John Buford's Last Days

by Diana Loski

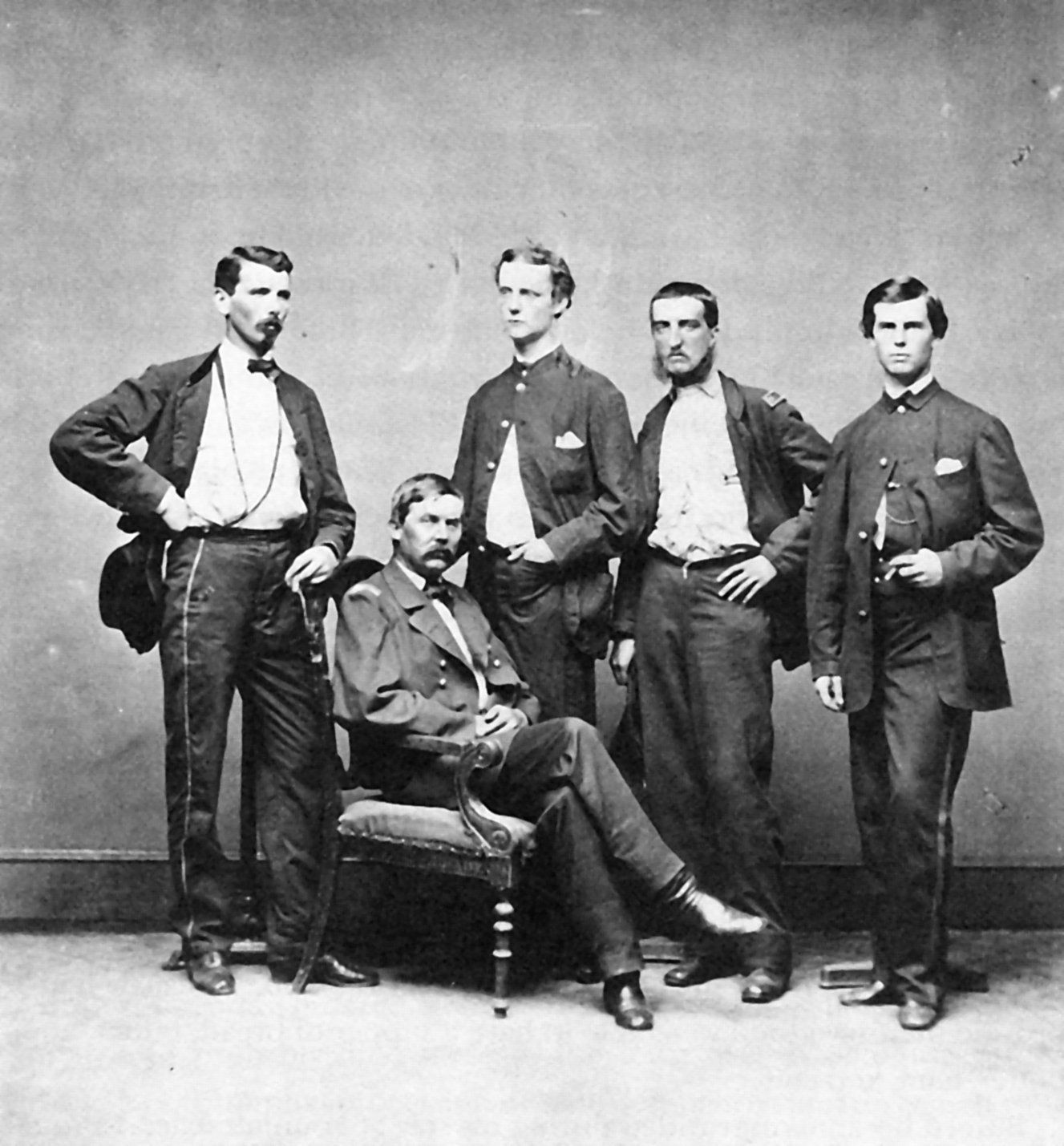

John Buford, seated and his staff, 1863

(Library of Congress)

The numbers continuously change as to how many soldiers perished in the Civil War – from just over 600,000 to nearing 800,000 deaths. Whatever that terrible number may be, one thing is certain: that more participants of that worst of American wars perished from disease than from wounds. One of those was the incomparable Union General John Buford.

Buford, who was named for his father, John Buford, Sr., was instrumental in securing the ground upon which the Union army deployed during the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg in the early summer of 1863. He was not wounded or killed in that battle, but he nevertheless did not survive the year.

