Colonel Henry Morrow:

Courage & Compassion at Gettysburg

by Diana Loski

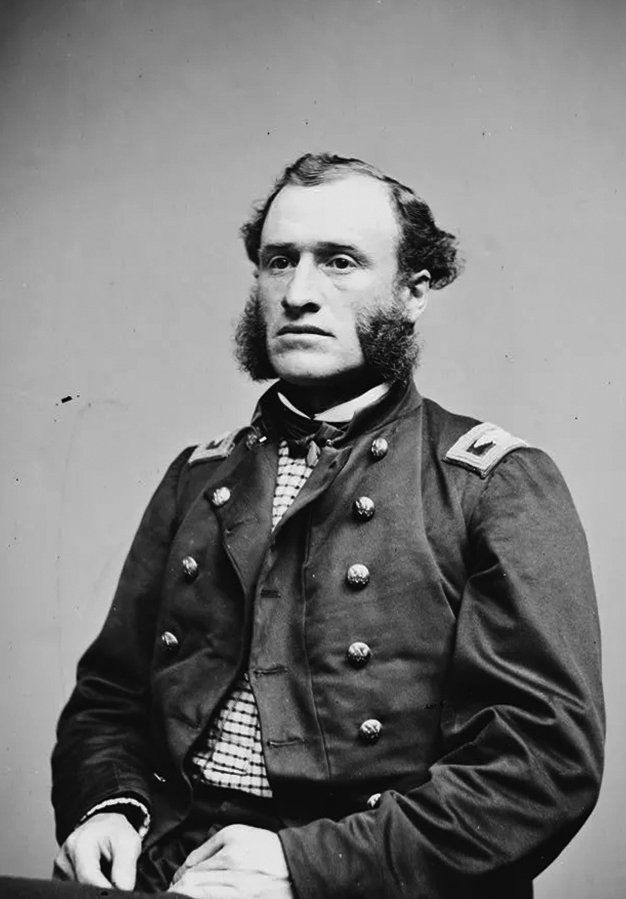

Colonel Henry A. Morrow

(Library of Congress)

The Union’s Iron Brigade has gained eternal fame in the pages of history, especially for their courage and sacrifice at Gettysburg. Of the five regiments in the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the First Corps, the newest was the 24th Michigan Infantry. Raised in the summer of 1862 in response to Lincoln’s renewed call for troops, the Wolverine Regiment proved their mettle with the rest of the men who wore the black Hardee hats. Their commander, Colonel Henry Morrow, was the epitome of a great leader. Not only would he prove his bravery along with the rest of the men in Herbst Woods on Gettysburg’s first day, he would use that courage with equal compassion to save numerous lives in a great act of kindness.

Henry Andrew Morrow was born in Warrenton, Virginia on July 10, 1829. After his education at Rittenhouse Academy in Washington, D.C., at age 17, he joined the U.S. Army and fought in the War with Mexico. At the conclusion of his services, he secured work as a page in the U.S. Senate, where he struck up a friendship with the renowned Michigan senator, Lewis Cass.1

Morrow was without family and Senator Cass took an interest in the young man’s welfare. He advised Morrow to move to Michigan, which Morrow did in 1851. He pursued a law degree and Cass used his connections to get the veteran employment with the court.2

By 1859, Morrow was the judge of the Recorder’s Court in Detroit. He courted and married Isabella Graves, the daughter of Michigan’s Secretary of State, in December 1860. Within a few months of the marriage, the couple learned they were expecting a child. Perhaps the thought of leaving a pregnant wife kept Henry from enlisting when the Civil War erupted in the spring of 1861; perhaps it was due to the fact that Michigan was the frontier and the war was expected to last only a few months. Whatever the reason, after the birth of their son, Robert, in December that year, Henry began to consider joining the fight.3

When President Lincoln called for additional volunteers in late June of 1862, Henry Morrow was determined to answer. He worked to raise a regiment, with the result being the 24th Michigan Volunteers by early August of that year. The regiment comprised a sizable number of family units of fathers and sons – and 135 brothers. The new regiment elected Morrow as their commander.4

The 24th Michigan became the new addition to the already famous Iron Brigade. Morrow keenly felt that the veterans considered his regiment unproven and inferior. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, the first fight for the 24th, the December conflict coincided with Morrow’s young son’s first birthday. He focused on military exactness with his troops as they crossed the Rappahannock amid Confederate sniper fire. “Steady, men,” he shouted to the still green soldiers, “those Wisconsin men are watching you!” The 24th was not heavily engaged at Fredericksburg, and did not receive their Hardee hats until after the Battle of Chancellorsville.5

All would change, and drastically, with the Battle of Gettysburg.

