General John C. Robinson: "One of the Most Illustrious"

by Diana Loski

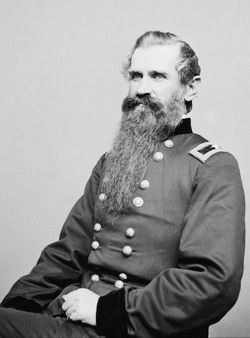

John C. Robinson

(Library of Congress)

John Cleveland Robinson was born to be a soldier. He entered the world on April 10, 1817, the penultimate son of the Honorable Tracy Robinson and his wife, the former Sarah Cleveland. The family came from Connecticut, but Tracy, a doctor, postmaster, and judge, decided to move his young family to Binghamton, New York when it was “only a squad of cabins”. John was the fourth of five siblings; his sister, Ambrosia and his brothers Erasmus and Sidney had been born in Connecticut. Only John and his younger brother, Charles, were born in Binghamton.2

Due to his father’s political connections, John was able to secure an appointment to West Point in 1835, when he was just eighteen years old. He did not graduate, as he was dismissed from the Academy during his third year for a violation of the rules. For two years, John studied law. Before the year 1839 had ended, however, Robinson was back in the army, as a lieutenant of the 5th U.S. Infantry. He served in the War with Mexico under General Zachary Taylor. He participated in the Battles of Palo Alto, Monterrey, and Mexico City.3

After the war, Robinson served as the army quartermaster. He married his long-term sweetheart, Sarah Maria Pease, whose family also came to Binghamton from Connecticut. Seven children were born to the couple over the years, although only three lived to adulthood.4

Robinson remained with the Federal army in the years leading up to the Civil War. He fought against Native American uprisings in Texas and Florida, and was part of the Utah Expedition. He was serving as the commander of the garrison at Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, when war began in the spring of 1861.5

Robinson’s early penchant for leadership was made evident during a Confederate civilian revolt shortly after Fort Sumter fell in April 1861. As Maryland, a border state, was deeply divided, riots soon erupted in Baltimore and Fort McHenry was threatened. To thwart the rebellion, Robinson “made them believe that a steamer which had put into port with coal had brought him reinforcements. As a part of his ruse, he pitched all the tents he had.” His actions saved the fort.6

Robinson made the journey to Michigan in the early days of the war to recruit soldiers. He raised the 1st Michigan Infantry and was elected its colonel. As the unit was recruited for three months, Robinson and his men spent most of that time in Maryland, guarding the railroads. He was promoted to brigade command at Newport News, Virginia in May 1862 and sent to the Army of the Potomac. He fought in the Peninsula Campaign with Philip Kearny’s Third Corps and suffered a head wound at the Battle of Richmond.7

Robinson fought at Second Manassas and Fredericksburg but escaped injury. He was promoted to division command in the Union First Corps before the Battle of Chancellorsville. He was “lightly engaged ” at Chancellorsville, but that would change with the next fight at Gettysburg.8

As part of the First Corps, Robinson’s Second Division comprised two brigades led by Brigadier Generals Gabriel Paul and Henry Baxter, with men from various states. The regiments included the 16th Maine, the 12th and 13th Massachusetts, the 11th, 88th, 90th and 107th Pennsylvania, and the 83rd, 94th, 97th, and 104th New York Infantries. As they arrived on Oak Ridge west of the town, the battle had already expanded with advancing, determined Confederate forces attempting to reach Gettysburg. General Robinson’s men formed the Union’s right flank that day, with the 13th Massachusetts as the end of the line. Robinson, on horseback, ordered his men to entrench. He intended for their position to hold.9

Robinson’s Division fired upon the North Carolinians from General Iverson’s brigade, and many of the men in gray fell, unable to dislodge the men on Oak Ridge. More of the Carolinians from part of Junius Daniel’s and all of Stephen D. Ramseur’s brigades pressed forward, wounding General Paul and killing many from his brigade. General Baxter’s men fired their muskets until they depleted their ammunition – and they too had taken heavy casualties. Unable to defend the line, most of Baxter’s troops promptly retreated and did not return, leaving only Paul’s brigade and possibly the 97th New York from Baxter’s brigade to fend off the advancing Confederates. Twice General Robinson’s horses were shot from under him.10

The arrival of the Union Eleventh Corps in the fields below them, and north of town, protected Robinson’s line for a time. When the Union forces there were broken, however, Robinson received orders to retreat. Robinson ordered the 16th Maine to cover the withdrawal. The men from Maine obeyed, and most of them were captured.