Born in Kentucky on March 4, 1826, Buford’s early life, in some ways, mirrored that of Abraham Lincoln. Like Lincoln, he lost his mother when he was just a child – at eight years old. Like Lincoln, his family moved to Illinois. Buford’s father, who farmed and dabbled in local politics, kept horses; his namesake son excelled at horsemanship and was well known for his ability to ride at a young age. Inspired by his elder half-brother, Napoleon, John Buford secured entry to the prestigious West Point military academy. He graduated at the middle of his class in 1848, and spent his pre-war years in service on the frontier. In 1854 he married Martha Duke, whom he affectionately called “Pattie”. Two children were born to the couple, and unfortunately neither survived to adulthood. 1

When war erupted in the spring of 1861, he received an offer from the governor of Kentucky to serve as an officer in the Confederate army. Buford refused, saying to fellow officer John Gibbon, “ I was a Captain in the United States Army and I intend to remain one!

” 2

John Buford began the war as a major, and served in the office of the U.S. Inspector General in Washington. He chafed under the inactivity and longed to serve at the front. In the summer of 1862, General John Pope of the newly formed Union Army of Virginia liberated Buford by giving him command of that army’s Federal cavalry.

The condition of the Union cavalry at that time bordered on the ridiculous, as the majority of Union troops hailed from the city. They were no match for the South’s farm boys who, like Buford, had been around horses since they were old enough to walk. Buford worked his command tirelessly, and by August the cavalry performed well. They were tested at the Battle of Second Manassas on August 30th – and the Union troops were badly beaten, largely because General McClellan of the Army of the Potomac refused to come to Pope’s aid in time. Pope was relieved of command, and the Army of Virginia ceased to exist. The troops were absorbed back into the Army of the Potomac – which had been McClellan’s plan all along.

Buford was severely wounded in Second Manassas, in fact, for a time he was reported killed in action. He survived, and returned to the army in time for the Battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg. Back in brigade command, Buford served under General George Stoneman, an equally capable commander and Buford’s friend from West Point. 3

At the start of 1863, Joe Hooker was named as commander of the Army of the Potomac. He replaced the ineffective Burnside (who had in turn replaced the calculating McClellan after the Battle of Antietam). Stoneman was made the head of the Union cavalry, and Buford was happy to serve with him. Buford was always passed over for promotion, in part due to the fact that he was a Kentucky native. He did not seem to mind. Always circumspect and of few words, Buford was someone “not to be trifled with”. Though strict, he was a favorite with the men he served, both those he commanded and those with superior rank. 4

Like Burnside before him, General Hooker was a genial commander and the men liked him, but he was incapable of delivering a victory on the battlefield. His great loss came at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 1 and 2, 1863. Hooker had sent Stoneman and his men on a raid (known famously as Stoneman’s Raid) close to Richmond to harass Lee’s rear. While the raid was successful, Stoneman, Buford, and the rest of the cavalry had not been present when Lee attacked Hooker at Chancellorsville. Like most incompetent leaders, Hooker blamed Stoneman for the loss. A furious Stoneman promptly resigned. He returned to Washington to serve there as chief of cavalry. 5

There was now an opening for Stoneman’s replacement, and the overwhelming majority of the cavalry hoped John Buford would command the Federal cavalry. It was not to be. The more politically connected Alfred Pleasonton was named, and Buford quietly returned to his brigade. The opening, however, created a need for a new division commander, and John Buford, in the weeks before Gettysburg, received the promotion.

It was perhaps providential that John Buford was the commander in the field in the days and hours before the Union and Confederate troops clashed at the crossroads in southern Pennsylvania. Buford’s experience, devotion to his cause, and expert military understanding of the value of ground prepared him as he surveyed the placement of Lee’s troops in the nearby foothills of the South Mountains. Because the Union cavalry had, until recently, been woefully inexperienced, Lee’s men believed that they had successfully invaded Pennsylvania without the Union’s knowledge. Buford knew exactly where they were, and realized what would be the outcome at Gettysburg. However, Buford was concerned about the news that Joe Hooker had been replaced as army commander. The new general was George Meade. It was not a fortuitous time for a new leader.

On July 30, as Buford’s troops entered Gettysburg to great fanfare, young Daniel Skelly noticed Buford on his horse, Grey Eagle, near the Eagle Hotel on Chambersburg Street. “General Buford sat on his horse in the street in front of me,”

he remembered , “entirely alone, facing to the west and in profound thought.” 6

Realizing that the Confederate troops were nearer to Gettysburg and its high ground than the Union army, Buford devised a plan to hold the men in gray until the boys in blue could reach the town. He secured the permission to hold the position from General Meade; Buford's friend General John Reynolds promised to hurry his infantry corps to Gettysburg in the morning. Knowing that his former friend from West Point, Harry Heth, led the Confederate infantry into Gettysburg, Buford understood that Heth would easily take the bait and fall into battle. Buford saw that Heth led with his two weakest brigades, which were commanded by non-West Point commanders Davis and Archer. Buford instructed his cavalry to dismount, hide their horses behind McPherson’s Ridge, and fight the oncomers like infantry.

