Memorial Day in Gettysburg

by Diana Loski

Flags adorn Union graves, Soldiers National Cemetery

(Author photo)

Gettysburg has, for many years, been the ideal place for remembering those who came before us. The historic crossroads town was one of the first to commemorate the fallen, known then as Decoration Day, beginning on May 30, 1868. From the humblest of those among the citizenry to Commanders-in-Chief, millions have cumulatively visited Gettysburg for Memorial Day.

On May 5, 1868, General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic issued General Rule #11:

“The 30th of May, 1868 is designated for the purpose of strewing flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance, no set form or ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services or testimonials of respects as circumstances may permit.”1

And so it began.

On May 30, 1868 in Gettysburg, shops and places of business closed in the late afternoon. A salvo of cannon, fired from Cemetery Hill, announced the beginning of the commemoration. Shortly afterward, a procession formed in the Diamond at the town center, including Civil War veterans, statesmen, and the Gettysburg Brass Band. A group of children, orphans of the Civil War, reverently carried bouquets to lay upon the graves of their fathers in the cemetery. The parade was led by the first Chief Marshal of Memorial Day in Gettysburg, Captain John McCreary.2

The band played the Dead March upon entry to the National Cemetery, greeted by nearly two thousand spectators. The keynote address was given by Reverend James A. Brown, the former chaplain of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry. After the address, the children were permitted to place the flowers on the graves.

Today, Memorial Day in Gettysburg is commemorated in a similar fashion, although it has evolved from past events. Here are some of them:

In 1877, the first non-Gettysburg civilian gave the keynote address in the Soldiers National Cemetery on Decoration Day. He was J.M. Vanderslice of Philadelphia. That same year, as most of the orphans had moved or grown to adulthood, children from Gettysburg schools began strewing the flowers on the soldiers’ graves. That tradition continues.3

That same year, shops closed at 1 p.m., a few hours earlier than originally done. The crowd swelled to 10,000 visitors.

The following year, in 1878, the first sitting U.S. President attended Gettysburg’s Decoration Day commemoration. He was Rutherford B. Hayes, and he had served as a general officer for the Union during the Civil War. That year, the honorable Andrew Curtin, who had served as Pennsylvania's governor during the Civil War, accompanied the President on the dais. While President Hayes was in attendance, he did not give the keynote speech. That honor fell to former Union General Benjamin Butler from Massachusetts.4

In 1874, Memorial Day was declared a national holiday. Banks and government offices closed for the day so that the people could spend the day with their families and participate in the commemorations. With the closure of businesses, the parades and ceremonies could begin earlier, and they did. To this day, the Gettysburg Memorial Day parade begins at noon, followed immediately by the ceremony in the Soldiers National Cemetery.

In 1888, William Ryan from New York recited the Gettysburg Address in the National Cemetery as part of the Memorial Day commemoration. The speech was received “with dramatic effect.” From that time, and for many years, Lincoln’s famous oration was uttered during the commemoration for Memorial Day at the Soldiers National Cemetery.5

That same yar, English soldiers from the Honorable Artillery of London attended Gettysburg’s Memorial Day festivities. The British unit at that time celebrated two hundred years of its existence.6

General Charles Collis, a Civil War veteran who missed the Battle of Gettysburg due to illness in the summer of 1863, had moved to Gettysburg in a home that still stands on Seminary Ridge. In 1901, the new Gettysburg civilian began taking photographs of the school children as they placed the flowers on the soldiers’ graves. Some of those graves contained the mortal remains of the men of his former command. Collis’s Zouaves, the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry, had fought in the Peach Orchard during the battle. Collis’s wish was, at his death, to be buried among them. When he passed on, his request was granted. General Collis is the highest-ranking general to be buried in the National Cemetery. His grave lies among the Pennsylvania slain.7

