General John Reynolds & Kate Hewitt:

A Tragic Love Story

by Jeffrey J. Harding

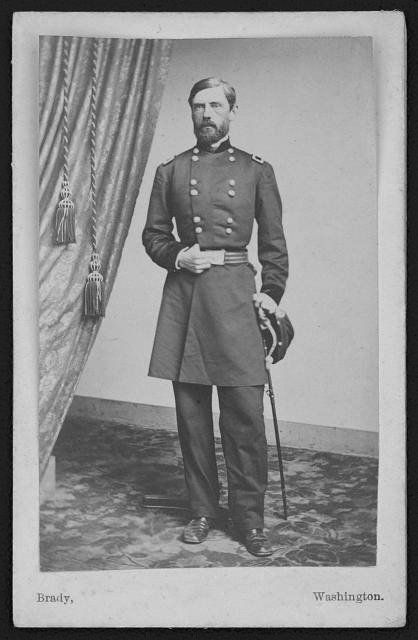

General John Reynolds (l.) (Library of Congress),

& Kate Hewitt (r.), (Courtesy of Kate Cleaver)

The following article offers highlights from the recently published book, Gettysburg’s Lost Love Story – The Ill-Fated Romance of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt, by Jeffrey J. Harding (Arcadia Publishing/History Press). The book is available from Arcadia (arcadiapublishing.com/historypress.com), various online retailers and numerous bookstores in Gettysburg.

The Battle of Gettysburg provides innumerable accounts of heroism, tragedy and sacrifice. And while most of these stories center upon those who served during the battle, not all of the sacrifices were made on the field of battle. To wit, for every soldier killed, wounded, captured or identified as missing in action as a result of the battle (totaling some 51,000 combined), there were multiple lives impacted on the home front. Like a jellyfish’s tentacles extending down into the sea, the pain and suffering stemming from battlefield losses reached deep and long among family, friends, and neighbors. Included among this group were the many women who had pledged their undying love to their betrothed as they marched off to war. The story of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt represents one such story. And though stories like this are as old as time, the added elements of this particular story – a secret engagement, a poignant last promise and a puzzling disappearance – make it one of the most remarkable and intriguing stories to ever stem from the battle.

Born into a prominent Lancaster, Pennsylvania family on September, 21, 1820, John Fulton Reynolds grew up a mere 55 miles from Gettysburg. During his formative years Reynolds received an excellent education, and by the summer of 1837 he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. At the time he was only 16 years old. After four years as a middling student, Reynolds graduated on July 1, 1841 ranking 26 out of 52. His favorite course had been horsemanship. In one letter home he boldly stated that “by the time I graduate I expect to be a great horseman.” Evidence indicates he lived up to that expectation. In any event, upon graduation he received his commission as a brevet second lieutenant in Company E, Third United States Artillery Regiment. With this, the nascent artillery officer and accomplished equestrian was on his way to what he surely thought would be bigger and better things.

Meanwhile, on April 1, 1836 the growing hamlet of Owego, New York saw the birth of Catherine Mary “Kate” Hewitt.” Ironically, Owego rested on the same line of longitude as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. And while Owego bordered upon the banks of the Susquehanna River, Lancaster was located very near the same river, albeit some 200 miles south of Owego. But unlike the privileged world of John Reynolds’s youth, Kate Hewitt and her older brother Benjamin found themselves leading the lives of orphans. Yet, like John, Kate managed to receive an excellent education. By her mid-twenties Kate Hewitt embarked on a life-changing sojourn to San Francisco, allegedly to work as a governess for a prominent and well-to-do family. However, within a few years young Ms. Hewitt found herself on her own. Left to fend for herself amidst the unbridled post-gold fever populace known to inhabit the San Francisco-Sacramento corridor, Kate resorted to the “world’s oldest profession ” in order to survive. And before long she also found herself embroiled in a scandalous affair. Kate’s reply to one newspaper reporter’s false accusations offered a staunch defense of herself. Having been accused of “ loving money better than the heart’s affections,” Kate published a rebuttal that spoke volumes with regard to her education, her character and unfortunate plight in life. In it she stated, “I do not assume the garb of hypocrisy, as thousands do, to palliate that which is wrong, but I do assert that however unfortunate I may be in my position in society, the purpose of my life and the impulses of my heart, may be no less generous and noble than those of my sex who have been better protected from the cruel wrongs I have been subjected to.” Ultimately, all of this prompted Kate to seek a rebirth if you will, or in other words, redemption. With her mind set to begin anew, she booked passage for herself and her so-called adopted “sister” to New York. Her sojourn began with a mid-July 1860 departure from San Francisco aboard the SS Golden Age bound for Panama (travel from San Francisco to New York, at the time, involved sailing to Panama, traveling across the isthmus by rail, and then to New York via another steamship).

