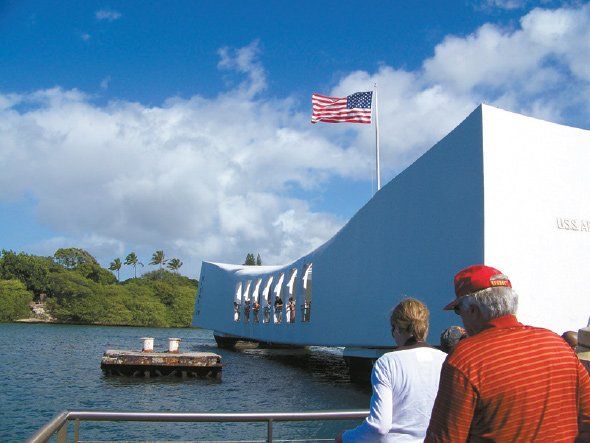

The Arizona Memorial, Pearl Harbor

On December 7, we will pass the 80th anniversary of the terrible attack at Pearl Harbor. Soon “Remember Pearl Harbor” became the battle cry as thousands of U.S. citizens signed up for war. In spite of being the beginning of World War II for America instead of the middle of the Civil War, Pearl Harbor was eerily similar to Gettysburg. Here are some points of interest comparing the Pearl Harbor attack with the equally pivotal Battle of Gettysburg:

Both Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor were a surprise – at least to some of their combatants. Robert E. Lee had not expected the Union to follow him so quickly and so well concealed from Virginia as he headed north into Pennsylvania with his army. When the battle began in the morning of July 1, 1863, Lee was several miles away in another town. In a similar vein, during the early morning hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, residents of Honolulu, airmen at Hickham Field, soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Kamehameha, and the U.S. Naval Fleet at Pearl Harbor had no inkling that planes bearing the symbol of the rising sun were headed straight for them – with deadly accuracy.

The Confederates in the summer of 1863, like both the Americans and the Japanese in late 1941, believed in their own invincibility. During the summer of 1863 the Army of Northern Virginia was in the best shape of its life. They had defeated the Union soundly at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Though they were suffering from exposure and malnutrition, they enjoyed high morale. Their determination to take the Union in their own territory increased their confidence of victory.1

In 1941, the ominous feeling of world-wide war was palpable as the Japanese Empire had already invaded Indochina. Their allies, the Nazis, had done the same in Europe (except for Great Britain) and Northern Africa. Hirohito, the young Japanese emperor, had been influenced by his inner circle of counselors to overtake the myriad British, Dutch, and French colonies in Asia and the Pacific, since the Allies had an overwhelming task to stop Hitler and couldn’t be bothered with their distant lands.

Hirohito realized that the only nation powerful enough to prevent them from taking over much of Southeast Asia and most of the South Pacific was the United States. The U.S. had recently placed an embargo on Japan for their recent atrocities in China. Japan needed American oil for their planes, ships, and submarines.

The Americans should have foreseen this issue, but, like the Confederates approaching Gettysburg, they felt they could easily defeat the island nation. “The Japanese are not going to risk a fight with a first-class nation,” claimed one Pennsylvania congressman that year. Commander Vincent Murphy, one of Admiral Husband Edward Kimmel’s assistants agreed. “I thought it would be utterly stupid for the Japanese to attack the United States at Pearl Harbor,” he said. Admiral Kimmel, also complacent, trusted his subordinates who were more concerned about local sabotage than a surprise attack. They were all, tragically, wrong.2

Both attacks occurred early in the morning. The Battle of Gettysburg commenced at about 7:30 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, 1863 as the Confederates were heading into town for supplies and encountered Buford’s cavalry instead. The Japanese pilots dropped the first bombs and torpedoes at Pearl Harbor about 7:53 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, 1941.

