The Historic Retreat

by Diana Loski

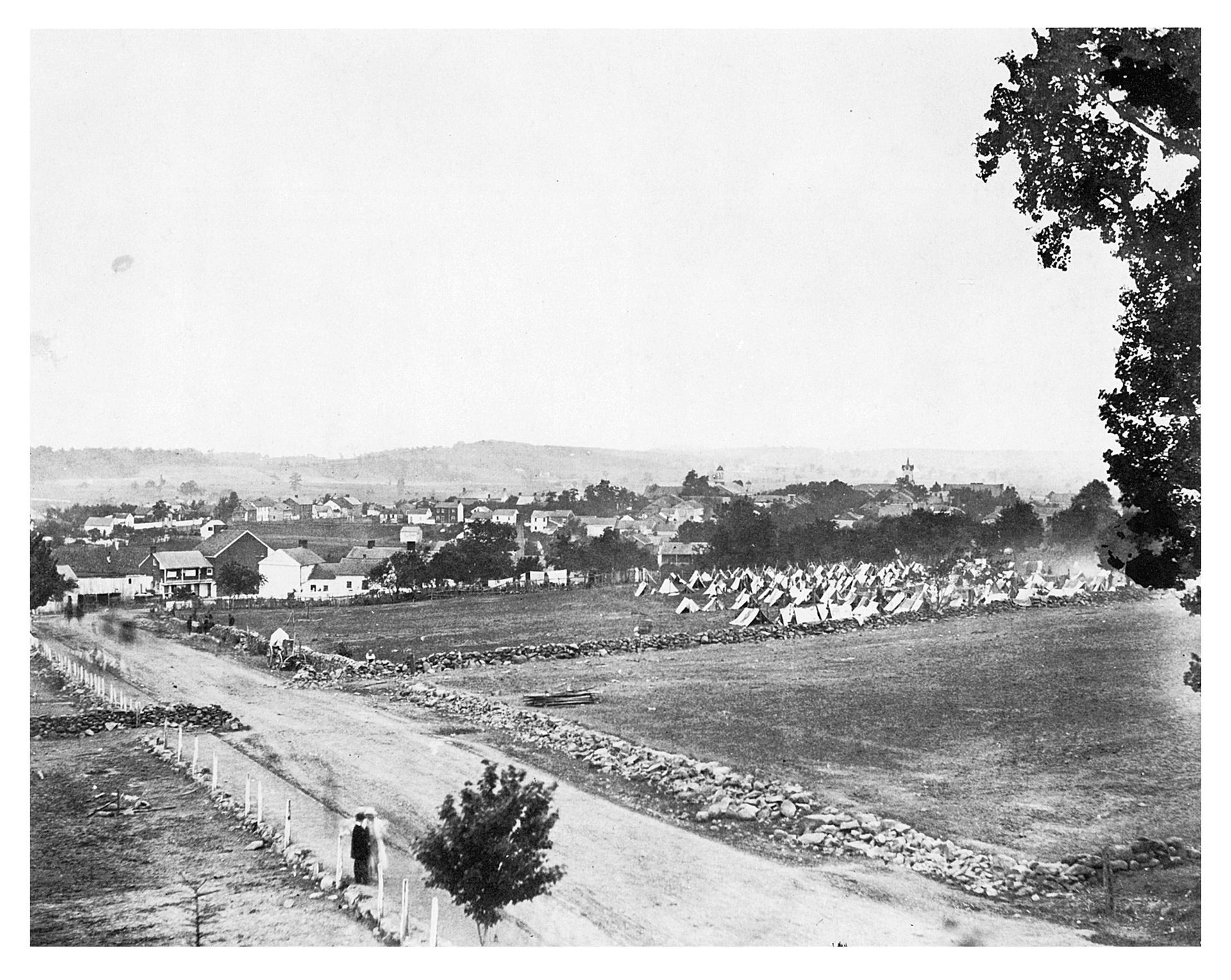

Gettysburg 1863 (Library of Congress)

The Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the Civil War, involved approximately 170,000 men “masses of humanity, surging and resurging the one against the other”. When the guns grew silent, both armies needed to vacate the farmers’ fields and leave thousands of wounded in the town and its surrounding farms.1

Because Gettysburg was a Union place, and because Lee and his army did not prevail there, General Lee knew that if General Meade did not counterattack him on Seminary Ridge – and soon – that he would have to retreat. As July 4 dawned and no attack came, Lee made plans to retreat, while simultaneously preparing for a possible attack from the Union forces.

