When the war came, volunteers flocked from hamlets, towns and cities all over the broken nation to enlist, from both the North and the South. They were grouped into units called regiments, commanded by a colonel. These regiments had been built from groups of one hundred – usually from sections of cities, or provided by the populations of towns and the smaller villages. These smaller units were known as companies, and they were led by a captain. Regiments were numbered, like the 87th Pennsylvania, while companies received their titles based on letters, starting from A and following down through the alphabet.

With ten companies of one hundred filling most regiments of one thousand at the beginning of the war, their letters usually stopped with J. Pennsylvania, though, superseded its quota. Men from Gettysburg and the surrounding towns formed, then, a Company K.

The boys from Company K, the First Pennsylvania Reserves, part of the Army of the Potomac, were born and raised in and around Gettysburg.

Over 158 years ago, this company of men from Adams County waited for their orders on July 2, 1863 among the boulders and woods behind the Round Tops, where they had once played hide-and-seek and hunted rabbits during the halcyon days of youth. Barely into their manhood, they were prepared to fight wherever they were needed. They were about to fight, literally, for their homes.

When the order to attack rang through smoke-filled chaos, these boys in blue yelled, “Revenge for Reynolds!” and swept fearlessly into the Valley of Death and the Wheatfield beyond it.1

With most of the battles up to that time fought in the South, the Confederate soldiers had the advantage, and precious privilege, to fight on their own soil. It was an advantage that Union artillery commander General Henry Hunt, on quoting Napoleon, remembered: “the same army is a different thing under different circumstances…the moral is to the physical as three to one.”2

If there were ever a moral advantage for the Union soldiers from Pennsylvania, the Battle of Gettysburg provided it for these boys who called the battlefield home.

Company K was organized in 1861 as part of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps. When Pennsylvania men flocked to enlist, they gave an overabundance of volunteers. The Federal government, thinking the war would end soon, did not accept them, feeling there was no need of them. The state of Pennsylvania then accepted them, trained them, and prepared them for war.

Enlistment in Gettysburg was impressive. Farmers, carpenters, brick layers and laborers joined with teachers, lawyers, with an engineer and a member of Congress to be part of the Pennsylvania Reserves. These honorable men from different facets of life forged their common bond to defend the Union. One Gettysburg man was 23-year-old Henry N. Minnigh. One of twelve siblings, he had left a teaching position in the summer of 1861 to enlist. He remembered they were all “volunteers, none forced into service, no bummers, no bounty jumpers.”3

The majority of these men came from Gettysburg, but others joined from other hamlets and towns of Adams County, including York Springs, Fairfield, and East Berlin. Over half were under 21 years of age. Their commander as Captain Edward McPherson. Company K became attached to the 30th Regiment under Colonel Roberts, though they preferred to call their regiment by its other name, the First Pennsylvania Reserves. Their brigade commander was another courageous Pennsylvanian and West Point graduate, John F. Reynolds from nearby Lancaster.

Barely a month after mustering the company, Captain McPherson resigned his command to return to Congress. Captain J. Findley Bailey took over the command of Company K. The boys drilled and trained, eager to get into the fight. It came months later, with the Peninsular Campaign in the late spring and early summer of 1862.

The campaign was the result of an attempt by army commander General George B. McClellan to take Richmond – the capital of the newly formed Confederacy. A series of bloody conflicts in late June, known as the Seven Days Battles, proved that the Southerners held a tenacious grip on their homeland. Many boys in blue were slain in the attempt, including Company K’s Captain Bailey. Equally distressing was the capture of their brigade commander, John Reynolds.

