The Year 1925

by Diana Loski

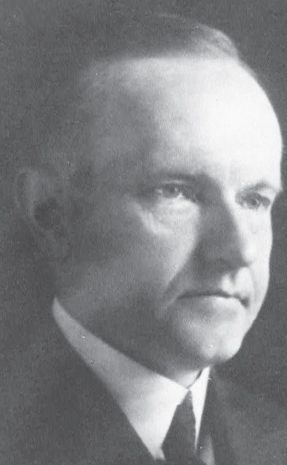

President Calvin Coolidge

(Library of Congress)

A century ago, the year 1925 began on a Thursday, and it was an impressive year.

The vestiges of World War I and the deadly pandemic of the Spanish influenza had dissipated, and the people of the United States and the world wanted to look ahead.

Calvin Coolidge, who had taken over the Presidency since the sudden death of Warren Harding in 1923, was handily reelected in 1924. His Vice-President, Charles G. Dawes, was the son of Civil War veteran and Gettysburg combatant Rufus Dawes. The two men worked to bring financial security to the nation after the debt incurred from the recent war. Vice President Dawes received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925, in fact, for his aid in helping Germany to manage the daunting reparations they incurred from the Treaty of Versailles after World War I.1

In 1925, Germany suffered great financial setbacks due to the previous war. Riots and unrest occurred, including a former combatant from the Kaiser’s army named Adolf Hitler. Having attempted a government coup in 1923, Hitler, who was the leader of the new Nazi party, was arrested and imprisoned. While behind bars, he wrote the book Mein Kampf (My Fight). In 1925 he was out of prison and the first volume of his book was published to great acclaim in Germany. He worked tirelessly to unite his party, and voiced a promise of prosperity. He averred that he also wanted peace – a declaration that even then was a blatant deception.2

While debt soared across the Atlantic, the people of Europe heeded more drastic leaders for their post-war situations, in addition to the notorious Hitler. In Italy, the dictator Benito Mussolini rose to power in 1925. In the Union of Soviet Socialists Republic (the USSR), Joseph Stalin became the new Secretary General of the Communist Party and the leader of that large Euro-Asian nation. He replaced Vladimir Lenin, who had died in 1924.3

In the summer of 1925, Dwight D. Eisenhower left Panama, where he had been stationed for two years, to enter command school in Leavenworth, Kansas. He doubled down on his studies – knowing he had only a year to complete the course that normally took much longer. He would graduate first in his class in 1926.4

That same year Nellie Taylor Ross became the first female governor of the United States. She was the widow of the governor of Wyoming, and was elected to the office in his place. She served for just one year, and was not reelected in 1926.5

Other newsworthy events that took place in 1925 included an earthquake in Santa Barbara, California, and deadly tornadoes that destroyed the tri-state area of northeastern Missouri, southern Illinois and southern Indiana. Nearly seven hundred people were killed by the tornadoes, with over two thousand injured.6

During the summer of 1925, the days of the Battle of Gettysburg that had occurred in 1863 matched those days sixty-two years later: Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. Independence Day fell on Saturday that year – just as it had in 1863.

In Gettysburg, baseball great Eddie Plank had retired from professional baseball, and spent the year helping his brother, Ira, coach Gettysburg College’s baseball team. He and Ira planned to open a garage in Gettysburg on the site of their father’s old store. And, while the legendary pitcher had retired from professional sports, he still played for the Bethlehem Steel League – and was their star pitcher. A left-handed “southpaw” pitcher, Plank was nicknamed “the Grim Reaper” as his pitches were often no-hitters. One hundred years ago, he lived on Carlisle Street in Gettysburg with his wife, and their son, Eddie Jr.7

In 1925, the Majestic Theater opened in Gettysburg, and celebrates its centennial this year. That same year was an enormous one for the silver screen. Films like Phantom of the Opera and Rin Tin Tin were among the favorites of 1925.

The middle of the 1920s ushered in The Jazz Age. Jazz musicians Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington debuted that year, with their new style of music. The Charleston, the new dance of the age, was born in 1925. In order to master the dance, women needed freer clothing styles. Waistlines and corsets disappeared and hemlines rose accordingly. These women, with short dresses and bobbed hair, were known as Flappers. The age is well captured by one of the year’s bestselling novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby.8

In the autumn of 1925, the yet unfinished Mount Rushmore was dedicated in Keystone, South Dakota. It was not even started when the dedication occurred. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum attended with his thirteen-year-old son, Lincoln. Borglum had received permission from Congress for the massive undertaking, which would not begin until 1927 and was not finished until 1941. Borglum’s son was the one who finished the immense sculpture, as the famed sculptor died in 1941.9

In 1925 Walter Chrysler formed the Chrysler Corporation. Norway changed the name of its capital Christiana (after their beloved 17th century queen) to Oslo. Sears and Roebuck opened its first store in Chicago, Illinois. New York City was proclaimed the largest city in the world. Scotch tape and potato chips were invented and crossword puzzles became popular – and were found in local newspapers. In Great Britain, scientist John Baird showed the first images broadcast by screen – the precursor of the television.10

Some who passed on that year included nationally acclaimed lawyer and statesman William Jennings Bryan, Chinese leader Sun-Yat-Sen, Mexican outlaw Pancho Villa, and British citizen Alexandra Kitchin – she had been the model for whom author Lewis Carroll had fashioned his young heroine in Alice in Wonderland. The novel had been published in 1865.11

Some who were born in 1925 included future British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, future First Lady Barbara Pierce Bush, and actor Paul Newman.

How quickly a century passes, yet it is uncannily strange that after so many years, so many issues remain the same.

Sources: Eddie Plank File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Eisenhower, Dwight D. At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. National Park Service: Eastern National, 1967. Grun, Bernard. The Timetables of History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991 (Reprint, first printed in 1946). Shaff, Howard and Audrey Karl Shaff. Six Wars at a Time: The Life and Times of Gutzon Borglum. Sioux Falls, SD: The Center for Western Studies, 1985. Whitney, David C. and Robin Vaughn Whitney. The American Presidents. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1993.

End Notes:

1. Whitney, p. 255.

2. Grun, p. 488.

3. Ibid., p. 489.

4. Eisenhower, p. 202.

5. Grun, p. 488.

6. Ibid.

7. Eddie Plank File, ACHS.

8. Grun, p. 489.

9. Shaff, p. 228.

10. Grun, p. 488.

11. Whitney, p. 435. Grun, p. 489.