The Man Who Beat Hitler

by Diana Loski

General Eisenhower

(Library of Congress)

As the old veterans of World War II pass from us, and the anniversaries of their battles are kept by another generation, there are constant reminders of the vestiges of the former fields of fire. As the terrible reality of World War II fades with the passage of time, the horror of the man who caused the war also fades from memory.

It is essential that we realize and remember the evil – for that is what it was – that caused tens of millions to perish over six years of war. While one disturbed man and his cronies brought such widespread death and terrible destruction, it is equally important to remember the one man, along with his allies, who claimed a sure victory over Hitler and the Nazis. That man was Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Knowing of the humble beginnings of the future Supreme Allied Commander, one might never have guessed what this man, the third of seven boys born to two orphaned Civil War parents, was capable of accomplishing. He was a farm boy who dreamed of playing professional sports, who only applied to West Point because it would provide him with an education that his parents could not afford to give. When a sport injury made the one dream impossible, another presented itself, and Ike, as he was known, answered the call to a different duty.

The Eisenhower work ethic, taught to him as a boy, coupled with the need to learn to get along with his many brothers – and his mercurial father – instilled a skill for dealing with people that could not be taught. And he experienced plenty of disappointments along the way. While Ike yearned to go to the fight in World War I France with the other West Point graduates, he was disappointed. Instead of fighting overseas, Eisenhower was appointed as the commander of Camp Colt, a World War I training camp for tanks in Gettysburg. “I could see myself, years later, silent at class reunions while others reminisced of the battle,” he wrote. “For a man who likes to talk as much as I, that would have been intolerable punishment.” He had desperately hoped to go overseas. He did not know then that he certainly would do so, but during another war.1

From Camp Colt to Camp Meade, then serving with General Fox Conner in Panama, then as the aide to General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines, Eisenhower rose through the ranks and learned the art of leadership from some of America’s greatest commanders of the time.

At home in the United States, the populace experienced a decade of plenty followed by a decade of extreme economic depression. While Hitler, who was planning and succeeding in his rise to power, and was surreptitiously arming his nation and preparing for war, the rest of the western world never even thought of such a conflict, and so they did not prepare for it. “The American people,” Ike recalled, “in their abhorrence of war, denied themselves a reasonable military posture…the handicaps were many.”2

When America entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hitler also declared war on our nation. Ike had known since the early 1930s that World War II was an inevitable eventuality – and on December 12, 1941 he received a phone call from General George Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in Washington, D.C. The message was “to hop a plane and get up here right away.” It was actually destiny calling.3 General Eisenhower soon became the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, which included Allied Troops from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

Ike knew that the American forces were not ready to fight the Nazis. A leader who realized that emotional readiness was equally essential to physical capability, Ike prepared the legions for a true crusade.

There are numerous ways in which General Eisenhower prepared to vanquish the Nazi war machine. They included:

He knew the mistakes of the past and was determined not to fall into the same trap. Ike had been in Gettysburg for most of the time that the Americans were in France during World War I, but he knew many who had been there. He knew the hopeless tactics of trench warfare. British and French generals had hurled inexperienced troops toward the German forces – only to have them killed by the thousands. With casualties at the Somme and Verdun exceeding a million each, the volume of deaths was appalling – and for no gain whatsoever. General Eisenhower was determined that his troops would be honed and prepared before taking on the Nazis. During 1942 and 1943, many criticized the Allied forces for taking so long to invade Europe to stop the Nazis. Ike, however, knew the troops were not ready and needed training. “Behind the dunes [in France] and low cliffs the Nazis had through four years been fortifying beaches and ports,” he remembered. The Nazis had prepared against an invasion on the coast of France for four years – from Scandinavia to the Pyrenees. It was daunting to even think of the probable cost in human life in penetrating that Atlantic Wall.4

The Eisenhowers' firstborn son had succumbed at age 3 to scarlet fever in 1920. Ike and Mamie never fully recovered from it, and he refused to allow any waste of human life, for the sake of parents everywhere, as much as possible. He answered every letter of grieving parents: “During the war hundreds of brokenhearted fathers, mothers, and sweethearts wrote to me…begging for some hope that a loved one might still be alive, or at the very least, for some additional detail as to the manner of his death….I know of no more effective means of developing an undying hatred of those responsible for aggressive war than to assume the obligation of attempting to express sympathy to families bereaved by it.”5

