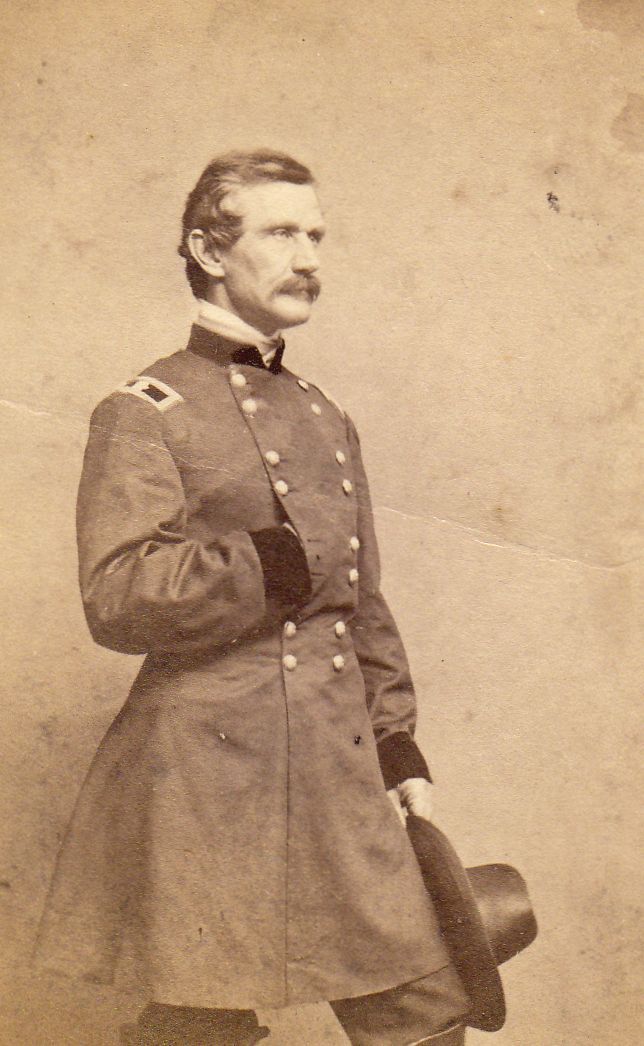

General A.A. Humphreys

"The Great Soldier of the Army of the Potomac"

by Diana Loski

General A.A. Humphreys

(National Archives)

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys was born to be a soldier. He was the third child and second son of Samuel and Letitia Atkinson Humphreys of Philadelphia, coming into the world on November 2, 1810. He was “a sympathetic child”, according to his mother, to whom he was particularly close. He was of average height, “steely” blue eyes and brown hair. From a young age, he displayed a “total disregard for danger.” The family was wealthy and prominent: his paternal grandfather, Joshua Humphreys, was known as the Father of the U.S. Navy. Andrew’s father had naturally pursued the same naval and engineering traits, and the young Humphreys also followed this genetic path, albeit for the army instead of the navy.1

Graduating from West Point in 1831, Humphreys began his nearly half-century of duty to the Federal army with the artillery, and later with the engineers. A topographical engineer, he worked from Florida to Cape Cod to the west, building lighthouses, levees, and aiding in the construction and improvement of various fortifications. He participated in fighting the Seminole uprisings in Florida in the middle of the 1830s, and fell so ill with yellow fever that it almost proved fatal. He had to resign his commission for two years, working during that time as a civil engineer in Washington. Once his health had improved, he again received a military commission, conducting surveys on the Mississippi River and planning the construction of the railroad to the western territories. He married Rebecca Hollingsworth, a Philadelphia socialite, on June 19, 1839. Four children were born to the couple: Henry, Charles, Rebecca, and Letitia.2

Humphreys served during the Pierce and Buchanan administrations, often appearing before Congress with maps, profiles, and information pertaining to costs for the various engineering projects with the building of national railroads. War interrupted Humphreys’s survey work in Washington. He offered his services to the Union and was placed on the staff of General McClellan in 1861. During this time, he labored on the defenses of Washington as McClellan’s Chief Engineer. He was transferred to the infantry, receiving his brigadier’s star on April 28, 1862. He then commanded a division in the Federal V Corps in the Army of the Potomac.

