One Nation, One Flag! Gettysburg's Grand Reunion

by Diana Loski

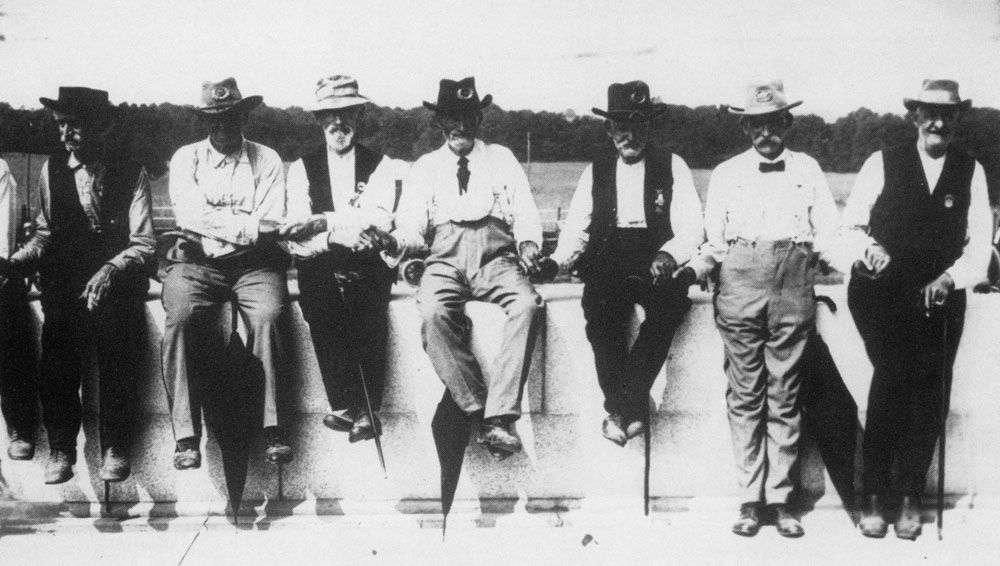

Another Pickett's Charge, 1913

(National Park Service)

Gettysburg is remarkable for three events and three only,” one veteran who attended wrote. “The Battle, Lincoln’s speech, and the Reunion.”1

The 1913 reunion at Gettysburg had been conceptualized by Gettysburg battle veteran and Pennsylvania native Henry S. Huidekoper and Gettysburg Park Historian Colonel John P. Nicholson. In 1908, thirty men were invited to Gettysburg’s Eagle Hotel to discuss the possibility of this great event. Twenty-eight came, and the concept formed into a plan. Over the next six years, committees met regularly; and the idea of a grand reunion, with a planned 40,000 Civil War veterans attending, slowly and carefully took shape.2

“The proposed observance of the anniversary will bring to the historic field of Gettysburg…the survivors of the great contending armies,” Pennsylvania Governor Edwin Stuart explained in 1908, “and will tend to intensify the feeling of brotherhood that insures to us a united country.”3

There was a lot to plan with so many people attending, especially a large number of them advanced in years and coming from great distances. Committees specialized in invitations and their acceptances, the scope and layout of the tent city that needed to be constructed to house the veterans, food and medical accommodations, events, hosts, guest speakers, special entertainments, transportation, sanitation, and supplies. The committees, which included state representatives, Civil War veterans, and local Gettysburg leaders, performed admirably; by the time the veterans arrived in Gettysburg, some as early as June 29, 1913 (when the “camp” officially opened), the town was ready for them – though many more veterans came than were originally expected. The slogan of the Grand Reunion was “One Nation! One Flag! The Star Spangled Banner.4

The tent city, constructed for the veterans, was located south of town where much of the battle had taken place. The city was five miles long and approximately two miles wide, with the Union veterans occupying the ground on Cemetery Ridge and southward toward the Round Tops; while the Confederates occupied the ground on Seminary Ridge and southward – where fifty years before Pickett’s men prepared for their famous charge. The tents were arranged in rows, forming “streets” that ranged from 1 to 15. Then, the tents were numbered from 1 to 49 so that the soldiers would be able to find their camp after tours, events, and, most important of all, visiting one another. Occasionally, a veteran would get lost, having forgotten to note his street number of the tent city, and only committing to memory the number of his tent. “Each camp commanded a fine view of the oth,” one veteran wrote. 5