He studied successful military leaders throughout history. Ike loved to read, and was enthralled by great leaders of the past, from Hannibal and Julius Caesar to Abraham Lincoln and Civil War generals. He appreciated Hannibal’s ability to strategize and implement method against his enemies, he noted the daring exploits of Julius Caesar carried out with aplomb – such as building a bridge across the Rhine in ten days for a victory against the Goths. Ike also recognized that Caesar showed appreciation to his men and took care of them when they were broken and injured. He saw the greatness in Abraham Lincoln’s modesty and his stance against what was wrong, even if he stood alone. As a student of the Battle of Gettysburg, Ike appreciated George Meade’s willingness to listen to subordinates, and the difficulty of his decisions that led to the Union’s turning point of the war. He understood how Robert E. Lee’s men were willing to follow him through any storm, as Lee shared in the deprivations of the enlisted men, and how Lee trusted them to make decisions on the field in his absence. General Eisenhower acquired great knowledge from the study of these past commanders. He knew he would need it. “For the sort of attack before us, we had no precedent in history,” he remarked later. “OVERLORD was at once a singular military expedition and a fearsome risk.”6

He was optimistic. “I first realized,” Ike wrote, “how inexorably and inescapably strain and tension wear away at the leader’s endurance, his judgment, and his confidence.” He knew he had to “preserve optimism…without confidence, enthusiasm and optimism in the command, victory is scarcely obtainable.” During one of Ike’s talks with Churchill about the D-Day invasion, he remembered the Prime Minister’s private concerns. “When I think of the beaches of Normandy choked with the flower of American and British youth,” Churchill said, “and when in my mind’s eye, I see the tides running red with their blood, I have my doubts…I have my doubts.”7

General Eisenhower, though, never doubted that the Allies would carry it through. He did not have a plan B for the D-Day invasion, or an escape route. The troops, who had trained for two years, simply had to get ashore and stay there. And stay they did.

He felt strongly that the cause of the Allies was the right cause. General Eisenhower’s memoir about World War II is aptly titled Crusade in Europe. That is exactly how Ike saw the fight against the Nazis – that it was a crusade. “Eisenhower believed with all his heart in the cause he was fighting for,” wrote World War II historian Stephen Ambrose. “He hated the Nazis and all they represented.” His attitude was infectious, as was his enthusiasm and positivity. He was “a living dynamo of energy” remembered one of his staff, who added that Ike had “amazing courage for the future.” Hitler may have had enthusiastic followers in the beginning of the war, as long as he was winning. But, when losses and the multitude of deaths began piling up, many in the high command – as well as enlisted men – many found their enthusiasm for der Führer waning.8

Ike got along well with others, among the Allied high command and with the enlisted men. Another stark contrast between General Eisenhower and Hitler is the way they interacted with others. Hitler demanded total obedience. Anyone who disagreed with him, from the beginning of his time as leader, usually paid dearly for their antagonism. The Night of Long Knives is one example from the summer of 1934, where Hitler killed or imprisoned all his opposition. Hitler’s megalomania was the main reason the Allies were able to penetrate the Atlantic Wall – in just one day – because he was certain the attack would come from the Pas de Calais (Ike had made sure he believed the false information about it), and was sleeping when the D-Day attack reached the shores of Normandy. His subordinates were too frightened to wake him. Ike would have never instilled such fear into his men.

From the British and American major generals to the enlisted private, Ike showed interest and approachability. He even got along with the difficult and temperamental Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the French Resistance, and Britain's vainglorious and cautious Montgomery. Ike’s office called for political prowess as well as field command – an unusual pairing that the general was able to accomplish.

One interaction that General Eisenhower mentioned during the closing weeks of the war involved crossing the massive Rhine River. Standing on the banks of the river, Ike mingled with the troops – something he often did. He noticed that one infantryman, very young, seemed silent and depressed. He asked the soldier how he was feeling. The private replied, “General…I’m awful nervous. I was wounded two months ago and just got back from the hospital yesterday. I don’t feel so good!” Ike replied, “Well, you and I are a good pair then, because I’m nervous too. But we’ve planned this attack for a long time and we’ve got all the planes, the guns, and the airborne troops we can use to smash the Germans.”9

Most generals would never stoop to speak to an enlisted man, or to sympathize with his nervousness. Hitler, especially, would not have showed any sympathy or kindness. But Ike did. His reply helped the young man, who said, “I meant I was nervous; I’m not anymore.”10

General Eisenhower, in training his general officers, admonished them to “be like fathers to their men.” He added that “their companies must be like a big family.” He felt the same way about them all. The soldiers felt that kinship, and responded overwhelmingly. One contemporary recalled, “They just loved him!”11

Eisenhower was tough, too. Once the Allies made their way into France, two intoxicated soldiers attacked a defenseless civilian woman. When a man came to her aid, they killed him. Ike ordered a military trial, followed by a swift public execution. As a result, those types of violence among the Allied troops were minimal.