Warnings had been issued – and ignored. When Brigadier General J.J. Pettigrew from North Carolina – a man new to the Army of Northern Virginia – noticed Buford’s troops near Gettysburg, he immediately warned General A.P. Hill, the new commander of the equally new Third Corps. Hill duly ignored Pettigrew, thinking him mistaken. Amazingly similar were the multiple warnings given to the U.S. Navy that the Japanese were planning an attack on Pearl Harbor. Nearly a year before the bombings, the U.S. Ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, learned about the detailed plans. He warned President Roosevelt of the coming assault, emphasizing that it would come “ with dramatic and dangerous suddenness.” Roosevelt did not believe him. When an urgent message was relayed to the State Department at the end of November 1941, that the Japanese fleet had departed en masse on the Pacific, heading east, that warning, too, went unheeded.3

On the morning of that fateful December day, members of the U.S.S. Ward spotted and sank a Japanese submarine near the harbor entrance. Since the presence of the enemy submarine was an act of war, they immediately reported the incident. Their commanders were dismissive. Minutes later, army privates monitoring the military radar at Pearl Harbor noticed a distinctive blip – planes approaching from the East. When they reported it, they were told that a group of B-17 planes were heading to Pearl Harbor from San Francisco. Since the planes were coming from Asia, eastward, and not the direction from the U.S. mainland, the lieutenant dismissing the warning was inexcusable. And it would cost over two thousand four hundred lives.

Both sides used extensive intelligence to monitor their enemy’s strategy. “All warfare is based on deception,” wrote Chinese soldier Sun-Tzu in 500 B.C. “If the enemy leaves a door open, you must rush in.” The doors were indeed ajar at Gettysburg in 1863 and in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor in 1941.4

Both Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor were a surprise – at least to some of their combatants. Robert E. Lee had not expected the Union to follow him so quickly and so well concealed from Virginia as he headed north into Pennsylvania with his army. When the battle began in the morning of July 1, 1863, Lee was several miles away in another town. In a similar vein, during the early morning hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, residents of Honolulu, airmen at Hickham Field, soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Kamehameha, and the U.S. Naval Fleet at Pearl Harbor had no inkling that planes bearing the symbol of the rising sun were headed straight for them – with deadly accuracy.

The Confederates in the summer of 1863, like both the Americans and the Japanese in late 1941, believed in their own invincibility. During the summer of 1863 the Army of Northern Virginia was in the best shape of its life. They had defeated the Union soundly at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Though they were suffering from exposure and malnutrition, they enjoyed high morale. Their determination to take the Union in their own territory increased their confidence of victory.1

In 1941, the ominous feeling of world-wide war was palpable as the Japanese Empire had already invaded Indochina. Their allies, the Nazis, had done the same in Europe (except for Great Britain) and Northern Africa. Hirohito, the young Japanese emperor, had been influenced by his inner circle of counselors to overtake the myriad British, Dutch, and French colonies in Asia and the Pacific, since the Allies had an overwhelming task to stop Hitler and couldn’t be bothered with their distant lands.

Hirohito realized that the only nation powerful enough to prevent them from taking over much of Southeast Asia and most of the South Pacific was the United States. The U.S. had recently placed an embargo on Japan for their recent atrocities in China. Japan needed American oil for their planes, ships, and submarines.

The Americans should have foreseen this issue, but, like the Confederates approaching Gettysburg, they felt they could easily defeat the island nation. “The Japanese are not going to risk a fight with a first-class nation,” claimed one Pennsylvania congressman that year. Commander Vincent Murphy, one of Admiral Husband Edward Kimmel’s assistants agreed. “I thought it would be utterly stupid for the Japanese to attack the United States at Pearl Harbor,” he said. Admiral Kimmel, also complacent, trusted his subordinates who were more concerned about local sabotage than a surprise attack. They were all, tragically, wrong.2

Both attacks occurred early in the morning. The Battle of Gettysburg commenced at about 7:30 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, 1863 as the Confederates were heading into town for supplies and encountered Buford’s cavalry instead. The Japanese pilots dropped the first bombs and torpedoes at Pearl Harbor about 7:53 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, 1941.

