Over the Rhine

by Diana Loski

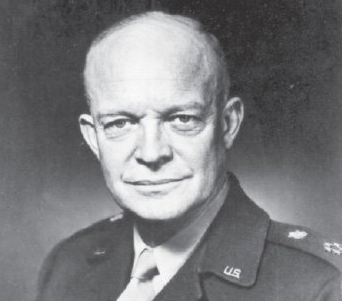

General Eisenhower, the man who beat Hitler

(Library of Congress)

Eighty years ago, the end of World War II appeared on the distant horizon over Germany. It was the time for which the innocent and honorable people of the world had long awaited.

Hitler and his Nazi ilk, however, bitterly contested every inch of their Fatherland. They realized that once the Allied troops traversed the Rhine River, the end was near.

In early March, General Eisenhower was eating dinner at his headquarters in Reims, a city in eastern France when the phone rang. It was General Omar Bradley with news. Ike remembered, “When he reported that we had a permanent bridge across the Rhine I could scarcely believe my ears...I fairly shouted into the telephone: ‘How much have you got in that vicinity that you can throw across the river?'" When General Bradley answered there were more than four divisions ready to cross, Ike was ecstatic and told him to go ahead. “That was one of my happy moments of the war.”1

The Rhine, according to Eisenhower was “a formidable military obstacle…It was not only wide, but treacherous, and even the level of the river and the speed of its currents were subject to variation because the enemy could open dams along the great river’s eastern tributaries.”2

The Nazis believed, as Hitler had told them, that the Rhine was their barrier to surrender. The Allies would never breach it. But, in early March, the Americans accomplished what the Germans had considered impossible. By March 22, many infantry divisions, artillery, and tanks were across the Rhine, including General Patton’s 5th Division of his Third Army.

The aforementioned bridge was the Ludendorf bridge at the town of Remagen. The Nazis had not yet destroyed the span, and the Allies quickly took advantage. One of the first soldiers over the bridge was platoon leader C. Windsor Miller, a lieutenant who lived in Pennsylvania during his retirement years. “I was always aware of the danger,” he recalled about the crossing of the bridge in an armored tank. It was a painstaking and precarious journey. Once the multitude of Americans reached beyond the banks of the river, the Germans were shocked to see them. “The river was supposed to be an insurmountable obstacle,” Miller said. “The present situation certainly reduced their morale to a new low.”3

Pontoon bridges were quickly added, and thousands more American troops reached the distant shore of the river, some near Remagen, others near Dusseldorf. The Americans overcame a stiff resistance at the town of Remagen, as they pushed through Germany, determined to reach Berlin. The Nazis continued to fight bitterly. It was, Miller remembered, “a journey that reeked of death every inch of the way.”4

Soviet forces, who had lost many millions in the war, were eager to wreak revenge on Hitler and his people. They pushed toward Berlin from the east, and Ike knew they would reach Berlin before the Americans and the British could get there. Ike carefully planned deployments, ensuring that the Allies coming from France and the Netherlands formed a barrier that kept any Nazi troops from the north, namely Scandinavia, or from the southern regions, like Austria, to join forces with those in Germany. He then penned a letter to the Germans: “I described the hopelessness of their situation,” Ike wrote, “and told them that further resistance would only add to their future miseries…But the hold of Hitler was still so strong and was so effectively applied…through the medium of the Gestapo and SS, that the nation continued to fight.”5

“When we got into Germany the Allied troops started finding forced labor camps,” recalled American soldier Edward Heffron. “People from Russia, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, most of eastern Europe, the Allied soldiers set them free, and put them in camps for displaced persons until they could get them situated.”6

General Eisenhower, too, visited one of the camps with General Patton, and the sights sickened them. He wrote about the ghastly conditions to George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, in Washington: “The evidence of bestiality and cruelty is so overpowering,” he wrote, “as to leave no doubt…about the normal practices of the Germans in these camps.” He told his superior in Washington that these camps were likely all over Germany, and urged the Allied troops to search for them to free those in similar conditions.7

The Allies also found many military prisoner of war camps, and freed thousands of American and English POWs. Ike remarked that “We had at one time 47,000 recovered American prisoners…Some of the Americans had been prisoners since the early battles in Tunisia in December 1942. On the British side we recovered men who had been captured at Dunkirk in 1940.”8

