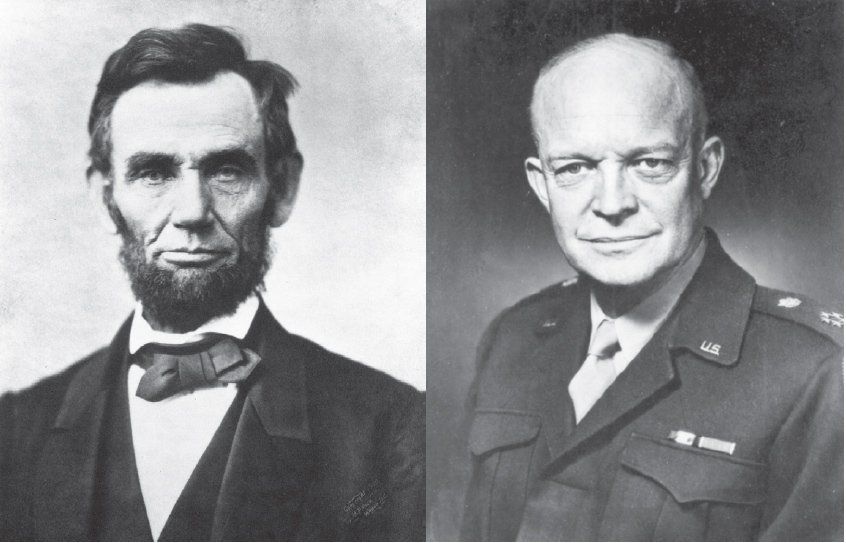

Lincoln & Ike: 5 Shared Leadership Traits

by Diana Loski

Two of our greatest Presidents, Abraham Lincoln and Dwight D. Eisenhower, are forever tied to the town of Gettysburg. They grew up in different centuries and had few similarities in their childhoods – and they faced very real but different dangers throughout their tenures as world leaders. Yet, a careful look at the way they led and helped shape future generations will reveal definite connections. Here are five leadership traits practiced by both men.

1. Both Lincoln and Eisenhower knew their history, and applied that knowledge for their (and the people’s) benefit. When Lincoln first ran for office in the early days of Illinois statehood, one prairie denizen who first noticed the gangly, ruddy Lincoln, remarked, “Can’t the party raise any better material than that?” Then he heard Lincoln speak and marveled at his logic and intelligence. The listener said that “Lincoln filled him with amazement; that he knew more than all the other candidates put together.”1

Lincoln understood the Constitution to the last detail. Many of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were still living when he was a youth. The last signer, James Madison, died in 1836, when Lincoln was 27 years old. The nation was still in its infancy, with many issues unresolved or misunderstood. Lincoln’s thorough grasp of what history existed at the time helped him to become the strong leader that was desperately needed during the Civil War.2

Dwight D. Eisenhower also applied what history recorded for his time. He missed fighting in Europe during World War I; he was instead placed in command at Camp Colt in Gettysburg: a training ground for tank warfare in 1918. When he was made Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II, he had learned what did not work during the last conflict. The Battle of the Somme, for example, began on July 1, 1916 and lasted many months; it took over one million casualties with no gain for the Allies. It was a complete waste of human lives, which Eisenhower detested. He had learned from those who had survived that England had been too eager to get to the front. General Douglas Haig, a less-than-stellar commander, had thrown untrained troops at the foe. Moreover, he had not planned for a longer, sustained battle, making only rudimentary trenches. In Britain, since so many had signed up to fight, untrained workers filled the factories that made the weaponry. As a result, nearly half of the allied artillery shells were duds. The Germans, on the other hand, had planned to stay and made their trenches more livable with furniture, drywall, and even electricity. With German weaponry, they had also prepared in advance.3

In 1942, as Americans and their allies demanded immediate action in Europe, Ike knew he did not want another Battle of the Somme. Ike related a real concern “of securing practical battlefield experience…before the whole of [the Army] should finally be thrown into a life-and-death struggle.” Knowing the resolve of Hitler and the Wehrmacht

, he knew the only way to defeat the Nazis was with training and determination. He shrugged off the naysayers and fully trained his troops before engaging them. He worked on an elaborate deception scheme to fool Hitler as to the place and time of the Allied attack on the French coast. It took two years before the Allies were prepared for the D-Day invasion, but Ike’s knowledge of history made the fight, and ultimately the war, victorious for the Allies.4

2. Both men were industrious and perpetual learners. From his childhood, Abraham Lincoln was insatiably curious and hard-working. The chronicles of his proclivity with an axe and the two-mile-long walk to and from school are well documented. He learned early in his life that working with his brain was far more satisfying than physical labor. He enjoyed study, and in spite of a rudimentary education, he was highly intelligent. He read certain books many times, including The Bible, Aesop’s Fables, and Pilgrim’s Progress. He memorized poetry and was familiar with Shakespeare’s multitude of plays. Even at age 8, he was a prolific reader and easily maintained what he learned. Many who knew Lincoln from his youth marveled at his memory and were astonished how easily he grasped complex subjects. A childhood acquaintance recalled that Lincoln “had the best memory of any person I ever knew.”5