“The tents were brown in color,” the same veteran recalled, “and were supposed to accommodate eight men. Each tent had cots, a galvanized iron pail, and two wash basins.”6

The tents were filled to capacity, 7,000 of them in all, in a city that surpassed by far the actual population of Gettysburg – much like the contending armies did in 1863. Regular Army soldiers and area Boy Scouts were assigned to aid the veterans, assisting them in multiple ways. The Red Cross had medical tents throughout the camps, with doctors on call. With the intense July heat and the frail health of many, the tents were well used, with over 700 patients during the event. The majority of the cases, it is documented, was due to the heat.7

While the State of Pennsylvania hosted the event and absorbed much of the cost, which totaled over $400,000; other states helped with the price of getting their honored veterans to the state of Pennsylvania, covering the cost of train fare. Once within the state of Pennsylvania, trains brought the veterans free of charge to Gettysburg. Street cars and motor cars were also available for transportation within the town, as the old soldiers wanted to visit the town and various areas of the immense battlefield. The town was festooned with red, white, and blue, with the reunion slogan visible throughout the area. Gettysburg thronged with people, masses of them, who wanted to participate in the celebrations and hoped to catch a glimpse of, or speak with, the veterans. One old Union soldier noted the “many Confederates ” there – and he was glad to see them.8

The battlefield also swarmed with humanity as the veterans wanted to return to the places where they had fought. Some took interested parties with them and gave them private tours. “We were able to locate our line and place of attack, ” one Union veteran recalled. “I was struck with the fact that my memory did not fail me,” a Confederate veteran remembered. Another favorite spot veterans visited was the grave of Jennie Wade, the only civilian killed during the battle. Her grave was found in Evergreen Cemetery.9

Sutlers, like in days of old, placed their tents throughout the camps during the reunion. “From the sutlers’ stores,” a journalist recorded, “was [sic] daily sold 200 gallons of ice cream, 25,000 bottles of soft drink, and 5000 cigars."10

The Chow Line

(National Park Service)

The soldiers were fed, in addition to main entrees, seasonal fresh fruits and vegetables for lunch and supper, and fresh bread for every meal. The meals were served in regular mess halls, built especially for the occasion. “The sight of the camp at mess call brought to my mind the scenes of long ago,” a Pennsylvania soldier remembered, “with the lines of men, each with a tin plate and cup, waiting his turn for the cook to serve him.” At the end of each meal, the leftovers were thrown out and burned. The camps were the “model of hygienic cleanliness” to keep illness and vermin to a minimum. Artesian water was distributed regularly throughout the camp, along with “ bubble fountains at every crossroads” and “coils of water packed in ice” to keep the men hydrated in the oppressive July heat.12

From July 1st through July 4th, special events were planned for each day. Guest speakers gave their oratories in a great tent constructed to house the myriad visitors. July 1st was “Veteran’s Day”, July 2nd was “Military Day”, July 3rd was “ Civic Day ” (a.k.a. “ Governors’ Day ” – as governors from many states, including Pennsylvania Governor John Tener, spoke to the assembled troops). On July 3rd there was a reenactment of Pickett’s Charge, with 1500 Confederates once again crossing the mile-wide field to a number of Union men waiting for them at their former line of battle on Cemetery Ridge. This time, there was a much happier culmination at the Angle, as men in gray were greeted with handshakes and embraces instead of loaded muskets. That night a fireworks display thrilled those who watched. July 4th was “National Day”, the culmination of the event, with President Woodrow Wilson as the keynote speaker.13

On Military Day, Alfred Beers, President of the Grand Army of the Republic, and Bennett Young, President of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, spoke to the phalanx gathered at Gettysburg. “The wounds of war are healed,” Beers said. “Peace and prosperity reign in the land. At no time in the history of the world has ever been witnessed a spectacle such as this, the voluntary meeting on a battlefield of those who constituted the armed forces who fought one another….The veterans of the North salute the veterans of the South with a feeling of joy in their hearts that the conflict is over, and that they can meet and greet each other as brothers.”14