Humphreys participated in the Battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. In spite of his abilities, his rise in rank was slow. Because of his engineering intellect and his exactness with duty, he was not popular with subordinates. In his early fifties by 1863, he wore spectacles and earned the nicknames “Old Goggle Eyes” and “the Preacher”. In spite of his Quaker upbringing, Humphreys swore abundantly. He “ was one of the loudest swearers ” and used “distinguished and brilliant profanity.” Yet, his true soldier’s soul was ever present, as exemplified in a letter he wrote after the Battle of Fredericksburg, describing the Union assault upon Marye’s Heights: “I felt gloriously, and as the storm of bullets whistled around me, and as the shells and shrapnel burst close to me in every direction, scattering with hissing sound their fragments…the excitement grew more glorious still. Oh, it was sublime!”4

After the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863, both Hooker’s and Lee’s armies underwent changes due to the losses and resignations of high tier commanders on both sides. Humphreys was reassigned to command a division in the Federal III Corps, led by the politician-turned-general Dan Sickles. Humphreys was not an aficionado of Sickles due to Sickles’s amoral attributes and his lack of military prowess, but he obediently accepted the change.

It would come to a head at the Battle of Gettysburg.

When General Lee’s army headed north into Pennsylvania in June 1863, the Army of the Potomac followed in quick pursuit. The Federal III Corps arrived in Gettysburg late on July 1, after the first day’s fighting had ended. Marching through Emmitsburg, Maryland, and traversing a country road through Fairfield, Humphreys and his division reached the Black Horse Tavern on the Fairfield Road under a brilliant full moon.5

Humphreys, a man of distinct military prowess, instinctively assessed that the Confederates had to be close. In spite of orders from Sickles to keep marching, Humphreys insisted that they carefully check their position. Learning from a disabled Union soldier at the tavern that Confederate pickets were just two hundred yards distant, Humphreys ordered his division to turn about and march as surreptitiously as possible to the other side of Marsh Creek. They did so “ in majestic silence.” Entering Gettysburg and reaching the Emmitsburg Road, the exhausted division lay on the ground between Cemetery and Seminary Ridges, and slept.6

Humphreys’s Division consisted of three brigades. The first, commanded by Brigadier General Joseph Carr, consisted of the 1st, 11th and 16th Massachusetts regiments, the 12th New Hampshire, the 11th New Jersey, and the 26th Pennsylvania. The second brigade, commanded by Colonel William R. Brewster, was filled with all New York regiments: the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd, 74th, and 120th Infantries. The third, led by Colonel George Burling, consisted of the 2nd New Hampshire, the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th New Jersey regiments, and the 115th Pennsylvania Infantry.

When Humphreys’s troops awoke in the morning, they were ordered to their new position on the other side of the road.

While at times a commander who lacks a West Point education might cleverly think outside the box and bring an astounding victory, most of the time a general of high rank who is not familiar with military protocol courts disaster. The latter was the case with Dan Sickles, who disliked the new commander of the army, General George Meade, and felt he did not need to obey his orders. Like Sickles, Meade arrived early in the morning of July 2 and was pleased with the line occupied by his army. With flanks on hills and the middle position on Cemetery Ridge, the interior line, resembling a fishhook, was a good position. Knowing General Lee would need to attack him, Meade ordered the troops to remain in their defensive positions.

One portion of the line was in a swale between Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top. Sickles’s Third Corps, ordered to deploy to the left of the Second Corps, did not like the area. Looking to the west toward the Emmitsburg Road, Sickles saw a rise in the ground by the Peach Orchard. He ordered his troops there, leaving a brigade in Devil’s Den and another in the Wheatfield. The brigades deployed there were part of David Birney’s Division.

Humphreys immediately disliked the order and repositioning, but as a West Point graduate, he obeyed Sickles, as it was his duty.

When General Longstreet saw the portion of the Union line deployed in the Peach Orchard, with Birney’s two Union brigades not supported in the Wheatfield and Devil’s Den, he immediately ordered an attack. At about the same time, General Meade was alerted that the Union left flank at Little Round Top was devoid of fighting troops. It was an alarming situation, and Meade immediately rode to the Peach Orchard to order Sickles to return to the line. The Confederate attack, though, had commenced; it was too late to withdraw.

