March 1895: "It is Too Late"

by Diana Loski

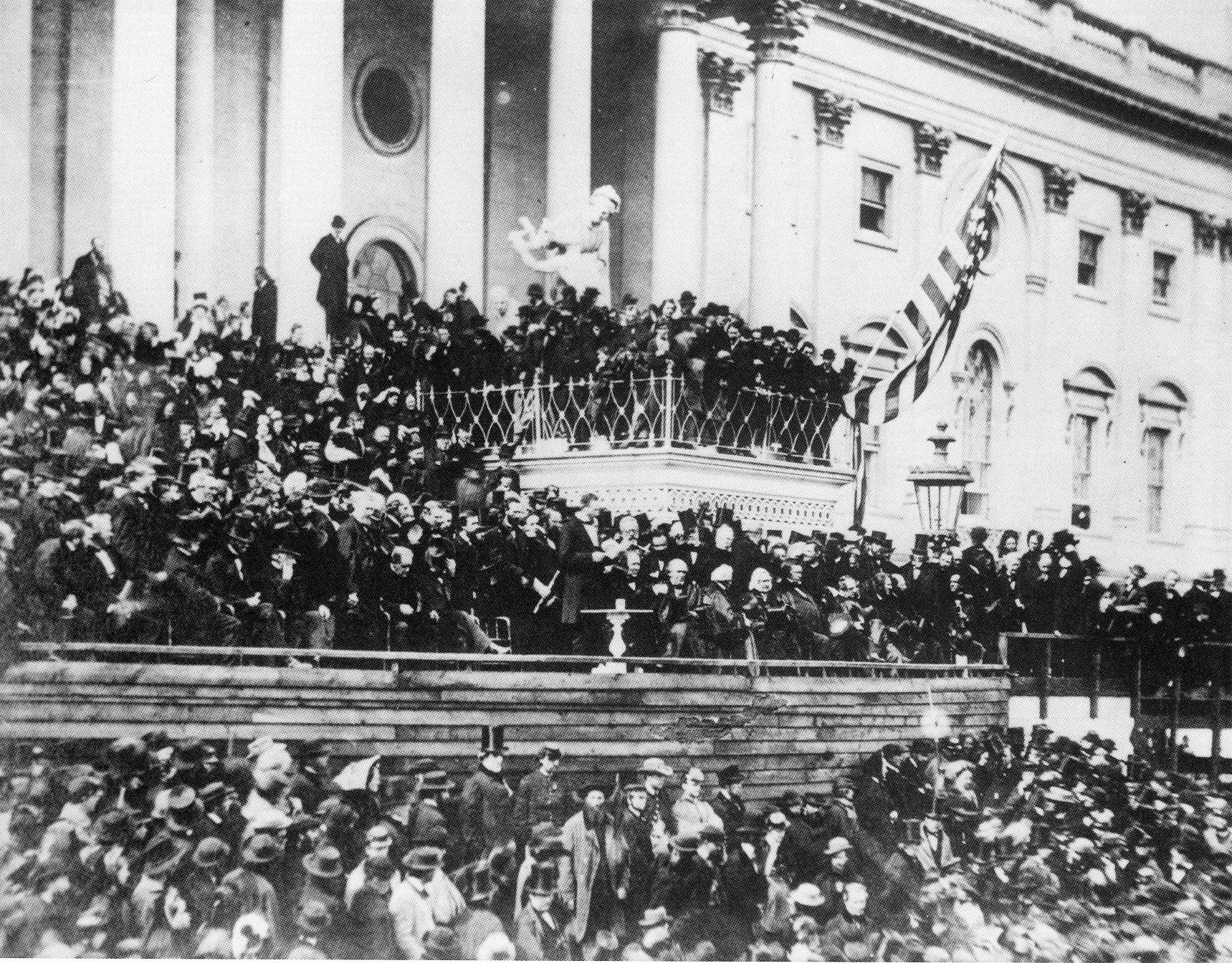

Lincoln's 2nd Inaugural

(Library of Congress)

As a wintry February turned into March in early 1865, the war doggedly continued as the South hung grimly on, hoping a miracle would rescue them from the otherwise certain outcome of losing the war. The Union forces continued to usurp the hopelessly outnumbered Confederate forces, rushing onward like floodwaters of the coming spring, as the men in gray faced unrelenting cold and approaching starvation.

