Our Civil War Songs

by Diana Loski

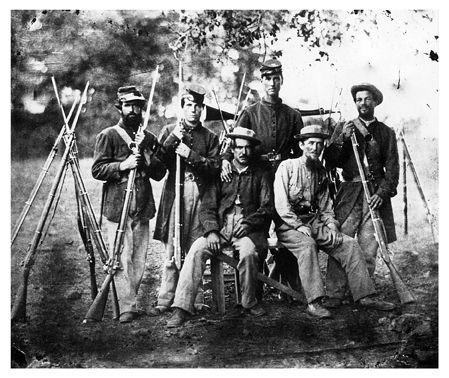

Confederate soldiers, 1861

(Library of Congress)

Music has often provided a significant lift to special times, and the holidays are no exception. In joyous times or difficult ones, music is a boon to most societies and the individuals within them.

During the Civil War, music played a key role in a soldier’s life. The conflict inspired many poets and songwriters from both sides of the Mason Dixon Line.

When the war ended, these songs were put away for a time, as survivors longed to forget, along with their folded battle flags and war-torn uniforms. During the reunions that ensued, however, the songs were resurrected once again, bringing with them the memories of the days and comrades that were no more.

The songs brought back memories of camping in snow and heat, stacking arms by the fire, choking on dust-covered roads during long, weary marches, or burying their dead by moonlight. The memories evoked by these songs are now long quieted.

Most of the songs were partisan, favoring either the Union or the Confederacy. A few, though, appealed to both sides. The song All Quiet on the Potomac , for example, struck a chord with both the North and the South, as both sides camped along that great river that divided Virginia from the North. Other tunes, such as The Girl I Left Behind Me, Lorena, and Kathleen Mavourneen were haunting tunes of leaving behind their loved ones on both sides. Another favorite was Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground – which was sung as late as the Last Reunion at Gettysburg by the veterans, in 1938.

Soldiers often would “war” in song when the battlefield did not occupy them otherwise, and as the campgrounds were within a short distance from one another. Strains of Dixie were met by loud choruses of Glory Hallelujah across the picket lines in a contest to see which side could drown out the other.1

Dixie was undoubtedly the Confederate favorite. Ironically, it was written by Dan Emmett and Albert Pike and was sung in the antebellum years in New England and New York City music halls. At the outbreak of the conflict, Dixie was played at Jefferson Davis’s inauguration in Montgomery, Alabama. According to many soldiers’ accounts, General Pickett ordered the song played before his division embarked on their famous charge at Gettysburg.

Other Confederate favorites included The Bonnie Blue Flag, written by a Scottish actor, and When Johnnie Comes Marching Home, written by Louis Lambert.

The Union, too, enjoyed songs that were exclusively theirs. The favorite Glory Hallelujah or Battle Hymn of the Republic , originated as John Brown’s Body. It was changed early in the war, when in 1862, Julia Ward Howe heard marching soldiers singing the lyrics about John Brown’s body lying moldering in the grave, and she was horrified. She wrote much better lyrics, comparing the war to a crusade for righteousness. Soldiers sang both versions during the war. The song, at least the latter rendition, remains popular today.2

Along with the Battle Hymn , other favorite Union songs were Battle Cry of Freedom , written by patriotic Union composer George Root. Introduced in New York City at the start of the war in 1861, the song was instantly popular.

During the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, a brigade of Pennsylvania soldiers became separated from the rest of the Union troops and were surprised by a contingent of Confederates. Amid the daunting rebel yells, the men began to fall back in disorder. Suddenly, one of the soldiers began to sing Battle Cry of Freedom. The chorus caused the men to rally and they pushed back the Confederate force.3

The power of song was demonstrated many times during the war, inspiring the combatants from both sides of the conflict.

The soldiers’ good humor was sometimes made evident in song. Sometimes they compromised, or made-up versions of their own, such as this unique rendition of a well-known nursery rhyme:

Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow,

Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom!

And everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go,

Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom!4

When some of the troops from Buford’s Division entered Gettysburg, a group of girls from the town were so overjoyed to see them, that they gathered at the corner of Washington and High Streets and sang to them as the cavalry rode toward their positions. The music was a boon to the men, as they had been in the hostile South for so long. “Their countenances brightened,” remembered one, “and we received their thanks and cheers.”5

Music provided a needed solace to the wounded. On the night of July 2, 1863, a full moon hung over the Gettysburg battlefield where thousands were wounded, and many of them were dying. One Georgia soldier remembered that “one of our soldiers out between the lines, I think it was one of General McLaws’s men, began to sing. He was probably a boy raised in some religious home in the South, where the good old hymns were standard music…I have never heard music like that…in the still air and moonlight of that night, there were hundreds, perhaps thousands of desperately wounded men lying on the ground within easy hearing of the singer, whose fine voice rang out like a flute and echoed up and down the valley…There was a marked silence that could come only from attention. And I think the Federal line could hear him as well as ourselves. One of the hymns he sang was this familiar one:

“Come, ye disconsolate,

wherever ye languish,

Come to the mercy seat,

fervently kneel,

Hither bring your wounded hearts, here tell your anguish,

Earth hath no sorrow

that Heaven cannot heal.”6

The young soldier continued with other tunes, and at the close there was “a clapping of hands and the cheer from the Yankee lines.”7

It is comforting to know today, as it was a comfort then, that music could cheer and heal the broken-hearted, and stir those in need of inspiration.

In 1865, the day the news reached Washington of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Abraham Lincoln spoke to a crowd from his White House balcony. At the end of his remarks, he requested that a nearby band play Dixie, remarking that it was as fine a tune as he ever heard. His selection was another olive branch to the South, an invitation for them to return. And return they did.8

During the Civil War, music played a key role in a soldier’s life. The conflict inspired many poets and songwriters from both sides of the Mason Dixon Line.

