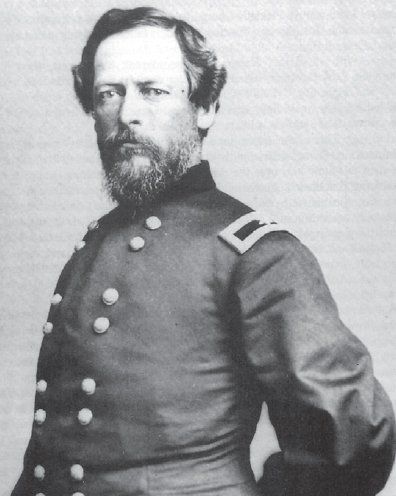

Samuel Kosciusko Zook was born to be a soldier, as his middle name implies. While originally it appears that Kurtz was his middle name, it was changed to Kosciusko, after the Polish military leader Tadeusz Kosciusko, who aided Washington’s army in the American Revolution.2

Zook was the eldest child of David and Eleanor Zook, who were Mennonites living in Tredyffin, Chester County, Pennsylvania. He was born on March 27, 1821. Eight siblings followed: David, Elizabeth, Hannah, Mary Emma, Jacob, Charles (who died an infant), Thaddeus, and Ellen.; but Sam was the pride of his doting father. When Sam was still a young child, the family moved to the farm of his maternal grandparents, near Valley Forge. There the Zook children had the run of the vast, old winter camp, with the eldest son conducting army drills with his siblings, and arresting them when they failed to execute proper procedure.3

After an education in the public school system, Samuel enlisted in the local militia – which was what most young men did at that time. He moved to New York City, and made a good living working for a telegraph company. By the time Civil War commenced, Zook was the Superintendent of the Washington & New York Telegraph Company. He was also a lieutenant in the New York City militia. He was forty years old when war commenced, and a confirmed bachelor. He offered his services along with the rest of the men in the militia. They became the 6th New York Infantry.4

When the new three-month regiment was called up, Zook was suffering with recurring rheumatism, but he joined the troops by the following month. When in September the three-month enlistment ended, Zook was instrumental in organizing the 57th New York Volunteer Infantry – and was made its colonel.5

Zook and his regiment fought in the Peninsular Campaign. He narrowly escaped death at the Battle of Fair Oaks, when one of his men captured a Confederate soldier who was aiming his musket at the commander. He missed the Battle of Antietam due to another attack of rheumatism, but was in the fight at Fredericksburg. In temporary command of a brigade, Zook and his troops acted with great temerity on Marye’s Heights. Many of his men fell that day – 527 of them, and Zook was among the wounded. General W.S. Hancock, impressed with Zook, recommended him for promotion. Zook received his brigadier’s star in March, 1863.6

In a letter home, Zook recalled seeing the wake of the field on a cold December night. “I never realized before what war was. I never before felt so horribly…To see men dashed to pieces by shot & torn to shreds by shells…is bad enough…but to walk alone among the slaughtered brave in the ‘still small hours’ of the night would make the bravest man living ‘blue’.” 7

During the winter months, as 1862 turned into 1863, Zook worked to drill and perfect his brigade. According to one from his brigade, “he was strict, impartial, and rigidly just.” Another remembered, “he had no patience with a man that neglected duty; was blunt, sometimes severe; yet good-hearted….he was absolutely without fear.”7

Zook was officially the commander of his brigade, the Third Brigade, First Division, Second Corps at Chancellorsville on May 1, 1863. He led them to Gettysburg, in his home state, for the next great battle. Three of his regiments hailed from New York, including his original command, the 57th New York. He also led the 52nd New York, the 66th New York, and the 140th Pennsylvania Infantries.

When Zook arrived in Gettysburg, a young private appeared in his tent, asking the general to send his money to his family, as he felt he would be killed in the coming fight. Noticing the callow features of the boy, Zook took pity on him and told him to spend the time with the ambulances instead. The boy insisted on staying with the regiment; Zook agreed to take the funds. Soon, Zook too, felt a terrible foreboding. He sent for the private and told him, “I have the same sensations as you – that I will be killed – and you had better take the money and give it to someone else.”8

The men in Hancock’s Second Corps, of which Zook and his men were part, stared incredulously from Cemetery Ridge on the afternoon of July 2, 1863, as men from Sickles’s Third Corps vacated their position on Zook's left and redeployed – against orders – about a mile to the front. They were soon in terrible trouble. The Confederate forces, led by General Longstreet, had arrived on Seminary Ridge, facing them. They promptly attacked, and Sickles’s troops were “in the air” – alone, and without support. General Hancock quickly ordered the First Division under General Caldwell into the fight. The four brigades included Zook and his intrepid troops.