In spite of their losses and the loss of the position, Robinson’s men had held firmly against a much larger foe. Though his superiors had been found lacking that day, Robinson received praise for his determined stance.

His temerity would be called upon again in 1864.

With the promotion of Ulysses S. Grant in early 1864 over all Union armies, Grant decided that General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was where the Federals should focus. Grant began his Overland Campaign in his attempt to take Richmond in the spring.

The staggering losses at Gettysburg necessitated converging of the army. The First Corps no longer existed, and its surviving troops and their generals were used to bolster the Union Fifth Corps. General Robinson commanded a division in that corps.

At the Battle of Spotsylvania on May 8, 1864, General Robinson ordered a charge on the Confederate breastworks in Laurel Hill, Virginia. While leading the charge, Robinson was shot, resulting in a severe wound in his left knee. Carried to the rear, the surgeon told him that amputation was necessary to save his life.11

The amputation ended Robinson’s career on the battlefield. Once he recovered, Robinson was placed in command in the Military District of New York. He was in New York when Lee surrendered at Appomattox.12

Although the general’s Civil War career ended, his service to the nation would continue throughout the remainder of his life.

Robinson served the slowly mending country during Reconstruction. He commanded the Freemen Bureau in North Carolina in 1866, was over the Department of the South in 1867, and the Department of the Lakes in 1868. He retired from the U.S. Army in 1869 due to disability. He served as Lieutenant Governor of New York under Governor Dix during the Grant Administration. He was then elected governor of New York from 1872 through 1874.13

Robinson’s old wound from the Battle of Richmond began to play havoc with his failing eyesight. Shortly after returning to Binghamton as a civilian and former statesman, Robinson was elected to a post that for him was the greatest honor of all. He was elected as Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, the national organization of Union army veterans. He served in that capacity for two terms, enjoying the many reunions and commemorations among those who served in the recent war. As his sight continued to fail, he was then elected as President of the Society of the Army of the Potomac. 14

In 1892, John Robinson lost his wife of fifty years. By the following hear, he was completely blind, an ailment that had been worsening since his wounding at Richmond. In spite of these losses, coupled with his amputated leg, “the vitality displayed by the old veteran was most remarkable”.15

There was yet another honor for the courageous general. In 1894, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his gallantry at the Battle of Laurel Hill, at Spotsylvania, which had cost him his left leg.16

In his declining years, General Robinson enjoyed the companionship of his grown children, his grandchildren, and his many friends among the veterans and townspeople of Binghamton. He suffered from Bright’s Disease, a degenerative kidney ailment. It was from this disease that he died, two months shy of his eightieth birthday, on February 18, 1897. His passing was greatly lamented. One writer claimed that Robinson “has one of the most illustrious records of any of Broome County’s sons.” He was buried with military honors in Spring Forest Cemetery.17

Two decades later, as America’s sons and daughters rushed off to fight in World War I, there was one last remembrance given to the old veteran from Binghamton. On Oak Ridge, just west of the town of Gettysburg, a portrait statue was unveiled of the devoted Union general. John Cleveland Robinson stands once again as commander of his division, still determined to hold the line of blue on Gettysburg’s first day.

This time he’s there to stay.

The Robinson Portrait Statue,

Oak Ridge, Gettysburg

Sources: Ancestry.com/John Cleveland Robinson Family Tree. The Buffalo Commercial, 13 Feb., 1897. The Buffalo Times, 22 Feb., 1897. Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography

. Volume V. New York: 1888. The Herald Statesman, 19 Feb., 1897. The New York Times, 19 Feb. 1897. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day

. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. General John C. Robinson Memorial Statue, Gettysburg, PA. Warner, Ezra T. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders

. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1964. Historic Newspapers found at newspapers.com.

End Notes:

1. Warner, p. 407.

2. John C. Robinson Family Tree,

Ancestry.com.

3. Drake, p. 305.

4. Robinson Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

5. New York Times, 19 Feb., 1897.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Warner, p. 408.

9. Pfanz p. 181.

10. Ibid., pp. 181-182.

11. Drake, p. 305. The John Robinson

Memorial, Gettysburg.

12. Drake, p. 305.

13. The Herald Statesman, 19 Feb., 1897.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16.John Robinson Memorial, Gettysburg.

17.The Buffalo Commercial, 13 Feb., 1897. The Buffalo Times, 22 Feb., 1897.