The Allies uncovered more than prisoners as they made their way toward Berlin. “General Patton’s army had overrun and discovered Nazi treasure,” Ike explained, “hidden away in the lower levels of a deep salt mine. A group of us descended the shaft, almost a half-mile under the surface of the earth…In one of the tunnels was an enormous number of paintings and other pieces of art…In another tunnel we saw a hoard of gold, tentatively estimated by our experts to be worth about $250,000,000, most of it in gold bars.”9

In the Pacific Theater, more Allied victories accrued. On March 26, the Island of Iwo Jima was secured by the U.S. Marines. A week earlier, the Americans invaded and captured Okinawa. While the war in the Pacific continued, the inroads made by the Americans were significant.10

Throughout the entire month of March, President Roosevelt looked old and tired. After meeting with Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in Yalta in February, he seemed unable to overcome his exhaustion from the trip. His wife and his aides insisted that he take a short vacation to rest. He left for Warm Springs, Georgia on March 29.11

On the morning of April 12, Roosevelt worked at his desk while an artist painted his portrait. He complained of “a terrific headache” and decided to lie down. A few hours later, he was discovered dead in his bed. The cause was a cerebral hemorrhage. He was just 63 years old, but like Lincoln before him, the war had taken its toll.12

At General Patton’s headquarters in Germany, Ike spent the evening planning the future, especially the ending stages of the war with Generals Bradley and Patton. “We went to bed just before twelve o’clock,” Ike recalled, “Bradley and I in a small house… and he [Patton] in his trailer. His watch had stopped, and he turned on the radio to get the time…While doing so he heard the news of President Roosevelt’s death.” Patton woke his two compatriots, with what Ike remembered as “shocking news.”13

There would be another shocking death before the end of April, which would hasten the end of the war in Europe.

On April 16, the Soviets reached Berlin and quickly encircled the city. One German historian wrote the result of that ordeal. “The Russians…charged vengefully…into Germany. Hitler forbade any evacuation plans, condemning the women…of Berlin to suffer the greatest phenomenon of mass rape in history, which led tens of thousands of victims to commit suicide.”14

The Americans reached Berlin on April 25. They had kept busy freeing thousands of prisoners, finding treasures, and keeping any reinforcements from reaching the rapidly diminishing German troops, as hundreds of thousands of the Wehrmacht were captured. By the end of April, the cities of Vienna and Bratislava also capitulated.15

On April 28, Benito Mussolini was executed, his body strung up in public for the Italian populace to witness. Two days later, on April 30, a desperate Adolf Hitler committed suicide in Berlin.16

The death of the Führer caused the collapse of German resistance. “Those Germans, they loved Hitler,” recalled Edward Heffron. “A German peasant said to me… ‘Why shouldn’t we be good to Hitler when he gave us all this?’ And he waved his hand to show me how beautiful the land was. And it was.”17

The land had been there long before Hitler, and, because the war was rapidly coming to a close, it would slowly recover from the terrible war he had instigated.

Nine days later, the end of the war in Europe was finally accomplished.

Eighty years ago, once the Allied troops crossed the Rhine River, the last barrier was breached, and the world’s most costly war was finally coming to an end.

Sources: Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1948. Guarnere, William “Wild Bill” and Edward “Babe” Heffron. Brothers in Battle, Best of Friends. New York: Berkley Caliber Publishing Group, 2007. Grun, Bernard. The Timetables of History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991 (reprint, first published in 1946). Hawes, James. The Shortest History of Germany. New York and London: The Experiment, LLC., 2017. Letter, Dwight D. Eisenhower to George C. Marshall, April 19, 1945. Copy, Dwight E. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, Kansas. Whitney, David C. and Robin Vaughn Whitney. The American Presidents. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1993 (reprint, first published in 1967).

End Notes:

1. Eisenhower, p. 379.

2. Ibid.

3. Miller, pp. 92, 101.

4. Ibid., p. 131.

5. Eisenhower, pp. 405-406.

6. Gurarnere and Heffron, p. 199.

7. Letter, DDE to GCM, Apr. 19, 1945, DDE Library, Abilene, KS.

8. Eisenhower, p. 420.

9. Ibid., p. 407.

10. Grun, p. 522.

11. Whitney, p. 277.

12. Ibid.

13. Eisenhower, p. 409.

14. Hawes, p. 187.

15. Grun, p. 522.

16. Ibid.

17. Guarnere and Heffron, p. 199.