One day before he was President, Lincoln stopped in at the local telegraph office. He asked Charles Tinker, the operator, if Tinker would explain to him how the telegraph worked. Tinker later said, “I proceeded to show [Mr. Lincoln] the working of the telegraph, explained the battery and its connection to the instruments, and the wires leading thence out of the window and away to the world without. I was encouraged by the readiness with which he comprehended it all.” Lincoln told him, “ How simple it is when you know it all!”6

Eisenhower was also industrious and studious. As a boy, he learned the satisfaction of earning money for his work. His mother allowed her sons to grow their own fruits and vegetables in the garden and they could sell the excess. “I chose to grow sweet corn and cucumbers,” Ike remembered. “I had made inquiries and decided that these were the most popular.”7

Since harvest time was only part of the year, Ike learned from his mother how to make tamales. He sold them door-to-door as “ a good off-season sales idea.” As for the leftovers, he “consumed them without strain.”8

Ike studied history as a youth, sometimes to excess. Because he preferred reading to his chores, his mother “took my volumes of history away and locked them in the closet.” The ever-industrious youth nevertheless found the key and read his books when she went to town.9

Years after Ike had married and was serving in Panama, his mentor Fox Conner helped the future leader to rekindle that love of history and learning. Conner encouraged Ike to read the memoirs of U.S. Grant and Sherman, and to study more in-depth accounts of the Civil War. As Ike studied these accounts, he saw the pattern of great leaders and their inspired tactics. Not surprisingly, when Eisenhower attended command school, he graduated first in his class, in 1926.10

3. Both genuinely liked people, and were compassionate men. Perhaps Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is so highly praised because of the depth of his compassion in the brief speech. Lincoln was always kind to people. Frederick Douglass said, “no man who knew Abraham Lincoln could hate him.”11

Lincoln was especially kind to the elderly and to children. One woman in later years remarked that when she was a girl, Lincoln worked on the ferry, and often displayed “a gentle manner with the children, while the other hand employed there was very brusque.” Lincoln’s compassion continued all his life, including when he was President.12

Lincoln pardoned hundreds of offenders, both military and civilian, during the course of his Presidency – something that irked his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. “Lincoln was for giving a wayward subordinate seventy times seven chances to repair his errors,” remembered one White House associate.13

One likely reason for his compassion for others was due to the many losses he experienced in his life. He lost his mother when he was just nine years old, his only sister ten years later, and two of his four sons preceded him in death.

Eisenhower also experienced a tremendous loss when his firstborn son died at age three of scarlet fever. “This was the greatest disappointment and disaster in my life,” he remembered decades later, “the one I have never been able to forget completely.”14

This memory served the Supreme Allied Commander in preserving lives. Ike also spent time with the enlisted men and was visible before many engagements. Just before crossing the Rhine, near the end of the war, Ike visited some of the troops. He noticed a young soldier who “was silent and depressed.” Ike asked the soldier how he was feeling. The young man responded, “I’m awful nervous. I was wounded two months ago and just got back from the hospital yesterday.” He added, “I don’t feel so good.” The general responded that he was nervous too, and invited the soldier to walk with him. On the stroll, Ike told the enlisted boy that “we’ve planned this attack for a long time, and we’ve got the planes, the guns, and airborne troops we can use to smash the Germans.” He added that the war was close to ending and the Allies would finish it. The soldier relaxed, said he felt better, and went his way.15

4. Both were willing to listen to the ideas of others, including subordinates. Lincoln’s cabinet was made of a group of men of high ambition. They spoke their minds – something Lincoln wanted them to do. When he intended to create The Emancipation Proclamation, his entire cabinet was against it. Lincoln remained calm as he listened to their reasons – one of which was it would appear an act of desperation, “our last shriek”, as the Union had yet to win a battle in 1862. Secretary of State William Henry Seward said to at least wait until a victory could be won before announcing it. Lincoln agreed.16

Lincoln appeared to take his time to make a decision. He thought carefully, and as long as time would allow. Once he made his decision, he stuck to it. Like any great leader, he took the blame if the decision proved disastrous; he shared the accolades in success.17

Ike followed the same process as Supreme Allied Commander. In the long planning of the Normandy Invasion, Ike frequently consulted with statisticians and challenged their findings to thwart catastrophe. Soon, the stress of keeping Operation Overlord a secret began to wear away his nerves. When a severe storm over the English Channel threatened the assault, Ike postponed the launch for 24 hours. He then consulted with the other generals. Most, like England’s Bernard Montgomery, wanted to go. Admiral Ramsay wanted to go but had misgivings. Air Chief Marshall Tedder wanted to postpone, naturally concerned for the new Airborne units. Ike knew a long postponement would affect morale, and, even worse, “secrecy would be lost.” After learning from their meteorologists that there was a small window the following day of “relatively good weather”, Ike decided to go ahead with the invasion. He remembered that “there was a general brightening of faces

” with his decision. Before the 101st Airborne units took off, Ike visited them. There were tears in his eyes as he watched them fly across the Channel.18

Like Lincoln, Eisenhower allowed the accolades to flow to all when there was success. He shouldered the blame alone.