As Kate struggled with life’s relentless challenges, John Reynolds was coming of age. Early in his army career Reynolds served quite admirably during the United States mid-1840s war with Mexico. His service during the war placed him in harm’s way on numerous occasions but somehow he survived unscathed. In fact, in each instance he proved his mettle, earning two brevet (honorary rank) promotions for his actions. After the war, Reynolds served in sundry duty stations ranging from coast to coast. Peace time promotions came slowly in the U.S. Army, yet Reynolds maintained his commitment to the life that fit him well. Interestingly, even in peacetime providence smiled on Reynolds. On one occasion, during December of 1853, he was on leave when a number of men in his regiment lost their lives in one of the greatest shipping tragedies of the 19th century, the sinking of the SS San Francisco. And just two years later, while transferring between duty stations on the west coast, he nearly lost his life when the ship he was on foundered on the treacherous Columbia River Bar and nearly sank. Reynolds indicated it was “all most [sic] a miracle we did not strike.” During the summer of 1860 Reynolds received orders requiring him to depart his west coast duty station in order to assume the duties of Commandant of Cadets at West Point. A confirmed bachelor at 39 years of age at the time, Reynolds boarded the SS Golden Age in San Francisco harbor, on July 21, 1860. Little did he know that in doing so he was about the meet the love of his life.

No one knows the details of their first meeting. Surely a novelist could conjure up a vivid portrayal of the moment. Did the gallant soldier assist the beautiful lady as she boarded the vessel? Or did they meet as the ship’s passengers scrambled for a parting view of the splendorous Golden Gate passage and the famed hills of San Francisco? We will likely never know. However, we do know what Kate Hewitt later conveyed to John Reynolds’s family that this voyage marked the occasion of their meeting. And judging from the ensuing events, we also know this is when they fell in love. Fittingly, the steamer that carried the couple on the last leg of their trip was named the SS North Star. Thus it seemed fate was calling both Kate Hewitt and John Reynolds to a new destiny. The question was, what might that destiny be?

Upon arriving in New York on August 13, 1861, the love-struck couple likely enjoyed a few more days of each other’s company. But soon enough duty called and Reynolds was off to West Point. Meanwhile, the nation was in a state of growing unrest and uncertainty as its “manifest destiny” continued to put strains on the ties that bonded the nation together. Thus, the duration of Reynolds’s assignment at his alma-mater seemed uncertain.

For Kate, there was no uncertainty. She remained committed to cleansing her soul. And sure enough, during the fall of 1861 she and her adopted sister entered Eden Hall Academy of the Sacred Heart, near Philadelphia. Over the ensuing seven months each proceeded to accomplish all that was necessary to enter into the Catholic faith – Baptism, First Communion and Confirmation. While enrolled, Kate impressed everyone and it was said she was “endowed with an honorable heart and an energy which renders her capable of overcoming all difficulties...” She would need this “energy” in the future. Having completed her conversion to Catholicism by July of 1861, it seemed as though only one thing remained for Kate – moving forward with her life alongside the man she loved. At the time, Kate likely felt that nothing could keep her and John apart. Sadly, there was one thing that could do just that – war.

Before John Reynolds marched off to war, he and Kate sealed their commitment to one another. The exact time and place of their engagement remains uncertain. A close analysis of the facts seems to indicate their engagement occurred before Kate Hewitt left Eden Hall. In fact, letters Kate sent to John before she departed Eden Hall bore the wax seal of his West Point class ring. If indeed he gave his ring to Kate as a sign of his commitment to marry, their engagement must have occurred before July of 1861 (when she left Eden Hall). Regardless, their engagement remained a secret. No surviving documentation indicates why this was so. One supposition points to religious differences as the source of John’s hesitancy to announce their plans to his family (he was Presbyterian). The recent discovery of Kate’s “experiences” in California reveals another possible reason for delaying the announcement. That said, the uncertainty over the exact date of their engagement and the fact that John and Kate kept it a secret are both overshadowed by one more thing - the fateful “last promise” Kate made to John.