Colonel John Mosby’s Rangers kept up their havoc on the Federals, but General Grant, who led all Union forces, issued an order to “hang them without trial” when any of Mosby’s men were captured. Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer immediately obeyed the order, and dispatched six of the raiders by hanging two and shooting four more.1

“The weather is very bad,” Phil Sheridan wrote to Grant at the beginning of the month. “The spring thaw, with heavy rains” was making travel difficult. It made battle unlikely for the foreseeable future.2

In Virginia, General Lee attempted to unite his generals, including two who had been called back to service. Generals Joseph Johnston and Pierre T. Beauregard had been ousted from commanding any armies due to the petty jealousies of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Lee was aware of their abilities and urged them to rally for the flailing Confederacy. Johnston took over the residue of an army in North Carolina while Beauregard attempted to aid what was left of the Army of Tennessee. Lee expressed to all of his own subordinates that he had “confidence in your ability…and [your] devotion to the cause.” The South was losing the equivalent of about a regiment per day, either to desertion, death, or the fact that starvation rendered them unfit for service.3

In Washington, the weather was equally foul, interfering with Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Ceremony on March 4. The day dawned a dreary gray, and rain poured incessantly throughout the morning. At 11 a.m., the rain stopped, just before the inaugural began. Outgoing Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin gave a farewell address, as incoming Vice-President Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee delegate, had replaced him on the ticket. Hamlin’s gracious address was followed by a strange speech by the new Vice-President, who was obviously intoxicated. Having traveled from Tennessee, with little sleep and understandably nervous, he had unwisely ingested three glasses of whiskey that morning – to obvious and detrimental effect. “That man is certainly deranged,” whispered one of Lincoln’s staff to another. Lincoln kept his head down, staring at the floor until his turn came to speak.4

As Lincoln approached the podium on the Capitol grounds, a sudden burst of sunlight flooded the platform, resting over Lincoln and his podium. Lincoln later said that the sunburst “made my heart jump.”5

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural speech is remembered as one of his greatest oratories. Only his Gettysburg Address equals (or surpasses) it in renown.

In his speech, Lincoln eloquently recognized the approaching end of the war, and set forth a plea to his estranged countrymen to return. He benevolently promised that all would be forgiven: “With malice toward none, with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace.”6

At precisely noon, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase issued the oath of office to Abraham Lincoln.

Among those in the crowd was actor and avowed racist John Wilkes Booth. Away from the stage for several months, Booth had attempted to kidnap the President, and was still insistent to try it at this late date, in order to ransom Lincoln for thousands of Confederates in Union prisons. As Grant had recently agreed upon a prisoner exchange, some of Booth’s compatriots had felt that the kidnap plot was no longer viable. Booth lashed out at their unwillingness, calling them “cowards” and threatened to shoot one of his group, Sam Arnold, who began to suspect Booth of a more sinister plan.7

After the inaugural ceremony, Lincoln welcomed guests at a reception, held at the Executive Mansion. Among those in attendance was Frederick Douglass. Lincoln noticed him on the periphery, as it appeared others were barring his entry. Lincoln called to Douglass, and invited him into the reception. He asked Douglass what he thought of Lincoln’s speech that day. Douglass quietly praised it, calling the speech “a sacred effort.”8

As the relentless cold and rain continued, more Union progress came. General William T. Sherman crossed the border into North Carolina on March 7, threatening Johnston’s army. An alarmed General Lee urged Johnston to prevent Sherman from reaching the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg, the city Lee was desperate to hold. Johnston’s reply was terse and coldly realistic: “It is too late,” he wrote. “In my opinion, these troops form an army too weak to cope with Sherman.”9

Johnston’s army nevertheless met Sherman and his army at the Battle of Bentonville in North Carolina. The battle, fought from March 19 to the 21, resulted in four thousand casualties and a decisive defeat for the South. Johnston quickly retreated, hoping to continue the fight another day. It was, however, Johnston’s last battle of the war.

