Midway & Gettysburg:

Two of the Greatest Battles in American History

by Jeff Harding

In both battles, the invading forces exhibited an overwhelming level of overconfidence. The Army of Northern Virginia, under General Robert E. Lee, and the Imperial Japanese Navy under Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, entered preparations for their campaigns riding a crest wave of victories. In both cases, the intoxicating aftereffects of these victories led to an unparalleled level of overconfidence. Both Lee and Yamamoto displayed a corresponding disregard for the capabilities of their adversaries. In the aftermath of Midway, the Japanese dubbed this malady “Victory Disease”.2

When Lee’s army entered the Gettysburg Campaign on the heels of Lee’s most stellar victory, the Battle of Chancellorsville, they were “blinded” by their string of victories. The Confederates seemed not to have considered the fact that the blue-clad men of the Army of the Potomac might fight with increased tenacity once Lee’s men invaded Pennsylvania.

Lee and the rest of his high command also discounted important concerns, such as operating far from their base of supply, unfamiliarity with topography and geography, and operating in hostile territory. Complicating this, after Chancellorsville, Lee lost his most trusted subordinate, General “Stonewall” Jackson. As a result, Lee had to reorganize his army. Here was a situation ripe for failure. Yet, Lee’s army considered these issues inconsequential. Like the Imperial Japanese Navy eighty years later, the Confederates were completely blinded by Victory Disease. They should have anticipated the threats, but continuous success and overconfidence dazzled Lee and his army so that they ignored what some term as “predictable surprises.”3

One needs to look no further than the Japanese tabletop war games to find the same level of overconfidence. Time after time, the Japanese commanders refused to give even the slightest consideration to the possibility for U.S. naval success. In one instance, when a given scenario suggested that the U.S. forces might actually sortie to Midway in advance of Japanese forces, leadership quashed the exercise by claiming that it was unfairly unrealistic. In another instance, when the game’s role of the dice (to provide an element of chance in every scenario) resulted in the sinking of two Japanese aircraft carriers, the referees overruled the outcome. Instead, they allowed only one carrier to be sunk. Later, in the games, they resurrected the ship to full duty. As the war games continued, the referees altered the rules so that the U.S. fleet could never prevail. In the actual battle, all four Japanese carriers were sunk. The Japanese rued their failure to consider the realistic alternatives to their war games.4

On the eve of both battles, the victorious forces changed their leaders. It is interesting to note that both the Army of the Potomac and the U.S. Naval Forces at Midway operated under new leadership. In both cases, the changes occurred at the eleventh hour.

For the Union army, the new commander was Major General George Gordon Meade. Promoted to lead the Army of the Potomac just three days prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, Meade was thrust into a crucial role at a critical moment in time, and with little time to prepare. This was remarkable when one considers that up to that time, the Army of the Potomac had been soundly defeated by Robert E. Lee’s army numerous times.

Meade took over in the wake of a series of failed army commanders. Also, by the time Meade had assumed command, Lee’s troops had stolen a march on his forces, with the bulk of the Confederate troops operating in Pennsylvania. Meade had to act fast. If he were to fail at Gettysburg, Lee’s army may well have an opportunity to march on Washington, D.C.5

The U.S. Navy faced similar circumstances at Midway. The Pacific Fleet had two new commanders, one at the strategic level and one at the tactical level. After the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt sent Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to assume command at Pearl. When the President appointed Nimitz, he did not mince words: “Tell Nimitz to get the hell out to Pearl and stay there till the war is won.”6

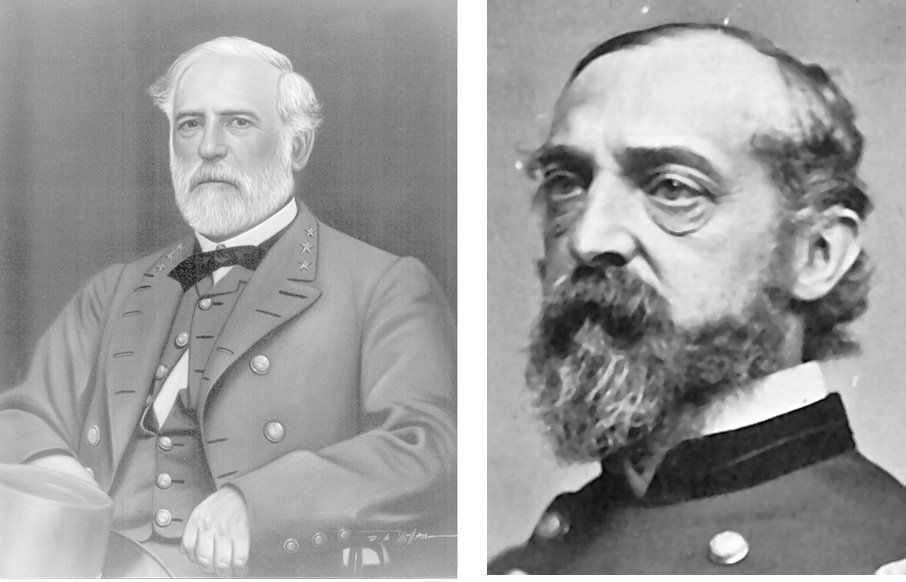

General Robert E. Lee (l.) and Maj. Gen. George Meade

(Library of Congress)

