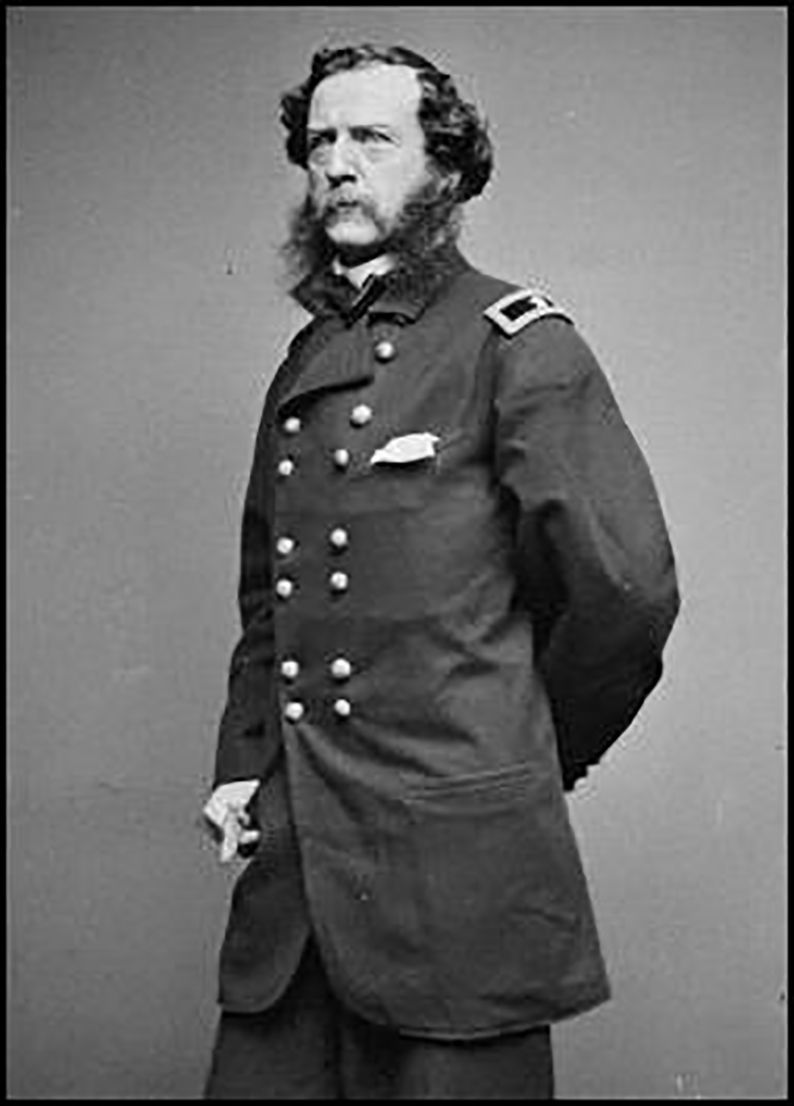

Samuel Wylie Crawford:

From Fort Sumter to Appomattox

by Diana Loski

General Samuel W. Crawford

(National Archives)

