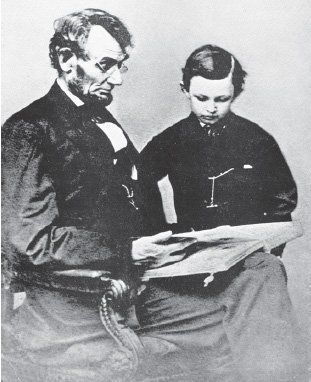

Lincoln and son Tad

(Library of Congress)

In addition to the millions of American citizens who suffered through the war, there is one man who suffered, along with his family, as much or more than anyone. Abraham Lincoln, even today, is considered either the greatest American president or the most hideous of tyrants. One fact is inarguable: he and his entire family paid a most terrible price for his tenure during the war.

“From early youth [Lincoln] seemed conscious of a high mission,” Lincoln bodyguard and friend Ward Hill Lamon wrote, and “from a lofty station he should fall.” Lamon also remembered that Lincoln was resigned to the fact that “he had felt for many years he would suffer a violent death.”1

Even before he rose to the office of the Presidency, Abraham and Mary Lincoln were not strangers to great sorrow. Both lost their mothers while they were still children, and both lost siblings with whom they had shared close ties. These losses caused them to exhibit a combined indulgent nature toward their own four sons: Robert, Edward, William and Thomas – which gives evidence of a lacking from their own unhappy childhoods. Their second son, Edward, died as a toddler of a childhood disease, possibly tuberculosis. He was often ill while his father rode the circuit – a necessity for most lawyers in the new state of Illinois – while Lincoln supported his family. In one letter to her husband while he was thus engaged, Mary Lincoln wrote, “ Eddy’s eyes brighten at the mention of your name.” Eddie’s death in 1850, at barely four years of age, devastated his parents, but soon after his passing, Mary discovered that she was expecting another child. Their third son, William Wallace Lincoln, was born in December; he was considered a great favorite with his parents, and exuded a promising future.2

“Dear Willie, he was pure gold,” remembered Julia Taft, who often spent time in the Lincoln White House with her younger brothers, Bud and Holly, who were the Lincoln boys’ playmates. She added that Willie “was the most lovable boy I ever knew, bright, sensible, sweet tempered and gentle mannered. Tad had a quick, fiery temper, very affectionate when he chose but implacable in his dislikes.” It appears that Willie had the Lincoln manner and the Todd appearance; Tad, who hated being called by his Christian name, Thomas, had instead the Lincoln looks and the Todd disposition. He exhibited learning disabilities and had a speech impediment. 3

Lincoln’s law partner, William Herndon, recalled that while he shared a law office with the future President, that on Sundays Lincoln brought Willie and Tad to the office while Mary attended church: “ The boys were absolutely unrestrained in their amusement. If they pulled down all the books from the shelves, bent the points of all the pens, overturned inkstands, scattered law papers over the floor or threw the pencils into the spittoon, it never disturbed the serenity of their father’s good nature. Frequently absorbed in thought, he never observed their mischievous but destructive pranks – as his unfortunate partner did.”4

The Lincoln Home, Springfield, Illinois

(Author photo)

Mary Lincoln, born to a wealthy Lexington family, had been cast aside by her stepmother and largely ignored by her father after she lost her mother at age six. Many historians and contemporaries offer the explanation that Mary suffered from mental illness as well, including depression and possibly narcissism. Whatever her deficiencies, she recognized greatness in Abraham Lincoln, loved him deeply, and aided him in his efforts toward high political status. While some claim that Lincoln merely bore the tedious marriage, to the contrary, he did love her. At a White House function, he remarked to a guest, “my wife is as handsome as when she was a girl and I a poor nobody then, fell in love with her and once more, have never fallen out.”5

The White House years, in the midst of the turmoil of war, were difficult ones for the Lincolns, and because of the great demands made upon the President, his wife spent much time without him. “I consider myself fortunate,” she once said, “if at eleven o’clock I once more find myself in my pleasant room and very especially if my tired and weary husband is there, waiting…to receive me.”6