On the Federal side, General Meade knew that, in order to claim victory, that his army would have to stay and allow Lee to withdraw first. The result put Meade, a Pennsylvania man, in a quandary. The quickest route to the Potomac River – and Lee’s safety – was through Fairfield and Hagerstown, towns divided by mountains and their narrow passages. Once Lee reached the heights, it would be impossible for the Union to gain an advantage over the men in gray.

General Meade has been vehemently criticized, from 1863 to the present day, for allowing Lee and his battered army to escape – resulting in another nearly two years of war.

The judgment against George Meade, though, in hindsight, appears unjust. Lee’s army was far from demoralized. While the Battle of Gettysburg was horrendous and the Confederate defeat there was excessively costly to both sides, Gettysburg was the first battle where the Army of Northern Virginia definitely lost while Lee led them, and they were not ready to give up yet. Both sides had to recover from their losses, and their surviving troops were exhausted and needed rest before they could continue to fight. Both sides lost commanders and some of their choicest men.

While General Lee admitted to losing 20, 451 men at Gettysburg, it is definite that he lost far more. The Confederate wounded and captured alone totaled nearly that number, and the dead were “thick as fallen leaves in autumn” on the field – the majority of them Confederate slain left to decompose – which they did for many weeks. An Ohio journalist who visited the battlefield in late July remarked that “the whole field was horribly oppressive…clots of blood, pieces of limbs of the poor men, and other horrible sights met the eye at every turn. Some of the rebel dead yet lie unburied.” In addition to those left at Gettysburg, Lee’s extensive wagon train of wounded stretched for 17 miles. The wagons included some of the Confederate high command, like Generals Dorsey Pender and John Bell Hood, who were too severely wounded to move but too valuable to be left behind.2

George Meade lost three corps commanders, and two of them – John Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock – were irreplaceable. Like General Stonewall Jackson had been to Lee, Reynolds and Hancock were exceptional leaders, and their loss was unfathomable to the Army of the Potomac. While Hancock did survive the war, his Gettysburg wound was so acute that he was unable to lead in the field (although he briefly attempted it), and ended up behind a desk in the final months of the war. Meade also lost his Chief of Staff, Dan Butterfield, who had been wounded in the battle. He replaced him with the capable A.A. Humphreys.3

Meade knew, additionally, that once Lee attained high ground that he would aggressively hold it; moreover, Lee expected Meade to attack him on the retreat from Gettysburg and was ready for him. Meade wisely sought, instead, to send cavalry to “harass and annoy” Lee’s retreating troops and follow Lee by the flank, hoping for a chance to do battle before Lee escaped into Virginia.4

Lee and his army left Gettysburg on the evening of July 4, 1863 – the same day that Vicksburg, Mississippi surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant, giving the Federals control of the Mississippi River. It was a significant concession.

In southern Pennsylvania and Maryland, skies poured rain, flooding the fields and turning creeks into raging currents. The roads became a morass of mud, making travel difficult and nearly impossible. One who traveled with the Southern army remarked that “the road was a sea of slush and mud, and we got along very slowly.”5

The troops on both sides were completely worn out. “It was certainly a dismal night,” remarked one soldier on Seminary Ridge the night of July 3. “Lee and Longstreet stood apart engaged in earnest conversation, and around the fire in various groups lay the officers of their staffs. Tired to death, many were sleeping in spite of the mud and drenching rain.”6

Their Union counterparts were equally fatigued, and needed rest and nourishment. Since Union supplies were nearby in Westminster, Maryland, Meade ordered the wagons forward to feed his men. Due to typical government slowness, the trains did not arrive in a timely manner. Additionally, Meade received new recruits to replace his losses at Gettysburg. These troops, who were numerous, were nevertheless untried in battle – and Meade was not eager to press them against Lee’s men, entrenched in the mountains, for their first fight. Finally, on July 7, the bulk of the army left Gettysburg, with a few left behind to tend to the wounded.

General Sedgwick, who commanded the Federal Sixth Corps, had gone ahead to scout out the enemy position. He saw the Confederate entrenchments in the hills and mountainous terrain beyond Fairfield and alerted Meade. In addition, more torrential rains plagued the pursuing Union soldiers on July 7 and 8, while Lee pushed on toward the Potomac.7

General William H. French, who was in control of the District of Harpers Ferry during the Battle of Gettysburg, was informed of Lee’s hasty retreat and dispatched troops to Williamsport, Maryland where they destroyed Lee’s only pontoon bridge across the Potomac. The troops also captured a supply of ammunition and dumped it in the river. The loss of the bridge, with the already swollen waters that made any crossing impossible on foot or horseback, hampered Lee’s escape.8

General Meade wisely sent his troops through Maryland as the macadam roads made marching easier. The Union troops traveled swiftly, some as much as thirty miles in a day. Within days, the majority of Meade’s infantry had reached Lee’s position. On July 11, as the Potomac continued its swollen state, Union forces drew close, notably the Sixth and Eleventh Corps. Meade arrived, and noting Lee’s strong and entrenched position, ascertained that “Its flanks were secure and it could not be turned.”9

Cavalry troops continued to harass the Confederate position, but the main body of Meade’s men did not attack, as Meade thought the plan unwise.

