Lincoln: Our Most Eloquent President

by Diana Loski

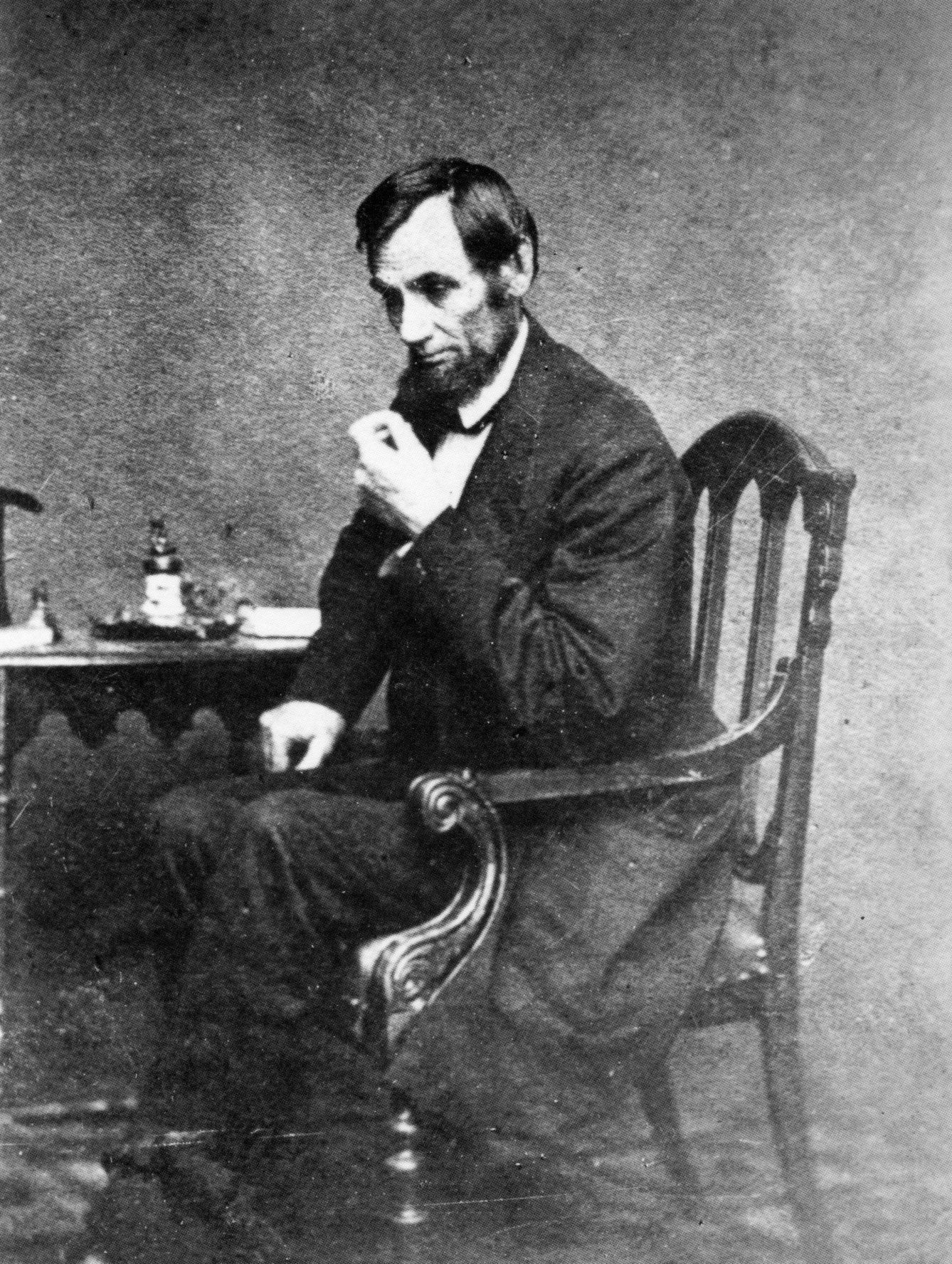

(Library of Congress)

The Gettysburg Address, uttered 157 years ago by our 16th President, was delivered as part of the dedication of America’s first National Cemetery. The high volume of slain from the battle had necessitated it. While Lincoln had asked others, like his Secretary of State William Henry Seward, to take a look at his speech, the words of The Gettysburg Address are classic Lincoln.