General Lafayette McLaws’s Division attacked the Peach Orchard, with his Mississippi brigade under the command of General William Barksdale hurling themselves against the Union defenders. Though many of the Third Corps broke and began to run, Humphreys rallied his division, and sent them back to the front, where they stubbornly held their ground. Humphreys was aghast when one of his brigades, led by Colonel Burling, was abruptly taken from them to aid General DeTrobriand in the Wheatfield. Later, Humphreys wrote, “Had my Division been left intact, I should have driven the enemy back, but this ruinous habit…of putting troops in position & then drawing off its reserves & second line to help others, who, if similarly disposed, would need no help, is disgusting.” He wrote that his division lost two thousand men, seemingly needlessly. He later added, “It incenses me to think of it.”7

With one third of his troops taken from him, against terrible odds and in a place where the height was not at all advantageous, Humphreys maintained their position until ordered to withdraw, which he did slowly and with a cool demeanor. As shells burst and bullets zipped around him, Humphreys showed no alarm. He walked calmly among the soldiers, who lay prone in the orchard to escape the shells, and gave direction. As the noise of battle escalated, soldiers remembered his voice “ when roused [was] like a salvo of artillery. ”His temerity helped those under his command to remain equally tenacious. Humphreys maintained that had the troops engaged on the Union left that day remained intact, the result would have been different. In spite of his sterling leadership that day, his losses, which were cataclysmic, left him incensed. “My disappointments,” he wrote, “my mortification at seeing men over me and commanding me who should have been far below me has destroyed all my enthusiasm and I am indifferent. I care no longer for rank and command.” 8

General Sickles was severely wounded near the Trostle Barn that day, ending his military career. That evening, Meade held a council of war at his headquarters, and Humphreys was in attendance. He liked Meade’s forthright manner and agreed that the army should remain at Gettysburg and fight the following day. He later praised Meade by saying, “I don’t know that anyone has an idea of the vast labor connected with the movement of a great Army…this army has never been moved so skillfully before as it has been during Meade’s command.”9

Due to Sickles’s disruptive leadership style, the disaster that befell his corps on the second day at Gettysburg caused such heavy casualties that the Third Corps ceased to exist.

Without the leadership of General Humphreys, the casualty list would have been much higher. He “displayed such resolution and bravery,” one veteran wrote, “that he attracted the attention and won the commendation of his superior officers.” Another remembered that the general showed “ great valor and military skill in handling his division at Gettysburg.”10

General Meade was duly impressed by Humphreys. At the close of the Battle of Gettysburg, he requested that Humphreys become his Chief of Staff. Humphreys replaced the wounded Daniel Butterfield, a close friend of Sickles and Hooker, whom Humphreys considered “false, treacherous, and cowardly.”11

After Gettysburg, Sickles launched into a tirade in the newspapers, insisting, under the pseudonym of Historicus, that George Meade was an inept leader and demanding that Meade lose his command.

Humphreys retained the middle ground in the political fracas, but other generals rushed to Meade’s aid. When Humphreys read a retort by one of them, he wrote to his wife that he “felt a pleasurable sensation” at the reply in The New York Herald.12

General Humphreys remained on General Meade’s staff for the following year, through the Mine Run and Overland Campaigns of 1864. He returned to field command after General Hancock, in November 1864, had to retire his leading the Federal Second Corps due to the severe nature of his Gettysburg wound that remained dangerous a year later. Humphreys commanded the Second Corps until the end of the war, receiving brevets for “gallantry and meritorious conduct” from the battles of Gettysburg in 1863 and Sailor’s Creek in February 1865. He was present at Appomattox Court House when General Lee surrendered his army, hastening the end of the war.13

Humphreys returned to his family and remained a Brigadier General in the post-war army. He continued his work as the Chief of Engineers for the Federal government from 1866 until his retirement in 1879. From the 1830s to the 1870s, Humphreys had been engaged in over 70 battles in his forty-eight years with the army. With his children grown and living comfortably after the Civil War, Humphreys revisited his many philosophical and engineering endeavors. He was a member of the American Philosophical Society, the Hungarian Society of Engineers, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, the Italian Geographical Society, the Geographical Society of Paris, the Austrian Society of Engineers, and the Maryland Historical Society. He spent his retirement writing From Gettysburg to the Rapidan and The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65 . He also wrote a volume for Campaigns of the Civil War .14

He was revered during and after the war as “one of the ablest soldiers of the Army of the Potomac”. He attended reunions and spoke at various veteran functions in Washington, where he and his wife maintained a residence on Connecticut Avenue.15