When Bennett Young stood at the platform, he was greeted with a standing ovation – from both Union and Confederate veterans. The Kentucky native was visibly moved by the welcome. “I am more than a half-thousand miles from my home,” he began, “but all the same I am home. In this land, everywhere is my home. This country of ours, this glorious America, belongs to us all.” The memory of the last visit to Gettysburg evoked the strong impressions of “the rattle of musketry, the booming of cannon, the bursting of shells, the shouts of charging legions…” but he gladly spoke mostly of the present: “Time is not only a great vindicator, but it is also a great pacifier. Those who fought then now meet as friends. They grasp each other’s hands; they look kindly face to face. War’s animosities are forgotten; the noise of battle is hushed. Peace waves its hand over these bloodstained hills and cries out to war: Be still!”15

While the events were enjoyed by the visiting legions, most of the men just wanted to visit. There were many joyous reunions within the Grand Reunion. One of the first occurred on June 30th – before the official start of the Reunion, though many soldiers had already arrived. Walking down Confederate Avenue, two men were about to pass each other, when a spark of recognition lit up their eyes.

“I know you!” they said in unison.

Captain Ward Wallace of the 7th Texas Regiment and Edward Coward of the 2nd New York Cavalry had grappled one another in combat on July 2, 1863. The tree where they had met fifty years before stood close by. “Do you see that tree over there?” Coward said. “I saw you there on July 2, 1863!”

“You’re right,” Wallace agreed. “I know who you are! You’re that fellow who was hit in the leg and couldn’t run.”

“Yes,” corroborated Coward…. “And your fellows closed around me and captured me. I remember you well. You pointed a pistol at me and I [thought] you were going to shoot.”

“Mighty glad I didn’t,” Wallace replied. “For if I had this couldn’t have happened.”

The two men walked off together, “elated” at finding one another after half a century.16

Two others near the famous Angle had a similar experience. A.C. Smith of the 56th Virginia and Albert Hamilton of the 73rd Pennsylvania were standing at the High Water Mark, separately, with friends, explaining their respective experiences on July 3, 1863 – unaware that the other was there.

“Here it was!” Smith said, pointing to the stone wall where they had breached the Union line during Pickett’s Charge. “Here’s where we leaped across. I got a yard beyond that wall, I reckon, when I got hit and down I went. I remember a chap in blue coming on a run to me and giving me a drink of water. Then he picked me up and carried me off. Next thing I knew I was in a Yank hospital, and the boy who carried me was gone.” He paused, wistfully looking at the stone wall, and seeing things of a half-century past. “He’s gone to his reward by this time, I reckon.”

Hamilton, who stood only a few yards away, was busily engaged in a conversation of his own, and had not heard Smith’s narrative. “They got about to here,” he explained, “and then we beat ‘em back. And it was right here that a Johnnie fell…I lifted him up and gave him a swig of water, and then got him on my shoulders and carried him off…” It was then that Smith heard his words. He rushed forward, recognized the speaker and cried out, “Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord, it’s you, brother!” And the two former foes clasped each other in a mighty embrace.17

Some Reunion stories, however, did not have a happy ending. A group found a New York soldier standing mutely by a small, obscure monument, brushing the dirt from its corners, and wiping tears that would not stop.

“After the first day’s fighting,” he said, “I was left badly wounded, and they carried me away to a hospital.” He soon had a companion, a young man from Longstreet’s corps. “Next to me was a young southerner, a native of Georgia…We two chummed up as we lay in that hospital during the days that followed the battle, and he told me that his name was William Henry Scott. He told me of his plantation down South, and I told him of my home close to New York [City]. We liked each other, and there lying on those two cots, side by side, we grew to love each other, and we promised when each got better that we’d come and visit one another. Then we were parted. I was sent home, and he stayed behind to get well…But he never came to see me and, try as I would, I couldn’t get in touch with him. I waited and waited, trying often to get news about him, always hoping, believing that I’d see him. And then, I came down here, and I hoped I’d see him here.”

The veteran’s feelings rose to the surface and he paused to choke back tears that would not be restrained. “And here he is,” he said with difficulty. “Here he is…”

He pointed to the little stone almost covered by encroaching grass, inscribed simply “William Henry Scott”. He then buried his face in his hands and sobbed.