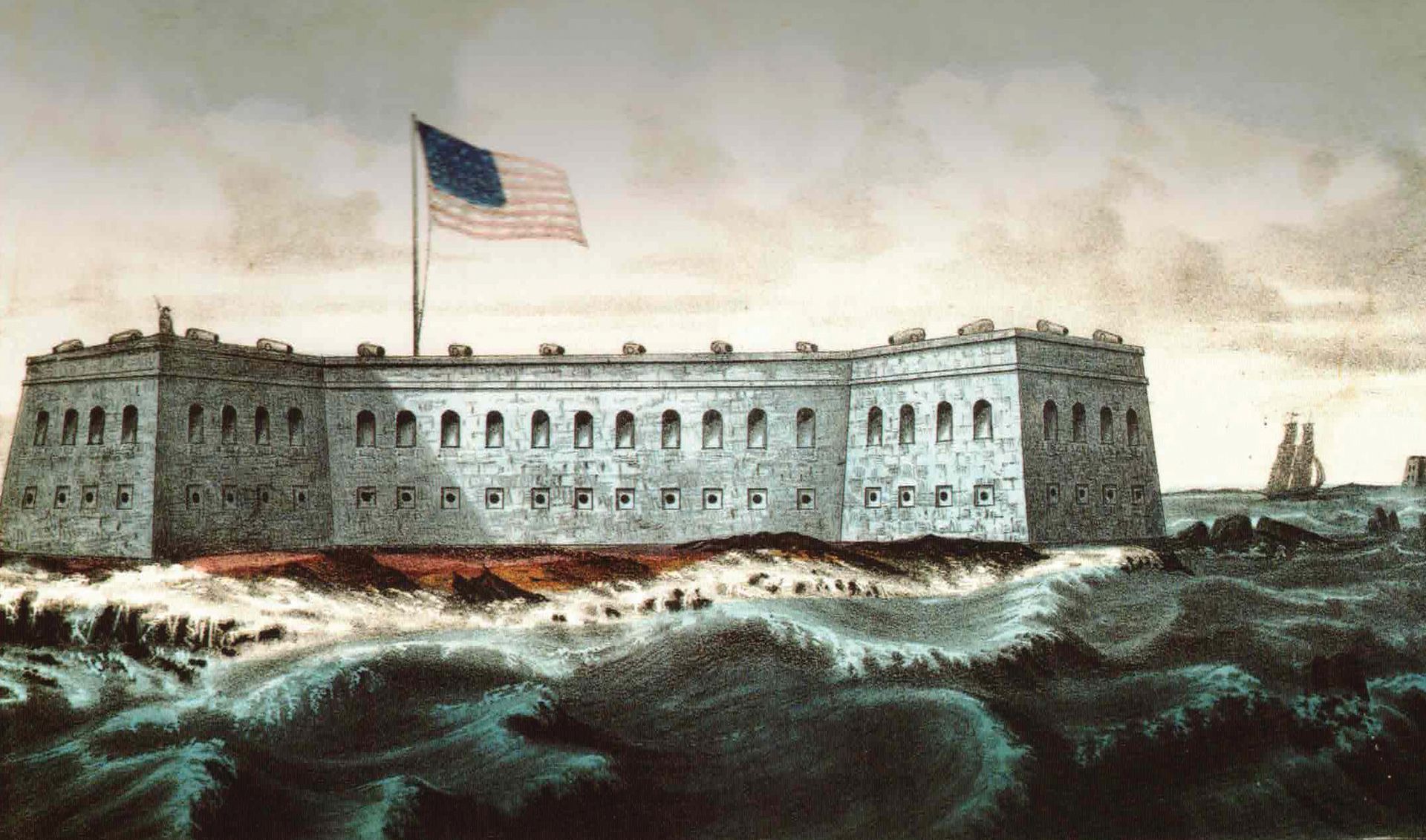

Samuel Wylie Crawford Jr. was born just a short distance from Gettysburg, in a mansion named Allendale, where the South Mountains rise to the west. His father was a minister and ardent abolitionist. His namesake son, who went by his middle name, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1846 at the age of sixteen, and as a post graduate he studied medicine. He became an assistant surgeon to the Federal Army, serving in various posts in the Southwestern territories and the state of Texas. In 1860, he was reassigned to Fort Moultrie at the Charleston Harbor. He served as the surgeon for Fort Sumter when the Confederates attacked on April 12, 1861.1

Though Crawford was a surgeon and not an official combatant, he asked the commander of the fort, Colonel Robert Anderson, if he could help with one of the batteries. Permission was given, which proved a turning point for the future general. In spite of the Union resistance, Sumter fell, and Samuel Wylie Crawford was incensed at the perceived perfidy. He traded in his scalpel for a sword, and never looked back.

Crawford accepted a commission as the commander of the 13th U.S. Infantry, and by the spring of 1862, he was named a brigadier general of volunteers. He first served in the Shenandoah Campaign against General Stonewall Jackson, and later fought in the battles at Winchester and Cedar Mountain. He was placed in charge of a brigade, made up of partly veteran and partly new recruits, in the Federal Twelfth Corps. It was with them that he fought at the Battle of Antietam, against General John Bell Hood’s Division in the woods that surrounded the famous Cornfield.2

Fort Sumter

Caption: An artist sketch of Fort Sumter, 1861

(Library of Congress)

Crawford spent the next several months back with his father in Pennsylvania to recuperate from his Antietam wound. When he returned to the army, he was given a promotion as the new division commander of the veteran Pennsylvania Reserves. The two brigades of Pennsylvania troops were battle hardened and resilient. They included men from Gettysburg in the ranks. They had been trained by two of the army’s great commanders: John Reynolds and George Meade. Crawford was given his command, which was part of the Federal Fifth Corps, while the army was marching toward Gettysburg. He caught up with them at Frederick.4

The Pennsylvania Reserves marched most of the night on June 30 to keep up with the quickly paced army. They reached McSherrystown on the night of July 1, and slept only a few hours before marching again, early on the morning of July 2, to reach Gettysburg, where the battle already had begun the day before. When they reached the environs of Powers Hill on the Baltimore Pike late in the afternoon, a member of Third Corps commander Dan Sickles’s staff led them, with General Slocum’s permission, to the rear of Little Round Top. By that time, the battle had begun again, and Crawford and his Pennsylvania Reserves rushed in to join the fight.5

The Third Corps, having been divided into three different places: Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard, were, sadly, placed with little thought to the dangerous places they occupied. With large gaps between the areas, Sickles’s men were mown down by the advancing Confederates. The Pennsylvania Reserves were as determined to stop them as much as was their commander. Crawford grabbed the colors as he rode, wresting them from the color bearer – who was unwilling to part with them – and led the troops forward. They formed a veritable “wall of iron”, refusing to give way, and stopped the Confederate forces – men from Generals Anderson’s and Benning’s troops – in their advance.6