Also, just prior to Midway, there was a critical change in task force leadership. This change centered on Task Force 16, which included two carriers, the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and the USS Hornet (CV-8), and their escort ships. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, one of the early heroes of the war, normally commanded this unit, but during a recent patrol he had contracted a chronic case of dermatitis, and was sidelined. Nimitz selected Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance to replace Halsey. The other task force admiral was Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, who commanded Task Force 17, which included the USS Yorktown (CV-5) and its escorts. Fletcher ranked Spruance, but Nimitz smoothed over the problem of having two admirals sharing tactical command by arranging things so that Fletcher commanded the newly combined Carrier Strike Force (TF 16 and TF 17). This force represented the last effective line of defense against the Japanese fleet. Nimitz was “all in” with every aircraft carrier available to him. Much like Meade at Gettysburg, Nimitz shouldered a tremendous responsibility. If Midway fell, Pearl Harbor and perhaps the west coast of the United States would be in serious peril. The fate of the war was in the balance.7

Both the Army of Northern Virginia and the Imperial Japanese Navy lacked crucial intelligence. At the outset of the Gettysburg Campaign, as the Confederates headed north through the Shenandoah Valley, General Lee approved a special mission for his most reliable intelligence gathering unit, General Jeb Stuart’s division of cavalry. The mission involved Stuart circumnavigating the entire Union army in order to gather intelligence while simultaneously disrupting Union communications. Unfortunately for Lee, Stuart’s troops were caught off-guard by the faster-than-anticipated movement of the Union forces. In a matter of days, Stuart’s Division was cut off from the rest of Lee’s army, and could not provide Lee with the intelligence he needed.8

Also, save for a last-minute report provided by a spy, Lee was left in the dark with regard to the whereabouts of the entire Union army. Lacking intelligence from his most trusted source, Lee turned to his infantry to sweep the countryside for information. By asking foot soldiers to suddenly fill the traditional role of cavalry, Lee inadvertently caused his men to stumble into battle on July 1, 1863.9

From the planning stages right up to the commencement of the Battle of Midway, the Japanese fleet suffered from a startling lack of accurate information concerning the location and size of the U.S. naval forces. Their most important intelligence-gathering mission, called Operation K, failed only four days before the battle. Under this plan, on May 31, a last-minute effort to determine if the U.S. fleet was still at Pearl Harbor was planned by launching two seaplanes from Wotje Island. But, the Japanese were forced to cancel this mission when several U.S. ships unexpectedly appeared at the seaplane refueling rendezvous, French Frigate Shoals. The failure of Operation K, and the Japanese Navy’s failure to establish a submarine picket line in time to track American carriers as they left Pearl Harbor, put the Japanese fleet into an informational blackout. As they sailed toward Midway, so far as the admirals knew, the U.S. carriers were still in port at Pearl Harbor, even though they had no proof to confirm it. When the U.S. carrier planes made their appearance at Midway, it surprised every Japanese commander on the command bridge.10

The victorious forces of both battles possessed abundant intelligence. On the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union army possessed excellent intelligence, thanks to the stellar efforts of Brigadier General John Buford, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division. Leading up to the battle, Buford provided his superiors with a series of detailed reports, accurately conveying the location of each of Lee’s three corps and the direction in which they traveled toward Gettysburg. General Meade benefited greatly, too, from the army’s formal intelligence gathering organization, the Bureau of Military Information, which operated under the direction of the Union Army’s provost marshal, Brigadier General Marsena Patrick. Much of the information provided to General Meade before and during the battle by this bureau proved accurate and useful.11

During the Pacific War, the U.S. Navy code breakers executed a phenomenal intelligence coup. A few months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy cryptanalysts in Hawaii began deciphering portions of Japan’s operational code. Throughout the spring of 1942, the U.S. unit’s indomitable chief, Commander Joe Rochefort, and Admiral Nimitz’s cunning intelligence officer, Lt. Commander Edwin Layton, worked tirelessly to predict Japan’s next move. Layton’s faith in Rochefort and his team was crucial. In turn, Admiral Nimitz trusted and relied on Layton’s advice. Ultimately, this team of code breakers provided Nimitz with nearly every card he needed to play a “winning hand” at Midway.12