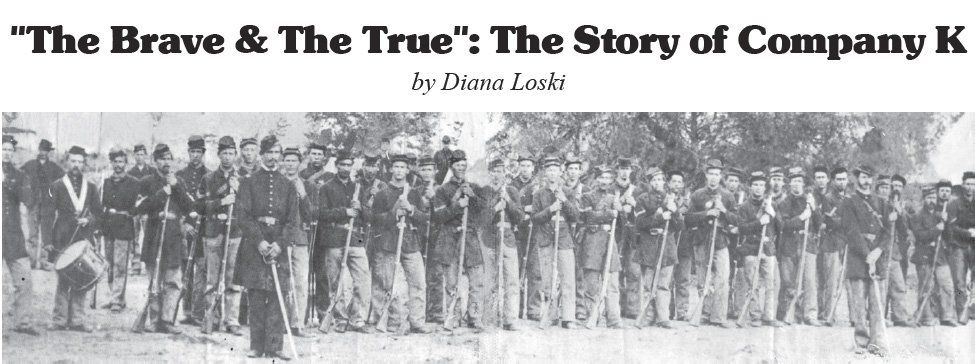

Company K fought at the Battle of South Mountain, where they sustained a number of casualties. Sergeant Henry Minnigh was one of them, with a bullet in the arm. Fortunately, he survived. Because of the large number of wounded, only about a dozen of the boys from Company K fought at Antietam and they did not participate in the ensuing fight at Fredericksburg. In early 1863, Company K was dispatched for the defenses of Washington, D.C. They remained in that position through early June, where they posed for a photograph. Their new commander was Captain Henry Minnigh.

When the alarming news spread that General Lee was on the move northward, Company K joined the First Reserves once more. With the reorganization of the army, the Reserves by this time formed part of the Federal Fifth Corps under General George Sykes, with General Samuel Wylie Crawford, a self-made millionaire from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, as their division commander. Their brigade commander was Colonel William McCandless, A Pennsylvania man who had joined the Second Reserves as a private and through personal bravery rose through the ranks. Their regimental commander was now Colonel William Cooper Talley, a native of Philadelphia, and fellow former member of the Second Reserves.4

Crawford’s Division, with Company K in tow, reached Gettysburg early in the morning of July 2, after marching on the Hanover Pike. When they reached the outskirts of home, the boys saw familiar faces and sites. Some called to the people they recognized by name, but the locals did not recognize the young men who had left home two years earlier. They had changed since they left town, and, apparently, significantly. After the exhausted men reached Rock Creek behind the Round Tops, they learned the dreadful news that their former brigade commander, General John Reynolds, had been killed on Gettysburg’s first day. The beloved general would never touch the handsome sword the men had purchased for him.5

Unknown to the valiant Reserves, during the afternoon the Federal commander of the Union Third Corps disobeyed orders and moved his sizable troops from the main Union line out to the Emmitsburg Road, deploying in places like Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, and the Wheatfield, leaving the Round Tops unprotected. Soon the Confederates attacked the Union soldiers in those places, and the Pennsylvania Reserves were summoned.

“About four o’clock we were hurriedly called into line,” remembered Captain Minnigh, “and ordered to sling knapsacks, which command to us always meant ‘get ready for quick and devilish work’.” Marching at the double quick, they arrived at the base of the Round Tops and saw “the field of carnage” and could hear “the victorious shouts of the enemy…the general outlook being anything but assuring.”6

As the vanquished Federals from the Third Corps hastily retreated, the Reserves waited until their way was cleared. At the order, they fired two volleys of musketry into the advancing gray line, then with a cheer, they ran into the field of fire. Crossing the Valley of Death and the creek known as Plum Run – made crimson by the blood of the surrounding wounded and dying – they hastened to hold their position at the edge of the Wheatfield. The wheat, already crushed by the battle that had taken place, was filled with Confederates, ready to meet the Reserves in a head-on collision.

The Pennsylvania Reserves, with Company K of the First Reserves in tow, stood resolute and unmovable. They continued forward, with their young color sergeant boldly displaying the regimental colors. The regiment dutifully followed him. When Colonel Talley shouted for the color bearer to return to the regiment, he was certain the young man could not hear him from the deafening roar of the fight.

He did hear it, but refused to retreat. “No sir!” he called. “Let the regiment come to the colors!” There was no going back, only forward. The men from Company K and the remainder of the First Reserves readily complied.7

The Confederates, exhausted from their fight with the Third Corps, ceased to press the Union troops, and the Reserves halted on the edge of the Wheatfield. The Union left had held, and though the Confederates claimed the Wheatfield, the Reserves remained in place until the Southerners retreated the next day. One member of Company K, a young shoemaker named William McGrew, was mortally wounded in the fight and three others were wounded.8

The Reserves remained at their position for the night and the following day they watched the repulse of Pickett’s Charge. As the news of Union victory traveled down the line of deployment, the boys from Company K wanted to visit their homes, anxious for the safety of their families. Leave was denied by the superior officers, but Captain Minnigh, who wanted to see his family too, told the men to be back for roll call the next day.