According to an observer, “Among his listeners there was scarcely a dry eye.”18

July 4, 1913 was a solemn day for the veterans. They rose in the morning and packed their personal belongings, ready for departure after the events of the day. It was National Day, a day of remembrance. “The United States Regular Army paid tribute today to the thousands who sleep under the hills of Gettysburg ,” the Raleigh Observer penned. “Somewhere down in the heart of the tented city a bugle rang out in silver sweet call that wandered over the field where Lee and Meade made history. Soldiers in the tent city stood at attention, followed by a 48-gun salute.”19

President Woodrow Wilson arrived that morning by train. On July 4, this Virginia native, who had met an aged Robert E. Lee when he was ten years old, addressed the veterans. His speech, though longer than Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, was still brief. “I need not tell you what the Battle of Gettysburg meant,” he began, “Fifty years have gone by since then, and I crave the privilege of speaking to you for a few minutes of what those fifty years have meant…They have meant peace and union and vigour, and the maturity and might of a great nation.” The President explained that although our nation had healed and prospered, its work was not yet finished. He waxed prophetic when he added, “The days of sacrifice and cleansing are not closed. We have harder things to do than were done in the heroic days of war…War fitted us for action and action never ceases…” He recalled the gallantry of the Civil War veterans, their duty now passed, their fighting days ended. It was now the turn of the next generations to rally them – and to be an example to the generations yet unborn. “What we strive for is their freedom,” President Wilson continued, “to lift themselves from day to day, and behold the things they have hoped for…”20

The return to Gettysburg, in peace and brotherhood, was the apogee for the veterans who attended. From high-ranking generals like Dan Sickles to the thousands of privates, the sons and grandsons of great generals like Longstreet and Pickett, and the coming together of civilians who had bandaged the wounds of the fallen, reuniting once again with those they aided, were all cathartic. With a Virginian once again in the White House, the cycle was at last complete. The war had ended, and the nation had not only survived, it had healed. The unity would be greatly needed in just a few short years, with the onset of a World War. It is a unity that is sorely needed today.

After the festivities on July 4th, the bands were hushed, the tents struck, and the soldiers headed for home. Some left in automobiles, but most took the train.

“Pathetic were the scenes at the departure of the veterans,” one veteran wrote. “The old boys realized that they would never again see their old comrades or their new-found friends. They clung in agony to the outstretched hands, and gripped again. ‘Good-by, Reb, good-by, old boy,’ one would call from the car window. ‘Good-by, Yank, good-by,’ came the reply, and then one would make a sudden rush across the tracks and grip…that old hand a gain that was thrust out from the open window…”21

“Who would have thought…fifty years ago these things would happen?” another veteran exclaimed. It had been a sublime experience, and unique to all of history. For Billy Yank and Johnnie Reb had met again at Gettysburg, as friends. “In all the marvelous things occurring in the Republic, there is nothing that is more wonderful than the scenes that [were] here at Gettysburg,” another observer noted.22

In the midst of the thousands of goodbyes that day in 1913, many were heard to say, “We will meet again in 50 years.” Perhaps, at some distant tent city, they did just that. They had reason to want to repeat the experience. During the Grand Reunion, under “One Nation, One Flag”, a Confederate veteran remarked, “They were the happiest set of old people I have ever seen.”23

The Blue & Gray at the Pennsylvania Memorial, 1913

(National Park Service)

End Notes:

1. Blake, p. 13.

2. Lewis, pp. 123-124. Beitler, pp. 7, 31, 59.

3. Beitler, p. 7.

4. Blake, p. 14. Lewis, p. 124. Beitler, p. 16.

5. Blake, p. 16.

6. Ibid. p. 15.

7. Beitler, p. 59.

8. “July 4th Events”, Raleigh Observer, July 5, 1913. “Participant Accounts”, Folder #11, Gettysburg National Military Park.

9. “Participant Accounts”, GNMP.

10. “The Great Reunion at Gettysburg”, Bucks Co., PA, July 26, 1913.

11. “Participant Accounts”, GNMP.

12. “The Great Reunion”, Bucks Co., PA, July 26, 1913. Blake, p. 18.

13. Tillberg, “A Century of Reunions”, GNMP.

14. Beitler, p. 102.

15. Ibid, p. 106.

16. Blake, pp. 20-21.

17. Ibid. pp. 22-23.

18. Ibid. pp. 24-25.

19. “July 4th Events”, The Raleigh Observer, July 5, 1913.

20. Beitler, p. 185-186. “July 4th Events”, The Raleigh Observer, July 5, 1913.

21. Blake, p. 200.

22. “Participant Accounts”, GNMP.

23. I bid.