Admiral Nimitz trusted the information provided and acted upon it accordingly. The intelligence gleaned by Rochefort’s team revealed key portions of Japan’s battle plan for Midway. This time, the Japanese planned to sink the U.S. Navy’s entire Pacific Fleet of aircraft carriers and gain possession of a suitable base at Midway to launch future attacks on Hawaii. It seemed a perfect ambush.13

However, a series of key decryptions and corresponding analysis conducted by Rochefort and his team enabled Layton to predict the day the Japanese carrier force would attack (June 4), the likely time they would be sighted (0600 hours), the direction from which they would approach (a course bearing 315 degrees – due northwest) and how far from Midway the Japanese fleet would be when first sighted (175 miles). As a direct result of this crucial information, Nimitz developed a plan to sortie his carrier forces early and lie in wait, thereby turning the planned Japanese ambush into an American one. As it turned out, Layton was spot-on with his predictions. He correctly identified the date and only missed the time, course, and distance by five minutes, five degrees, and five miles.14

Each battle proved to be a key turning point, from which there was no return. The defeated Confederates at Gettysburg and the Japanese fleet at Midway each suffered cataclysmic losses from which they would never recover. The Confederates lost approximately 28,000 soldiers (killed, wounded, captured and missing), or 40% of their army, in the Gettysburg Campaign. Lee’s army could ill afford these losses. Worse yet, these losses included six generals killed and ten generals wounded. Overall, the Confederates suffered no fewer than nineteen casualties among the forty-six division and brigade commanders. Nearly fifty percent lost their regimental commanders. These men lost tended to be among the army’s finest. As one Confederate officer put it, just days after the battle when reflecting on his army’s colossal loss at Gettysburg, “We gained nothing but glory, and lost our bravest men.”15

For the Imperial Japanese Navy, losses came in manpower and war-fighting material. The Japanese lost four large aircraft carriers and one heavy cruiser, with a cruiser and several destroyers damaged. These carriers were among the six used in the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor six months earlier. The Japanese also lost 257 aircraft, either shot down or destroyed when the carriers sank. Worse yet, the Japanese lacked the industrial capacity to replace these carriers and planes with any speed. During the remainder of the Pacific War, Japan launched only two new large aircraft carriers. Just as important, they lost over 3,000 men, including many of their best pilots. For various reasons, Japan did not construct an effective pipeline to replace these aviators who were lost with men of equal skill. Like the Confederates at Gettysburg, the Japanese were never able to recoup their losses.16

The victorious commanders suffered public criticism because they did not annihilate the enemy. After Gettysburg, critics complained that General Meade had faltered by not counterattacking during the late afternoon of July 3, immediately after the repulse of Longstreet’s ill-fated assault (better known as Pickett’s Charge). Many felt that the severely weakened Confederate forces were vulnerable to a counterattack. Recognizing potential disadvantages to such a tactical endeavor at such a late hour, Meade chose to remain in a defensive posture. Today, most historians feel he was correct to do so.17

Meade endured even more criticism following the ten-day pursuit of the retreating Confederate forces. But, most of Meade’s critics were not present to see what Meade saw. Meade knew that his army had also suffered tremendous losses (calculated at 23,000 or 25% of his forces). Nor did Meade’s critics understand that the Union army undertook significant efforts to seriously harm Lee’s retreat. They failed to recognize that Meade did indeed seek an opportunity to strike a crippling blow at the Confederates at that time. Today, historians view Meade’s actions as wise, aggressive enough, and suitable, considering the circumstances.18

Similarly, Admiral Spruance, who assumed independent operational command of Task Force 16 from Admiral Fletcher late in the afternoon of June 4, 1942, was roundly criticized by some for not seeking to completely destroy the Japanese fleet, after sinking four carriers at Midway. Most of this criticism focused on Spruance’s lack of action on the nights of June 4 and 5. Specifically, some believed that Spruance should have sailed west to seek battle with either Yamamoto’s Main Body or Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake’s ‘Midway Invasion Force’. Certainly, having sunk all four carriers created an opportunity, but what the critics failed to realize is that Spruance acted within the boundaries of the orders given to him by Admiral Nimitz. Just before the battle, Nimitz advised Fletcher and Spruance as follows: “ You will be governed by the principle of calculated risk, which you shall interpret to mean the avoidance of exposure to attack by superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting, as a result of such exposure, greater damage to the enemy.”19

Spruance recognized the risks in pursuing the Japanese. Any night carrier operations required illumination, which would attract Japanese submarines. Therefore, he moved away from the enemy forces on the night of June 4 to open distance between the surviving fleets. After midnight, Spruance reversed course and picked up his pursuit of the surviving Japanese forces. He ordered a number of subsequent attacks that ultimately resulted in the sinking of a significant Japanese warship, the heavy cruiser Mikuma, and the damaging of another cruiser, the Mogami. He also made the unprecedented decision to have his carriers turn on their search lights and illuminate their decks to allow for a rare night landing, made necessary by an unexpected extension of daylight operations. In the end, most naval historians agree that Spruance’s cautious yet steady pursuit was proper.20