The political leaders in Washington, unaware of the situation, and hearing otherwise, demanded that Meade attack the Confederates. Meade was, however, as history has proven, correct. General Humphreys wrote, “An assault upon it would have resulted disastrously for us.” He added, “General Meade was…greatly blamed for not attacking, and he was also criticized for not following Lee more rapidly. On the other hand, General Burnside was severely criticized for attacking at Marye’s Heights…where the entrenchments were not more formidable than those of Williamsport.”10

The Confederates concurred. An officer in the gray stronghold was heard to say, “If he attacks us here, we will pay him back for Gettysburg.”11

On Sunday, July 12 the Potomac River fell five feet, making it possible to ford at last, at least on horseback and for those men who were taller. Confederates pulled down houses and sheds, taking the planks to make pontoons. Two days later, on July 14, the bulk of the men in gray began to cross the river. It was a terse and frustrating time for both armies, as Union cavalry continued harassment and skirmishes continued.

In the fray, another Confederate general was mortally wounded. General J.J. Pettigrew, who had taken part in Pickett’s Charge, chased a Union cavalryman acting as a sniper, with his pistol. The dismounted horse soldier, however, managed to shoot Pettigrew instead. He was the last general officer killed in the Gettysburg Campaign.12

A Confederate described the scene that last day of the campaign, with “rain falling in torrents, the road being obstructed by wagons and artillery trains which seemed almost to creep. This of course rendered our position critical.”13

Lee and his army, then, crossed the river into Virginia. The Gettysburg Campaign ended, and the war was destined to continue on that side of the river. Meade, unable to destroy Lee’s army – which was an impossible task at that time – had at least succeeded in avoiding Lee’s trap along the banks of the Potomac, and spared his men to fight another time.

The newspapers criticized the Union commander and for a time Meade was in danger of losing his command. Meade’s generals, however, approved of the job he had done. After all, the Union forces won at Gettysburg, and Lee’s men would never be the fighting force they had been before those first three days in July in 1863.

General Slocum, who commanded the Twelfth Corps at Gettysburg was one who defended General Meade. He wrote to a friend, “Please don’t believe the newspapers when they tell you that we could have captured…the rebel army – our best officers think everything was done for the best.”14

It would be many months before Lee and Meade met again. Their next battle took place at The Wilderness in May, 1864. Before that time, both sides would accept recruits and train them to fight their formidable foes. And there would be an additional commander: Ulysses S. Grant, fresh from his victory at Vicksburg. Gettysburg was officially relegated to history – and what a history it was.

Sources: The Boston Morning Journal, 7 July 1863 (Newspaper Accounts File, Gettysburg Campaign, Gettysburg National Military Park – hereafter GNMP). Baumgartner, Richard A. Buckeye Blood: Ohio at Gettysburg. Huntington, WVA: Blue Acorn Press, 2003. Cleaves, Freeman. Meade of Gettysburg. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Humphreys, A.A. From Gettysburg to the Rapidan. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1883 (copy GNMP Library). Pool, S.D., ed. “Our Living and Our Dead.” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol I, Sept. 1874-Feb. 1875. Copy, GNMP. Ross, Fitzgerald. “A Visit to the Cities and Camps of the Confederate States.” Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1865 (Retreat of the Army of Northern Virginia File, GNMP). The St. Louis Democrat, 6 July, 1863 (Newspaper Accounts File, GNMP). Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.

End Notes:

1. The St. Louis Democrat, 6 July, 1863.

2. Coddington, p. 536. Boston Morning Journal, 7 July, 1863. Baumgartner, p. 184.Hood survived the homeward ordeal, but Dorsey Pender, whose wound continued to bleed during the trip, died shortly after reaching Virginia.

3. Cleaves, p. 173. Humphreys was formerly a division commander in the Federal Third Corps.

4. Coddington, p. 543.

5. Ross, p. 73. Fitzgerald Ross was an Austrian military man and diplomat traveling with the Southern army.

6. Ibid.

7. Humphreys, p. 3.

8. Warner, p. 162. Coddington, p. 542. Cleaves, p. 174.

9. Humphreys, pp. 6-7.

10. Ibid.

11. Cleaves, p. 182.

12. Pool, p. 31.

13. Ibid.

14.Coddington, p. 574.