With death threats, a dissolved nation, numerous journalistic attacks on both Lincolns, the four years in Washington were unhappy ones for them. When Mary refurbished a run-down executive mansion, she was excessively criticized. Whatever action the President took to protect the Union, he was maligned. Their sons, too, were not immune. Robert was away at Harvard, but Willie and Tad were sometimes pulled into controversy. One day Tad asked Julia Taft for the definition of a mudsill. “Why, a Yankee, Tad,” she answered. “Well,” Tad went on, “ a boy in Lafayette Square said we were ‘em and we am not.”7

Willie then offered, “Of course not…Everybody knows they come from Connecticut.” Tad wanted to “punch ”the offender, but Willie discouraged him, saying it would make the papers.8

The close friendship between the Lincoln boys and the Taft sons ended abruptly with the death of Willie Lincoln on February 20, 1862. The cause was “a bilious fever” which was almost certainly typhoid fever, which spread unrelentingly throughout Washington due to the influx of soldiers and the contaminated water supply. Had the Lincolns remained in Illinois, the son of great promise would likely have lived to adulthood. Mary Lincoln was inconsolable and immediately banished the Taft boys from the White House – their presence caused her too much grief. She sent away all of Willie's belongings to family in Springfield, erasing all reminders of his existence. She also neglected Tad, as he too reminded her of her lost son. Abraham Lincoln, too, was deeply grieved – every Thursday (the day of Willie’s passing) he shut himself in his son’s room and sat alone – sometimes for hours. Mary spent yeas seeking out clairvoyants. At least eight seances took place in the White House between 1862 and 1863.9

Tad, the lone son left in Washington, also suffered from the loneliness. He experienced recurring nightmares, and often ended up in his father’s room – as the Lincolns had adjoining bedchambers.10

Like so many families during the war years, the Lincolns experienced painful separations from extended family, mainly from the Todds. Most of Mary’s Kentucky-born siblings sided with the Confederacy. Mary lost three brothers and one brother-in-law in the war. General Benjamin Hardin Helm, killed at Chickamauga, was the husband of Mary’s young half-sister, Emilie, Mary’s favorite sister. In December 1863, the Lincolns invited her for a visit, which created a major controversy. General Dan Sickles, who recently lost a limb at Gettysburg, expressed outrage that the unrepentant rebel woman was in the White House. Emilie gave him a vindictive reply: “ If I had twenty sons, they would all be fighting yours.” When Emilie demanded special favors of her brother-in-law, without taking an oath to the Union, Lincoln refused to give them to her. It created a permanent rift.11

Photographs of President Lincoln mark his aged physical state by the end of the war. The stress and heartbreak he and his family endured during those four years took a great toll on him. When General Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, no one was more elated than the President, who knew the war was, at last, coming to an end – and with his much hoped for Union triumph.

On Friday, April 14, 1865, Robert Lincoln, who had served on General Grant’s staff and had waited on the McLean porch during the surrender, ate breakfast at the White House with his parents. He showed his father a carte de visite of General Lee. Lincoln spoke with his eldest son about the pursuit of a law degree, hoping Robert would follow his father’s profession. At eleven a.m., Lincoln met with General Grant and the Cabinet. Secretary John Nicolay remembered, “ I never saw Mr. Lincoln so cheerful and happy.” By lunchtime, the Lincolns learned that the Grants declined their invitation to accompany the Lincolns to the theater that evening. Other couples were invited, such as the Stantons, but they too declined. At last a young couple, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, accepted. Lincoln commented to Mary that he did not wish to go, but the public expected it of him. He then spent the afternoon in his office, issuing pardons, hearing grievances, and receiving callers. At 5 p.m. he and Mary took a carriage ride to the Navy Yard. “This day I consider the war has come to a close,” Lincoln told his wife. “We must both be more cheerful in the future.”12

Dinner was at six p.m. After dining, Lincoln went to the War Department, where he spoke with Detective Crook, one of his bodyguards, who implored the President to avoid the theater that night. Crook then offered to accompany him. “No,” Lincoln replied, “you’ve had a long, hard day’s work, and must go home.” The pair parted at the portico of the White House, where Lincoln said simply, “Goodbye, Crook,” and walked up the steps. Within the hour, he and Mary departed for Ford’s Theater, stopping to pick up their guests en route.13

That night at Ford's Theater, an assassin's bullet found its mark.