He was present on the field. Ike, unlike many of his rank, spent time among the troops and near the fields of battle. He traveled extensively, to north Africa, to Italy, throughout France and into Germany. He had an office hidden in the Rock of Gibraltar, a British territory. When Hitler made a last, desperate attempt at an attack in the Ardennes Forest, known as the Battle of the Bulge, Ike was nearby at Verdun and immediately called a conference there among the high command. Surprised at Hitler’s attempt so close to Christmas – a holiday so many Germans cherished – Ike kept calm, saw where reinforcements were needed and directed the generals where to plug the lines. General Patton, who was present, fearlessly offered his Third Army to march into the fray, a move that helped turn the tide back to the Allies’ favor.12

Ike’s subordinates followed his example. When Patton’s Third Army reached Bastogne – the Belgian crossroads town that was besieged by the Nazis – Patton was right there with them.

Hitler, though, was far away in his mountain resort. When the Allies invaded Germany, Hitler hid in an underground bunker. On April 30, 1945 he committed suicide.

Ike followed through to the end. Present in Germany as the Allies drew closer to Berlin and war’s end, General Eisenhower learned about yet another Nazi atrocity. In early April, he entered a satellite camp of the infamous Buchenwald Concentration Camp, south of Berlin near Dresden. He wrote to General Marshall about it on April 15, 1945: “The things I saw beggared description…The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick.” He described fully the filth, stench, and deaths piled high in rooms and outdoors, ready for burial or burning. He described the ovens and the ghastly piles of corpses. He described how General Patton became ill and refused to go into any more rooms, but Ike went inside on purpose, “in order to be in position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely as ‘propaganda’.” He asked General Marshall to visit the area, to see it for himself. He also urged the press to see the death camp – only one of so many throughout Europe. The atrocities of the Third Reich were boundless, but General Eisenhower decidedly shone a light into the dark recesses of the Nazi regime and their revolting leader.13

He was a soldier for peace. Once the war had ended, and the Allies had prevailed, Ike knew that world peace was still vulnerable. For peace to not only prevail but to endure, the general saw that there was work ahead. For his work with the United Nations, and his two-term Presidency that followed, Ike was tireless in his quest for lasting peace. “Peace is an absolute necessity in this world,” he said in a speech at war’s end in 1945.14

He served at the head of NATO, at the request of President Truman, and traveled to Europe again as an advocate for peace. Europeans saw him as the hero that he was, and multitudes of crowds turned out to see him – and to listen to him. “I return with an unshakeable faith in Europe,” he said in one address, “in their willingness to sacrifice for a secure peace.” As President, Ike invited Russian President Nikita Khrushchev to his Gettysburg farm, realizing that the approaching Cold War could ruin any hope for a lasting camaraderie. As one of his final foreign visits as President, he traveled to eleven countries in the closing month of 1959, including nations of the Middle East, to see the people, and to celebrate peaceful relationships with those countries. He was celebrated by tens of thousands, from heads of state to crowds in the streets who waited in hordes to see him as his motorcade passed. He was loved by millions all over the world. After Ike gave a speech to the parliament in Tehran, “the members of the assembly gave him a standing ovation.” Ike experienced the same all over Europe and the Middle East. They recognized him as the man who beat the Nazis, and the legacy was everlasting.15

It has been fifty-five years since Dwight D. Eisenhower passed, and it seems that many have forgotten what he has done for the future generations. Prepared from his youth for the greatest of challenges, Ike owns a legacy that few can equal. Born on a stormy October night in 1890, and leaving on a sunny spring day in late March of 1969, he weathered the 20th century’s greatest storm of all – when one evil man managed to gain control of Europe, murdering anyone who stood in his way, determined to rule the world. That terrible man failed. While there were many thousands who sacrificed for freedom and ultimate peace, they were led by one who managed that formidable task. His name was Eisenhower.