War means danger. And with danger comes risk. Surely John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt recognized the inherent threat war posed to their relationship and their plans to marry. We do not know what sort of commitment, other than his promise to marry and the gift of his class ring, that John may have made to Kate. But if the measure of love can be determined by a single promise, Kate’s oath to John stands above all others. As John’s sister Jennie explained, “She had his consent to enter a religious life should she lose him.” Thus, Kate had promised John that if he were to be killed during the war she would give herself to the Lord. And with this poignant promise, the die was cast for one of the most tragic stories to emanate from the Battle of Gettysburg.

Prior to Gettysburg, during the first two years of the war, John Reynolds demonstrated his personal bravery on numerous occasions while also proving his capabilities as a leader of men. Over time, Reynolds progressed from commanding a brigade of soldiers, to a division and finally to corps command. And though he once suffered the unfortunate circumstance of being captured (he returned to duty two months later as a result of a prisoner exchange), somehow fate continued to smile on Reynolds as he avoided becoming a casualty of war. Along the way, Reynolds time and again risked his life during the heat of battle. For example, at Second Manassas during a critical moment as his forces sought to cover the Union army retreat, he grabbed the flag of one of his regiments and waved it furiously as he urged his blue-clad men forward, yelling “Now boys, give them the steel, charge bayonets, double quick !” In considering Reynolds’s good fortune, one of his men quipped, “he seemed to bear a charmed life.” Still, the question begged…when might Reynolds’s luck run out?

By the fall of 1862 the man who had begun the war as a lieutenant colonel of a U.S. infantry regiment (approximately 1,000 men) had been promoted to Major General of Volunteers and assumed command of the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac (approximately 10,000 men). By the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, Reynolds had been placed in command of an entire wing of the army (three corps, approximately 30,000 men). Moreover, during early June of 1863 Reynolds’s “star” reached its zenith when President Abraham Lincoln offered him command of the entire Union Army of the Potomac (approximately 100,000 men). But, in considering his concerns over potential meddling and interference to his command authority from the president and military authorities in Washington, D.C., Reynolds declined Lincoln’s offer. Ironically, as fate would have it, Reynolds’s decision increased the odds of the potential for his personal exposure to the enemy fire.

They say that truth is stranger than fiction. Sadly, the story of the ill-fated romance between John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt illustrates one such case. On the morning of July 1, 1863, as elements of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began an earnest approach on the modest southern Pennsylvania crossroads town known as Gettysburg, General John Reynolds’s wing command (First, Third and Eleventh Corps) represented the closest formative deterrent to their progress. And, as the stalwart Union cavalry troopers under courageous Union Army General John Buford did all that was humanly possible to delay the boys in butternut and gray, Reynolds’s command, with the First Corps in the lead, arrived to contest the disputed ground just west of Gettysburg.

Reynolds moved quickly to stymie the southern forces. As he deployed his infantry and positioned a battery of artillery, Reynolds soon found himself near the front lines. Here, his history of exposing himself to danger in the midst of battle worked against his safety. But the fact that the Confederates were threatening his native state, inching closer and closer to the very town of his birth and locations where his family resided, likely strengthened Reynolds’s resolve to defeat the invaders. And his experiences witnessing the failures in leadership in the Union army, failures that led to a growing series of defeats, probably contributed to his commitment to make certain he did everything in his power to assure the success of the troops under his command. In a sense his actions were visceral, yet they were equally understandable. As the rebel infantry pressed his men, the native Pennsylvanian urged elements of the famed “Iron Brigade” into action at Herbst Woods with the words, “Forward men, forward for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods!” A moment later, as he turned to look for reinforcements, a Confederate bullet found its mark. John Reynolds’s luck had finally run out.