General Zook was in the fight before the rest of his division. He had encountered Major Henry Tremain, a messenger from General Sickles, on Cemetery Ridge. Zook noted that Tremain attempted in vain to hide his frantic countenance when the two approached one another. The gravity of the situation was obvious. “Sir ,” Zook said to Tremain, “if you will give me the order of General Sickles, I will obey it.” Major Tremain quickly responded that General Sickles wanted him to file his brigade to the right and head for the Wheatfield. General Zook immediately called up his troops.9

Sickles’s men were already rapidly retreating when Zook’s Brigade arrived on the edge of the Wheatfield, heading toward the Stony Hill. The general, never one to shirk duty, rode to the front of his men. Through the acrid smoke and deafening noise and confusion, no orders could be heard or given. Colonel Chapman, who later replaced Zook as commander of the 57th New York, remembered, “it was a severe attack ”, as men in gray seemed to surround them. As Zook cleared the road, he suddenly reared in the saddle. He had been shot by “a minie ball [on] the left side of the stomach, perforating his sword belt, and lodging in the spine.” His aide caught him and helped him off his horse. Zook said to him, “It’s all up with me, Favill.”10

The mortally wounded general was taken to a field hospital nearby. There a surgeon pronounced what Zook already knew – he would soon die. The following morning, July 3, he was moved to a place where he would be more comfortable, to a farmhouse on the Baltimore Pike. The owners had fled.11

“He was cool and composed to the last. About fifteen minutes before his death he turned and quietly asked the doctor – after hearing those who had bid him hope – about how long he had to live. A little while previously, he had requested his aide, Lieutenant Favill, to ascertain and let him know how the action was going. The latter officer reported that the bands had been ordered to the front, the flags were flying, and the enemy in retreat. ‘Then I am perfectly satisfied,’ said the general, ‘and ready to die.’” He died within minutes of the news.12

General Zook’s body was placed on a train in Westminster, Maryland and returned to his grieving parents in Chester County – not an easy task in the July heat and in the midst of a desolated battlefield. After a funeral at his parents’ home, a request came from his friends and colleagues in New York City, asking for a funeral for him there. His body arrived by train on July 13.13

As if the misfortune of the general’s death was not enough, the day his corpse arrived in his adopted city, the terrible New York Riots ensued. As his funeral began on Tuesday, July 14, hordes of angry citizens, part of the struggling working class, disrupted it. When his cortege passed through Broadway and the Bowery, the military escort was forced to leave the funeral and attempt to quell the unrest.14

“On the lid of the coffin were the sword, sash, cap and belt of the deceased general, besides a beautiful wreath of flowers ,” wrote one journalist. Among the general’s pall bearers were the famed Irish Brigade founder Thomas Meagher and future President Chester A. Arthur, who served as a military leader in the city during the war. The body was returned to Pennsylvania for burial in Montgomery County. 15

There would be another loss for the Zook family. David Zook, broken-hearted, never recovered from the loss of his son. He died just weeks later.16

Near the Wheatfield Road stands a narrow obelisk of granite. It marks the place near the spot where General Samuel K. Zook fell in the fight for the Wheatfield. It was placed there by GAR Post #11, named for the general, in 1891 – when he would have been, had he survived, seventy years old. War, however, seems to always rob its soldiers of the chance to grow old.

Samuel Zook was one of innumerable men who sacrificed everything for his nation. From Valley Forge into the jaws of war, Zook definitely fulfilled his destiny without fear, even though he knew death was coming that day. He had the comportment since his childhood at Valley Forge of a born soldier, which he bravely proved at a place called Gettysburg.

Sources: Ancestry.com: Zook Family Tree. Gambone, A.L. The Life of General Zook . Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 1996. “General Tadeusz Kosciuszko”, Smithsonian Magazine: smithsonianmag.com . Letter, Samuel Zook to E.I. Wade, 16 Dec., 1862. General Zook Personal Participants File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). The New York Daily Herald, 12 July, 1863. The New York Daily Herald, 14 July, 1863. The Story of a Regiment: The Military Services of the Fifty-Seventh New York Volunteer Infantry . Chapter XIII, pp. 177-178. Fragment, found in Zook Family File, Ancestry.com. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. New York Herald accessed through newspapers.com.

The Zook Memorial, Gettysburg

(Author Photo)

End Notes:

1. Story of a Regiment

, p. 177. Ancestry. com. An en echelon attack means a progressive attack. It comes from the French word for ladder.

2. “General Tadeusz Kosciuszko”, Smithsonianmag.com. Zook Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

3. Warner, p. 576. Gambone, p. 10.

4. Pfanz, p. 73. New York Daily Herald, 12 July, 1863. Zook was also an inventor and had fashioned a device to improve the telegraph, which was later patented.

5. Ibid.

6. Gambone, p. 36. Warner, p. 577.

7. Letter, Zook to E.I. Wade, 16 Dec., 1862.

Zook File, GNMP.

8. Gambone, p. 4.

9. Ibid., p. 10.

10. New York Daily Herald, 12 July, 1863. Pfanz, p. 277.

11. Ibid. pp. 24-25.

12. New York Daily Herald, 12 July, 1863.

13. Gambone, pp. 181-182.

14. New York Daily Herald, 14 July, 1863.

15. Ibid.

16. Zook Family Tree, Ancestry.com.