The 24th Michigan and the rest of the Iron Brigade marched in excessive heat and deprivation from northern Virginia to Gettysburg, arriving in the morning of July 1. Their illustrious First Corps commander, General John Reynolds, rushed them to the west of town, having the men tear down fences that interrupted the pace. The fearless general rode with the 2nd Wisconsin, the rest of the brigade following, toward Herbst Woods on McPherson’s Ridge, about a quarter of a mile west of the Lutheran Seminary. Reynolds was killed within minutes of arrival.

The Confederate troops, which turned out to be Archer’s Brigade, were already thick in the woods. Morrow and his men, among the last of the brigade to reach the woods, were also the largest at about 765 men and officers. Having had no time to load their rifles, Morrow stopped them on the crest to allow them to do so, but was ordered toward the woods by one of General Meredith’s staff. Archer’s men were surprised at the arrival of such a large number of men in blue, especially sporting the tall black hats with medallion and black feather, making them appear even taller. “T’aint no militia!” one rebel soldier was heard to say, “it’s the Army of the Potomac!” The Confederates, part of General Heth’s Division, were unpleasantly surprised.6

Four regiments of the brigade -- the 2nd and 7th Wisconsin, the 19th Indiana, and the 24th Michigan -- all worked as a vise to push and surround a large portion of Archer’s men, rushing across Willoughby Run to do so. A Wisconsin soldier captured General Archer, a true coup for the Union. Round One had given them a good return, but the afternoon would cost them dearly.7

After a couple of hours, from noon to about 2 p.m., there was a lag in the fight. Both the Union and Confederate troops were still arriving, and the battle had not been planned by either army commander. In the Civil War, most often the Federals outnumbered the men in gray, but this was not the case on Gettysburg’s first day. By the afternoon, Confederate reinforcements arrived; the Union men facing them on the west of town not only had no reinforcements, they had lost their capable corps commander. It was a disastrous mixture for the Iron Brigade.

On the afternoon of July 1, the Iron Brigade, with the exception of the 6th Wisconsin Regiment who were sent to the unfinished railroad cut, remained stalwart in Herbst Woods. The 24th Michigan occupied the most difficult of positions: they were at the center of the line, which was curved outward and facing the wrath of the approaching reinforcements. Pettigrew’s North Carolina Brigade advanced, screaming and firing as they appeared. They were supported by Brockenbrough’s Virginians and the remnants of Archer’s men. They vastly outnumbered the men with the black hats. Colonel Morrow attempted to receive permission to move back behind some brush and breastworks for cover, but brigade commander General Meredith, taking orders from Abner Doubleday (the new commander in place of the fallen Reynolds), refused it. The largest of the Iron Brigade regiments soon saw their numbers dwindle. According to one survivor, they “ were shamefully ordered to stand there without support of either troops or cannon.”8

The 19th Indiana, which formed the left flank in the woods, finally gave way and the Confederates pushed toward the men from Michigan in a furious sweep. Morrow saw that they had to retreat, and they carefully, step by step and in good order, did so, firing as they went. So many color bearers fell that Morrow for a few minutes took the colors: “I now took the flag,” he reported, “from the ground where it had fallen, and was rallying the remnant of my regiment, when Private William Kelly of Company E took the colors from my hands, remarking as he did so, ‘The Colonel of the Twenty-Fourth shall never carry the flag

while

I’m alive.’ He was killed instantly. Private Lilburn A. Spaulding of Company K seized the colors and bore them for a time.” 9