Warnings had been issued – and ignored. When Brigadier General J.J. Pettigrew from North Carolina – a man new to the Army of Northern Virginia – noticed Buford’s troops near Gettysburg, he immediately warned General A.P. Hill, the new commander of the equally new Third Corps. Hill duly ignored Pettigrew, thinking him mistaken. Amazingly similar were the multiple warnings given to the U.S. Navy that the Japanese were planning an attack on Pearl Harbor. Nearly a year before the bombings, the U.S. Ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, learned about the detailed plans. He warned President Roosevelt of the coming assault, emphasizing that it would come “ with dramatic and dangerous suddenness.” Roosevelt did not believe him. When an urgent message was relayed to the State Department at the end of November 1941, that the Japanese fleet had departed en masse on the Pacific, heading east, that warning, too, went unheeded.3

On the morning of that fateful December day, members of the U.S.S. Ward spotted and sank a Japanese submarine near the harbor entrance. Since the presence of the enemy submarine was an act of war, they immediately reported the incident. Their commanders were dismissive. Minutes later, army privates monitoring the military radar at Pearl Harbor noticed a distinctive blip – planes approaching from the East. When they reported it, they were told that a group of B-17 planes were heading to Pearl Harbor from San Francisco. Since the planes were coming from Asia, eastward, and not the direction from the U.S. mainland, the lieutenant dismissing the warning was inexcusable. And it would cost over two thousand four hundred lives.

Both sides used extensive intelligence to monitor their enemy’s strategy. “All warfare is based on deception,” wrote Chinese soldier Sun-Tzu in 500 B.C. “If the enemy leaves a door open, you must rush in.” The doors were indeed ajar at Gettysburg in 1863 and in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor in 1941.4

The sunken U.S.S. Arizona is still visible

The Japanese would never have attempted such a bold attack on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor without the gathering of significant intelligence. Bernard Kuehn, a Nazi spy, attended classes at the University of Hawaii. In his spare time, he counted the U.S. ships in the harbor and relayed the information to Japan. The Japanese Consul General in Honolulu, Nagao Kita, had his own spy ring. His 27-year-old clerk, Yoshikawa, went twice a week to Pearl Harbor to count the ships and then to nearby Hickham airfield to count the planes. He had noticed that the number of ships swelled on the weekends, helping to determine a weekend attack.5

The Japanese high command over the Pearl Harbor attack, like Generals Lee and Longstreet at Gettysburg, strongly disagreed on their plans of attack. Lieutenant General James Longstreet was Lee’s second in command at Gettysburg. He vigorously took exception to invading Pennsylvania, preferring to keep to defensive campaigns. When the South emerged victorious from the first day’s battle at Gettysburg, General Lee wanted to continue the fight, even though the Union soldiers were firmly entrenched on high ground between Lee and Washington – the true objective. Longstreet, who understood numbers and the value of high ground, vigorously opposed the idea. Lee should have listened to him.

Like General Longstreet, Vice Admiral Nagumo believed that flying hundreds of planes over such a long distance to Hawaii, the most isolated archipelago in the world, was rather idiotic and fraught with the chance for disaster. He felt a nagging concern that the United States would not take the assault with the measure of meekness that his commander believed they would do. He explained that “it was all well…to go into the tiger’s lair if you wanted the tiger’s cubs, but what about the tiger ?” He was proved correct, once the tiger was awakened, its ferocity did not abate until Japan suffered an ignominious defeat nearly four years later.6

Like Gettysburg, Pearl Harbor was just a means to an end. Robert E. Lee did not want Gettysburg – he had not even planned to fight there. Washington, the Federal capital, was his real objective. In that same vein 78 years later, Japanese commander Yamamoto really wished to do the bidding of the Imperial Emperor to take over the islands of the Pacific and Southeast Asia – eventually all of Asia, in fact. In order to obtain that objective, the U.S. Pacific fleet had to be destroyed.