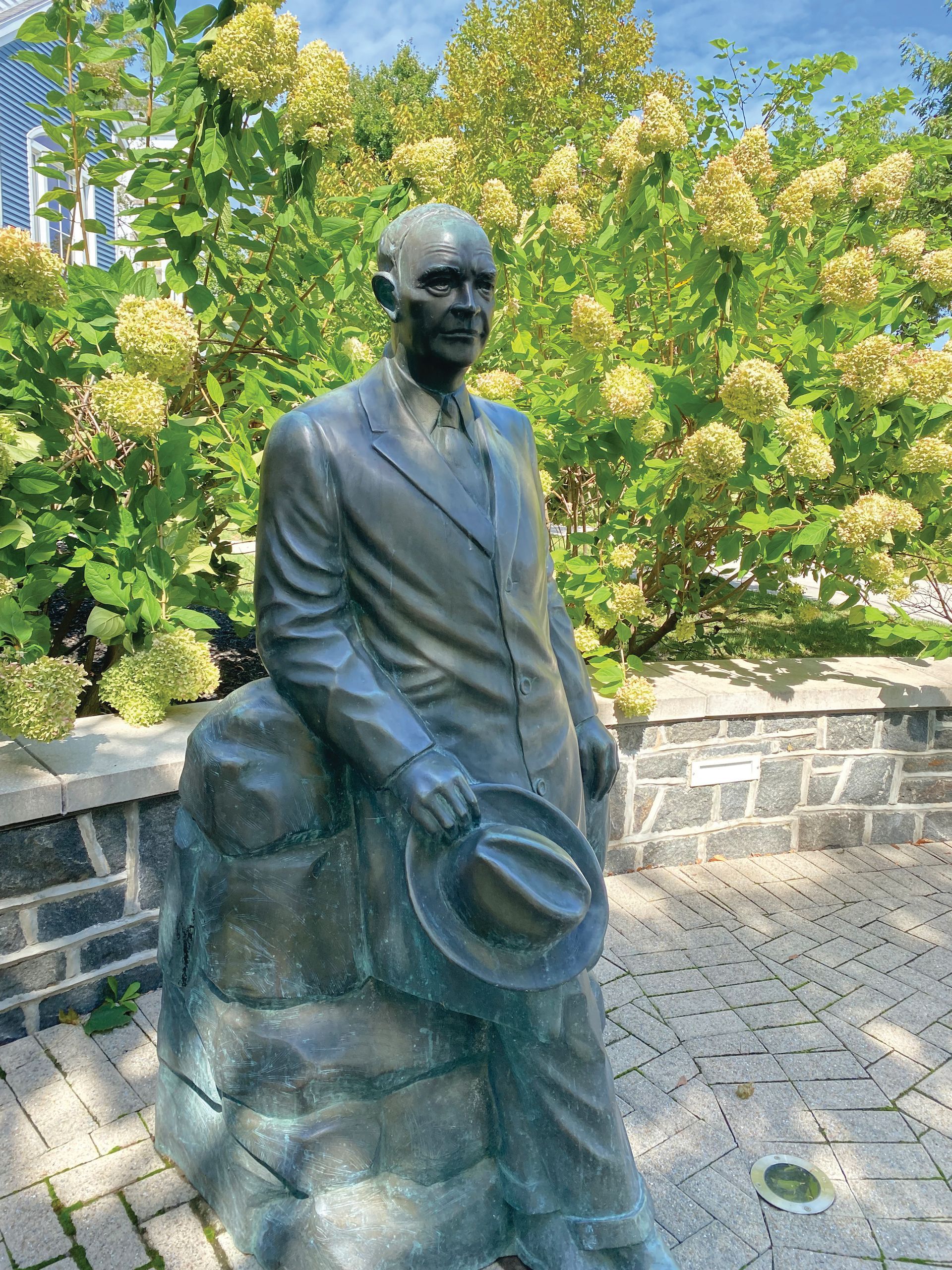

Gettysburg's Eisenhower statue as a Gettysburg resident

(Author photo)

Sources: Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994. Eisenhower, Dwight D. At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. National Park Service: Eastern Acorn Press, 1967. Eisenhower, Dwight D. Crusade in Europe. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1948. Hill, Clint. Five Presidents: My Extraordinary Journey with Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford. New York: Gallery Books, 2016. Letter, Dwight D. Eisenhower to George Marshal, April 15, 1945, echoesandreflections.org. Patton, George S. Jr., War As I Knew It. New York: Bantam Books, 1980 (reprint, first published in 1947 by Houghton Mifflin Company). Smith, Jean. Eisenhower in War and Peace. New York: Random House, 2013.

End Notes:

1. Eisenhower, At Ease, p. 136.

2. Eisenhower, Crusade, p. 7.

3. Ibid., p. 14.

4. Eisenhower, At Ease, p. 273.

5. Eisenhower, Crusade, p. 470.

6. Eisenhower, At Ease, p. 273.

7. Ambrose, p. 61. Eisenhower, At Ease, p. 273.

8. Ambrose, pp. 70, 61.

9. Eisenhower, Crusade, p. 389.

10. Ibid.

11. Ambrose, p. 135.

12. Patton, p. 364.

13. Letter, Eisenhower to Marshall, Apr. 15, 1945, echoesandreflections.org.

14. Smith, p. 573.

15. Eisenhower, At Ease, p 39

Gettysburg's Eisenhower statue, as Supreme Allied Commander

(Author photo)