Shortly before reaching the fence near the Seminary, Morrow was shot in the head. Unable to see with the blood flowing and walking with difficulty, an aide placed Morrow on a horse and sent him to the rear.10

The 24th Michigan Memorial, Gettysburg

(Author photo)

The wounded Colonel Morrow reached the house of Mary McAllister, a civilian who lived on Chambersburg Street across from the Seminary chapel. She offered to hide him, but he refused, saying he did not wish to endanger the family. When other Union soldiers attempted to hide, Morrow would not allow it. Soon enough, Confederates entered the house, exclaiming, “Look at the birds!” and took Morrow and the other Union soldiers. Mary McAllister, upon Morrow’s request, took his diary and hid it in her skirt.11

Captured, Colonel Morrow was examined by a Confederate surgeon, who told an officer of the 15th Virginia Cavalry that the colonel would likely not survive his wound. Since Lee’s men had overtaken the town, Morrow was set at liberty, and went to the house of Gettysburg attorney and judge David Wills, where he was given medical attention and a place to sleep. Jennie Wills, the wife of Judge Wills, took interest in the ailing officer, and after a day of her skillful nursing, Morrow felt better. Anxious to learn how the Union was faring, he “climbed the steeple of the Court House” and watched Pickett’s Charge on the afternoon of July 3. His feelings were “ strong and painful

” as he saw the charge, concerned that the South would be victorious. “At first he thought all was lost,” but saw the changing of the Confederate tide when the men of the Union rose and repulsed it. While in the tower, a shell exploded near him, but “he kept at his post until the battle was over.”12

After the charge, Morrow returned to the Wills House. On the way, he heard from passing Confederates that many Union wounded were still left on the fields to the west of town. Morrow instantly knew that those left behind were his men, and he quickly found his way to the headquarters of General John Gordon with his concerns. General Gordon, thinking that Colonel Morrow was a surgeon, immediately chided his staff, saying, “Is this so, and if so, why is it?” One of the surgeons in gray explained that they had not been able to get the wounded from the extreme areas of the battlefield. Gordon promptly sent twelve wagons to help secure the wounded from the first day’s fight.13

As the colonel left the Wills House in his errand of mercy, the mistress of the house extended to him a mercy of her own. “Mrs. Wills declared the Colonel would be unsafe in the midst of Confederates without [being] protected in some way.” She took a green scarf -- the sign of a surgeon -- and tied it around his right shoulder.14

As night fell, Colonel Morrow began what was his supernal act at Gettysburg. All night long, he searched the woods, creek, and fields for surviving wounded. The dead surrounded him, many bloated and blackened beyond description. He “heard the cries of wounded men,” and exclaimed later that “it is too painful to dwell upon.” Once the wagons were full, he escorted them to homes and other places of shelter. He then returned to the grim task, until he was satisfied that he had found all the surviving wounded from both sides. They had been struck down and left in the heat without food or water for three days.15

Once the Confederate retreat had occurred and the Union followed suit, Henry Morrow was able to accompany the troops. He stopped at the McAllister home on his way out of town. Mary McAllister did not recognize him. “Why, Miss Mary,” the colonel exclaimed, “don’t you know me?” She replied that he looked like Colonel Morrow, “but he was captured.” Morrow smiled and insisted that it was indeed he; Mary gladly welcomed him, and returned his diary.16

Because of the terrible battle at Gettysburg, the Iron Brigade was greatly reduced in numbers. Though Morrow and the other survivors returned to the ranks and fought until the end of the war, the new recruits, many of them from Pennsylvania, were not the frontier fighters that the Black Hats had been.

Morrow was twice more wounded in 1864: at the Battle of the Wilderness and at Petersburg. In early 1865, the 24th Michigan was sent to Illinois, notably the town of Springfield, for recruiting purposes. As a result, they missed Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.17

The 24th, however, had one more service to render. When the body of the slain President was returned to Springfield for burial, the 24th Michigan served as the honor guard at Lincoln’s final memorial service. Finally, in July 1865, Colonel Morrow was honorably discharged and returned home to Michigan.18