Buford told brigade commander Colonel Thomas Devin, “They will attack you in the morning and will come booming….You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own.” 7

The first day of the Battle of Gettysburg worked to the Union advantage, just as John Buford had predicted. Heth disobeyed Lee’s order to avoid an engagement and quickly fought back. The two leading Confederate brigades did not deploy well and suffered tremendous casualties – brigade commander Archer was, in fact, captured. Davis allowed his men to deploy in the unfinished railroad cut west of town and many of his men were either shot down or captured. While the Union suffered terrible losses – including the death of John Reynolds – and the subsequent loss of the first day’s position, the Federals nevertheless secured the high ground south of Gettysburg, and defiantly stood between Lee’s army and Washington. Gettysburg was an ultimate Union victory, and it was a decisive one. While many heroic men secured the victory, John Buford – who had only months left to live – had laid the groundwork.

Lee’s escape into Virginia had a negative effect on the Army of the Potomac, and Buford was no exception. In August, he was dealt another blow: his daughter, named Pattie after her mother, died at age six. He spent the fall in continued service, riding to find the army in gray and attempting to exploit any advantage for the Union. Time after time, like Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg, Buford’s tireless surveillance came to nothing for the Federals. He confided to General Pleasanton that he was “ disgusted and worn out.” 8

At age 37, Buford already suffered from rheumatism. With the coming chill and the misfortune of drinking water that was contaminated, Buford became ill with typhoid fever, a dangerous disease for anyone, but often fatal for those too worn out to fight it. On November 21, Buford was severely ill and taken to Washington to recuperate. His friend, George Stoneman, took him into his own home to provide the best care. For a time, Buford seemed to improve but soon contracted pneumonia. His wife, Pattie, in Illinois with her family, was urgently called. She quickly made the attempt to travel to Washington. 9

When it became clear that Buford would not survive, General Stoneman approached Abraham Lincoln, asking if the devoted commander could receive a deathbed promotion to the rank of Major General. Lincoln approached Edwin Stanton with the request. Stanton, who distrusted, albeit without merit, the capable Buford, asked if he were dying. When given the affirmative answer, Stanton agreed to the promotion. 10

Buford was awake and lucid when he received the news of his promotion. He was also incredulous. “ Does he mean it

?” Buford asked. When he was told that the promotion was indeed forthcoming, he lay back upon the pillows and sighed. “It is too late,” he said. “I wish I could live now.” 11

Many, many others, wished the same. Sadly, Buford slipped into unconsciousness and died on December 16, 1863, in the home of George Stoneman. One of his staff, Myles Keogh, held Buford in his arms in his last moments. Mrs. Buford had not arrived in time. Ironically, Buford died on Harry Heth’s 38th birthday. 12

The men of Buford’s command were inconsolable. “They loved him like a father

,” one veteran wrote of the man who had led them so capably through so much. 13

After a grand military funeral in Washington, D.C., attended by General Stoneman, President Lincoln, and myriad others, Buford’s remains were carried to West Point, where he was buried. Today, an impressive monument marks his grave, with money supplied for it from the men who served under his command.

On July 1, 1893, another memorial to Buford was erected in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. On the Chambersburg Pike at McPherson’s ridge west of town, a portrait statue of General Buford stands resolutely facing the road toward the oncoming Confederate troops. 14

When John Buford survived Gettysburg, he only had a few more months on earth. Like those who perished on the field, this intrepid commander also gave his life for the nation he loved. Buford completely wore himself out in the service of the United States Army.

He had been the right person in the right place at the right time during the summer of 1863. Had Gettysburg “not been held by us,” recalled one of his men, “history would have had another story to tell.” 15

Sources: John Buford Personal File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Official Report, Buford to Pleasonton, part III, John Buford Personal File, GNMP. Fox, William and Daniel Edgar Sickles. New York at Gettysburg

, Vol. II. Albany, NY: JB Lyon Publisher, 1900. Copy, GNMP. Longacre, Edward. General John Buford: A Military Biography

. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1995. Phipps, Michael and John S. Peterson. “The Devil’s To Pay”: General John Buford, USA

. Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. Shue, Richard S. Morning at Willoughby Run

. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1998. Daniel Skelly File, Personal Accounts, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders

. Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders

. Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

End Notes:

1. Longacre, p. 42.

2. Phipps, p. 19.

3. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 53.

4. Shue, p. 29.

5. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 481.

6. Daniel Skelly File, ACHS.

7. Buford Personal File, GNMP.

8. Buford to Pleasonton, OR, p. 835. Buford Personal File, GNMP.

9. Longacre, p. 244.

10. Ibid., p. 246.

11. Phipps, p. 62. Longacre, p. 247.

12. Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 133.

13. Buford Personal File, GNMP.

14. Fox, p. 1153.

15. Ibid., p. 1154.