Major General John Fulton Reynolds’s death on the morning of July 1, 1863 signified a tremendous blow to the Union Army. And it certainly amounted to a tragedy of untold proportion for his family. But his death also represented an inconceivable loss to someone else -- his fiancée Catherine Mary “Kate” Hewitt. Yet, no one associated with Reynolds knew anything of Kate, much less her engagement to him – but that was about to change. In carrying their fallen commander from the battlefield, members of his staff noticed a few things of importance. On August 4, 1863 Reynolds’s staff member Major William Riddle made note of these items in a letter to a fellow officer at army headquarters, “On the General’s little finger was that gold ring I spoke of bearing inside the words ‘Dear Kate,’ which he valued very highly.” Riddle continued, “He wore about his neck by a short silken string those two emblems of the Catholic faith – heart & cross …” As a Presbyterian, no one expected Reynolds to possess such items. And finally, as later conveyed by John’s family, his West Point class ring was missing and his valise contained two letters signed “Kate.” Clearly then, there had been a woman in John Reynolds’s life. However, beyond knowing her name and likely religion, the entire situation represented quite a mystery.

Back in Philadelphia, Kate Hewitt likely learned of her fiancé’s death through a local newspaper report as news of his death made the morning papers on July 2. Suddenly, all she lived for was gone. Meanwhile, her beloved’s remains were moved, under escort, from the battlefield to Union Bridge, Maryland where they were placed on a train for transit to Baltimore and then on to his sister’s home in Philadelphia, arriving just prior to 2 a.m. on July 3. With this, the family began to grieve over Reynolds’s remains. And they struggled with some degree of frustration and confusion over John’s missing class ring and the items found on his person (the cross and heart). Also, John’s valise contained the aforementioned letters signed by a woman named “Kate”, as well as some photos of a woman presumed to be Kate. But who was Kate? Soon the realization set in among his family that there was more, much more, to their fallen brother than they had ever known. And the more they learned, the more questions they had. Fortunately, the answers to their questions came soon enough with a knock on their door later that morning and the arrival of one Kate Hewitt.

Right away the family could see how devastated this mystery woman was. And to their credit, their hearts went out to her. As Kate Hewitt gazed upon the remains of her one time fiancé, her emotions came rushing to the surface. Once she composed herself, Kate proceeded to tell John Reynolds’s family of the love she had for their brother and how they had planned to announce their engagement to the family on July 8. But with his death on July 1 it was not to be. Kate went on to explain to the family how she and John had met on the ship coming from California. And finally, she told them of her poignant last promise to John. In the words of one of John’s sisters all of this hit them like a “thunder clap.” Be that as it may, John’s sisters quickly embraced Kate as one of their own, with John’s sister Jennie indicating, “We feel so for her, ‘tis like crushing the life out of her.” Lastly, with her mind set to enter into a religious life, Kate felt compelled to return John’s class ring to the family. John’s sister Ellie Reynolds captured the moment in a letter to her brother, naval officer William Reynolds, “She kissed it & put it on the glass plate [a portion of the coffin]. It was a great struggle.” Ellie also indicated that Kate asked only that the family “never let it be tainted by a disloyal hand. He was too true for that.”

True to her promise, Kate Hewitt began the process of entering into a religious life, choosing to do so with the Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland. This was the same group originally established as the Sisters of Charity by none other than Elizabeth Seton (later Saint Elizabeth Seton) in Emmitsburg in 1809. And much like Seton, a Catholic convert who had also struggled mightily with the loss of the man she loved, Kate had faced a life of constant challenges and adversity. Yet somehow, she managed to persevere.

As Kate began her journey with the Daughters of Charity, life was not through challenging her. Indeed, there would be challenges aplenty in her future and more adversity as well. There would also be some surprises. And with this, there would be many questions. Could she stay the course with the Daughters of Charity? And if not, what would become of her? Where would she live and how would she survive? Would she ever have another chance at love? Would the constant cough that had haunted her for years prove to be her undoing? And finally, what surprises might lay ahead for Kate Hewitt?

Though some portions of Kate’s remaining story have been known, key portions of her life, both before and after John Reynolds met his demise, remained shrouded in mystery for over a century and a half. In fact, her ultimate fate and true identity remained unknown until two years ago. Recent research conducted by this author and genealogist Mary Stanford Pitkin revealed previously unknown facets of her life as well as her true fate. As a result, we finally have a complete understanding of life and times of Kate Hewitt, one time fiancée of General John Reynolds. And in the end, Kate’s story is not only one of remarkable perseverance but one of triumph over adversity. In turn, the narrative surrounding the story of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt represents one of the most tragic stories connected to the Battle of Gettysburg.

