander under General Sherman, in the March to the Sea. When the war ended, Howard was one of the top ranked generals, and was given the post-war rank of brigadier general.15

On July 4, 1865, General Howard found himself again at Gettysburg, upon the same hill where his corps had fought two years earlier. The occasion was the laying of the corner stone of a new monument to the soldiers whose remains were beneath the hill in the new National Cemetery. General Howard gave one of the dedicatory addresses on that day. He said of the yet future memorial to the soldier: “It embraces a patriotic brotherhood of heroes…Cost what it may, he toils on.” He said to the audience that day, “Oh, that you had seen him as I have done…without one faltering step, charging in line upon the most formidable works…You could then appreciate him and what he has accomplished as I do.”16

It was Howard’s post-war work that has earned him the most credit. Shortly after war ended, President Johnson gave Howard a significant post as the president of the Freedman’s Bureau, a part of the War Department, helping the recently emancipated slaves a place to work, and improve their lives.17

Howard realized that education was essential to freedom and prosperity. He established Howard University in Washington D.C. in 1867 for minority students, a college that is still extant today. In 1897, he founded Lincoln Memorial University in the mountains of Tennessee, in order to help educate the poor of that region.18

General Howard continued to serve the U.S. government, including a brief stint as superintendent of West Point. He retired from service in 1894.19

Howard and his wife, Elizabeth, were the parents of seven children. Their firstborn, Guy, chose the military for his career as his father had done. During the Spanish American War in 1899, Guy was killed in action in the Philippines. Howard later said that his son’s death “is the heaviest blow that our family has had.”20

Howard remained active, prolifically writing books and articles on the war, and speaking at reunions and state functions. The family resided in Burlington, Vermont. On Valentine’s Day, 1905, he and his wife celebrated their 50th anniversary. It was a privilege denied many who had fought in the war.21

On October 26, 1909, Howard was at his home, quietly sitting in a chair, when he was suddenly seized by a heart attack. A doctor was summoned, but Howard died before help could arrive. He was just days from his 79th birthday. He was the last of the Union army commanders. He is buried in Burlington, Vermont.22

“He was one of the more affable and social of men,” claimed one who knew him, “an orator of ability.”23

Another described Howard as “the true type of Christian soldier, conscientious but modest.”24

On East Cemetery Hill in Gettysburg, near the spot where his headquarters was located, Howard was honored by the citizens of Maine with an equestrian statue. The monument was dedicated in 1932. The general is depicted on his horse, firm and prepared to fight, and without his right arm.25

From West Point to Gettysburg to beyond the war, Oliver Howard remained steadfast in standing for what he believed. Perhaps his greatest work was after the war, in helping freed slaves to live in a new nation, and especially with the university that still bears his name.

The Howard memorial, Gettysburg

(Author photo)

Sources: Appleton, John, ed. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. III. New York: Appleton and Sons, 1887. The Bristol Herald, Nov. 4, 1909. The Brooklyn Citizen, Dec. 15, 1907. The Burlington Transcript-Telegram, Oct. 27, 1909. “Ceremony for the Laying of the Cornerstone of the Soldiers Monument”. Gettysburg, PA: Aughinbaugh & Wible, Book and Job Printers, July 4, 1865. Copy, Gettysburg National Military Park. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Hefferman, John Paul. “Howard University: 100 Years Ago by a General from Maine”. Portland Press Herald, May 7, 1967. Howard Equestrian: National Park Service: nps.gov/get/howard. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Thorn, Elizabeth. “A Woman’s Thrilling Experience of the Battle”, Civilian Accounts File, Adams County Historical Society. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964 (reprint, 1992). Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1959 (reprint, 1987). Historical newspapers found at newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 237. Burlington Transcript-Telegram, Oct. 27, 1909.

2. Hefferman, p 63. The Brooklyn Citizen,Dec. 15, 1907. Warner, Generals in Gray, p 179. Pfanz, p. 131.

3. Pfanz, p. 131.

4. Appleton, p. 278. Hefferman, p. 63. Pfanz, p. 131.

5. Hefferman, p. 63. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 237.

6. Ibid.

7. Hefferman, p. 63.

8. Coddington, pp. 33-34. Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 152. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 446.

9. Pfanz, pp. 47-48.

10. The Bristol Herald, Nov. 4, 1909. Pfanz, p. 136. Coddington, p 702.

11. Coddington, pp. 322-323. Pfanz, p. 294.

12. Thorn, p. 4.

13. Coddington, p. 438.

14. “Ceremony for Laying the Cornerstone”, July 4, 1865.

15. Warner, Generals in Blue, pp. 238, 308.

16. “Ceremony for Laying of the Cornerstone, July 4, 1865.

17. Appleton, p. 278.

18. Burlington Transcript-Telegram, Oct. 27, 1909.

19. Ibid.

20. Hefferman, p. 63. Burlington Transcript-Telegram, Oct. 27, 1909.

21. The Brooklyn Citizen, Dec. 15, 1907.

22. Burlington Transcript-Telegram, Oct. 27, 1909.

23. Ibid.

24. The Brooklyn Citizen, Dec. 15, 1907.

25. nps.gov/get/howard.