Julia Taft documented her elder brother’s memory, a doctor attending the dying President at the Peterson House in his final hours. Because so many waited in the crowded room, the air was stifling, and someone opened a window. Lilacs bloomed in luxuriant bushes outside, and the odor permeated the room where Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15. “As long as Charlie lived,” Julia wrote, “ the scent of lilacs would turn him sick and faint, as it brought back the horror of that awful night.”14

Mary Lincoln, who witnessed the assassination, was unable to cope with her dark grief. Robert too, was distraught, as was young Tad, who had recently turned twelve years old less than two weeks earlier. Without his mother or brother to comfort him, the youngest Lincoln sought solace from a White House staffer on Easter Sunday. He asked the man if he thought his father had gone to Heaven. The servant replied in the affirmative. “Then I am glad he has gone there,” Tad answered, “for he was never happy after he came here. This was not a good place for him.”15

Tad died of pleurisy in 1871 at age 19. He had fallen ill on the voyage home from Europe, after a lengthy stay there with his mother.

Mary Lincoln was devastated at the loss of her youngest son. She also lost her eldest son, albeit not to death. Robert had his mother committed to an asylum, where she spent just under four months. She never forgave him for swearing in court of her “derangement.” She traveled to Europe, spending time in France and Italy, before returning to Springfield, where she died in 1882. She considered her last years to be her “Gethsemane.”

16

Lincoln, the honest and astute lawyer, had left no will, which compounded his widow’s monetary problems, and in part led to her only surviving son’s emotional estrangement. Mary, too, left no will.

17

The Lincoln line has died out, but the memory of what one man did to preserve the Union, at a crushing cost, will never be forgotten. The government of the people still remains, ever grateful for his sacrifice, and that of his widow, and his sons.

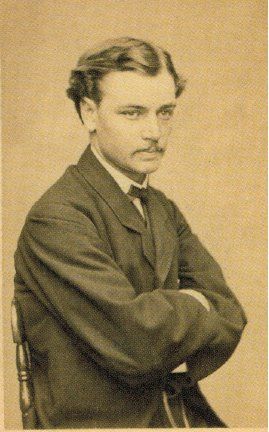

Robert Lincoln, the last surviving Lincoln son

Sources: Baker, Jean H. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography . New York: W.W. Norton Company, 2008. Bayne, Julia Taft. Tad Lincoln’s Father . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2001 (reprint, first published in The Atlantic Monthly, 1895). Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln at Home . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. Herndon, William H. & Jesse W. Weik. Herndon’s Lincoln . Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006 (reprint, first published in 1872). Lamon, Ward Hill. Recollections of Abraham Lincoln . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994 (reprint, first published in 1895). Oates, Stephen B. With Malice Toward None: A Life of Abraham Lincoln . New York: HarperCollins, 1977. Phillips, Donald T. Lincoln on Leadership for Today . Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years . New York: Galahad Books, 1993 (reprint, first published as two volumes, 1926, 1939).

End Notes:

1. Lamon, pp. 111, 32.

2. Donald, p. 69. Oates, p. 95. Lincoln had also lost a young lady friend

with whom some claim he may

have been engaged, Anne Rutledge, before he met his future

wife.

3. Baynes, pp. 70, 3, 13.

4. Herndon, pp. 257-258.

5. Baker, p. 196.

6. Ibid., p. 226.

7. Baynes, p. 78.

8. Ibid.

9. Baker, pp. 213, 218. Donald, p. 41.

10. Sandburg, p. 290.

11. Baker, p. 224.

12. Oates, pp. 427-429.

13. Ibid., p. 429.

14. Baynes, pp. 84-85.

15. Phillips, p. 277.

16. Baker, pp. 319, 336, 357.

17. Ibid., p. 369. Robert Lincoln lived until 1926, at age 83. One daughter, Jessie, married and had a son, the only Lincoln grandson, who died childless in 1985.