In all, eight battleships were moored at Pearl Harbor. Each was named after a corresponding U.S. state: the Arizona, the California, the Maryland, the Oklahoma, the Pennsylvania, the Nevada, the Tennessee, and the West Virginia. The U.S.S. Utah, also docked at Pearl Harbor, was a former battleship that served as a gunnery training vessel. There were many other ships in the harbor too – many seaplane tenders (such as the U.S.S. Curtiss ), 29 destroyers, eight mine-layers, and over a dozen light cruisers, about 186 ships in all. Within the narrow inlet and shallow waters of the harbor, these ships and their crews were veritable sitting ducks. When the Japanese attacked, most were hit and damaged, some severely, and a few fatally. With the exception of three U.S. aircraft carriers, which were all at sea doing maneuvers (the Lexington , the Enterprise and the Saratoga ), the rest of the fleet were damaged – yet most were not completely destroyed. The destroyer, the U.S.S. Shaw , was split in two with deadly explosions. Yet, it was raised and repaired, and saw action during the war. Both the California and the West Virginia were sunk in the harbor with heavy casualties, but they, too, were repaired and aided in the eventual defeat of their attackers in the Pacific Theater.7

The high command of both General Lee and Admiral Kimmel were reluctant to rid themselves of ineffectual cronies and replace them with competent commanders. Mistakes at Gettysburg were made by both sides of the conflict, and Lee might have won at Gettysburg had he replaced Jeb Stuart and William Pendleton, his chief of artillery. Had the Confederates employed a more astute cavalry leader, they would not have been caught unaware in Pennsylvania. And, during Pickett’s Charge, Pendleton actually took artillery and ammunition off the battlefield – a disastrous mistake for the South. The aging Dr. Pendleton, though, was a longtime friend of both Lee and Jefferson Davis – and his mistake during Pickett’s Charge lost the war for the South – they just didn’t know it yet.

In the same manner, Admiral Kimmel, in charge of the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, allowed inept subordinates to continue their high-level jobs. Rear Admiral Claude Bloch and Lt. General Walter Short were, after all, his golfing buddies. Bloch was the man who ignored the warning about the submarine in the harbor. Short, the man in charge of protecting the ships in the harbor scoffed at the rumors that the Japanese were about to attack. As a result, the sailors and soldiers at Pearl Harbor and Fort Kamehameha were never trained for a frontal attack. When the attack came, they could do little to stop it. In all, twenty ships and 150 planes were destroyed or heavily damaged, and over 2400 Americans, military and civilians, were killed.8

Admiral Kimmel, too, was guilty of careless behavior. He discouraged long-range scouting at sea, calling it unnecessary. Admiral Yamamoto’s success at Pearl Harbor was largely aided by the slackened practices, even ineptness, of these men.

Like Meade at Gettysburg, Yamamoto did not press his advantage – with disastrous results. The sheer numbers of dead and staggering destruction after Gettysburg gave George Meade pause. Not knowing if General Lee would stay or go, Meade knew he needed to remain on the field to claim victory for the battle – stipulated by the Napoleonic rules of warfare. Meade desperately needed the win at Gettysburg, and by staying on the field, for a time, after Lee vacated it, he was able to secure the Union victory. Unfortunately for Meade, Lee was an aggressive defender, and by the time Meade moved his army in pursuit of Lee, the Army of Northern Virginia were deployed on high ground south of Gettysburg. Contemporaries in Washington, and many historians, blame Meade’s slowness for Lee’s escape across the Potomac – and the continuation of the war for nearly two more years. In spite of Meade not following up his advantage at Gettysburg, the Union still won the war.