5. Both were honest. In a leader, trust is the most important attribute. Both Abraham Lincoln and Dwight D. Eisenhower were scrupulously honest.

In practicing law, Lincoln never charged a high fee and was immensely popular. William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner in Springfield, remembered a murder case where Lincoln defended the accused. The youth’s mother, Hannah Armstrong, was a personal friend who had little money. Lincoln “secured the acquittal…one of the most gratifying triumphs in his career as a lawyer.” When Hannah asked what payment she was to give, Lincoln replied, “Why, Hannah, I shan’t charge you a cent.” He never overcharged clients and while other attorneys were becoming wealthy, Lincoln “cared nothing

” for wealth or speculation.19

While President, Lincoln was furious when he learned of his wife’s secret (and extravagant) spending during the war. It needed approval by Congress, which they were reluctant to bestow. When he saw the bills that amounted to thousands of dollars, he determined to pay them out of his own pocket.20

Ida Eisenhower, Ike’s mother, often engaged in heart-to-heart talks with her middle son. She once told him, “He that conquereth his own soul is greater than he who taketh a city.” The future general and President later recalled that her advice was one of the most valuable of his life.21

A rarely remembered incident of Eisenhower’s tenure in the closing days of his Presidency demonstrates his complete honesty. During the 1950s, the USA had an uneasy friendship with the Soviet Union, led at the time by Nikita Khrushchev. Both nations spied on each other, and in 1960, one of the American spy planes was shot down over Soviet air space. Ike related to his Gettysburg pastor, Bob MacAskill, that the Soviets had the U.S. pilot “kicking and screaming.” Ike’s cabinet wanted to disavow any knowledge of the plane, but Ike knew better. He said, “Of course we knew. And not only would most of the American people know it was a lie, but Khrushchev would know I lied if I were to say that.” The President did not trust his people to tell the truth, so he personally went before the press corps, and admitted that he knew about the spy plane.22

The incident caused political fallout, and sealed the full onset of the Cold War. It resembled the press excoriating Mary Lincoln for her lavish spending during the Civil War. Honesty often brings temporary consequences, but moral courage always demonstrates the epitome of true leadership.

These two Presidents entered the arena just as they were needed. Their attributes are worthy, still, of study and emulation.

Sources: Baker, Jean H. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography . New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008 (reprint, first published in 1987). Douglass, Frederick. “Cooper Union Speech, June 1, 1865”, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Eisenhower, Dwight D. At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends . National Park Service: Eastern Acorn Press, 1998 (reprint, first published in 1967). Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe . New York: Doubleday & Company, 1948. Gilbert, Martin. The Somme: Heroism and Horror in the First World War . New York: Owl Books, Henry Holt & Company, LLC, 2006. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Herndon, William H. & Jesse W. Weik. Herndon’s Lincoln . Urbana and Chicago: Knox College Lincoln Studies Center, University of Illinois Press, 2006 (originally published in 1889). Holl, Jack M. The Religious Journey of Dwight D. Eisenhower . Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2021. Loski, Diana. Interview with Bob MacAskill, April, 1998. Oates, Stephen B. With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln . New York: HarperCollins, 1994 (reprint, originally published in 1977). Phillips Donald T. Lincoln on Leadership for Today . Boston & New York: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. Warren, Louis A. Lincoln’s Youth . Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2002 (reprint, originally published in 1959).

End Notes:

1. Herndon, pp. 87-88.

2. Madison was the last signer of The Constitution. The last

surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll, died four years before Madison, in 1832.

3. Gilbert, pp. 243-246. The Battle of Verdun, which engaged the Germans vs. the French troops also lasted for several months in 1916, equally took a mil- lion casualties.

4. Eisenhower, Crusade

, p. 40.

5. Warren, pp. 45-46, 80.

6. Phillips, p. 44.

7. Eisenhower, At Ease

, p. 70.

8. Ibid., p. 71.

9. Ibid., p. 39.

10. Holl, pp. 83, 87.

11. Douglass, Cooper Union Speech, LC.

12. Warren, p. 145.

13. Goodwin, p. 560.

14. Eisenhower, At Ease

, p. 181.

15. Eisenhower, Crusade

, p. 389.

16. Oates, p. 311.

17. Phillips, p. 109.

18. Eisenhower, Crusade, pp. 239, 249-50, 252.

19. Herndon, pp. 215, 221-222.

20. Baker, p. 189.

21. Eisenhower, At Ease

, p. 52.

22. Loski, Interview with Bob MacAskill, April 1998.