Sources: Letter, Charles Veil to David McConaughy, April 7, 1864, John Reynolds Participants File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Letter, William Riddle to Lt. Bouvier, August 4, 1863, GNMP. Letter, Jennie Reynolds to William Reynolds, July 5, 1863, Reynolds Family Papers, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, PA (hereafter F & M). Letter, Ellie Reynolds to William Reynolds, July 5, 1863, F & M. Nichols, Edward J. Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of General John F. Reynolds . The Pennsylvania State Press, 1958. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day . Chapel Hill NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Riley, Michael A. “For God’s Sake, Forward!” General John Reynolds, USA . Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command . New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Hintz, Kalina Ingham. “’My Military Life as a Cadet Here…’: The West Point Years of Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds.” Gettysburg Magazine, Issue Number Twenty-Five. Harding, Jeff and Mary Stanford Pitkin. “Finding Kate.” Civil War Times, August 2020. Loski, Diana. “’For the Country’s Sake’: John Reynolds at Gettysburg. The Gettysburg Experience, April 2020. Harding, Jeffrey J. Gettysburg’s Lost Love Story – The Ill-Fated Romance of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt . Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022.

Born into a prominent Lancaster, Pennsylvania family on September, 21, 1820, John Fulton Reynolds grew up a mere 55 miles from Gettysburg. During his formative years Reynolds received an excellent education, and by the summer of 1837 he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. At the time he was only 16 years old. After four years as a middling student, Reynolds graduated on July 1, 1841 ranking 26 out of 52. His favorite course had been horsemanship. In one letter home he boldly stated that “by the time I graduate I expect to be a great horseman.” Evidence indicates he lived up to that expectation. In any event, upon graduation he received his commission as a brevet second lieutenant in Company E, Third United States Artillery Regiment. With this, the nascent artillery officer and accomplished equestrian was on his way to what he surely thought would be bigger and better things.

Meanwhile, on April 1, 1836 the growing hamlet of Owego, New York saw the birth of Catherine Mary “Kate” Hewitt.” Ironically, Owego rested on the same line of longitude as Lancaster, Pennsylvania. And while Owego bordered upon the banks of the Susquehanna River, Lancaster was located very near the same river, albeit some 200 miles south of Owego. But unlike the privileged world of John Reynolds’s youth, Kate Hewitt and her older brother Benjamin found themselves leading the lives of orphans. Yet, like John, Kate managed to receive an excellent education. By her mid-twenties Kate Hewitt embarked on a life-changing sojourn to San Francisco, allegedly to work as a governess for a prominent and well-to-do family. However, within a few years young Ms. Hewitt found herself on her own. Left to fend for herself amidst the unbridled post-gold fever populace known to inhabit the San Francisco-Sacramento corridor, Kate resorted to the “world’s oldest profession ” in order to survive. And before long she also found herself embroiled in a scandalous affair. Kate’s reply to one newspaper reporter’s false accusations offered a staunch defense of herself. Having been accused of “ loving money better than the heart’s affections,” Kate published a rebuttal that spoke volumes with regard to her education, her character and unfortunate plight in life. In it she stated, “I do not assume the garb of hypocrisy, as thousands do, to palliate that which is wrong, but I do assert that however unfortunate I may be in my position in society, the purpose of my life and the impulses of my heart, may be no less generous and noble than those of my sex who have been better protected from the cruel wrongs I have been subjected to.” Ultimately, all of this prompted Kate to seek a rebirth if you will, or in other words, redemption. With her mind set to begin anew, she booked passage for herself and her so-called adopted “sister” to New York. Her sojourn began with a mid-July 1860 departure from San Francisco aboard the SS Golden Age bound for Panama (travel from San Francisco to New York, at the time, involved sailing to Panama, traveling across the isthmus by rail, and then to New York via another steamship).