When the war ended, these songs were put away for a time, as survivors longed to forget, along with their folded battle flags and war-torn uniforms. During the reunions that ensued, however, the songs were resurrected once again, bringing with them the memories of the days and comrades that were no more.

The songs brought back memories of camping in snow and heat, stacking arms by the fire, choking on dust-covered roads during long, weary marches, or burying their dead by moonlight. The memories evoked by these songs are now long quieted.

Most of the songs were partisan, favoring either the Union or the Confederacy. A few, though, appealed to both sides. The song All Quiet on the Potomac , for example, struck a chord with both the North and the South, as both sides camped along that great river that divided Virginia from the North. Other tunes, such as The Girl I Left Behind Me, Lorena, and Kathleen Mavourneen were haunting tunes of leaving behind their loved ones on both sides. Another favorite was Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground – which was sung as late as the Last Reunion at Gettysburg by the veterans, in 1938.

Soldiers often would “war” in song when the battlefield did not occupy them otherwise, and as the campgrounds were within a short distance from one another. Strains of Dixie were met by loud choruses of Glory Hallelujah across the picket lines in a contest to see which side could drown out the other.1

Dixie was undoubtedly the Confederate favorite. Ironically, it was written by Dan Emmett and Albert Pike and was sung in the antebellum years in New England and New York City music halls. At the outbreak of the conflict, Dixie was played at Jefferson Davis’s inauguration in Montgomery, Alabama. According to many soldiers’ accounts, General Pickett ordered the song played before his division embarked on their famous charge at Gettysburg.

Other Confederate favorites included The Bonnie Blue Flag, written by a Scottish actor, and When Johnnie Comes Marching Home, written by Louis Lambert.

The Union, too, enjoyed songs that were exclusively theirs. The favorite Glory Hallelujah or Battle Hymn of the Republic , originated as John Brown’s Body. It was changed early in the war, when in 1862, Julia Ward Howe heard marching soldiers singing the lyrics about John Brown’s body lying moldering in the grave, and she was horrified. She wrote much better lyrics, comparing the war to a crusade for righteousness. Soldiers sang both versions during the war. The song, at least the latter rendition, remains popular today.2

Along with the Battle Hymn , other favorite Union songs were Battle Cry of Freedom , written by patriotic Union composer George Root. Introduced in New York City at the start of the war in 1861, the song was instantly popular.

During the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, a brigade of Pennsylvania soldiers became separated from the rest of the Union troops and were surprised by a contingent of Confederates. Amid the daunting rebel yells, the men began to fall back in disorder. Suddenly, one of the soldiers began to sing Battle Cry of Freedom. The chorus caused the men to rally and they pushed back the Confederate force.3

The power of song was demonstrated many times during the war, inspiring the combatants from both sides of the conflict.

The soldiers’ good humor was sometimes made evident in song. Sometimes they compromised, or made-up versions of their own, such as this unique rendition of a well-known nursery rhyme:

Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow,

Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom!

And everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go,

Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom!4

When some of the troops from Buford’s Division entered Gettysburg, a group of girls from the town were so overjoyed to see them, that they gathered at the corner of Washington and High Streets and sang to them as the cavalry rode toward their positions. The music was a boon to the men, as they had been in the hostile South for so long. “Their countenances brightened,” remembered one, “and we received their thanks and cheers.”5

Music provided a needed solace to the wounded. On the night of July 2, 1863, a full moon hung over the Gettysburg battlefield where thousands were wounded, and many of them were dying. One Georgia soldier remembered that “one of our soldiers out between the lines, I think it was one of General McLaws’s men, began to sing. He was probably a boy raised in some religious home in the South, where the good old hymns were standard music…I have never heard music like that…in the still air and moonlight of that night, there were hundreds, perhaps thousands of desperately wounded men lying on the ground within easy hearing of the singer, whose fine voice rang out like a flute and echoed up and down the valley…There was a marked silence that could come only from attention. And I think the Federal line could hear him as well as ourselves. One of the hymns he sang was this familiar one:

“Come, ye disconsolate,

wherever ye languish,

Come to the mercy seat,

fervently kneel,

Hither bring your wounded hearts, here tell your anguish,

Earth hath no sorrow

that Heaven cannot heal.”6

The young soldier continued with other tunes, and at the close there was “a clapping of hands and the cheer from the Yankee lines.”7

It is comforting to know today, as it was a comfort then, that music could cheer and heal the broken-hearted, and stir those in need of inspiration.

In 1865, the day the news reached Washington of General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Abraham Lincoln spoke to a crowd from his White House balcony. At the end of his remarks, he requested that a nearby band play Dixie, remarking that it was as fine a tune as he ever heard. His selection was another olive branch to the South, an invitation for them to return. And return they did.8

Sources: Alleman, Tillie Pierce. At Gettysburg: Or What A Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle. New York: W. Lake Borland, 1889 (Reprint: Gettysburg: Shriver House Museum, 2015). Brainard, S. Our War Songs. New York: S. Brainard’s Sons, 1887. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster 2005. Hillyer, Captain George. My Gettysburg Battle Experiences. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2005. Osbeck, Kenneth W. 101 Hymn Stories. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1982.

End Notes:

1. Brainarad, p. 37.

2. Osbeck, p. 35.

3. Brainard, p. 45.

4. Ibid., p. 59.

5. Alleman, p. 29.

6. Hillyer, pp. 25-26.

7. Ibid.

8.Goodwin, p. 727.