The same could not be said for the Japanese Empire. Although Yamamoto’s plan was executed with great success, the Japanese pilots failed to destroy the many oil storage tanks that rested safely on Oahu. They were unable to locate the three aircraft carriers at sea. The U.S. submarine base on Oahu was not even attacked. Moreover, most of the ships were repaired to be used with tenacity against their enemy, and the concern of Vice Admiral Nagumo was realized – the sleeping tiger was suddenly awakened, and ready to avenge what had happened.9

Blame and political fallout resulted after both Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor. Surprisingly, Robert E. Lee was not reprimanded in Richmond for his terrible loss at Gettysburg. Instead, George Meade was raked over the political coals in Washington. Dan Sickles, a New York congressman who was wounded at Gettysburg, had disobeyed Meade’s orders and moved his men away from the main Union line, resulting in disaster for his corps. Eager to deflect the blame for his own insubordination, Sickles used the press and his own political allies in an attempt to destroy Meade’s reputation and get him relieved of command. Eventually, Meade was exonerated – and remained the commander of the Army of the Potomac until Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Three quarters of a century later, Admiral Kimmel and Lt. General Short were relieved from command for dereliction of duty. Kimmel spent years trying to clear his name, and welcomed a Congressional probe. He and Short were eventually cleared of the charges.10

Both places experienced vast devastation, death, and human suffering. Gettysburg was ravaged with warfare, and its landscape marred. The stench of death and rot pervaded the area even when Lincoln visited four months later. Thousands were killed. Over 20,000 wounded from both sides were left behind in the town, many of those with mortal wounds. Civilians were left, for the most part, to care for the suffering and dying. With crops destroyed, livestock taken or killed, homes and barns filled to capacity with soldiers, Gettysburg was so ruined that it took years for the town to recover.

Though the dead and wounded at Pearl Harbor paled in comparison to Gettysburg’s three-day battle, it is important to realize that the attack there lasted only about an hour, with over 2400 left dead in its wake. Of that number, only 55 were Japanese pilots, and the unfortunate men in the submarine that was sunk before the attack. The rest were all Americans. The largest single place of casualties, most of them fatal, was upon the U.S.S. Arizona. Most of the crew, remembered one of the few who survived, were “ gone in an instant flash of light.” Among the survivors were the few who had arisen early to attend church or were on deck. A few, like seaman Don Stratton, survived because a fellow sailor from another ship threw a lifeline, allowing him to grab a rope and pull himself to safety. Over nine hundred, though, sank with the Arizona, and are still entombed within the harbor. Another 217 died after being fished out of the water, severely burned. The ship with the next highest casualties was the Oklahoma, which took three torpedo hits from low-flying planes. One of the ship’s survivors remembered seeing a pilot laughing at the chaos he had caused. Don Stratton remembered the same from the Arizona. Other battleships with significant damage and deaths included the Utah, the West Virginia, the Maryland, the California, and the Pennsylvania.11

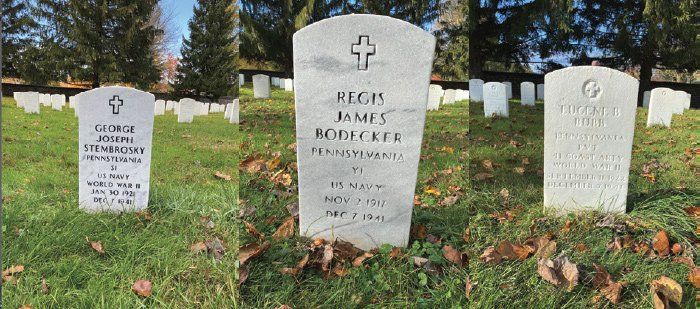

Other ships, such as the seaplane tender U.S.S. Curtiss, destroyers like the U.S.S. Shaw, and light cruisers like the U.S.S. Helena, were also hit. Their numbers did not approach the deaths on the Arizona, but the unfortunate sailors and Marines were just as dead. Two of them were Pennsylvania natives George Stembrosky and Regis Bodecker. Stembrosky, age 20, was unmarried; Bodecker, 24, was married and the father of a young child. The explosion on the Helena blew him into the firy waters, where he was rescued and sent to the hospital. He died there later that day with third-degree burns.12