After his victory at Bentonville, Sherman continued his march northward. While his troops remained in North Carolina, Sherman met Grant at his headquarters near Petersburg. They were joined by President Lincoln, with his wife and son Tad, at City Point. The Lincolns met General Grant aboard the vessel The River Queen. While the end of war was definitely in the air, Lincoln and Grant knew that more fighting was imminent to bring the war to a decisive close.

Lincoln appeared to be in high spirits, but just a few days before his trip into Virginia, Lincoln had been so worn by the stress of the ongoing war that he had fallen ill. Bedridden, he had led a Cabinet meeting in his private quarters, and in pajamas. It wasn’t until March 23 that he felt well enough to board The River Queen and make the journey to City Point.10

Always eager to meet the ranks, Lincoln enjoyed the company of the troops. Among them was a new commander: General Edward Ord of the Army of the James. Mrs. Ord was also in attendance. On Sunday, March 26, Lincoln rode to inspect the troops and Mrs. Ord accompanied him. The act infuriated Mary Lincoln, who reacted by unleashing a jealous outburst. Mrs. Ord was aghast. She had certainly meant no harm and was horrified at Mrs. Lincoln’s violent invective. Through the episode, Lincoln “bore it with an expression of pain and sadness that cut one to the heart.” Mrs. Lincoln retired to her quarters on the riverboat, and remained “indisposed” for the rest of the trip.11

Shortly after the inspection and subsequent tirade, Generals Grant and Sherman determined to return to the front. Lincoln opted to remain at City Point. He was reluctant to go back to Washington with the victory and end of the war so tantalizingly close. As Grant prepared to depart, Lincoln implored him, “My God, my God! Can’t you spare more effusion of blood? We have had so much of it.”12

A few days later, more unfortunate effusion took place as Lincoln watched from The River Queen. He saw a barrage of artillery emit a firestorm of death in the distance, hoping the terrible war would finally stop.13

In Washington, the hate mail and death threats against Lincoln continued to pour in. Lincoln took them in stride, but his associates and close friends were deeply concerned. The only one who believed Lincoln was not in danger was the Secretary of State, William H. Seward. “Assassination is not an American habit,” he claimed.14

In Petersburg, desperation began to rear its head. Lee realized the hopeless situation in the city he had for so long defended against the Federal siege. He decided that the only hope against surrender was to vacate Petersburg and join forces with General Johnston. It meant not only the loss of Petersburg, but Richmond as well.

Once Lee divulged his plan to Jefferson Davis, the Confederate President urged his wife and children to leave Richmond. They reluctantly complied, but one of the couple’s young sons clung to his father and wept as they said goodbye. Davis remained stoic and watched them until they disappeared in the distance. “He thought he was looking his last upon us,” Varina Davis later recalled.15

As March finally gave way to April, Lee’s troops vacated the city of Petersburg. The remnants of Lee’s army, a fraction of what they once were, decided to make a stand at a country junction west of the city known as Five Forks. As Union forces pressed them relentlessly, the battle cost many Confederate lives, resulting in a Union victory. The following day, Petersburg fell to Union forces, and Lincoln prepared to visit the vanquished Confederate capital of Richmond.16

Both the Blue and the Gray then made their way south, fatefully and unrelentingly, toward a place called Appomattox.

Sources: Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. New York: Da Capo Press, 1982 (reprint, first published in 1885). Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus. New York: Random House, 2004. Oates, Stephen. With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln. New York: HarperCollins, 1977. Warner, Margaret E. The Library of Congress Timeline of the Civil War. New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2011.

End Notes:

1. Foote, p. 805.

2. Goodwin, p. 696. Foote, p. 808.

3. Foote, p. 808. Grant, p. 525.

4. Wagner, p. 221. Goodwin, p. 697.

5. Foote, p. 812.

6. Oates, p. 411. Wagner, p. 221. Goodwin, p. 699.

7. Kauffman, pp. 180-181.

8. Goodwin, p 700. Oates, p. 411. Wagner, p. 221.

9. Foote, p. 822.

10. Oates, p. 416.

11. Oates, p. 419. Foote, pp. 846-847.

12. Foote, p. 855.

13. Oates, p. 419.

14. Ibid. p. 416.

15. Grant, p. 528. Foote, p. 863.

16. Grant, p. 532.