Though the Reserves took casualties, they were veterans, and their determination held. One of the companies, known as Company K, part of the 1st Reserves, was comprised of men from Gettysburg. Crawford, too, considered the pastoral fields his home, and was determined to hold their position. Additionally, the Reserves had learned about the death of their former commander, John Reynolds, who had been killed on the first day. They were deeply saddened at the news, which gave them further impetus to stand firm. Once the fighting waned at sunset, Crawford made his headquarters near a wall and a large rock. His division remained through the night in the Valley of Death, just below and west of Little Round Top, near the edge of the Wheatfield. Crawford and his Reserves aided in keeping Confederate troops from scaling Little Round Top. The general was proud to have helped to save “ that rocky citadel ”, which proved a key location for the Union line. He also gave credit to the men who served under him. To Colonel Samuel McCartney Jackson, who commanded the 13th Reserves at the edge of the Wheatfield, Crawford exulted, “You have saved the day, your regiment is worth its weight in gold, its weight in gold, sir!”7

Crawford was recognized as “serving with great bravery and valor” at Gettysburg with his fearless division. He and his troops continued to fight with the Army of the Potomac through the rest of the war. Wounded again during the Overland Campaign, Crawford was recognized and brevetted for his courage in the battles of The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, the siege of Petersburg, and Five Forks. He achieved the rank of Major General by the end of the war.8

General Crawford was present at Appomattox, with his Reserves, when General Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865 – and the formal surrender ceremony two days later. It was just one day shy of four years, when he had fired upon the Confederate batteries from Fort Sumter. It is likely that General Crawford is the only military officer who was present at Fort Sumter, Gettysburg, and Appomattox Court House.9

After the war, Crawford remained with the Federal army, and aided with reconstruction. Knowing that Gettysburg needed preservation, he purchased the land below Little Round Top, where he and his division had fought, and donated it to battlefield preservation. For a time, he also served on the preservation board, and for a few years as its director. He retired from Federal service in 1873, citing the wounds he had received during the war, the one from Antietam still causing him trouble. He wrote prodigiously, including a memoir that was published posthumously, of his experiences during the war. He also carefully preserved his uniform and his medical implements.10

A wealthy bachelor, General Crawford often wintered at a Philadelphia hotel. It was there on November 3, 1892 that he died from the effects of a stroke, at 63 years old. He was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery, not far from his old commander at Gettysburg, George Meade – who had died twenty years earlier.11

In 1913, funds were raised to erect a portrait statue of the Pennsylvania general in the Valley of Death. Governor John Tener, however, put a moratorium on proceeding with the memorial, in part due to the coming 50th Reunion of the Blue and the Gray at Gettysburg. Years passed, but the memory of Crawford and his Reserves remained – and the widespread initiative for a statue revived. The memorial, which stands near the spot where General Crawford grasped the colors on July 2, 1863, was sculpted by artist Ron Tunison, and dedicated in 1988. That same year, the general’s frock coat and medical chest were donated to Gettysburg National Military Park.12

Today, Gettysburg National Military Park looks much as it did on the late afternoon of July 2, 1863. Part of the reason it has been preserved for all generations is due to the work of Samuel Wylie Crawford, one of many who stood resolutely to defend his country, and then worked to preserve it – from Fort Sumter to Appomattox – and especially at Gettysburg.

Crawford statue

Caption: The Crawford Portrait Statue, Valley of Death(Author photo)

Sources: Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Drake, Francis Samuel, Ed. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography . Vol. V, New York: 1889. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam . New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1983. The Gettysburg Compiler, 08 November 1892. The Gettysburg Times, 26 May 1987. The Gettysburg Times, 10 March 1988. Ohiocivilwarcentral.com/Crawford . Nps.gov/gett/Crawford . The Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 November, 1892. The Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 November, 1892. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge & London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964 (reprint 1992). Additional information found on the Crawford portrait statue, Gettysburg. All historic newspapers accessed by newspapers.com .

End Notes:

1. Gettysburg Times, 26 May 1987. Drake, p. 22. Warner, p. 99.

2. Ibid.

3. Sears, p. 206. Warner, p. 309. Ohiocivilwarcentral.com/Crawford .

4. Pfanz p. 49. Coddington, p. 334. The V Corps, as Crawford made his way to Gettysburg, was still com-manded by George Meade. He was promoted to army command three days before Gettysburg, and was replaced by General George Sykes as V Corps Commander.

5. Coddington, p. 345. Pfanz, p. 391. The Gettysburg Compiler, 08 Nov., 1892.

6. The Gettysburg Compiler, 08 Nov., 1892. Pfanz, p. 49. Crawford Memorial Gettysburg. The color bearer was Corporal Bertless Shot, who remained near the flag while Crawford carried it.

7. The Philadelphia Inquirer, 04 Nov., 1892. Pfanz, pp. 393, 401.

8. Warner, p. 99.

9. Ohiocivilwarcentral.com/Crawford . Two other generals who fought at Gettysburg were also at Fort Sumter: Abner Doubleday and Norman Hall. Neither were present at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

10. The Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 Nov., 1892. The Gettysburg Times, 10 Mar., 1988.

11. The Philadelphia Inquirer, 04 No., 1892.

12. Nps.gov/gett/Crawford. The Gettysburg Times, 10 May, 1988.