Had he not risen to hold America’s highest office, Abraham Lincoln would likely have made his mark on the world by his writing. There was no need for a speech writer in the White House during the Civil War.

Samples from some of Lincoln’s famous speeches demonstrate his amazing aptitude for eloquence.

Throughout his life, Lincoln offered many addresses in defense of the Constitution, which he considered a sacred document. Speaking at a Young Men’s Lyceum in January 1838, he opined against changing the Constitution: “No slight occasion should tempt us to touch it. Better not take the first step, which may lead to a habit of altering it….It can scarcely be made better than it is….The men who made it, have done their work, and have passed away. Who shall improve on what they did

?”1

We can be grateful for Senator Stephen Douglas and his inherent bigotry, which he called “popular sovereignty”, because many of Lincoln’s greatest speeches came from his nationally known debates with the pompous Judge Douglas. One was forever remembered as the “House Divided” speech, given in Springfield, Illinois on June 16, 1858. In part Lincoln said: “ 'A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half-slave and half-free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved – I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”2

Later that fall, in Quincy, Illinois, Lincoln said the following in another debate with Douglas: “That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent. It is the eternal struggle between the two principles…The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same…spirit that says, ‘You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.' No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation, and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.”3

After losing the Senate race to Douglas, Lincoln still gave speeches defending individual freedoms based on the Constitution. At a gathering in Cincinnati, on September 17, 1859, Lincoln again defended liberty and the document that was supposed to provide it by saying, “The people of these United States are the rightful masters of both Congresses and courts, not to overthrow the constitution, but to overthrow the men who pervert the constitution.”4

On February 16, 1860, Lincoln spoke at the Cooper Union Building in New York City. He continued to ardently defend the Constitution and the liberty it promised. It was the speech that ignited the members of the newly formed Republican party to nominate him for the Presidency. He finished with: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” It was this speech that catapulted him toward the highest office in the land.5

Both of Lincoln’s inaugural addresses are masterpieces at reaching the individual within the masses and describing the lofty ideals for a united America that were too often ignored. In the last paragraph of his first inaugural speech, given on March 4, 1861, he pleaded: “We are not enemies but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passions may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” The last sentences of his second inaugural speech are equally poetic, yet easily understood: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”6

Between the two speeches, the nation was divided in the ferocity of relentless war. The struggle wore down the President, who worked tirelessly to keep the Union and put down the rebellion. One of his great speeches in that turbulent time was the lengthy annual message to Congress on December 1, 1862. He summarized with: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country. Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history, we of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We – even we here – hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free – honorably alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last, best hope of earth.”7

Just a month later, true to his word, Lincoln published the Emancipation Proclamation. And later that same year, on November 19, 1863, the President spoke at Gettysburg for just about two minutes. His 271 words, better known as The Gettysburg Address

, ended with the inspirational “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that the government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”8

Lincoln understood that America was the great experiment, and that all other nations were watching us, as our Civil War demonstrated that “eternal struggle between two principles.” They are watching us now.

Lincoln knew that he was only a small part of a deadly but historically pivotal time, yet he was an essential agent during that time. His words reflect his understanding of the role he played. By his simple yet elevated prose, Lincoln was able to impart the eternal nature of his deeply felt national dream to the masses. Over a century and a half later, we still ponder and are amazed at his way with words.

Lincoln's 2nd Inaugural

(Library of Congress)

End Notes:

1. Boritt, p. 94. It is interesting to note that James Madison, the last surviving signer of the Constitution, had died seventeen months earlier, on June 28, 1836.

2. Sandburg, p. 138.

3. Ibid., pp. 141-142.

4. Selected Writings

, p. 567.

5. Ibid., p. 594.

6. Ibid., pp. 624, 727.

7. Ibid., p. 673.

8. Lincoln, The Gettysburg Address,

GNMP.