Minnigh hurried in the early evening for his family home on the corner of Washington and Middle Streets. There, he found his family in the cellar, where they had hidden for three days. They were distraught and fearful and unaware of what had transpired. When they noticed in the coming darkness a Union soldier at the top of the stairs they did not know who he was. Always one to appreciate a little humor, Minnigh merely asked for something to eat. His sister, Lucy, glumly repeated his request to their mother, who obligingly opened their pantry. She approached the dust-covered soldier, peered into his face, and smiled, recognizing her son at last. “Oh, you bad fellow,” she said. “I know you now!” She handed him a piece of bread and added, “Here’s your supper.”9

The Minnigh home, like many others in Gettysburg, brightened during the July 3 twilight at the arrival of its unexpected guest. Minnigh wrote that they were “brought…from that lower world, in which they had dwelt for several days, into the light and comfort of the upper world once more.”10

The men from Company K returned to their ranks on July 4, and soon followed the escaping Confederates back into Virginia. They participated in the Overland Campaign of 1864, which comprised the battles of The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, and Bethesda Church – the precursor of the terrible battle at Cold Harbor. By mid-June 1864, their three-year enlistment had expired. Some reenlisted in the 190th Pennsylvania Infantry, but others, like Minnigh, went home.

The Adams County heroes arrived in Gettysburg on June 13, 1864, after having been mustered out in Philadelphia. A citizens’ banquet was held that night in their honor, but few of the men attended. They just wanted to go home – the place that mattered most to them.

Captain Minnigh recorded, “Of the 110 who had gone forth three years before, only 24 returned….We cherish the memory of our fallen comrades, and as one by one we are summoned to join the great majority, we hope to meet them again, and to stand side by side, in nobler array, with the brave and the true.”11

Over one hundred and fifty years later, the men from Company K have all been summoned. Some, like Captain Minnigh and William McGrew, lie in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Others rest in family plots in Adams County. Some are buried in unmarked graves in the South.

In 1991 a monument was placed in Lincoln Square to memorialize the boys from home who fought at The Battle of Gettysburg. Over 2,000 Pennsylvania Reserves answered the call, and many of them – like those from other states north and south, did not return.

Company K will always be famous in Adams County, Pennsylvania. They will always be “the only home company that saw service in the battle here.”12

In today’s uncertain times, we can take solace in remembering those forebears who dutifully left the comfort of their homes, families, and personal liberty to fight for those cherished people, places, and for freedom for all. They faced their formidable foe in the summer of 1863 – in the fields and hills they always called home. They did not falter, but held their ground, resolutely going forward. They remain the greatest example, like those who fought with them at Gettysburg, 158 years later.

The Company K Memorial, Gettysburg

(author photo)

Sources: Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. The Harrisburg Daily Independent, 27 November, 1915. Minnigh, H.N. History of Company K: The Boys Who Fought at Home . Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 1998 (Reprint). Henry N. Minnigh Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Singel, Lt. Gov. Mark. “Dedication Speech, Co. K Monument, June 29, 1994. Copy, Gettysburg National Military Park. Colonel William Talley Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

End Notes:

1. Singel, June 29, 1994.

2. Coddington, p. 46.

3. Pfanz, p. 49. Minnigh, p. 33. Henry Minnigh Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

4. Coddington, p. 577. Pfanz, p. 547. Talley Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

5. Minnigh, pp. 48-49. Coddington, pp. 334-335.

6. Minnigh, p. 50.

7. Singel, June 29, 1994.

8. Minnigh, p. 143.

9. Ibid., p. 144-145.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid., p. 67.

12. Harrisburg Daily Independent, 27 Nov., 1915.

Editor’s Note: In the photo of Company K, taken in Washington shortly before the Battle of Gettysburg, Captain Henry Minnigh is pictured to the left and front of the company.