At Christmastime 1883, the general began to complain of a general discomfort in his chest, as well as the chronic lumbago that he frequently suffered in his back. On Thursday, December 27, he sat reading in his chair by the fireplace. To dispel the winter chill that evening, a female servant stoked the fire and spoke with Humphreys as he read. She claimed he was cheerful. Mrs. Humphreys retired for the evening at 10 p.m. When the general had not retired by 11 p.m. as was his habit, his wife, concerned that something was amiss, asked the maid to check on her husband. When the servant did so, he found General Humphreys still in his chair, dead. He had suffered a heart attack and had died instantly.16

The funeral took place on New Year’s Eve, with the general’s body lying in state at his home on Connecticut Avenue. In accordance with the wishes of the family there was no military display”. Some survivors of his old command attended. Pall bearers included General Horatio Wright, General Henry Hunt, Admiral Alex Murray and the Honorable Theodore Lyman, a Congressman who had also served on Meade’s staff during the Civil War. Secretary of War M.W. Corcoran and Robert Lincoln also attended the funeral. Humphreys was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington.17

“General Humphreys’ name is indissolubly connected with the achievement of a great army” wrote one mourner. He was “a worthy chief” remembered another. Civil War veteran Charles A. Dana perhaps offered the greatest compliment. He claimed that General Humphreys was “the great soldier of the Army of the Potomac.” 18

At Gettysburg, a memorial for the intrepid commander stands, near the spot where Humphreys led his men on July 2, 1863. It can be found just beyond the junction of Sickles Avenue and the Emmitsburg Road. There is another fitting memorial for the mighty warrior that stands farther west, in the state of Arizona. Just north of Flagstaff are three volcanic peaks called the San Francisco Peaks. The highest of the three, located between the others, is Humphreys Peak, the tallest mountain in Arizona. It was named in 1870, when the general was still working for his country, in spite of his grayed hair and faltering heart. For one, like so many, who gave so much for future generations, it remains high, and much deserved, praise indeed.19

The General Humphreys portrait statue, Gettysburg

(Author Photo)

Sources: Biographies of Notable Americans, vol. 5. Salt Lake, UT: Ancestry.com. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. The New York Times, 29 December, 1883. Humphreys, Henry H. Andrew Atkinson Humphreys: A Biography . Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Company, 1924 (Reprinted 1988). The Humphreys Portrait Statue Memorial, Gettysburg. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. The Philadelphia Times, 29 December, 1883. The Rutland Daily Herald, 31 December, 1883. The San Francisco Examiner, 28 December, 1883. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Website: A. A. Humphreys. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1992 (reprint, first published in 1964). The Washington Post, 30 December, 1883. All historic newspapers accessed through newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Warner, p. 240. Humphreys, 25.

2. Biography of Notable Americans

, p. 426. Humphreys, p. 5.

3. Humphreys, p. 147.

4. US Army Corps of Engineers Website: A.A. Humphreys. Pfanz, pp. 135-136. Humphreys, pp. 197, 179. George Meade was also called “Goggle Eyes”, due to his appearance, especially when roused.

5. Pfanz, pp. 44-45.

6. Ibid.

7. Coddington, p. 399. Humphreys Portrait Statue, Gettysburg. Humphreys, p. 202.

8. Pfanz, p. 359. Coddington, p. 356. Humphreys, pp. 202, 324. General Humphreys specifically alluded to Sickles and Birney in his recriminations.

9. Coddington, p. 225.

10. The New York Times, 29 Dec., 1883.

11. Coddington, p. 219. Many others shared Humphreys’ view of Butterfield.

12. Pfanz, p. 517.

13. Warner, p. 241. The brevet for Gettysburg was a brigadier general’s brevet, and for Sailor’s Creek, a brevet for major general. He therefore ended the war as a major-general.

14. San Francisco Examiner, 28 Dec., 1883. The Rutland Daily Herald, 31 Dec., 1883.

15. The Rutland Daily Herald, 31 Dec., 1883. The Washington Post, 30 Dec., 1883.

16. Humphreys, p. 325. The San Francisco Examiner, 28 Dec., 1883.

17. The Washington Post, 30 Dec., 1883. Generals Wright and Hunt, and Congressman Lyman were also veterans of Gettysburg.

18. The Philadelphia Times, 29 Dec., 1883. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Website: A.A. Humphreys.

19. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Webite: A.A. Humphreys. There is also a monument to General Humphreys at the Fredericksburg battlefield in Virginia.