The eminent naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison likely said it best in describing Admiral Spruance’s performance at Midway. Morison called him “ superb ,” saying that Spruance was “ Calm, collected, decisive, yet receptive to advice; keeping in his mind the picture of widely disparate forces, yet boldly seizing every opening …” Morison concluded that Spruance emerged from the Battle of Midway as “ one of the greatest admirals in American Naval history.”21

Sources: Bazerman, Max H. and Michael D. Watkins. Predictable Surprises. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2008. Buell, Thomas B. The Quiet Warrior. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Hessler, Hames A. and Wayne E. Motts. Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie LLC, 2015. Kleiss, N. Jack “Dusty”. Never Call Me Hero . New York: HarperCollins, 2017. Layton, Edward T. with Roger Pineau and John Costello. And I Was There. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985. Loski,Diana. “A Gettysburg Hypothesis”, The Gettysburg Experience Magazine, July 2019. Morison, Samuel Eliot. “Six Minutes that Changed the World”, American Heritage, February, 1963, vol. 14, issue #2 (americanheritage.com). Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Two Ocean War. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1963. Parshall, Jonathan and Anthony Tully. Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway . Washington, D.C., Potomac Books, 2005. Prange, Gordon W. with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon. Miracle at Midway. New York: Open Road Integrated Media Inc., 2018. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Pfanz, Harry W. with Scott Hartwig. The Battle of Gettysburg, Civil War Series . Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1994. Phipps, Michael and John S. Peterson. “The Devil’s to Pay”: Gen. John Buford, USA. Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth Military Impressions, 1995. Rigby, David. Wade McCluskey and the Battle of Midway . Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2019. Ryan, Thomas J. Spies, Scouts and Secrets in the Gettysburg Campaign . El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie LLC, 2015. Potter, E.B. Nimitz . Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976. Sears, Stephen. Gettysburg . Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Symonds, Craig L. The Battle of Midway . New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. Toll, Ian W. Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific 1941-1942. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2012.

End Notes:

1. Symonds, p. 197. Morison, Six Minutes That Changed the World.

2. Symonds, pp. 88-89. Toll, p. 380.

3. Bazerman and Watkins, pp. 72-80. Coddington, pp. 5-6. Sears, p. 1. Pflanz (CW Series), p. 2.

4. Symonds, pp. 176-179. Toll, pp. 381-383. Prange, pp. 33-34.

5. Coddington, p. 180. Sears, pp. 121-122. Pfanz, p. 5.

6. Potter, p. 9.

7. Potter, p. 19. Symonds, pp. 375-376.

8. Ryan, pp. 221-226, 232, 435. Coddington, pp. 107-113. Pfanz (CW Series, p. 5. Sears, pp. 103-106.

9. Ryan, pp. 277, 282-285. Pfanz, pp. 51-58. Coddington, pp. 181-182 and 263-264. Sears, pp. 123-124, 140-141, 153-162.

10. Parshall and Tully, pp. 97-104. Symonds, pp. 205-211. Toll, p. 406.

11. Ryan, pp. 5-6, 313-314, 326. Sears, p. 84.

12. Symonds, pp. 139, 185-188. Toll, pp. 304-305, 389-390.

13. The U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet carriers were out to sea during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

14. Layton, pp. 429-430 437-438. Symonds, pp. 136-139, 225, 228, 387-388. Potter, pp. 83, 93.

15. Sears, p. 498. Loski, pp. 63-71. Sears, pp. 498-499. Lt. John T. James, 11th VA Infantry, Pickett’s Division, GNMP Wayside Marker.

16. Parshall and Tully, pp. 417-420. Toll, pp. 476, 479. Symonds, pp. 360-361. Kleiss, p. 239.

17. Sears, p. 475. Hessler and Motts, p. 451.

18. Sears, pp. 481-497. Coddington, pp. 545-560.

19. Symonds, p. 335. Toll, p. 401. Potter, p. 87, 99-101.

20. Buell, pp. 154-155, 158. Symonds, p.347. Prange, pp. 346-347. This was during the evening of June 5.

21. Morison, p. 162. Prange, p. 403.

Jeff Harding’s career as a Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg National Military Park spans 22 years. A freelance historian with articles published in Naval History Magazine, Gettysburg Magazine and Civil War Times, he is a frequent contributor to The Gettysburg Experience. Jeff also serves as a leading consultant and motivational speaker. His recently released book, Gettysburg’s Lost Love Story: The Ill-Fated Romance of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt unravels numerous previously unknown facets of one of Gettysburg’s longest lasting mysteries. Jeff would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Craig Symonds, Richard Frank, and Dr. Timothy Orr in preparing this article.