As Kate struggled with life’s relentless challenges, John Reynolds was coming of age. Early in his army career Reynolds served quite admirably during the United States mid-1840s war with Mexico. His service during the war placed him in harm’s way on numerous occasions but somehow he survived unscathed. In fact, in each instance he proved his mettle, earning two brevet (honorary rank) promotions for his actions. After the war, Reynolds served in sundry duty stations ranging from coast to coast. Peace time promotions came slowly in the U.S. Army, yet Reynolds maintained his commitment to the life that fit him well. Interestingly, even in peacetime providence smiled on Reynolds. On one occasion, during December of 1853, he was on leave when a number of men in his regiment lost their lives in one of the greatest shipping tragedies of the 19th century, the sinking of the SS San Francisco. And just two years later, while transferring between duty stations on the west coast, he nearly lost his life when the ship he was on foundered on the treacherous Columbia River Bar and nearly sank. Reynolds indicated it was “all most [sic] a miracle we did not strike.” During the summer of 1860 Reynolds received orders requiring him to depart his west coast duty station in order to assume the duties of Commandant of Cadets at West Point. A confirmed bachelor at 39 years of age at the time, Reynolds boarded the SS Golden Age in San Francisco harbor, on July 21, 1860. Little did he know that in doing so he was about the meet the love of his life.

No one knows the details of their first meeting. Surely a novelist could conjure up a vivid portrayal of the moment. Did the gallant soldier assist the beautiful lady as she boarded the vessel? Or did they meet as the ship’s passengers scrambled for a parting view of the splendorous Golden Gate passage and the famed hills of San Francisco? We will likely never know. However, we do know what Kate Hewitt later conveyed to John Reynolds’s family that this voyage marked the occasion of their meeting. And judging from the ensuing events, we also know this is when they fell in love. Fittingly, the steamer that carried the couple on the last leg of their trip was named the SS North Star. Thus it seemed fate was calling both Kate Hewitt and John Reynolds to a new destiny. The question was, what might that destiny be?

Upon arriving in New York on August 13, 1861, the love-struck couple likely enjoyed a few more days of each other’s company. But soon enough duty called and Reynolds was off to West Point. Meanwhile, the nation was in a state of growing unrest and uncertainty as its “manifest destiny” continued to put strains on the ties that bonded the nation together. Thus, the duration of Reynolds’s assignment at his alma-mater seemed uncertain.

For Kate, there was no uncertainty. She remained committed to cleansing her soul. And sure enough, during the fall of 1861 she and her adopted sister entered Eden Hall Academy of the Sacred Heart, near Philadelphia. Over the ensuing seven months each proceeded to accomplish all that was necessary to enter into the Catholic faith – Baptism, First Communion and Confirmation. While enrolled, Kate impressed everyone and it was said she was “endowed with an honorable heart and an energy which renders her capable of overcoming all difficulties...” She would need this “energy” in the future. Having completed her conversion to Catholicism by July of 1861, it seemed as though only one thing remained for Kate – moving forward with her life alongside the man she loved. At the time, Kate likely felt that nothing could keep her and John apart. Sadly, there was one thing that could do just that – war.

Before John Reynolds marched off to war, he and Kate sealed their commitment to one another. The exact time and place of their engagement remains uncertain. A close analysis of the facts seems to indicate their engagement occurred before Kate Hewitt left Eden Hall. In fact, letters Kate sent to John before she departed Eden Hall bore the wax seal of his West Point class ring. If indeed he gave his ring to Kate as a sign of his commitment to marry, their engagement must have occurred before July of 1861 (when she left Eden Hall). Regardless, their engagement remained a secret. No surviving documentation indicates why this was so. One supposition points to religious differences as the source of John’s hesitancy to announce their plans to his family (he was Presbyterian). The recent discovery of Kate’s “experiences” in California reveals another possible reason for delaying the announcement. That said, the uncertainty over the exact date of their engagement and the fact that John and Kate kept it a secret are both overshadowed by one more thing - the fateful “last promise” Kate made to John.

War means danger. And with danger comes risk. Surely John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt recognized the inherent threat war posed to their relationship and their plans to marry. We do not know what sort of commitment, other than his promise to marry and the gift of his class ring, that John may have made to Kate. But if the measure of love can be determined by a single promise, Kate’s oath to John stands above all others. As John’s sister Jennie explained, “She had his consent to enter a religious life should she lose him.” Thus, Kate had promised John that if he were to be killed during the war she would give herself to the Lord. And with this poignant promise, the die was cast for one of the most tragic stories to emanate from the Battle of Gettysburg.