After the war, Colonel Morrow and his wife had three more children: Frank James, Malcolm, and Isabel. Rather than return to law or the courts, Morrow remained in the army. He was brevetted with a brigadier’s star after the war, and maintained the rank of Colonel with the regular army, serving for years helping with Reconstruction, then leading the 21st Infantry. He and his family lived in many post-war places, from the South to Vancouver, Washington, and Nebraska.19

Shortly before his sixtieth birthday, Henry Morrow fell ill. He was diagnosed with “a fatal illness

”, but persevered with his army tasks. In September 1890, he wrote a letter to Colonel Edwards, his second in command at Gettysburg. He wrote, “I have just returned from the G.A.R. encampment, where I had a pleasant time, but you know I am all shattered in health. At present I cannot speak above a whisper. I do not pretend to give commands on the field.”20

On January 31, 1891, Colonel Morrow breathed his last while on duty in Hot Springs, Arkansas. His widow took his remains to her hometown of Niles, Michigan for burial. Many of the survivors of the 24th Michigan – some of whom were rescued by the colonel at Gettysburg – hurried to attend his funeral. And through all the long intermediate struggle,” one reporter wrote in remembrance, “he kept ever in view his high standard of manhood and did always the chivalrous act.”21

He was buried with military honors in Silver Brook Cemetery on a cold winter’s day. “He has reached his last camp ground,” said one of his old comrades from Gettysburg.22

Of all his chivalry, the one that stands high above the rest was his all-night vigil at Gettysburg, where, still wounded and not healed, he hurried in the darkness to save not only his men, but any sufferer left on the field. And through it all, he gave credit to General Gordon, exulting his “humane treatment” that “saved numerous lives.” In the years that followed, Morrow remembered the ones who never returned. “Of the killed,” he wrote, “nothing less can be said than that their conduct in this memorable battle was brave and daring.”23

Henry Morrow, in war or times of peace, continued to always think of the men he commanded – which he demonstrated in his compassionate act on the fields of darkness at Gettysburg.

Sources: 24th Michigan Memorial, Gettysburg PA. 24th Michigan Official Report (prepared by Col. Morrow), Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Copy, stonesentinels.com. Curtis, O.B. History of the Twenty-Fourth Michigan of the Iron Brigade . Detroit: Winn & Hammond, 1891. Copy, GNMP. Detroit Free Press, 6 February, 1891. Encyclopedia of American Biography . Vol. I, Washington, D.C.: American Historical Society, 1934. Copy, GNMP. Haddon, R. Lee. “The Deadly Embrace: The Meeting of the Twenty-Fourth Regiment Michigan Infantry and the Twenty-Sixth Regiment of North Carolina Troops”. Gettysburg Magazine, no. 5, July 1991. Herdegen, Lance J. Those Damned Black Hats! The Iron Brigade and the Gettysburg Campaign . New York & California: Savas Beatie, 2008. Mary McAllister Civilian Account, Civilian Accounts File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). “Colonel Morrow’s Report”, Iron Brigade File, GNMP. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day . Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

End Notes:

1. Encyclopedia of American Biography, pp. 408-9.

2. Ibid.

3. Hadden, p. 19. Detroit Free Press, 6 Feb. 1891.

4. Ibid.

5. Herdegen, p. 59.

6. 24th Michigan Memorial, GNMP.

7. Pfanz, p. 100.

8. Hadden, p. 27. Pfanz, p. 277.

9. OR, 24th Michigan, GNMP.

10. Pfanz, pp. 288-289.

11. McAllister File, ACHS.

12. “Colonel Morrow’s Report”, pp. 53-54. The place where the colonel watched Pickett’s Charge may not have been the Court House, as the report stated. Other sources (Pfanz and Herdegen) attest it was in the steeple of a church.

13. “Colonel Morrow’s Report”, pp. 54-55. Herdegen, p. 193.

14. “Colonel Morrow’s Report”, p. 55.

15. Ibid.

16. McAllister File, ACHS.

17. Curtis, p. 336.

18. Ibid., p. 417.

19. Encyclopedia of American Biography, p. 412.

20. Curtis, p. 477.

21. Detroit Free Press, 6 Feb, 1891.

22. Curtis, p. 478.

23. “Colonel Morrow’s Report”, p. 57.