Some of the crews on the Arizona and the Oklahoma who survived the bombings were trapped beneath the hulls of these sinking ships. The Arizona and the Oklahoma were two of the three ships that were not resurrected. The trapped crewmen from the Arizona were not rescued. Eighty years later, they remain buried with their ship. The survivors from the Oklahoma , however, were eventually freed from the hull in time. One sailor remembered that it was like “being dug out of your own grave.”13

The public reaction to Pearl Harbor mirrored that of those who were incensed at the numbers of slain at Gettysburg. The outcry that followed both events was stirring. It united the people and galvanized them into action. At Gettysburg, the phalanx of dead necessitated their interment at Gettysburg. When Abraham Lincoln came to the town to offer his poignant Gettysburg Address, many journalists sneered but the public agreed that the “government of the people ” could not perish. After Pearl Harbor, the American public was acutely angry and distressed at the impunity of the attack. To them, the slain at Pearl Harbor had been murdered. They went, eagerly, to war.14

Both Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor are National Cemeteries. On Cemetery Hill at Gettysburg, the nation’s first National Cemetery was dedicated on November 19, 1863. Over 7500 graves from all of America’s wars since the Civil War are situated there. Over 3500 are Union slain from the Battle of Gettysburg. Half of them are unknown. Among those buried in the World War II section are three men who died at Pearl Harbor: George Stembrosky, Regis Bodecker, and Eugene Bubb. Bubb served in the army, and was not on one of the ships in the harbor at the time of the attack. Instead, he was a soldier on duty at nearby Camp Kamehameha. It is not clear how the York native perished. At Pearl Harbor, the sunken U.S.S. Arizona is a National Cemetery. The names of the 1177 men who perished aboard ship that fateful day are respectfully listed on the Wall of Honor, etched into the back wall of the memorial. A noteworthy addition shows additional names on a small marble catafalque to the front of the wall. The names are those of the survivors of the Arizona who wished to be entombed with their crew at their deaths.15

“Pearl Harbor Never Dies” and neither will Gettysburg. The slogan, written by one of the attorneys for Admiral Kimmel, is succinct and completely on point. Pearl Harbor, like Gettysburg, is going to be remembered, and visited, for many years to come. The unexpected, and the unthinkable, happen. We must be prepared to face these devastating possibilities as long as we cherish our liberty – something that seems precarious in every generation. By remembering these two turning points in American history, we are also reverencing those who fought and sacrificed for us, many of them in the last fight of their lives, so that we have a fighting chance.16

Bubb, Bodecker, Strembrosky

End Notes:

1. Coddington, pp. 24-25.

2. Prange, pp. 21, 35-36, 404. Stone, p. 10. U.S.S. Arizona Memorial.

3. Pfanz, p. 53. Wilson, p. 55. Stone, pp. 13-14. Prange, pp. 448, 500.

4. Prange, pp. 310.

5. Longstreet, p. 324. Prange, p. 313.

6. Longstreet, p. 347. Stone, p. 5. Prange, p. 389.

7. Stone, p. 10. U.S.S. Arizona Memorial, Pearl Harbor.

8. Pfanz, pp. 294-295. Alexander, p. 420. Prange, pp. 360, 414, 731. Stone, pp. 50-51.

9. Coddington, p. 550. Prange, pp. 546-547. Stratton, p. 136.

10. Coddington, p. 573. Stone, p. 47. Prange, p. 701.

11. Stratton, p. 113. Of the damaged and destroyed ships in the harbor, only three were not raised: the Arizona, the Oklahoma, and the Utah.

12. Stone, pp. 49-51. “These Honored Dead”, Gettysburg Blog, Oct. 2, 2015.

13. Prange, p. 562.

14. Loski, pp. 27-28. The Soldiers’ National Cemetery, Gettysburg. Stone, p. 51.

15. “These Honored Dead”, Gettysburg Blog, Oct. 2, 2015. Stratton, p. 144. When Stratton died in 2020, he was buried in his local cemetery, instead of with his crew at the Arizona.

16. Prange, p. 739.