Prior to Gettysburg, during the first two years of the war, John Reynolds demonstrated his personal bravery on numerous occasions while also proving his capabilities as a leader of men. Over time, Reynolds progressed from commanding a brigade of soldiers, to a division and finally to corps command. And though he once suffered the unfortunate circumstance of being captured (he returned to duty two months later as a result of a prisoner exchange), somehow fate continued to smile on Reynolds as he avoided becoming a casualty of war. Along the way, Reynolds time and again risked his life during the heat of battle. For example, at Second Manassas during a critical moment as his forces sought to cover the Union army retreat, he grabbed the flag of one of his regiments and waved it furiously as he urged his blue-clad men forward, yelling “Now boys, give them the steel, charge bayonets, double quick !” In considering Reynolds’s good fortune, one of his men quipped, “he seemed to bear a charmed life.” Still, the question begged…when might Reynolds’s luck run out?

By the fall of 1862 the man who had begun the war as a lieutenant colonel of a U.S. infantry regiment (approximately 1,000 men) had been promoted to Major General of Volunteers and assumed command of the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac (approximately 10,000 men). By the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, Reynolds had been placed in command of an entire wing of the army (three corps, approximately 30,000 men). Moreover, during early June of 1863 Reynolds’s “star” reached its zenith when President Abraham Lincoln offered him command of the entire Union Army of the Potomac (approximately 100,000 men). But, in considering his concerns over potential meddling and interference to his command authority from the president and military authorities in Washington, D.C., Reynolds declined Lincoln’s offer. Ironically, as fate would have it, Reynolds’s decision increased the odds of the potential for his personal exposure to the enemy fire.

They say that truth is stranger than fiction. Sadly, the story of the ill-fated romance between John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt illustrates one such case. On the morning of July 1, 1863, as elements of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began an earnest approach on the modest southern Pennsylvania crossroads town known as Gettysburg, General John Reynolds’s wing command (First, Third and Eleventh Corps) represented the closest formative deterrent to their progress. And, as the stalwart Union cavalry troopers under courageous Union Army General John Buford did all that was humanly possible to delay the boys in butternut and gray, Reynolds’s command, with the First Corps in the lead, arrived to contest the disputed ground just west of Gettysburg.

Reynolds moved quickly to stymie the southern forces. As he deployed his infantry and positioned a battery of artillery, Reynolds soon found himself near the front lines. Here, his history of exposing himself to danger in the midst of battle worked against his safety. But the fact that the Confederates were threatening his native state, inching closer and closer to the very town of his birth and locations where his family resided, likely strengthened Reynolds’s resolve to defeat the invaders. And his experiences witnessing the failures in leadership in the Union army, failures that led to a growing series of defeats, probably contributed to his commitment to make certain he did everything in his power to assure the success of the troops under his command. In a sense his actions were visceral, yet they were equally understandable. As the rebel infantry pressed his men, the native Pennsylvanian urged elements of the famed “Iron Brigade” into action at Herbst Woods with the words, “Forward men, forward for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods!” A moment later, as he turned to look for reinforcements, a Confederate bullet found its mark. John Reynolds’s luck had finally run out.

Major General John Fulton Reynolds’s death on the morning of July 1, 1863 signified a tremendous blow to the Union Army. And it certainly amounted to a tragedy of untold proportion for his family. But his death also represented an inconceivable loss to someone else -- his fiancée Catherine Mary “Kate” Hewitt. Yet, no one associated with Reynolds knew anything of Kate, much less her engagement to him – but that was about to change. In carrying their fallen commander from the battlefield, members of his staff noticed a few things of importance. On August 4, 1863 Reynolds’s staff member Major William Riddle made note of these items in a letter to a fellow officer at army headquarters, “On the General’s little finger was that gold ring I spoke of bearing inside the words ‘Dear Kate,’ which he valued very highly.” Riddle continued, “He wore about his neck by a short silken string those two emblems of the Catholic faith – heart & cross …” As a Presbyterian, no one expected Reynolds to possess such items. And finally, as later conveyed by John’s family, his West Point class ring was missing and his valise contained two letters signed “Kate.” Clearly then, there had been a woman in John Reynolds’s life. However, beyond knowing her name and likely religion, the entire situation represented quite a mystery.