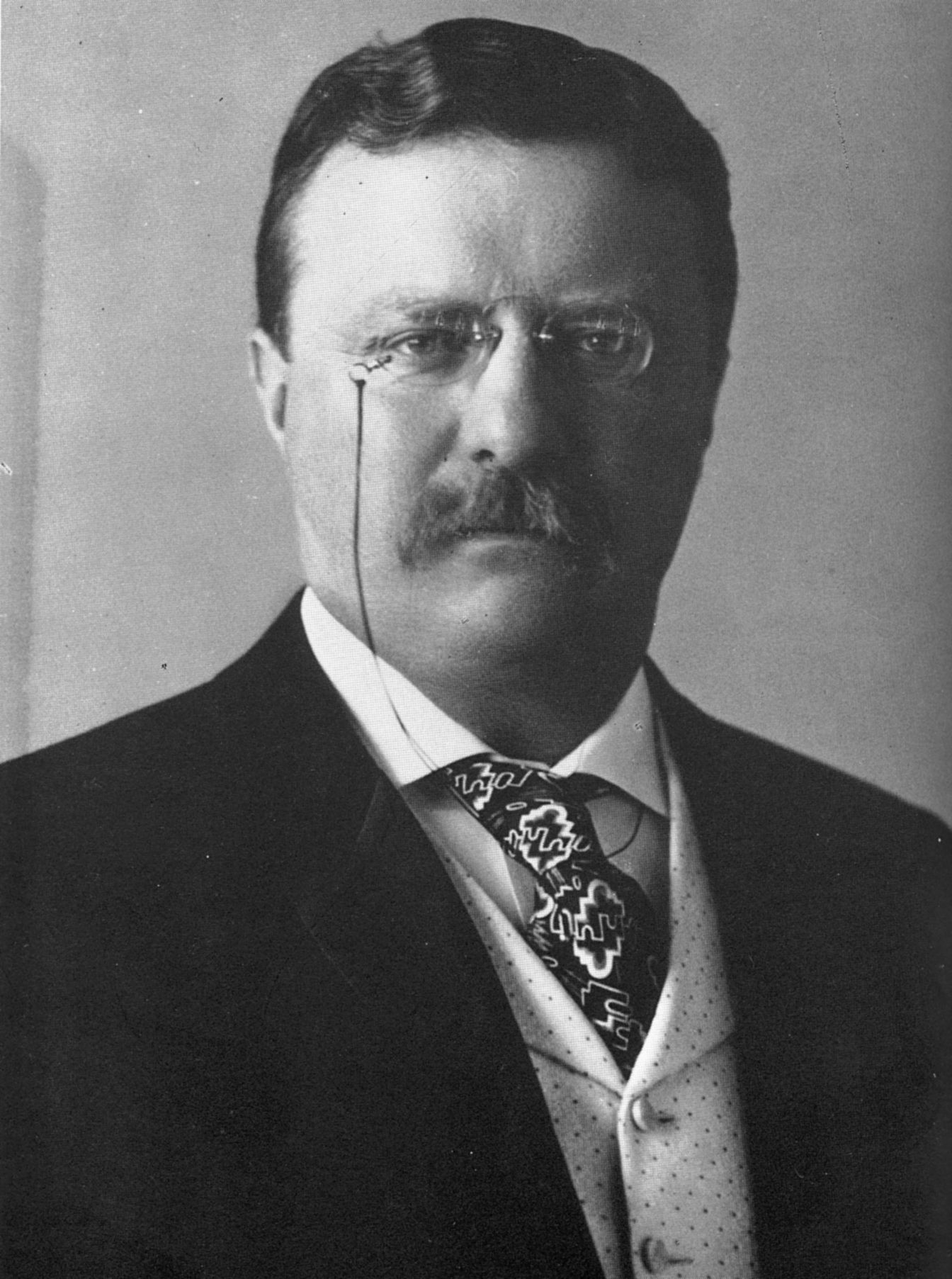

In all, five U.S. Presidents have delivered addresses in the National Cemetery for Memorial Day at Gettysburg. They are: Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Theodore Roosevelt, in 1904, was the first U.S. President since Lincoln to give a speech in Gettysburg’s National Cemetery. Over 20,000 people turned out to see him. Mr. Roosevelt, after completing his tenure as Commander-in-Chief, visited Gettysburg a second time, on May 30, 1912, and gave the keynote address yet again, to great fanfare.

Many Gettysburg veterans and sons of veterans served as Chief Marshals of the Memorial Day commemorations at Gettysburg. Among them was Civil War veteran Theodore McAllister, who presided over the event in 1888, 1891, 1893, and 1907. In 1894, though he was not the keynote speaker, McAllister gave an address in the cemetery for the occasion. Another leading participant was Captain Henry Stewart, the son of Gettysburg teacher and diarist Salome Myers Stewart. He served for many years as Chief Marshal, until ill health prevented him in the early 1920s. Captain Stewart also served for many years as the presiding officer of the Corporal Skelly post of the local GAR (Grand Army of the Republic – a Union veteran organization).

In 1880, Congressman Charles Williams of Wisconsin visited Gettysburg and aptly described the reason for Memorial Day: “This is sacred ground, and few places on earth possess a more enduring fame. Though annual, the commemoration of the bravery of the dead here buried can never grow old.”8

The Honorable Henry Hull, in 1901, echoed the same sentiment, with a profound comparison: “There is a …question of cost, one which no arithmetic can compute, whose sum is one of the secrets of eternity. Who can number the mother’s tears, the widow’s cries, the orphan’s lamentations? Who can count the heart throbs, the weary days, the sleepless nights, the anguish of those who watched and waited for loved ones who never returned?...The greatest cost of war…is the cost of human suffering and human life.”9

The veteran has, since the inception of the nation, been regarded with honor as the protector of liberty. The survivors of war have, at war’s end, continued their lives – some with great achievement. That gift was denied the slain of war. “We reflect upon what those who died might have done and accomplished,” remembered Henry Hull, “had the opportunity been theirs.” One of the sad facts of history is that we will never know the answer to that question.10

The bravest and best were almost always the ones who never came back.

Thousands have remained here, in the fertile Pennsylvania soil, at the crossroads town of Gettysburg. While their dreams and hopes were buried with them, those who stand by their final resting places on Memorial Day remember them with eternal gratitude, as our dreams continue, an extension of what was once theirs so many years ago.

Theodore Roosevelt

(Library of Congress)

Sources: The Memorial Day General Information File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). The Gettysburg Star & Sentinel, May 27, 1868. The Gettysburg Compiler, June 3, 1877. The Gettysburg Star & Sentinel, June 1, 1897. Historical newspapers accessed through newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. The Gettysburg Star & Sentinel, May 27, 1868.

2. The Gettysburg Compiler, June 3, 1877.

3. Ibid.

4. The Memorial Day General Information File, ACHS.

5. The Gettysburg Star & Sentinel, June 1, 1897.

6. Ibid.

7. Memorial Day. General Information File, ACHS.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.