Back in Philadelphia, Kate Hewitt likely learned of her fiancé’s death through a local newspaper report as news of his death made the morning papers on July 2. Suddenly, all she lived for was gone. Meanwhile, her beloved’s remains were moved, under escort, from the battlefield to Union Bridge, Maryland where they were placed on a train for transit to Baltimore and then on to his sister’s home in Philadelphia, arriving just prior to 2 a.m. on July 3. With this, the family began to grieve over Reynolds’s remains. And they struggled with some degree of frustration and confusion over John’s missing class ring and the items found on his person (the cross and heart). Also, John’s valise contained the aforementioned letters signed by a woman named “Kate”, as well as some photos of a woman presumed to be Kate. But who was Kate? Soon the realization set in among his family that there was more, much more, to their fallen brother than they had ever known. And the more they learned, the more questions they had. Fortunately, the answers to their questions came soon enough with a knock on their door later that morning and the arrival of one Kate Hewitt.

Right away the family could see how devastated this mystery woman was. And to their credit, their hearts went out to her. As Kate Hewitt gazed upon the remains of her one time fiancé, her emotions came rushing to the surface. Once she composed herself, Kate proceeded to tell John Reynolds’s family of the love she had for their brother and how they had planned to announce their engagement to the family on July 8. But with his death on July 1 it was not to be. Kate went on to explain to the family how she and John had met on the ship coming from California. And finally, she told them of her poignant last promise to John. In the words of one of John’s sisters all of this hit them like a “thunder clap.” Be that as it may, John’s sisters quickly embraced Kate as one of their own, with John’s sister Jennie indicating, “We feel so for her, ‘tis like crushing the life out of her.” Lastly, with her mind set to enter into a religious life, Kate felt compelled to return John’s class ring to the family. John’s sister Ellie Reynolds captured the moment in a letter to her brother, naval officer William Reynolds, “She kissed it & put it on the glass plate [a portion of the coffin]. It was a great struggle.” Ellie also indicated that Kate asked only that the family “never let it be tainted by a disloyal hand. He was too true for that.”

True to her promise, Kate Hewitt began the process of entering into a religious life, choosing to do so with the Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland. This was the same group originally established as the Sisters of Charity by none other than Elizabeth Seton (later Saint Elizabeth Seton) in Emmitsburg in 1809. And much like Seton, a Catholic convert who had also struggled mightily with the loss of the man she loved, Kate had faced a life of constant challenges and adversity. Yet somehow, she managed to persevere.

As Kate began her journey with the Daughters of Charity, life was not through challenging her. Indeed, there would be challenges aplenty in her future and more adversity as well. There would also be some surprises. And with this, there would be many questions. Could she stay the course with the Daughters of Charity? And if not, what would become of her? Where would she live and how would she survive? Would she ever have another chance at love? Would the constant cough that had haunted her for years prove to be her undoing? And finally, what surprises might lay ahead for Kate Hewitt?

Though some portions of Kate’s remaining story have been known, key portions of her life, both before and after John Reynolds met his demise, remained shrouded in mystery for over a century and a half. In fact, her ultimate fate and true identity remained unknown until two years ago. Recent research conducted by this author and genealogist Mary Stanford Pitkin revealed previously unknown facets of her life as well as her true fate. As a result, we finally have a complete understanding of life and times of Kate Hewitt, one time fiancée of General John Reynolds. And in the end, Kate’s story is not only one of remarkable perseverance but one of triumph over adversity. In turn, the narrative surrounding the story of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt represents one of the most tragic stories connected to the Battle of Gettysburg.

Sources: Letter, Charles Veil to David McConaughy, April 7, 1864, John Reynolds Participants File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Letter, William Riddle to Lt. Bouvier, August 4, 1863, GNMP. Letter, Jennie Reynolds to William Reynolds, July 5, 1863, Reynolds Family Papers, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, PA (hereafter F & M). Letter, Ellie Reynolds to William Reynolds, July 5, 1863, F & M. Nichols, Edward J. Toward Gettysburg: A Biography of General John F. Reynolds . The Pennsylvania State Press, 1958. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day . Chapel Hill NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Riley, Michael A. “For God’s Sake, Forward!” General John Reynolds, USA . Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in Command . New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Hintz, Kalina Ingham. “’My Military Life as a Cadet Here…’: The West Point Years of Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds.” Gettysburg Magazine, Issue Number Twenty-Five. Harding, Jeff and Mary Stanford Pitkin. “Finding Kate.” Civil War Times, August 2020. Loski, Diana. “’For the Country’s Sake’: John Reynolds at Gettysburg. The Gettysburg Experience, April 2020. Harding, Jeffrey J. Gettysburg’s Lost Love Story – The Ill-Fated Romance of General John Reynolds and Kate Hewitt . Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022.